Israel’s Kurt Cobain Turned Religious Doubt and Mental Illness Into Haunting Music

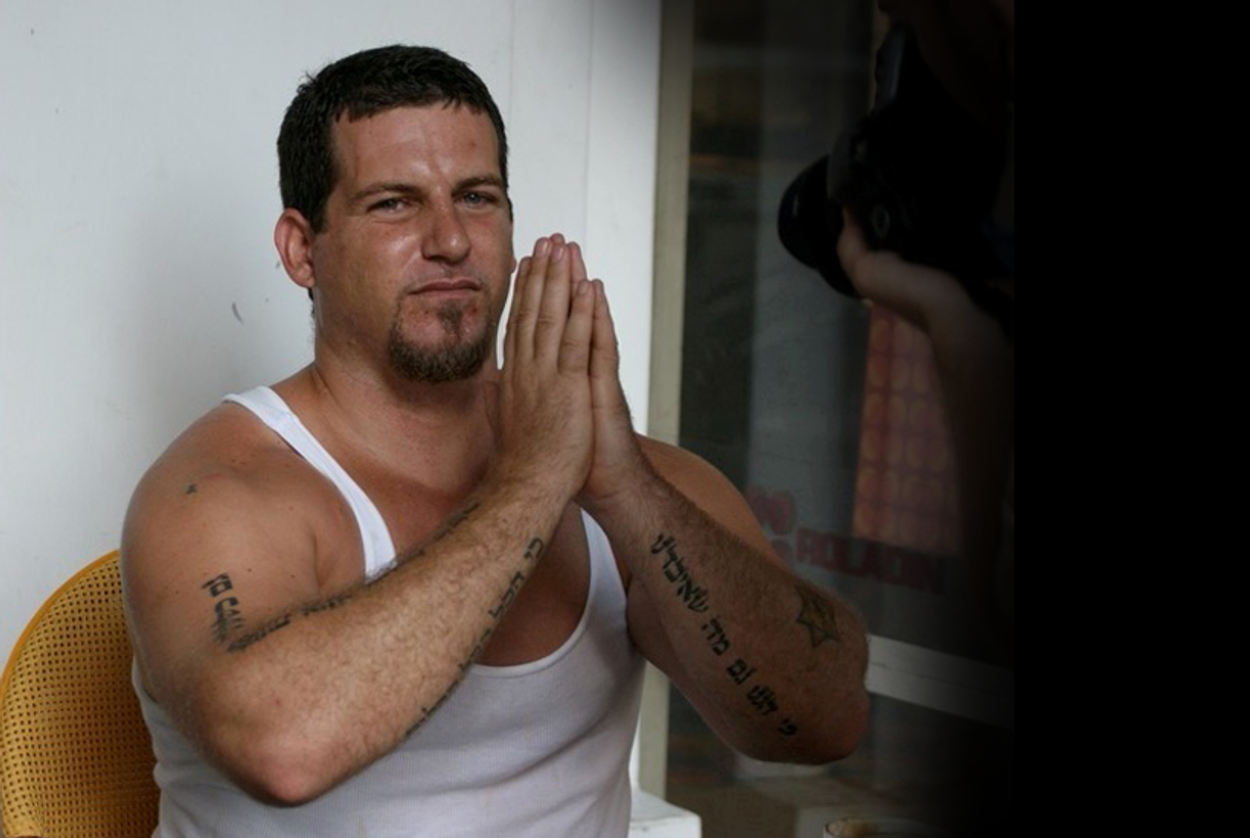

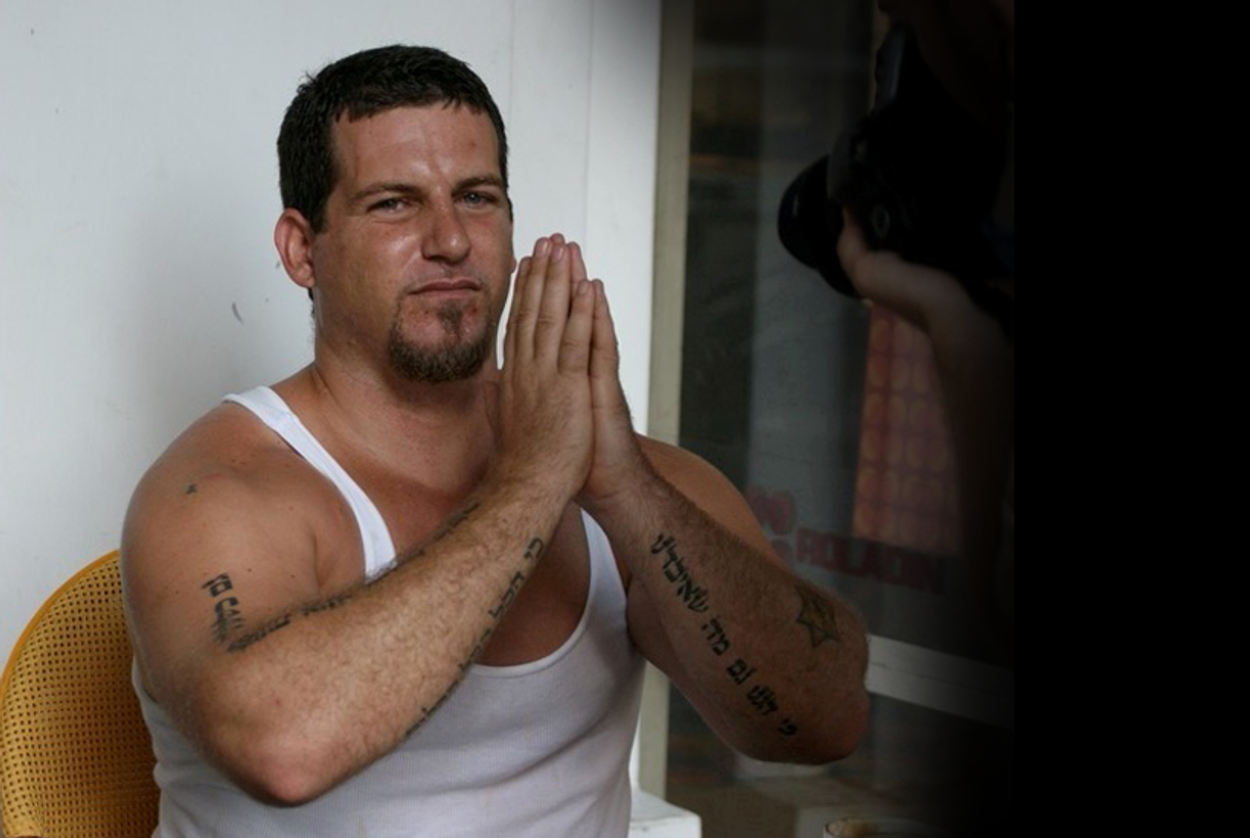

Gabriel Balachsan, found dead this week at age 37, turned a troubled interior life into powerful art

The Israeli musician Gabriel Balachsan lived in a small house in a southern moshav, or settlement, called Talmei Eliyahu. To the few journalists who cared enough about him to make the trek and meet him in person, he said that it was the desert, flat and arid, that drove him to become an artist; if anything was to bloom there in Talmei Eliyahu, a community of mostly religious North African Jews on the edge of the Negev, a stone’s throw from Gaza, he’d have to make it himself. And Balachsan’s music sounded every bit like the view from his window: It was unremitting, lashing at the listener like the early morning wind, prickly and defiant like a sun-struck shrub.

Inside Balachsan’s bedroom, however, it was a different story. The room was barely decorated, except for messages the singer had scribbled with a pencil all over the walls. Some were slivers of poetry, others bits of text messages he’d received from his many dedicated fans, transcribed onto the wall to give Balachsan, who was diagnosed in his early twenties as bipolar, something to get him through his darkest days. “Just don’t hurt anybody,” said one such scrawling, “not even yourself. Guard your soul.” But Balachsan couldn’t: This week, he was found dead in his room. His family buried him before an autopsy could be conducted. Already admired by many of his colleagues in Israel’s intimate music scene, he had turned, in the days since his death, into something grander, into a local, mystical version of Kurt Cobain, a sainted figure in which all others sought solace.

The religious allusion isn’t hyperbole: Music, more than all other art forms, has always been a conduit of spiritual ecstasy. In the ancient Temple, for example, musicians were the only ones admitted alongside the priestly class, and Augustine, describing his own process of awakening, wrote of a seminal moment in which he stepped into a church and heard a moving hymn: “The music surged in my ears,” he wrote, “truth seeped into my heart, and feelings of devotion overflowed.” Being a form of religious life, music, too, depends on its priests and even more on its martyrs; this is why dead movie stars and writers and painters are soon resigned to the history books while Jim Morrison and Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin live on as icons for the young to revere. And in Israel, no other artist, perhaps, understood his religious duties as seriously as Balachsan. His music was often described by critics as cantorial, simple stripped-down melodies carried forth by a man’s voice, teetering between speech and song, and addressing, it always seemed, not so much his listeners here on earth but some higher power in heaven.

That higher power tormented Balachsan. He was born into a secular family that became religious when he was 3 or 4 years old. And he fiercely believed in God until he didn’t; one of his strongest spiritual revelations, he said, came on the eve of Rosh Hashanah one year, when he decided, for the first time in his life, to desecrate the holy day. Waiting for the festive meal to conclude, he sneaked into his room, turned off the lights, and turned on the radio. He was expecting, he told an interviewer years later, for tongues of fire to emerge from the heavens and consume him for his sins. But none materialized, and the artist was left alone in his room to continue and grapple with his faith and his mental illness alike.

For Balachsan, it was the same struggle, the one at the core of his music. His song “Satan,” for example, begins with his take on the vidui katan, or small confession, a part of the Shacharis morning prayer in which Jews admit their sins to the Lord. Balachsan begins by reciting the prayer more or less verbatim, and then, in a furious stream of consciousness, without stopping for punctuation or breath, adds some confessions of his own: “I pretended to be enlightened I thought the same things as people I hate I watched terrible movies and enjoyed them I listened to stupid and deceitful music and found it moving and I masturbated I masturbated so much watching filthy pornos contaminated with violence I was wallowing in puddles I was running in the streets of Tel Aviv gnawed by psychosis.” As the song draws to an end, he ties together his disbelief and his mental state, portraying his illness as divine punishment for his debased life: “The devil doesn’t exist, but he’s strong enough to kill you,” he howls. “He will bury you alive and leave you in a deep hole with only a thin slit for your lips and you’ll breathe some thin air and then he’ll piss into your mouth all that he’s accumulated in his filthy bladder for years.”

Lines like that made Balachsan sound like the feverish love child of Jonathan Edwards and Charles Bukowski, part mad preacher and part poet of the gutters. But despite its primordial ingredients, Balachsan’s sensibility was very much of the moment. Writing in 1999 about Cobain, then already five years dead, Greil Marcus noted that Nirvana’s music was so powerful because it was “a drama with costumes but not masks.” Listening to the band’s songs, “you hear all that is lucid, simple, and unrushed—a between-past-and-future suspension of time lovely enough to convince you that the world itself has paused to listen—pulling against the desperation and hurry of everything else in the performance, and everything else that finally sucks up those brief prophecies of clarity and wipes them out.” The same was true of Balachsan’s music: It was lovely and arresting but designed, like the artist himself, to ultimately succumb.

Balachsan applied the same attitude to everything else in his life: When he had to leave his popular band, Algiers, in the late 1990s and admit himself to a psychiatric hospital, Balachsan refused to accept the common euphemisms used to discuss his condition. He insisted on being called mentally ill and spoke of the psychological and physical torments of his illness with candor in his first solo album.

This week, after the news arrived that EMTs had rushed to Balachsan’s home, to his room with the inspirational inscriptions, and spent three hours in a futile attempt to resuscitate him, his fans and his peers turned back to that first album, to one song in particular. Called “Talmei Eliyahu,” it consists mainly of Balachsan imagining his own funeral.

“And then, when the day comes, they’ll take you with them,” he sings. “They’ll eulogize you quietly, and you’ll be moved and the tears will wet the earth. Ten hunchbacked elderly men will cover you with dirt. And you’ll lie there underneath, the red dirt falling on your stomach. And then four little angels will come and take you with them, all the way up, holding your soul inside a golden box, gently, so that you don’t fall down.”

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Liel Leibovitz is a senior writer for Tablet Magazine and a host of the Unorthodox podcast.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.