Down With George Washington!

WPA artist Victor Arnautoff’s murals get the woke treatment in San Francisco

Some of the dust has settled and some of the air has cleared, but three months after they surfaced with a bang, the volatile issues raised by Victor Arnautoff’s murals—and by his defenders and critics—have not subsided. If anything they have become more deeply entrenched with no resolution in sight. In its latest iteration, the conflict—which has a long history—came to a head on July 3, 2019, when the San Francisco school board voted unanimously to destroy the murals titled “The Life of George Washington.”

A month later, in response to widespread public outcry, the board voted 4-3 to cover the murals with panels and thereby protect students from images deemed harmful by some and historically relevant by others. Still, there’s no covering up the issues that have roiled the city and beyond.

Arnautoff’s work reminded me of Hermann Göring, who is often quoted as saying, “Whenever I hear the word culture, I reach for my revolver.” No one has reached for a revolver or fired a gun at the high school, but the city is deeply and acrimoniously divided about the meaning and significance of the WPA murals at George Washington High School, about the role of art and about the representation of Indians and African Americans.

The San Francisco Art Institute is hosting a panel discussion titled “Whose Public Art?” on Oct. 22 that will focus on the murals. It’s free and open to the public, though registration is required. Perhaps the panel, which is made up of artists and art teachers, will help illuminate the issues and quiet some of the more strident political voices. But that might be wishful thinking. The institution Living New Deal hosts a benefit party to preserve the Washington murals at a North Beach bar on Oct. 17, and in November citizens will be able to vote for or against the murals.

The divisions around the murals are signs of the erosion of social cohesion in a city that is increasingly white and wealthy. The teachers union—the United Educators of San Francisco (UESF)—is not united about the murals. While some teachers love them and want to preserve it, others feel they have to go even if that means vandalizing them by throwing paint on them. UESF has declined to take a stand on the murals, which doesn’t help matters. What are unions for if not to take courageous and sometimes unpopular stands?

San Francisco Unified School Board District President Stevon Cook led the charge against the murals. “The overwhelming majority of the people in favor of keeping the mural are older whites, while those in favor of taking it down are young people of color,” Cook wrote in an article published in The San Francisco Examiner titled, with irony, “Keep Those Slaves on that Wall!”

He added, “The people fighting to keep the mural consider themselves defenders of art and preservers of ‘true’ American history, while those opposed consider themselves the defenders of the historically oppressed.” As an African American who grew up in San Francisco, Cook argues that his ancestors gave “as much if not more, to America than any founding father. They are the true heroes of the American story.”

But Cook doesn’t tell the whole truth. While many young blacks abhor the murals, many older blacks, including author Alice Walker and actor Danny Glover defend them.

A graduate of George Washington High School, Glover said, “I view Arnautoff’s murals, as they were for me, a reminder of the horrors of human bondage and the mistreatment of native peoples, even by the father of our country.” He added, “To destroy them or block them from view would be akin to book burning.” One older black woman interviewed on KCBS’s TV show This Morning said, “It’s a new day. People no longer want to tolerate these vestiges.”

If the clash surrounding the murals is in part generational, it’s also in part cultural. One culture is that of the New Deal and the lefty 1930s that tended to celebrate working men—employed or unemployed, rural or urban—and that also memorialized the heroic American people and the American past in film, literature, and the arts. The second culture is that of the 1960s and its liberation movements, along with Black Power, that valorized the resistance to slavery, genocide, and patriarchy and called for people of color to create counterinstitutions and counterimages.

Whether San Francisco stands with Cook or goes against him, and how the conflicts are resolved, will have a lot to say about the same and similar issues surrounding the representation of race, class, and ethnicity in the United States.

***

For the time being, censorship has won. Except for students, faculty, and administrators, no one gets into the school. I only had a peek because the security guard held the door open for me and allowed me to see as much as I could see from the entrance. But the murals are online and anyone can see them there. The security guard told me, “It’s history. History sucks. You can’t cover it up.”

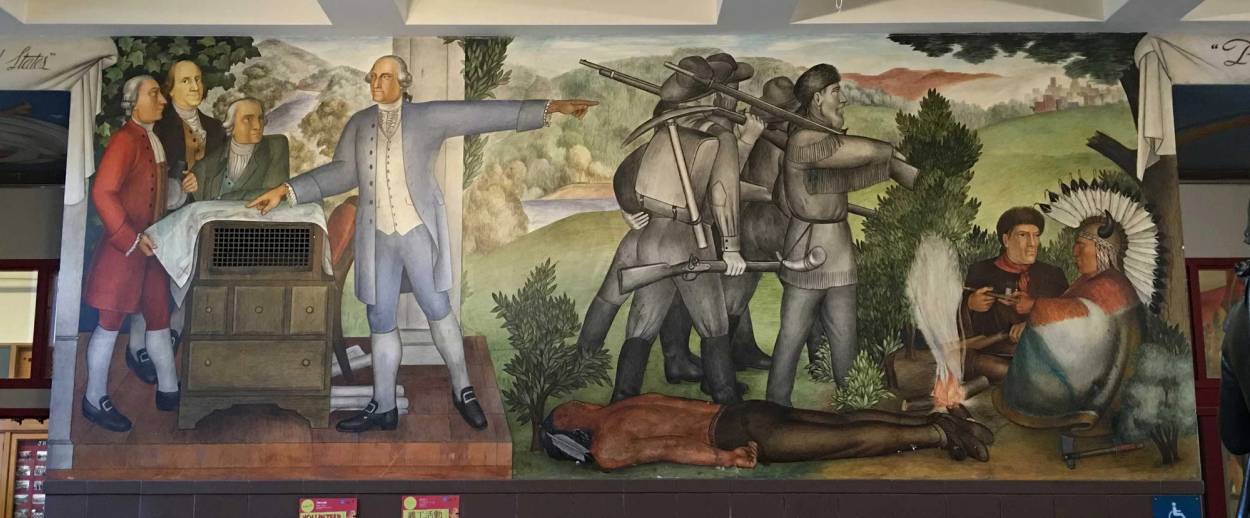

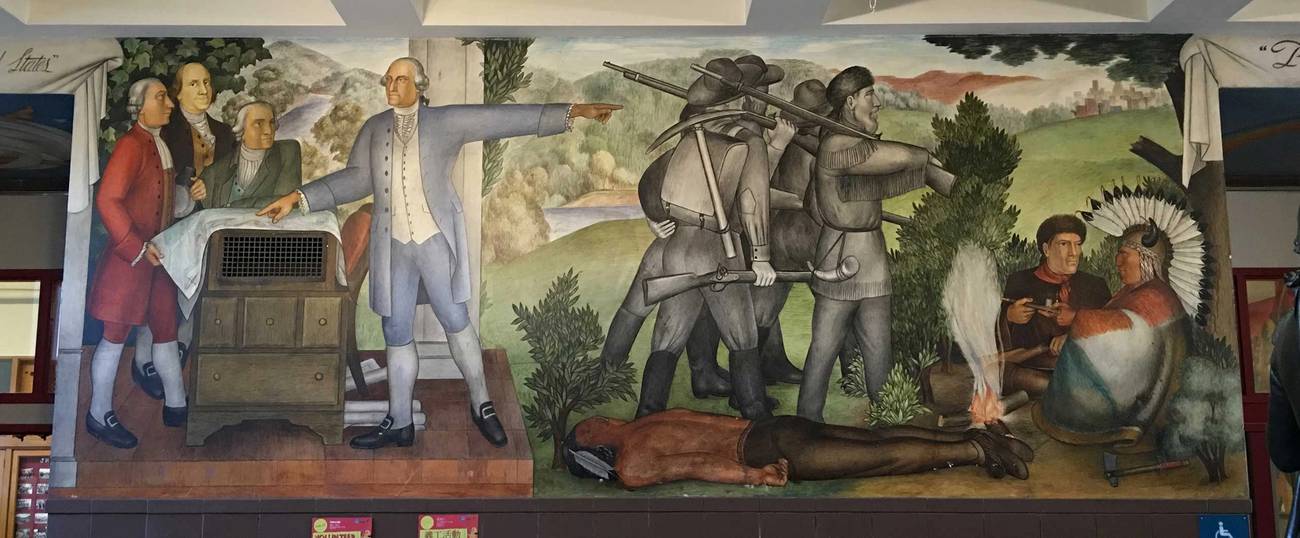

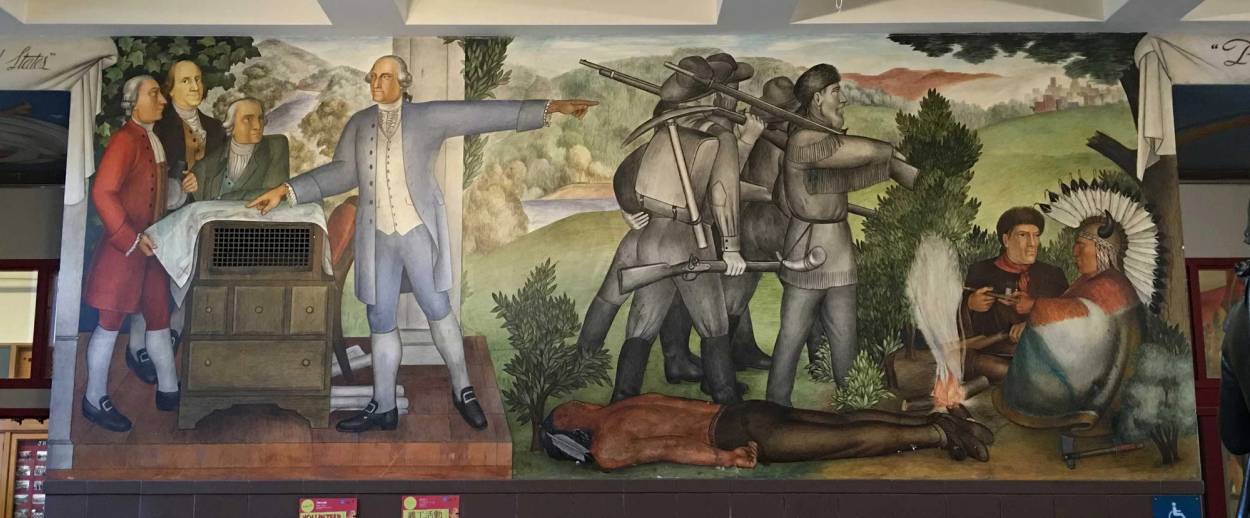

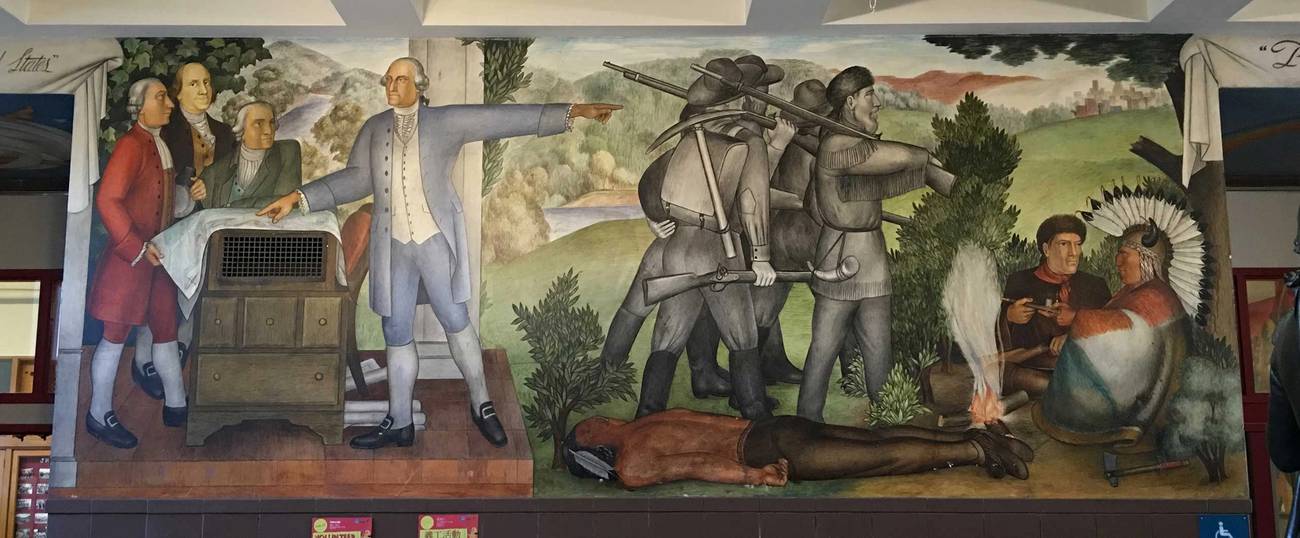

At George Washington High School the flashpoints are an image of an Indian lying face down on the ground, and another image of African Americans doing the kind of work that slaves did in Washington’s day. Some read the images as a gentle rebuke of Manifest Destiny and slavery. Others read them as acquiescence in the face of atrocities and inhumanity. Hermann Göring might have argued that Arnautoff’s work is in keeping with Nazi ideology. It depicts a strong white man and black and red men under his authority. When former San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown was asked if the murals depicted subservient African Americans, he said, “That’s the way America was.”

School board President Cook compared defenders of the murals to defenders of Confederate monuments. The pro-mural forces have argued that destroying or whitewashing Arnautoff’s work would be tantamount to lynching. There doesn’t seem to be any middle ground.

The ruckus has given birth to the “Coalition to Protest Public Art” and to denunciations of censorship in the San Francisco Chronicle and in The New York Review of Books where Michele H. Bogart argued that the murals are truly exceptional in the history of art in the United States. “For a Communist artist to get away with critiquing, as part of a federal cultural program, the very ‘Father of our Country’ in whose honor George Washington High School had been named, was out of the ordinary,” Bogart writes.

She sounds more like a cheerleader than a critical thinker. A great many WPA artists, some of them Communists and fellow travelers, depicted a view of America that contradicted the American dream, as art historian Bram Dijkstra shows in his brilliant 2003 book, American Expressionism: Art and Social Change 1920-1950. Arnautoff wasn’t a lone artist crying out in the wilderness. His George Washington murals aren’t typical of WPA art, though with thousands of artists painting under the auspices of the WPA it’s not easy to say what’s typical or not.

Arnautoff’s fresco titled “City Life,” recently restored at Coit Tower in San Francisco, is more in keeping with the working-class and class-conscious ethos of the WPA and the 1930s. There don’t seem to be any people of color in the crowd scenes in “City Life,” though many of the paintings that are reproduced in Dijkstra’s American Expressionism depict African Americans, women, immigrants, and the pain and suffering unleashed by capitalism.

“Expressionism seeks to make us confront the harsher realities of existence,” he writes. “It calls upon us to acknowledge the raw, emotional core of experience and demands that we confront the inner conflicts that make us feel human.” In his Washington murals it’s as though the Russian-born Arnautoff wanted to say “I’m as American as George Washington.”

One might also argue that the murals at the high school are Communist propaganda. After all, under Earl Browder, the CP-USA adopted the slogan, “Communism is 20th century Americanism,” and did little or nothing to confront or antagonize President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal for most of the 1930s and ’40s. The CP viewed the founding fathers, especially Thomas Jefferson, as political progenitors of the Bolsheviks. Hence the CP-backed school was called “The Jefferson School.” Lefty books from International Publishers were sold at the Jefferson Bookstore in Manhattan.

Journalists who have written about the controversy surrounding the murals have quoted Arnautoff, who said in 1935. “As I see it, the artist is a critic of society.” Robert Cherny, the author of Victor Arnautoff and the Politics of Art, says Arnautoff “was a major artist, an artist on the left who was being very critical of Washington for owning slaves, and he was critical of the genocide of Native Americans.” At a school board meeting, Cherny said that the purpose of the murals was to provide a “counter narrative” for students about westward expansion and the country’s slave trade.

Critics have insisted that the artist’s purpose and intent no longer matter. One George Washington High School parent, Amy Anderson, argued that “The Life of George Washington” represents a colonialist perspective and validates white supremacy. One can argue forcefully that the murals should not be covered over or hidden, but one can’t tell parents like Anderson not to see what they see. Art is in the eye of the beholder.

Arnautoff’s murals privilege George Washington. He’s the star of the show; everyone else is in the background while he dominates the foreground. Moreover, the murals tend to be static; there are images of men with guns, but conflict isn’t embodied in the design of the murals. Part of the problem may be, not with Arnautoff’s politics, but with his art. Unlike Diego Rivera who created dynamic murals that seem to bounce off the walls, Arnautoff offered a series of tableaux that sit on the walls.

Dewey Crumpler’s murals, “Multi-Ethnic Heritage: Black, Asian, Native/Latin American” (1974), which are also at George Washington High School, look and feel much more vibrant and alive than Arnautoff’s work, in part because of the swirling colors and shapes. A digital image of Crumpler’s murals was included in the 2017 Tate Modern’s exhibition “Soul of a Nation” in London.

His murals, which are a response to Arnautoff’s, are fluid and elastic. Crumpler said that he first saw the George Washington murals when he was a teenager in the 1960s and found the images of African Americans and Indians shocking and “horrible.” He remembers that in 1966 students who were also Black Panthers wanted the murals removed.

“The African-American students saw a celebration of George Washington and his slave-owning,” Crumpler told Artnet. After a visit to Mexico and meeting with muralists like Pablo O’Higgins and David Alfaro Siqueiros, Crumpler changed his mind about Arnautoff’s work. “People are not taught how to read art and artistic imagery,” he said. “They don’t understand how it operates. They are trying to look at images literally, not euphemistically, not symbolically.” Crumpler’s own work operates symbolically and mythically rather than realistically, though it also invites viewers to rethink art itself; to see it as a cultural entity created by artist and by audience.

Don’t get me wrong. I love WPA murals. When I was a boy my father took me to post offices to see the work that was done in the 1930s. These days, I’m with the citizens who don’t want the murals destroyed and who would like them to be used as teaching tools in the classroom and in the community. But it also seems to me that the foes of censorship are too quick to dismiss those who see the murals as racist and who don’t find a touch of irony in Arnautoff’s portraits. Indeed, one person’s irony is another person’s cruelty.

Gray Brechin, the project scholar of the Living New Deal at the University of California, Berkeley, emphasizes the importance of preserving memories of atrocities. “The Jews never want what happened to them to be forgotten,” he told The New York Times. “That’s why they have so many memorials.” But Brechin’s comments sound opportunistic and disingenuous. Connecting the Arnautoff murals to the fate of the Jews during WWII seems over the top and not relevant, though some Jews argue that Arnautoff’s images are as bad as Nazi art that demonized their ancestors and led to the Holocaust.

One wonders why Arnautoff didn’t include depictions of Jews. After all, he was Jewish and Jews played important roles in the United States before, during, and after the American Revolution. Jews fought on the side of the colonialists against the crown and Jews helped to finance the revolution.

It’s not only what’s in the murals, but also what’s omitted. We don’t see Jews and we don’t see colonial women: no Martha Washington and no Abigail Adams who wrote to her husband in March 1776 to say: “Do not put unlimited power into the hands of husbands. Remember, all men would be tyrants if they could.” You can’t be more explicit than that about the patriarchy. Arnautoff did include a sentimental image of Washington’s mother as an old woman. A subservient African-American woman stands in the background holding Washington’s coat and hat.

Art historian Dijkstra argues that the issues about art, audiences, popularity, and censorship go beyond George Washington High School and the Arnautoff murals. “In the U.S. the people who run the museums and who make the aesthetic judgments decide that a certain kind of art is obsolete and throw it away, as was done with a lot of WPA painting,” Dijkstra says. “In Europe they don’t get rid of it. They store it and when it comes back in fashion, they bring it out of storage and exhibit it.”

Dijkstra and his wife, Sandy, collect art from the 1930s and ’40s. Their house is packed with work that museums were ready to toss on the garbage heap. That’s one way to preserve art. It’s often the only way. Too bad it can’t also be preserved in public places where the world can see it. Alas, all over the San Francisco Bay Area there are plans to destroy WPA art. It won’t be obliterated if those who protest against censorship raise their voices as they have in San Francisco. Harvey Smith, the author of Berkeley and the New Deal and a staunch defender of the murals, argues that students are indeed in danger, though not by Arnautoff’s art. “Kids are traumatized by everyday life on the streets,” he says. “The San Francisco school board doesn’t address that issue.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Jonah Raskin, professor emeritus at Sonoma State University, is the author of 14 books, including biographies of Jack London, Allen Ginsberg, and Abbie Hoffman. His new book of poetry is The Thief of Yellow Roses (Regent Press).