German Art Without Jews

A pair of exhibits, one at Harvard Art Museums, the other at New York’s Neue Galerie, try to read the signs of a coming conflagration and its attendant guilt in works made under the rise and fall of National Socialism

With diligence and even-handedness, the Neue Galerie has sorted the pictures in Before the Fall: German and Austrian Art of the 1930s, into categories, such as “Still Life,” “Landscapes,” and “The Individual.” But the images here, with their sometimes-gloomy and sometimes-magical subjects, pumped with the adrenaline that comes before a fight, keep willfully reshuffling themselves in my mind. Before the Fall, opening this week, is the third show in a trilogy curated by Olaf Peters, focusing on art that signaled and responded to the fissures in German and Austrian culture and politics, ultimately rupturing and leading to war and the Holocaust. Whether they intended it or not, the artists who made these paintings, drawings, photographs, and graphic works during the first decade of the Nazi regime were witnesses and messengers—or, as the Austrian painter and graphic artist Wilhelm Traeger put it, they were seismographs of upheaval.

Unlike the often gritty, experimental, and perplexing work at Harvard Art Museums’ Inventur: Art in Germany 1943-55, which is running contemporaneously, the art in this exhibit was made while the disaster was still unfolding. Social and political conditions were disintegrating, but the future hadn’t arrived; the art was laden with intimations of the tragedy to come, and this is incorporated in the installation design with its gigantic mourning veil and blackened tree roots projecting down from the gallery’s ceilings. Most of the artists remained in Germany or Austria and skirted their way cautiously around National Socialist constraints (in at least one case, even embracing them). Several were attacked as degenerate artists and lost their jobs. Some were internationally famous, such as Max Ernst, Oskar Kokoschka, or Max Beckmann, and chose to live abroad in exile. The selection includes a number of Jews—Felix Nussbaum, Hans Ludwig Katz, Friedl Dicker-Brandeis, Erwin Blumenfeld, Erika Giovanna Klein, and Helmar Lerski—each of whom experienced a different fate. The images are almost entirely figurative and stylistically diverse, reflecting principles of Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) and Surrealism, but also reaching back to Romanticism and sometimes even farther back to vanitas still lifes with flowers, figurines, and pinned butterflies. The anachronisms, particularly the still lifes with odd juxtapositions—a Japanese doll and a wilting poppy, for instance—are chilling harbingers of something deeply unsettling.

Neue Galerie tends to recirculate key pieces from their collection in these special exhibits, and two of their paintings, Beckmann’s 1938 Self-Portrait with a Horn and Felix Nussbaum’s 1940 Self-Portrait in the Camp literally form bookends to the exhibition, appearing on the front and back covers of the beautifully published catalog. Beckmann painted his masterpiece when he was living in Amsterdam. Like much of his work, the painting is designed as the tableau of a dramatic performance with the main and only character—the imposing figure of the artist himself—positioned just behind a not-quite pulled-back curtain. Dressed in a bold black-and-orange-striped dressing gown, with his hand comfortably placed inside the hollow of a horn, he holds out his single prop, and his message comes across as an un-hearable but instantly understood call of distress coming from inside the frame of a silent movie. For Beckmann who had served as a medical orderly during WWI, the horn’s role in signaling the arrival of something to come was obvious. With darkly shadowed eyes and a wrinkled brow, he looks out of the shadows, and you wonder if he’s still listening to the echoes of WWI or the approaching rumblings of the one that was to follow.

Beckmann’s self-portrait looks forward to an unavoidable cataclysm. It’s answered by Nussbaum’s self-portrait that gazes backward at a recent and devastating past and then half-questioningly forward to tragedy postponed. Painted in Brussels while he was in hiding. Nussbaum’s story is not so well known but should be. He was a German-born Jewish artist who spent much of the 1930s in flight, trying to find a safe place to live and work. In 1940, while he was with his wife In Belgium, he was arrested as an enemy alien and sent to St. Cyprien in France. Later, he escaped from a transport that was taking him back to Germany. Fleeing to Brussels, he reunited with his wife and went into hiding, continuing to paint in a basement space provided by a friend. The couple was denounced and arrested in 1944 and deported to Auschwitz where they perished. Unshaved, wearing a patched jacket and frayed cap, the artist looks out from the profound depth of suffering (and, I would say, accusation) while the grotesque backdrop of St. Cyprien, with the pitched roofs of its huts and barbed wire, surrounds him. Like the Flemish portraits he studied and admired, the painting tells his story, presenting a shocking depiction of the wasteland of the French internment camp with bones scattered in the sand. In the background, a despairing prisoner sits at a jerry-built table, while a man, stripped to his underwear and clutching some straw for cleaning himself, bends over with dysentery. Another, just a blanket over his shoulder to protect from the cold or his shame, empties his bowels in a waste pot.

Two other paintings in the Neue exhibition present themselves as a natural pair of opposites: Richard Oelze’s silent, brooding, and dystopic Expectation, created in Paris in 1934, and Karl Hubbuch’s Children Growing up under Stones, clandestinely painted on board in 1934 in Germany, after he had been dismissed from his teaching position as an anti-Fascist. In Oelze’s surrealist composition, a group of men and women congregate in an uncanny landscape, all but a few with their backs to us. Mostly, we view a sea of overcoats, the back of their hats—Homburgs, Bowler Hats, the women wearing stylish turbans, one has a felt brim hat. Mysteriously silent, predominantly faceless, they are simultaneously sleepwalkers and the crystallization of dread. Alternatively, Hubbuch ’s crowd of children is anarchic. The children appear to be little savages, playing with hoops, sticks, rakes, canes, and sieves in a sordid courtyard that looks like a setting from Mackie Messer’s Berlin. Thuggish faces stare out of windows. A prostitute and a derelict potential customer stand to the side. One little boy rides on another’s shoulders; one sticks out his tongue; another is pulling someone’s hair; one holds a stone behind his back. The disaster is about to occur.

***

The linocuts from Wilhelm Traeger’s Wien series document the sinister undercurrents of daily life on Vienna’s public streets as well as inside a coffeehouse and a parlor where the dead are laid out; he calls it Farewell in the Death Room. The sharp incisions of his compositions create a throbbing, oppressive, and comprehensive world populated by brothel-keepers, the ragged unemployed, tramps, rich old men in fur-collared coats, tarty prostitutes, beggars on crutches, lecherous eyes, crooked grimaces, broken teeth, skeletal hands, placards, posters, and journals bearing the news. The catalog includes an insightful passage from an interview Traeger gave in 1979, in which he was asked about prescience and responsibility. His answer was painstaking and thoughtful, reflecting that knowledge of the catastrophe didn’t come suddenly in the shape of an omen, but was conveyed over time through the ordinary and ongoing details of daily life. Traeger didn’t consider himself a visionary but spoke about the complex impulses spurring his work: “The more those experiences left behind strong impressions, the more I tried to sublimate them and thus aestheticize and ultimately get free of them.” To free himself from the burden of seeing, he explained, unheroically or heroically, he transformed what was in his mind’s eye.

The show also includes a rich selection of photographs, including Friedl Dicker-Brandeis’ avant-garde and anti-fascist posters, Helmar Lerski’s haunting illuminated studies from his series Transformations of Light, and a rich selection from August Sander’s mesmerizing Face of Our Time. Sander’s Children Born Blind would have stolen the show except that it’s hung in the narrow space of the second floor’s gallery hall, where it’s difficult to focus on anything for too long. From the early days of his career, starting in 1911, Sander shot photographs of people from all walks of life and ranging over Germany, placing them in categories according to profession and social groupings. The photograph of two blind children, a little boy and a little girl in ragged and dirty clothes, belongs to the category Sander labeled the “last people,” those who were dying or had disabilities.

Sander positioned his subjects adjacent to a neutral brick wall and waited with patience and gentleness for the graced moment of seeing and not seeing. The resulting photograph invites the onlooker to take the time to look at every thing and every texture: the mortar joints of the brickwork, the loose stone of the pavement, the little boy’s stained smock, stripes of the little girl’s jumper, the plaid of her underdress, her scuffed shoes and bruised shins, the dirt on her arms and hands. Maybe she’s seven or eight years old. The little boy might be slightly younger. You see how the little girl lowers her eyelids in protection from the light. Lost in conversation, she raises her left hand to the height of her shoulder. The little boy, struggling to make it out, squints in that direction. With her right hand, the little girl, in a motherly way, draws his hand close to her side.

The psychological insight of the photograph is profound, and it elicits a train of thought about illuminated vision, humanism, the dangers of typecasting, about Nazi policies, euthanasia, and the death camps, about seeing and knowing, and seeing people who are not seeing. The image is a link back to the compassionate work of Käthe Kollwitz and Ernst Barlach, artists of courage and character, who wanted to “do something” about war and the injustices in an imperfect society. It makes you wonder all over again about what art can—and can’t—do.

***

Just a few hours up I-95, Ernst Barlach’s majestic terracotta Crippled Beggar, an icon of humility and suffering, stands in the east arcade of Harvard Art Museum’s courtyard. It was fired out of glazed terracotta in Lübeck in 1930 and purchased by Harvard’s Busch-Reisinger museum in 1931. Weighted and weightless, geometrically simple but naturalistic enough to hold onto and lean down on a set of crutches, the subject of the sculpture is a symbol of the miseries and woeful inequities that were a legacy of World War I. It would be a lot easier for visitors to the Special Exhibitions Gallery two floors above if Inventur: Art in Germany, 1943-55 yielded the same moral clarity. It doesn’t.

On view until June 3, Inventur is a fascinating selection of 166 objects—sculptures, paintings, works on paper, book art, fabric, ceramics, photographs, and wallpaper—made by modern German artists who didn’t emigrate but experienced WWII and fascism in Germany. Some of them, like the Dadaist Hannah Höch and Expressionist Otto Dix, were famous before the war. Several fought as patriots in WWI. Many were dismissed from university positions in the 1930s or were sanctioned for making degenerate art. A few lived in the debatable sphere of “inner emigration” where they were members of the Reich Chamber of Culture and could try selling work under the radar of the regime. Willi Baumeister, Oskar Schlemmer, and Franz Krause resisted the censors by working at the Herberts & Co. lacquer factory in Wuppertal where they produced a series of lacquer panels with magnificent and brilliantly colored pooling, bubbling, and trickling abstract patterns. A large number of the artists were drafted in WWII and detained in POW camps after the surrender.

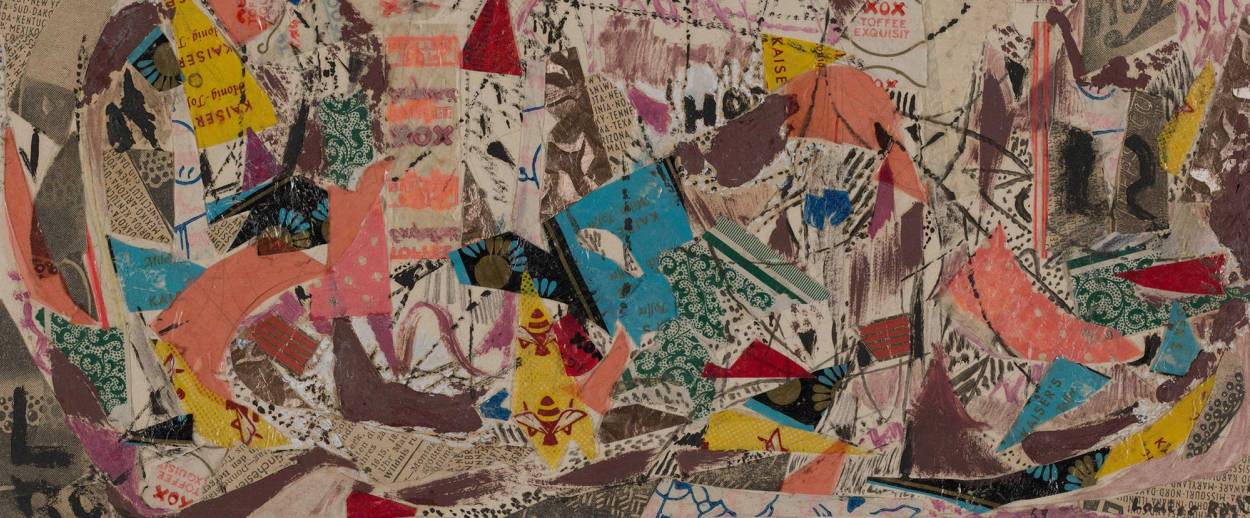

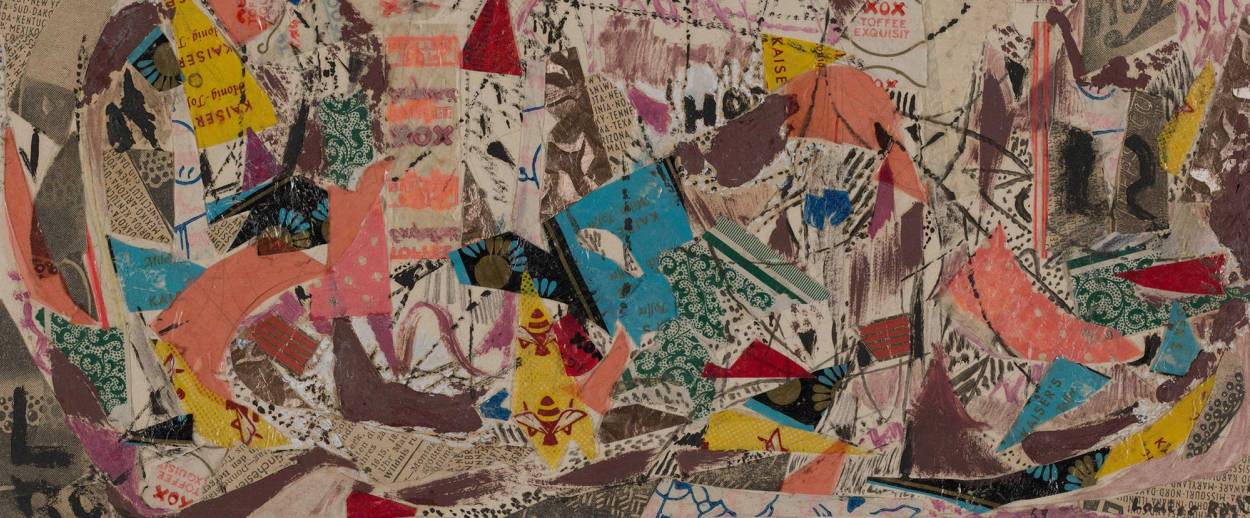

Much of the exhibit concentrates on art that shows the devastation of war, the fearful night skies, bombed out buildings, dusty hills of rubble, unburied corpses, POW barracks, barbed wire, and the scarcity of goods, including art materials. You look at this work for coherence, but instead, it yields ambiguity, equivocation, and sometimes heartbreaking diversion. A jewel-colored and whimsically ornamented watercolor on paper, covered with a scramble of dots, stripes, saw patterns, and X’s, glistens like postwar candy wrappers. The artist, Louise Rösler, had studied in the 1920s with three esteemed painters: Karl Hofer, Hans Hofmann, and Fernand Léger. Her husband was drafted and sent to Norway in 1939 before disappearing on the Eastern Front in 1945. Her Berlin studio was bombed, and almost all of her early work was destroyed. She and her young daughter were evacuated from the city and sent 240 kilometers south to a one-room apartment in Königstein where she remained until 1959.

Her composition, The Shop Window, celebrates the postwar introduction of the Deutsche Mark and the end of food shortages. Reaching down into deep interior space, she came up with this shimmering composition, just about the size of letter-writing paper. Where did she find the strength? What about her losses? Her husband? Neighbors in Berlin? Perhaps Jewish neighbors? You might ask: What about Jewish grocers? You won’t see them. Rather, the exhibit offers an invaluable opportunity, if you can bear the experiment, to revisit the disaster through German eyes, trying to understand the role of the individual living under totalitarianism and to think about compromises, complicity, costs, and the grace of survival.

***

The title for the exhibit, Inventur, is taken from a poem by Günter Eich, written while he was interned in an American POW camp in 1945. At that time, approximately 8.7 million German men were housed in camps throughout the four zones. Taught to school children in Germany, the text has come to define Germany’s Stunde Null, zero hour, the point of unconditional surrender often thought of as a break in history although today the concept is disputed. The poem, taking the form of a spare and unemotional list of an ex-soldier’s meager belongings, runs on a sound loop in the galleries: “This is my cap/this is my overcoat,/here is my shave kit/in its linen pouch…”

The speaker is the postwar German Everyman, and his stocktaking comes from the base point of identity where freedom is exercised in the smallest increments. Using the simplest words, in contrast to the degraded official language of Nazi propaganda, the speaker makes two confessions: he’s hidden the nail he used to scratch his name onto his mess plate and, he says, “there are a few things that I discuss with no one.” A name preserves identity, and the tucked-away nail is reminiscent of the chipped piece of glass or the coin wrapped in cloth that a Jewish slave laborer might have hidden inside a cap or the lining of a pocket. But what exactly are the things that can’t be talked about? What has he seen? What has he done? What did it mean to have been a German soldier? We don’t know. His inventory is about the private self, about integrity and disintegration, about holding and withholding, and about resistance.

Curt Querner’s drawings also come out of the zero hour. A member of the German Communist Party in the 1930s, he was, for a brief time, a student of Otto Dix. In 1940 he was drafted into the Luftwaffe, and after the war, he was sent first to an American POW camp and then a French one. My Stool in the De la Tubize Detention Camp from 1946, was executed in pen and ink with harsh, dark calligraphic strokes for the camp seat and some impatient scribbling to convey the splintering wood grain of knobby boards. Meticulous, almost obsessive layers of crosshatching build up an ambiguous dimensionality for Querner’s crudely built stool, which defiantly fills up almost all of the entire paper. Stylistically, the drawing brings to mind the surviving art from Theresienstadt, the work of Bedrich Fritta, Leo Hass, Otto Unger, Karel Fleischmann, and Peter Klein, for instance, who also represented a world that stood on unstable ground with forms threatening to break out from their outlines. But what can we make of Querner’s isolation? Does the camp stool represent the recovery or return to an interior world or is the drawing a gesture of understandable opposition? Again, the answer is unclear.

Ecce Homo Dying Warrior, one of the most harrowing pieces in the exhibit, was made by Gerhard Altenbourg in 1949 when he was 23 years old. Altenbourg had been drafted at the age of 19 to serve in the nightmare battlefield of the Eastern Front. When he killed a Russian boy-soldier, he became obsessed with guilt and his grotesque, flayed, and stitched-together figure, with wide open eyes, and a Bosch-like hand pointing to his heart, memorializes that event. Both a work of art and a document, the drawing in graphite lies on top of two connected pages of his boyhood crayon sketches, with tanks and soldiers on the bottom and flying dream-creatures on the upper page. The ferocious embodiment of death juxtaposed to the child’s idealization of war gives visible form to an artist’s conscience, and it’s one of the only works in the exhibit that straightforwardly demonstrates a feeling of guilt.

Konrad Klapheck, who was born in 1935, is the youngest artist represented in the show. He was only a boy when he saw his grandparents’ house in Leipzig go up in flames during a 1943 bombing raid. He was the featured speaker at the opening lecture for the Harvard show, and he remembered there how his uncles lamented: “Three Steinways in one house!” “Yes,” Klapheck said, “They were right.” He paused for a moment and continued, “On the other hand, I thought, the red [of the fire] is very beautiful.” As the child of two art historians, Klapheck was determined to become an artist but wasn’t certain of the way forward. His interior debate says a lot about the options that were open to German artists at midcentury.

Klapheck considered the gigantic artistic talents in Germany before the war, those at the Bauhaus or working in the style of Neue Sachlichkeit, New Objectivity. As he put it, “In art, usually, one is standing on the shoulders of another one.” And he contemplated the divide, hotly debated in postwar Germany, between the figurative tradition and abstract art. Jackson Pollock’s action paintings were greatly appealing, and many students experimented along those lines. Klapheck, who is precise, self-deprecatory, and has an exceptionally original mind, didn’t see that as his way.

In 1955 he rented a boxy vintage Continental typewriter from a shop for six marks a week. The machine had a side panel opening and carriage clamping wedges that look like small antlers. He painted it, exploring the illusion of volume and that was the beginning of what he calls Klapheck style or machine art. Over the years he has painted 43 typewriters and many sewing machines, irons, faucets, bicycles, bicycle bells, drilling machines (which he called “the big brothers of the sewing machines”), gas masks, tires, and shoe trees. He described making isolated objects the subject of his paintings as “very personal.”

In his conclusion, Klapheck turned to the work of the German Jewish Artist Felix Nussbaum, whose painting at the Neue Galerie, Self-Portrait in the Camp, gazes out from the horrors of St. Cyprien. Klapheck told the Harvard audience Nussbaum’s story: “a Jewish painter, born in Osnabrück, he lived hidden in Brussels in the shadow of his beloved Flemish artists, Bruegel and Van Eyck.” He went on to describe how Nussbaum was denounced, transported, and memorialized today in Osnabrück with the Felix Nussbaum Haus. It goes without saying that in 1945, at the zero point, Germany didn’t have Jewish artists. And if an inventory involves taking stock of what we have, it also, by necessity, involves taking stock of what we lack.

***

Read more of Frances Brent’s art criticism in Tablet magazine here.

Frances Brent’s most recent book is The Lost Cellos of Lev Aronson.

Frances Brent’s most recent book is The Lost Cellos of Lev Aronson.