The Inner Life of Gender

Can old, dead, gay, white French males save us from the West’s latest moral crusade?

A colleague and friend of mine, a Jewish lesbian who has found herself, mostly with pleasant bemusement, teaching at a small Christian university in the Midwest, recently shared with me, outraged, her employer’s new policy on “gender” and pronouns. In the solemn, moralizing tone of a land-acknowledgement—a register of piety that the school’s administrators no longer use to talk about their institution’s religious denomination—officials declared that they understood gender to be an essential component of students’ “identities.” Students have genders, and those genders must be recognized by faculty through the use of proper pronouns, on pain of administrative sanction. Gender is a vital psychic reality and a site of fraught self-investigation; it is, at the same time, a datum to be tracked and enforced by the university bureaucracy. It can, moreover, be changed at any moment, by a student’s declaration of a new gender, which will in turn be registered by administrators and recognized by faculty who want to keep their jobs.

The meaning of the terms around which the above paragraph is organized—gender, identity, recognition—have in recent years become self-evident both in the operations of policy and in people’s everyday experience of themselves. Individuals who would be suspicious of the invisible forces around which vanished moral-political orders were built (soul, destiny, telos, Providence, etc.), and who would be baffled by the various concepts by which their ancestors made sense of their selves (chastity, honor, virtue, authenticity), seem to find in gender and its related keywords a means both of expressing their inner life and of remaking the world. The apparently irrefutable obviousness of these concepts conceals from us both their novelty and their strange, self-contradictory logic.

How is it that gender could be something I have, do, understand, declare, register, recognize, and change? Gender has the pathos of a struggle to access the hidden depths of inner life, a quest for the truth of the self that centuries of Christian confession and post-Christian therapy have taught Westerners to regard as sublimely difficult and noble. But gender is also as easy, as public, and as increasingly compulsory as “saying one’s pronouns.” In what may be the basic bait-and-switch of contemporary liberalism, gender promises us a domain of personal freedom in which we can create ourselves anew and then compels us to expose that intimate self, enrolling it in a public campaign of good against evil, future against past.

Asking questions about gender reveals its status as ideology—as the transformation of a particular, contingent interpretation of the world into an ostensibly natural fact about the world. In critiquing “gender ideology,” however, one risks becoming the proponent of a counterideology no less shrilly political in its insistent defense of “common sense.” How can we resist an ideology, not least by exposing it as an ideology, without ourselves becoming ideological? How can we question “gender” without thereby becoming “fascists,” as gender theorists like Judith Butler insist we are? Is it possible to be neutral about gender—to elude the demands that its proponents place on us rather than silently accepting or screamingly refusing them?

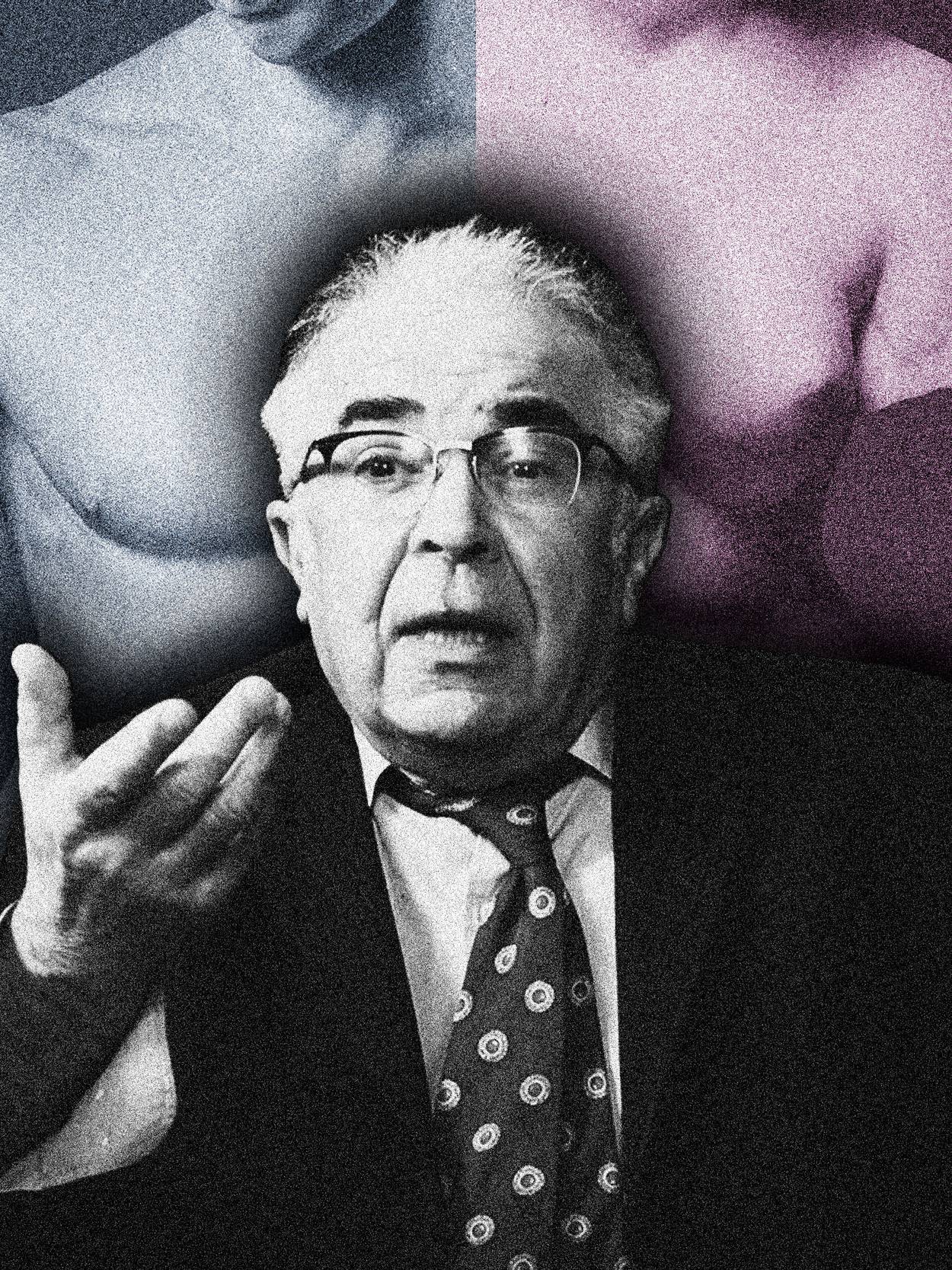

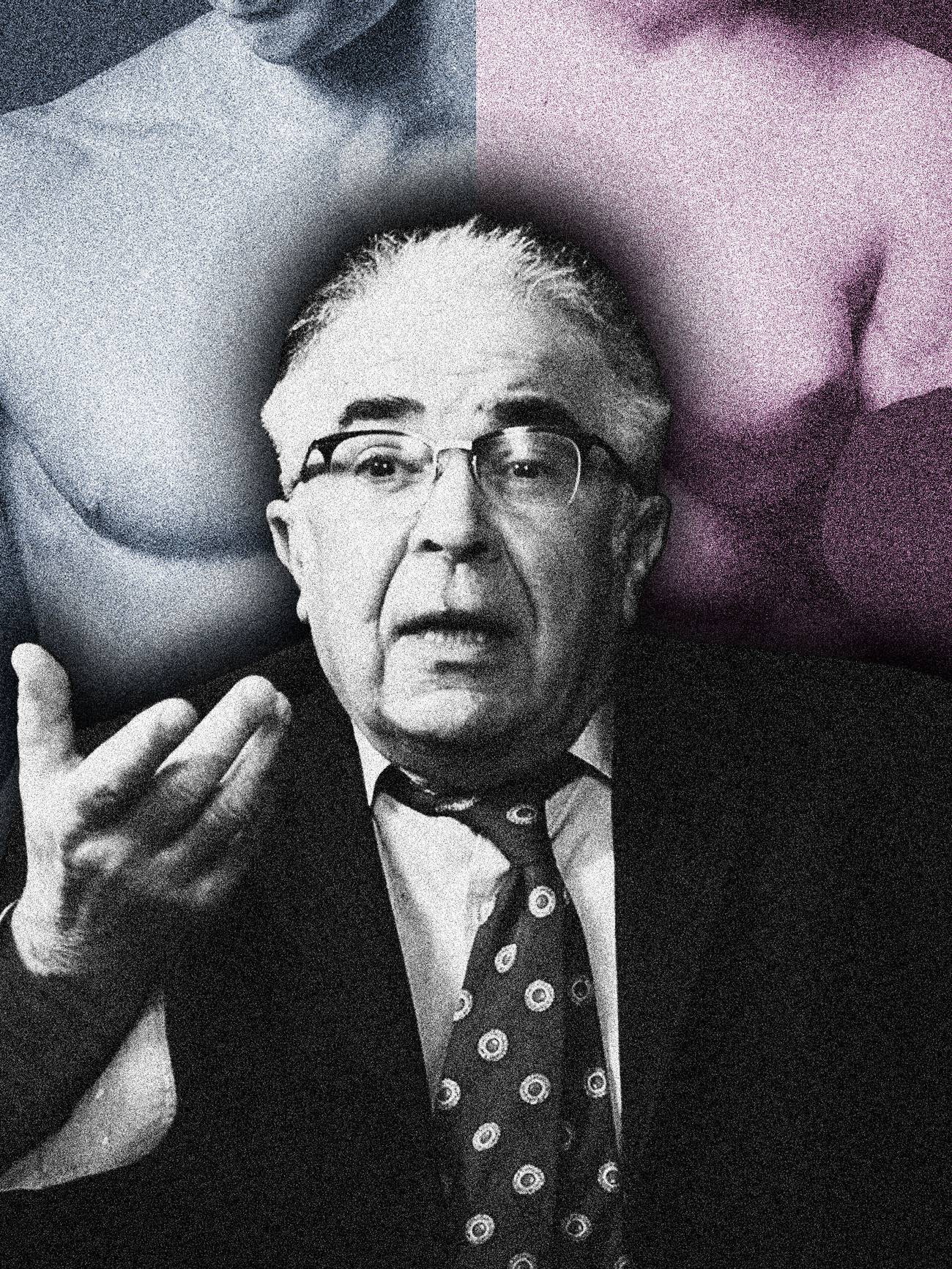

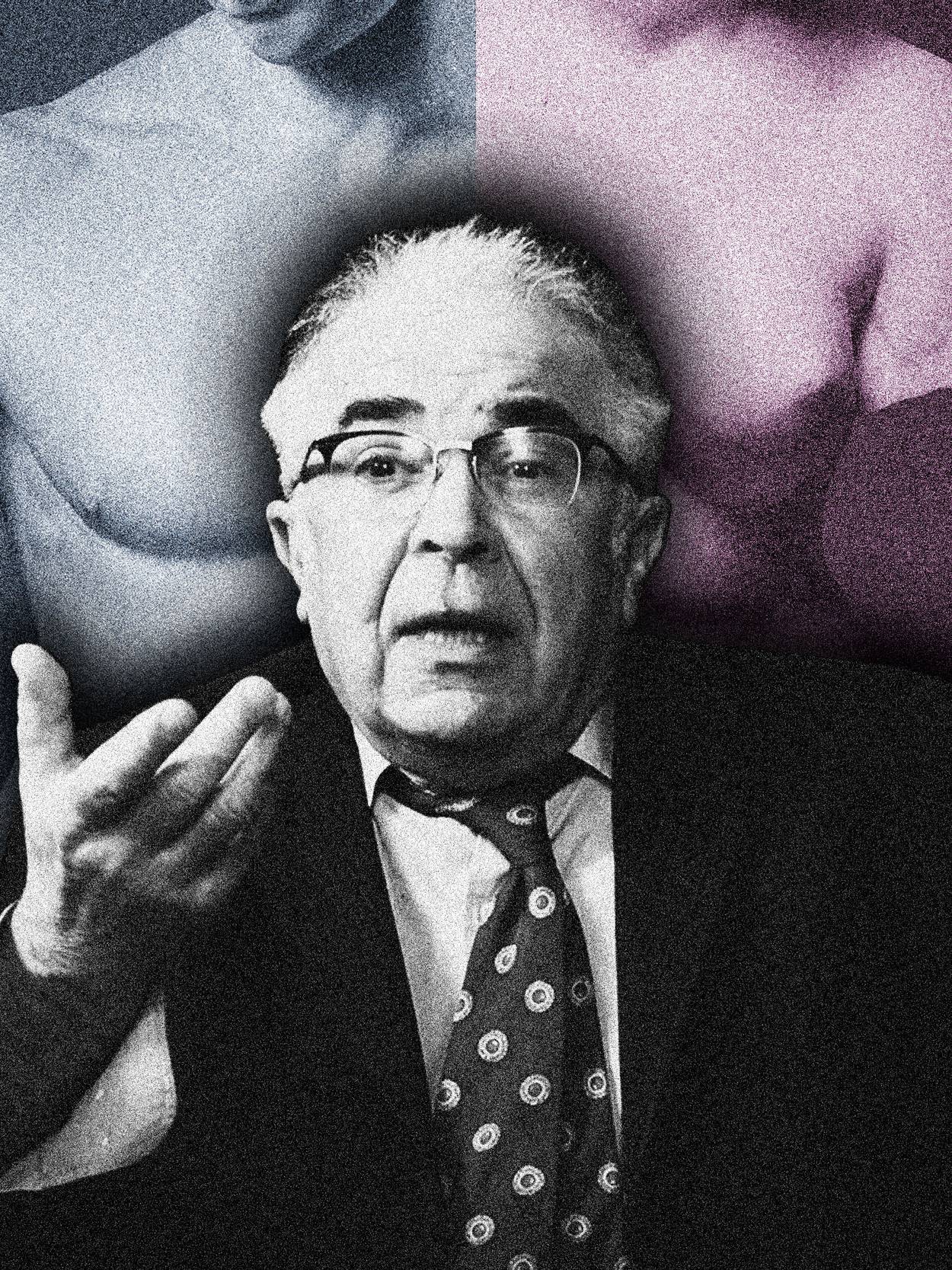

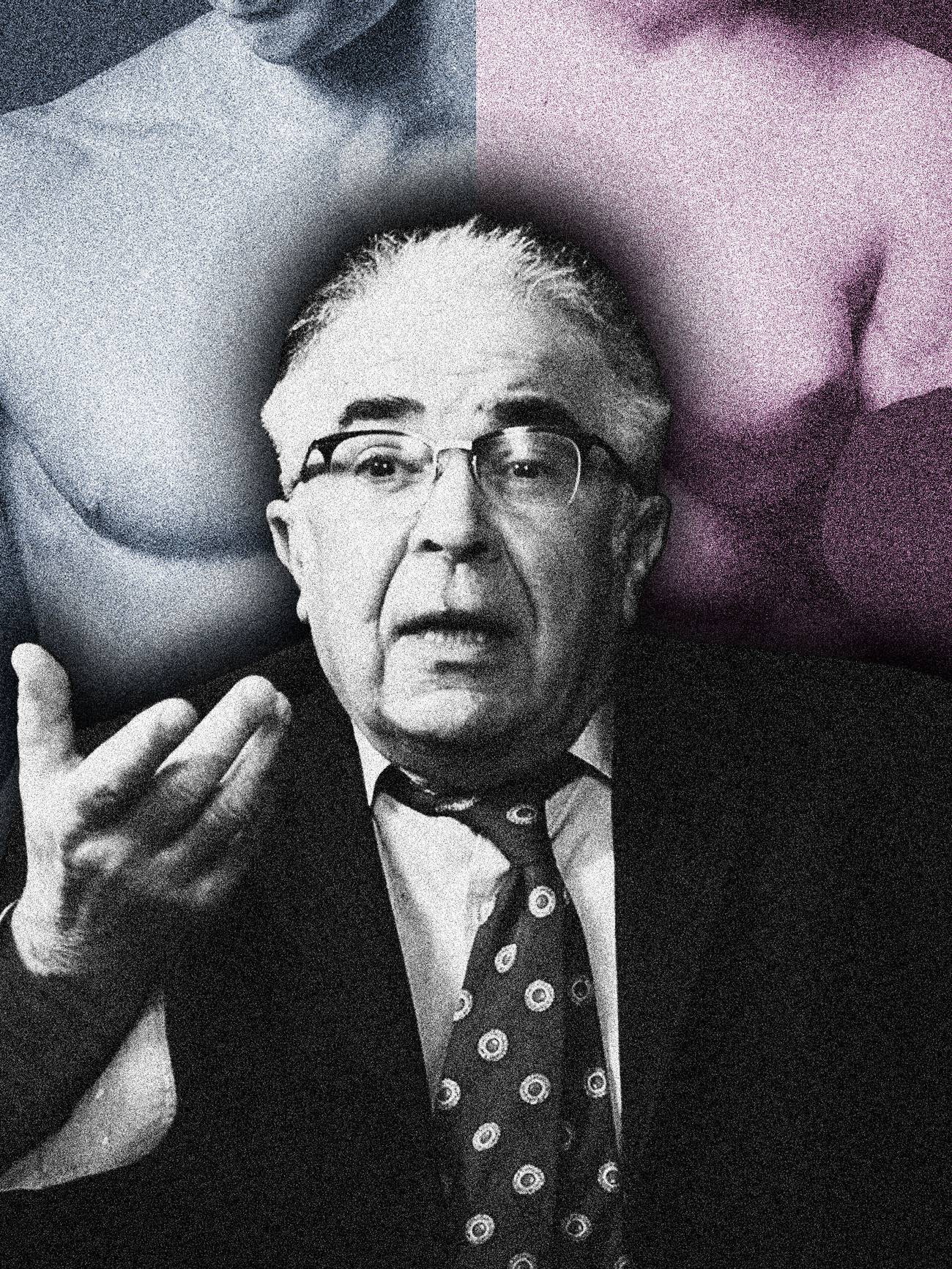

Such a sweep of Butlerian rhetorical questions suggests that the answer is “no.” But in a difficult, frustrating, and important recent book, Le sexe de Modernes: Pensée du Neutre et théorie du Genre (The Moderns’ Sex: Neutral Thought and Gender Theory, 2021), the French literary theorist Eric Marty attempts to find his way to a “yes.” His method is to apply the ideas of his teacher, Roland Barthes, to a painstaking—and convoluted—critique of “gender ideology.”

Gender originally appeared, Marty notes, in the last decades of the 20th century, as a “conceptual and abstract … epistemological tool” by which thinkers could distinguish between the supposedly natural and cultural dimensions of being a man, woman, or something other or in-between. Sex, in this original distinction, referred to the natural, physical features of our bodies; gender to the ever-shifting meanings we ascribe to sex. This very operation of distinguishing nature from culture, sex from gender, is itself, as Marty notes, one of those falsely binarizing exercises that characterize our culture—and indeed contemporary theorists of gender have abandoned the idea that there is such a thing as a “biological sex” to be held separate from our interpretations and categorizations. First distinguished from, and now superceding, the idea of sex, gender has become “a new universal evidence,” something that people experience about themselves—one of those phenomena like demonic possession or ennui that, in a given historical moment, strike contemporaries as immediately present psychological realities.

Exploring how gender has become self-evident would require an ethnographic account of the many practices by which parents, schools, psychologists, media, etc., incite individuals to find and express “gender”—an effort beyond the scope of Marty’s book. What he attempts, rather, is to show how the concept of gender became available in our recent intellectual history, such that it could be incorporated into the psychic life of the multitude. This history, to his horror, is one in which a set of thinkers whose work is taken together to constitute “French theory” or “postmodernism”—Jacques Lacan, Michel Foucault, Jacques Derrida, Roland Barthes, etc.—were so misread by their American disciples that their ideas, meant to set limits to Western civilization’s obsessive drive to posit binaries around which conflict could be stoked, have themselves become the message of a new moral-political crusade.

In what at times becomes a self-defeating irony, Marty hates America with all the obscene glee of an aging French academic. Toward the end of his book, for example, he describes the ideal society of Butler and other proponents of gender as the right of a transgender person “to freely enter a McDonald’s, which is to say, for an old-fashioned European intellectual, Hell.” He seems to take it for granted that Americans, being idiots, couldn’t possibly have understood what French thinkers were on about. Such anti-Americanism might be a useful populist bulwark against “le wokisme,” but it is not a platform for serious thinking. Worse, by enacting a polemical binary between Europe (the continent of ideas) and America (where ideas become university training modules and political bumper stickers), Marty performs the very maneuver that, following Barthes, he sees as the essence of our civilizational sickness. His division “America-Europe” is as wearisome as older binaries like “male-female” and newer ones like “cis-trans.”

We may bemoan the vicious intensity of our current culture wars, and yearn either to return to a supposedly harmonious tradition or leap forward into a utopian future—but it is our very tradition that has taught us to think in fatal binarisms and persecute each other for the sake of a new world. At least since the beginning of Christianity, whose founder announced he had come to set “brother against brother” with a message of universal love, Western thinkers have envisioned human unity as an end to be achieved through division, violence, and the annihilation of enemies. Modern prophets like Karl Marx or Ibram X. Kendi offer a secular version of the story but retain the moral: “You are either with us or against us.” Culture war is our culture.

In the years before his death in 1980, this was how Marty’s mentor Roland Barthes, the French literary critic and—in a turn few have yet appreciated—political philosopher, saw our situation. Over the preceding three decades, Barthes had approached, then abandoned, the Marxist vision of an either-or struggle between the coming revolution and its reactionary foes. By the late 1970s, he had broken both with the French Communist Party and with younger far-left radicals like the circle around the avant-garde magazine Tel Quel, with whom he traveled to Mao’s China in the last days of the Cultural Revolution. The various lefts inspired by Marxism had all been failures, it appeared; and Barthes, whose homosexuality was an open secret in French intellectual circles, was equally skeptical about the emerging post-Marxist cultural left and its sexual revolution.

In late works such as his Fragments of a Lover’s Discourse (1976), Barthes worried that, with the horizon of social and economic transformation disappearing as the disaster of the Marxist experiment became undeniable to all but the most committed ideologues, “sex” and “sexuality” would become new sites of political struggle. “Sexual liberation” would mean, he feared, not the easing of restrictions and guilt around sex, but the creation of new, polemical intensities dividing those for and against another utopia. He shared this fear with his onetime friend Michel Foucault, whose History of Sexuality, Part One critiques the new left’s struggle against “sexual repression” as just another manifestation of our centurieslong obsession with purifying ourselves and the world of invisible obstacles, without which we would, at last, be happy and good.

Marty argues that Barthes’ fears were prescient—and that his thinking offers resources for resisting what he calls, in the book’s opening line, “the latest great ideological message issued from the West,” our newest “good news” that sows division: the “gospel” of gender. While the moment of sexual liberation has passed—young people are in fact having unprecedently low amounts of sex—still newer frontiers of struggle have been opened. Now what is to be liberated from the supposedly repressive forces of convention and history is not a primal “sex” in all its polymorphous diversity, but the discernment, declaration, and documentation of something called “gender.”

In the years before his death (hit by a truck) in 1980, Barthes laid the groundwork for an alternative to such campaigns of liberation—a moral and political stance that he referred to in one interview as a “second liberalism.” Like conventional liberalism, his approach was meant to provide relief from otherwise insuperable conflicts over values, to solve the problem of how people who disagree about religion, the good life, sexual ethics, etc., can live together in relative peace. Liberalism as we know it frames these disagreements as less important than our common humanity, in light of which we each possess the same set of universal human rights, which are to be respected by public institutions we call “neutral” insofar as they take no notice of our religious, sexual, and other sorts of potentially divisive commitments.

Suspicious of the idea that rights and institutions could permanently stand outside of the arena of conflict over values, Barthes argued that tolerance would have to be based not on the neutralization of our common life, but on a suppler ethic he called “the neutral,” a repertoire of practices and attitudes for suspending conflict. From the beginning, as Marty elucidates, the idea of the neutral was connected to the possibility of what we might call the “gender-neutral,” some position where sexual difference does not apply or can, at least, be deferred from its ordinary, automatic operations of making everyone we see appear as male or female. Marty, drawing on a range of thinkers with whom Barthes was in dialogue, constructs what he calls “neutral thought,” a way of understanding “French theory” in terms of its attempt to subvert what Barthes took to be the two intertwined logics that governed our culture: polemical conflict and sexual difference.

“Subvert” here does not mean to attack, undo, or replace with a new logic—to attempt to do so would be only another form of conflict, and a new kind of sexual difference (in which we replace, as we are increasingly doing, the male-female binary with multiplying binaries like cis-trans, queer-normative, or, simply, retrograde and progressive, hateful and decent). Rather it means to find ways of making binaries, and our resistance to them, a bit more capacious and livable. Marty tracks two different approaches to “neutral thought” that both appear in Barthes, and are embodied in starker clarity in the work of two of his interlocutors: Lacan and Foucault.

For Lacan, sexual difference is not, primarily, a bodily phenomenon. It is a fundamental, inalterable aspect of the structure of language that governs our unconscious. In that sense, it is futile to hope for the abolition of sexual difference, or a world without men and women. However, the psychic structure of sexual difference can be lived and played out in many ways; all sorts of fantastic identifications are possible precisely because none of us, in our own bodily and mental realities, ever quite coincides with the positions “male” and “female” that have been assigned to us. We are all a bit perverse, in some way verging away from the polarity of “our sex.” A Lacanian tradition in American queer theory that includes Joseph Litvak, Lee Edelman and Leo Bersani has drawn on these insights to create a quietist, apolitical approach to sexual difference—one that more radical thinkers and activists have consistently opposed as a reactionary “white male” (read: Jewish) stance.

In contrast to Lacan’s vision, founded on a “law” of sexual difference that can be ludically perverted but not overturned, Foucault, a generation younger, insisted that our psyches are dominated not by transcendental and unchanging structures but by historically variable “norms.” This shift from “law” to “norm,” Marty argues, prepared the ground for today’s gender ideology. Once it could be imagined that what held in place the social and cognitive division of humanity into men and women was not a timeless principle inherent to the psyche, but a set of contingent rules (like, Foucault argued in his early work, those dividing the sane and mad), it could seem possible that those rules might be rewritten through political action.

By invoking “law,” Lacan was able to distinguish, on theoretical grounds, between, on the one hand, his shocking ideas and apparent licensing of all manner of perversity, and, on the other, an almost reactionary respect for the traditional patriarchal order. Foucault’s critique of the very idea of law, however, would seem to eliminate the possibility for such a pragmatic reconciliation between personal antinomianism and social authority. If everything about ourselves has been determined by contingent social norms that are themselves the effect of unequal power relations, it could seem that all these norms must go, that we should wage unlimited struggle against every identity that has been imposed upon us.

This is, Marty laments, where gender ideology—and specifically Judith Butler—has taken us, following a misguided appropriation of Foucault’s critique. Marty insists that Foucault, in his later writings in the 1970s and early ’80s, echoed Barthes, arguing that the point of exposing the contingency of norms was not to open them all up as sites of resistance in a global campaign of liberation, but rather to inhabit them open in order to try out, in specific, private domains, new ways of being oneself. In his readings of Foucault’s writings on gay male identity, like “Friendship as a Way of Life” (1981), Marty shows how Foucault, like Barthes, came to conceive of male homosexuality—but also, by extension, any identity—as a kind of “similarness” in which individuals playfully create shifting senses of sameness and difference that defy any understanding of self-identification as a straightforward, uncomplicated fitting of oneself into the “right” category.

Thus for example, among gay men, even two members of a couple who look so similar they appear as “boyfriend twins” will try out, and eroticize, interpretations of difference (you’re the top, I’m the bottom; you’re the funny one, I’m the smart one; you make dinner, I do the dishes). In what Barthes called “idiorhythm,” a way of being in sync with the other person apart from the world, couples and communities live out fantasies of sameness while constantly enriching and reworking them with what we need a nicer term for than “the narcissism of minor differences.” Indeed, although charges of “narcissism” and “ethnonarcissism” attend overt displays of enjoyment of belonging to a group, such pleasure is not the ecstatic recognition of one’s own self in others, but a constantly shifting process of finding likenesses and differences among one’s own group.

Think for example of the classic Jewish joke about the man who is rescued after being stranded for years on a deserted island. His rescuers find two structures and ask him what they are. “That one is my synagogue,” he answers, “and the other one, I never go to!” We could read the joke as a lesson about how all identities are based on polemical exclusions and enmities, aimed even at imaginary foes. But crucially, the man builds not a church or antisemitic league meeting hall, but rather a synagogue—he is not so much keeping the imaginary other out as beseeching his witness. He cannot be the right kind of Jew without the presence of another, different but essentially similar Jew. An identity, a community, is not the site where distinctions melt away in solidarity but the arena in which they appear—one in which we struggle to convince our peers that we individually are doing the better version of whatever it is we are all doing together.

What is it about our material conditions and emotional circuitry that is so precarious that we can no longer build the synagogue we never go to?

In this perspective, homosexuality, Jewishness, etc., appear in much the same way that Lacan, in Marty’s telling, conceived of sexual difference: as crucial elements of a life, and as elements not easily dislodged from a broader culture, but also as sufficiently indeterminate or flexible to permit all sorts of enthusiastically perverse “bad Jews” and “bad gays” to make their particular ways in the world. Foucault’s shift from “law” to “norms” allows for the possibility of historical novelties, like the distinctly modern form of romantic love between adult men, but, like Lacan’s formulation, it is tempered by a kind of conservatism, an attachment, neither ironic nor skeptical, to the contingent identity, neither freely chosen nor arbitrarily assigned, but arising out of longings and resemblances linking one to parents, teachers, lovers, and friends.

But for this sort of different-sameness to have any appeal, one must, Marty might have noted, enjoy being oneself and among one’s own! While he devotes many passages of the book to lamenting that today’s gender activists have lost the moderating element found in Foucault, turning his tactical critique of Lacanian law into a crusading mission to rewrite our norms of gender, Marty has little explanation for why people in both the U.S. and Europe find themselves unable to experience their identities playfully and privately. If we have become so earnest and indeed militant about identity, it is, as his own explanation of postmodernism shows, a problem not so much of intellectual as of social history, of the application rather than the genesis of ideas. Or, perhaps, a problem for the history of emotions, to explain the patterns of our everyday life that make contemporary subjects so insecure that they must see their particular ways of being themselves not as enjoyable private variations on public standards, or as bravura performances for a select audience, but as a demand for attention and validation from the public at large. What is it about our material conditions and emotional circuitry that is so precarious that we can no longer build the synagogue we never go to?

Marty concludes his book, despairingly, with a sweeping condemnation of gender ideology and transgenderism as the first step in a post-human apocalypse—a perspective that appeals equally to conservative TERFS and academic trans theorists. Here, as with his inveterate anti-Americanism, he seems unable to find within the resources of “neutral thought”—the “second liberalism” of Barthes; the privately radical and publicly conservative structuralism of Lacan; the semi-ironic celebration of communitarian “sameness” of Foucault—a means to suspend his anger at the state of the world.

The task for liberals—however many remain—facing the demands of gender ideology is to discover whether these resources, or any others, can help us do otherwise. The task, no less, is to elucidate how gender, as ideology, responds to and disguises the effective sources of a legitimate and widespread suffering in our society. The happy perversity postmodern liberals celebrate can exist only in a set of relatively comfortable and equitable economic and cultural conditions that, half a century ago, may have seemed to have become part of the enduring patrimony of Western democracies, but which have in the meantime been hollowed out. Resistance to gender ideology can avoid being ideological—as Marty in his fulminating anti-Americanism at times becomes—by remembering what ideology hides.

Blake Smith, a contributing writer at Tablet, lives in Chicago.