1.

North of Jerusalem rises the hill called Ba’al Hatzor, the highest in the West Bank, named for the old Canaanite god worshiped at peaks like this with human sacrifice, and mentioned in the Bible as the scene of a royal fratricide. When I was there late one afternoon, walking between an old cistern and a few twisted oaks, the hilltop felt stark and unsettled, though that might just have been because of everything I knew. The place kept its secrets. It was hard to match the landscape to the sketch made by the forensics team. There was no trace of the German or his temple.

I first heard of Erich Gunther Deutecom from a family friend in Nahariya, the northern town where my parents live. This town was founded by German Jews, and in the early 1960s, the war barely over, it was a place full of people with terrible stories that were alluded to in whispers if there were children around. Many residents had part of their minds shaken loose by what they’d seen, so Deutecom wasn’t unique in that way. And there was nothing strange about the fact he spoke German: Almost everyone in the town knew German, even if they’d sworn never to speak it again. He was unique because he was the other kind of German.

You can explain Israel with the kind of stories that people are used to, narratives about politics, leaders, or wars. But if you spend enough time here, you meet characters driven by forces that rationalists find it hard to take seriously or even to grasp—forces like the voice of God, for example, as detailed in Scripture if you just know where to look; or the propulsive force of violence perpetrated in different times and places, and the lessons it seemed to teach; or urgent schemes for cosmic repair. The country can’t be understood without people like Deutecom. I spent months trying to unravel his story, one whose ambiguities gestured mutely to the black hole that Germany created at the center of the 20th century, to the aftershocks of that event in this country, and to the chances that humans can ever fix what’s broken.

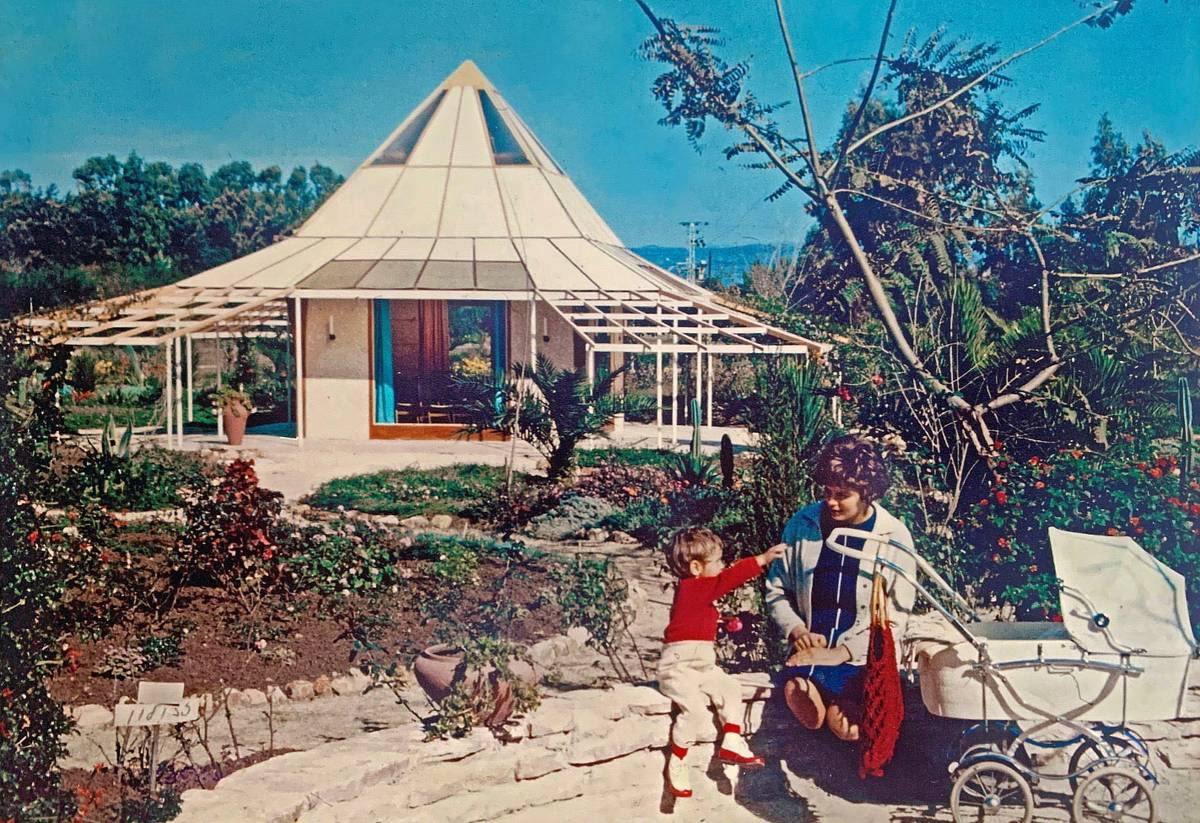

There’s a small botanical garden you can visit today in Nahariya, a tidy enclosure of tropical plants stalked by peacocks and third-graders. I’d passed it hundreds of times but didn’t know, until informed by Rafi Levinson, a friend of my parents, that it began as a park created by a mysterious stranger who disappeared decades before. This earlier park was divided into 12 sections, one for each of the tribes of Israel, arrayed around an odd structure known as the Tabernacle. The German had created the park with his own hands and money, giving the town a rare public plot of green in a scrappy area where most open spaces were used for cows or cabbage.

There’s no trace of Deutecom’s name in the garden, or anywhere in the town. But people who were children at the time remember him: A tall, blond man of military bearing, riding erect on a blue bicycle. Aya Megdi, 70, who was raised in a German-speaking home next door, described a man of culture, an architect who spoke polished hochdeutsch. “He was handsome, totally Aryan,” she told me. In his house, which he designed himself, he had books and detailed plans for extraordinary buildings. Much later he’d be described as a kind of lunatic; the most comprehensive article written about him in Hebrew, published 30 years ago, referred to him as an “eccentric.” But the people of the town don’t remember him that way at all. Deutecom was a man with unusual ideas, but he was sane.

In his park he strictly forbade smoking, this at a time when people smoked everywhere—a detail of his character that would recur, in dramatic circumstances, later on. On Fridays in the Tabernacle he’d screen cartoons for the children, usually with a biblical theme. Everyone knew he was Christian, but he asked to be called by a Hebrew name, Gideon. He had a wife back in Germany, and a daughter, and for a while they came to live with him in the town. The girl had Down syndrome, and Aya remembered that she used to spend hours walking around in circles. But after a while they went back home for good, leaving Deutecom with the Jews, with his park, and with the future plans he pursued with dogged and mystifying effort. The children saw nothing strange in any of this, or nothing stranger than everything seems when you’re young.

There were other German Christians around this part of the Galilee in those years. In a moshav south of Nahariya, for example, there were the Nothackers, Friedrich and Luise, who opened a rest home for Holocaust survivors in 1960. Just inland there was the Christian kibbutz of Nes Amim, where German and Dutch volunteers grew roses and tried to participate in the rebirth of Jewish life after the war. (This village, where I once worked in the greenhouses, is a short bike ride from the kibbutz called Ghetto Fighters, founded by survivors of the Jewish resistance. The western Galilee is an interesting and underappreciated part of this country.) The people in the town understood that Deutecom was a man of deep religious faith, and that he’d come to make amends—but whether it was for his people’s crimes, or for his own, it wasn’t clear. The truth is that no one really knew who he was.

2.

What do we know?

We have his name, though there’s dispute about the spelling: The most common would seem to be “Deutekom,” and in a brief dispatch from 1973 the Jerusalem Post rendered it “Deut-Akom.” But in the one example I’ve seen in his own handwriting, he spelled it the way I’m spelling it here. On occasion he was referred to as Erich Gunther, and on other occasions as Gideon Gunther. And there’s the possibility that none of these names were really his at all.

We know where he lived, at 6 Redemption Rd. A few months ago I was in the little house he built, sitting on a couch with Dr. Shaul Shasha, who’d bought the property from the German five decades before. The botanical garden was next door, and out the window glimmered a peacock that had just jumped over the wall, as if sending regards from the man I was looking for. Shasha, 83, recalled how Deutecom sold him the house after canceling a deal with an earlier buyer who turned out to have a smoking habit.

The doctor was happy to meet an educated man out here in the provinces. They had long conversations at the time, and kept in touch, so henceforth Dr. Shasha would be considered the local authority on Deutecom. “He was meticulous, a yekke, like a soldier,” Dr. Shasha said, using a Hebrew term for Germans. (The term literally means “jackets,” because the German Jews who showed up here in the 1930s wore clothes that the sabra pioneers considered ludicrously formal.) “The story,” the doctor said, “was that he’d had a dream where an angel told him to come to the Land of Israel and build the temple.” Nahariya was never more than a station on the way to Jerusalem, he said. “But you don’t build the temple right away. You have to make a long journey.” When Israel captured the Old City and the Temple Mount from Jordan in 1967, Deutecom understood that his plans had been given divine sanction.

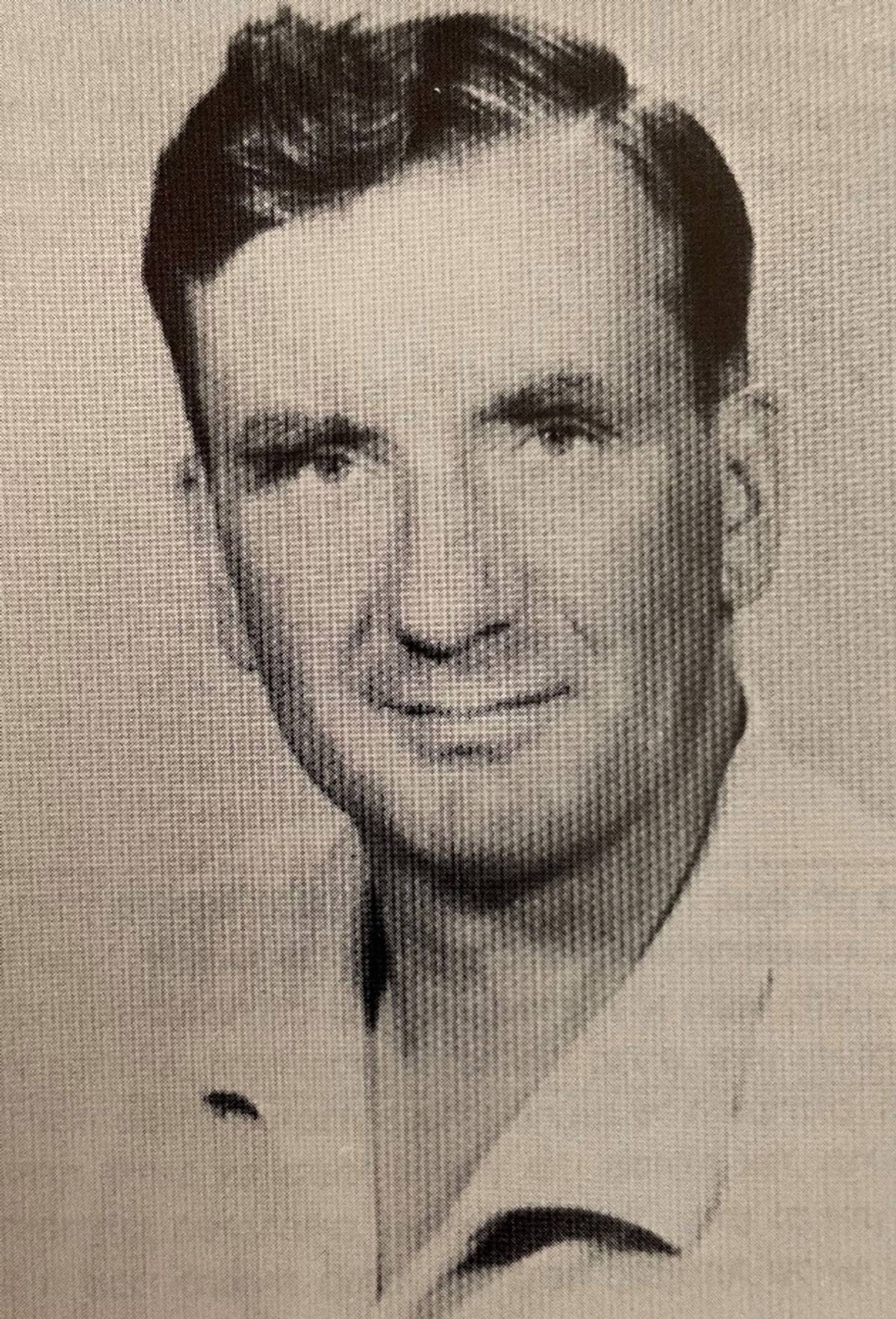

We have one photograph of the man, from the article “The Eccentric of Ba’al Hatzor,” published in a Hebrew academic volume in 1993. (The book is Samaria and Benjamin, edited by Ze’ev Erlich, a veteran field guide and keeper of Land of Israel esoterica from the settlement of Ofra, who assisted me in my inquiries and generously granted me permission to reproduce the photograph and the documents that appear here.) Much of what we know is thanks to the author of this article, the journalist Yehuda Litani, who covered the West Bank for Haaretz in the ‘70s and ‘80s and took a personal interest in this case.

According to police documents obtained by Litani, the German was born around 1918. He might have been from Munich—at least he seems to have had family there, and some property that generated money. But Aya Megdi, who lived next door and grew up speaking German, said his accent wasn’t that of Munich. What is clear is that when the Nazis launched World War II he would have been about 21, precisely of military age.

Whatever happened next is clearly at the center of Deutecom’s strange life, but the facts are elusive. According to Litani’s account, he fought in North Africa with Rommel’s Afrika Korps, a version of events for which no source is given, but which might be true. It’s also true, however, that this would be a good story to tell a town of European Jews, because it would place him far away from the unmarked graves of their relatives. One can be forgiven for suspecting that a mission to the Jews as exceptional as the one Deutecom was attempting might be driven not by a general sense of responsibility but by the memory of something he’d done with his own hands.

There seems to have been a rough division among residents of the neighborhood: People who escaped to Israel before the war were open to him, while those who experienced the genocide in Europe were not. Aya Megdi said her German father never felt comfortable around Deutecom, but didn’t think it was because he suspected the stranger was a Nazi. It was, she thought, because he was educated and made her father, a farmer, feel inadequate. When I spoke to Effi Wildman, another neighbor who was a teenager at the time, he said his parents avoided the German altogether. They always believed, he said, that he’d served on the Eastern Front. There’s some statistical logic to the idea, as that’s where the bulk of the Wehrmacht was engaged at the peak of the war. That’s also where millions of Jews were shot, gassed in trucks, or deported to death camps by Germans around his age.

Over the past few months a journalist in Berlin, Daniel Mosseri, ran checks on Tablet’s behalf in the archives housing Wehrmacht records. The archivists found no soldier or officer with that name. The same reply came from the archive that keeps the lists of Nazi party officials and members of elite arms of the Third Reich, like the SS and SD. If Deutecom served in any of those organizations, either his file hasn’t been found, or he was there under a different name.

Pursuing this story felt like excavating those burned scrolls in Pompeii that disintegrate when you touch them. The journalist Litani, for example, seemed to have been given a trove of the German’s own documents decades ago—but when I called him at home, his daughter answered and seemed surprised. Her father had died five days before, and they were sitting shiva. When I interviewed the 83-year-old Dr. Shasha in the German’s old living room, he seemed in good spirits. He died the next week.

3.

In the early 1970s the German abandoned his park and Tabernacle. “I think he left disappointed. Not everyone accepted him,” Aya Megdi, the German’s neighbor in Nahariya, said.

He next surfaces in a small agricultural village called Segev, in the hills of western Galilee. Here, too, he planted a garden, this one of cacti, and invited local children to help out, according to a brief account written for a local newsletter by a resident named Yisrael Ben-Dor. He was treated respectfully by his neighbors, Ben-Dor wrote, but didn’t stay for long. He sold his house to a man named Oskar Eder. This Eder would go on to found a coexistence center known as the Valley of Peace, and would convert to Judaism, taking the name Asher. He’d been a Luftwaffe pilot in the war.

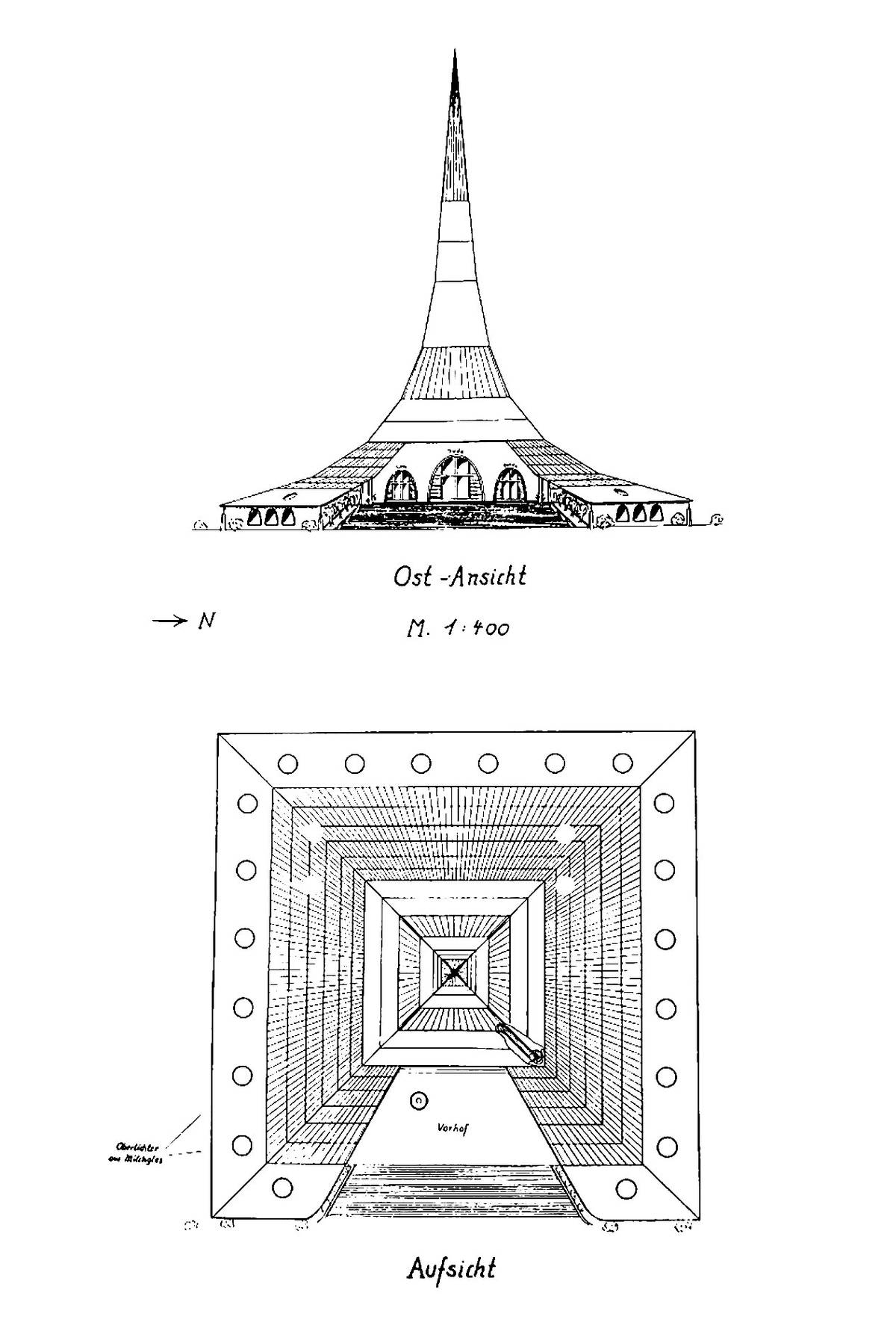

Among Deutecom’s papers are sketches of a grand structure he called the Friedens Tempel, or Peace Temple, which he meant to build in Jerusalem. The temple would bring together Jews, Christians, and Muslims, echoing the biblical description of “a house of prayer for all nations.” The sketches are mesmerizing, evoking both the craft of a skilled architect and the intricate madness of a bearded American who once approached me at the Hebrew University library, unrolling detailed maps tracing what he believed to be the true path of the Exodus from Egypt. He’d spent years drawing them. This man, who was well-known around Jerusalem, believed he was King David. He died of exposure in a cave outside the city a year or two later.

When Mayor Teddy Kolleck received the plans, he responded as you’d expect—the mayor of Jerusalem gets temple proposals like other mayors get parking complaints. When the journalist Litani asked Kolleck about it, the mayor said that if he got the German’s request he certainly threw it out: “I didn’t, and still don’t, have time for lunatics.” If Deutecom was discouraged, he wasn’t deterred. That’s how he finally ended up in the hills north of Jerusalem, by the Palestinian town of Silwad, in the territories Israel had captured from Jordan five years before.

This hill, known in Arabic as Jebel Assour, wasn’t the Temple Mount, but from its peak you could see to Jerusalem and across the land—from the Mediterranean in the west to the hills of Jordan in the east, and all the way to Mount Hermon in the north. The Hebrew name of the place, Ba’al Hatzor, appears in 2 Samuel as the scene of an episode that happens not long after one of King David’s sons, Amnon, rapes his half-sister Tamar. Another of the king’s sons, Avshalom, invites Amnon to the hill to celebrate as their shepherds shear the goats, gets his brother drunk, and then avenges the rape by killing him and leaving his body on the hill. Avshalom himself wouldn’t last much longer. I spent an hour or two up there. The hill named for the Canaanite deity still feels like a place governed by the darker gods. As the sun crept down to the western horizon, I was eager to leave.

Today the drive north from Jerusalem to the hill takes you through the West Bank’s impossible landscape, with its unhappy tangle of Palestinian villages hemmed in by army checkpoints and red-roofed settlements, including Ofra, one of the flagships of the religious settler movement. But in 1972 there still weren’t more than a few thousand Jews living in the West Bank. The future of the territories wasn’t clear. Deutecom bought a plot of land on the hill from a Palestinian family in Silwad, hired a few workers who brought a few donkeys, and began hauling up planks and cement. First he built a shack and moved in. He had a girlfriend in Jerusalem, and sometimes she’d come to stay with him. But mostly he was there alone, by the old cistern and the misshapen oaks.

4.

If he was unaware at first of the growing anger among Palestinians about people encroaching on their land, he couldn’t have remained unaware when his shack was burned the first time. And if he brushed off the first arson, it would have been harder to ignore the second. He asked the Israeli army for help, but the army didn’t have time for the German and his temple. He kept building. He struck people in Silwad as someone with a military demeanor. The townspeople remember him firing flares from the hilltop at night, an image that’s hard to shake—the old soldier staring into the darkness gripping a flare gun, perhaps remembering other nights of fear. Was it Tobruk? Stalingrad? Arnhem? A pit of women and children among Ukrainian pines? Who did he think was coming up that hill?

On Feb. 16, 1973, a 19-year-old named Ahmed al-Zeer was working in the agricultural lands of Silwad when a friend, Abdullah Fardan, walked over to talk about the stranger. They both believed, as al-Zeer later told police, “that we must prevent Jews and foreigners from buying land and building houses near us.” The Arab armies had failed in 1948 and 1967, the Jews had won, and people in the villages felt their backs against the wall. They decided to kill him.

One of them took a hoe and the other an iron pipe. They climbed toward the German’s shack, arriving before sunset, the same eerie time of my own visit five decades later. They struck up a conversation, al-Zeer said in his confession, and Deutecom “received us warmly.” When the Palestinians offered the stranger a cigarette he wouldn’t take it, explaining that he didn’t smoke—a detail like a fingerprint, indicating that this is a real description of the German’s last moments.

The sun was setting. Al-Zeer suggested he look at how beautiful it was, and when the victim turned his head al-Zeer struck him from behind. The German’s hat flew off but he was still conscious, and began to scream for help. Al-Zeer pinned his hands behind his back while his friend used the pipe. After a few blows to the head Deutecom fell silent. “I felt the German stop resisting,” al-Zeer said in his confession, “and let him fall.” The two assailants had the idea that his retinas might contain the last image he saw, and that the Israelis could somehow use this to identify them. That’s why they gouged out his eyes.

The murder was briefly reported in Israel. “Man found dead near Ramallah,” read the Jerusalem Post headline over a three-paragraph story. A scan of the main German newspapers of the time came up with no mention at all. When the police swept through Silwad looking for the killers they arrested al-Zeer, but he didn’t talk and they let him go. The crime remained unsolved. The German’s shack fell into disrepair, and by the time I showed up there were no traces I could find. His park in Nahariya surrendered to weeds, and at some point the Tabernacle vanished, no one remembers exactly when. A new botanical garden was built on the spot. He was forgotten, but not completely.

The person who remembers him best lives where he did all those years ago, in the town of Silwad, at the bottom of the hill. I located Ahmed al-Zeer with the help of a Palestinian colleague. The 19-year-old is now 68, but he seemed even older than that. He spoke in a frail voice, slouched on a couch, his swollen feet resting on a pillow.

He recalled hearing his neighbors talk about a stranger who’d bought land from a villager who shouldn’t have sold it. Maybe this man was building a hotel, they didn’t know. Everyone called him “the German,” but he had a Jewish name, Gideon, and the villagers were certain he was a settler. There were rumors, al-Zeer said, that this man was connected to the Shin Bet or the CIA. It was said that he kept a pistol. Everyone saw the flares he fired at night. Al-Zeer seemed curious about the victim, whom he called Gideon Gunther. He didn’t know much about him.

The men of Silwad tried to warn the neighbors who’d sold their land, but they refused to cancel the deal. “Land is a man’s personal honor, and when they didn’t retract, he had to die to protect our land and our honor,” al-Zeer said. The German’s death sentence came from military commanders in Fatah: “The decision was from the leadership, who said this man has no honor and if you can kill him, do it.” So he did it.

Afterward he escaped to the Gulf and tried to build a new life in Kuwait. When that didn’t work out he joined the PLO fedayeen training in camps in Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan. In the summer of 1976, three years after the killing, he and two other fighters were trying to cross back from Jordan with a shipment of rifles and hand grenades when they ran into an Israeli ambush. His two comrades were killed but he was only wounded, and his life was saved by doctors at Hadassah Hospital. That’s where the police took his confession, which he says he gave only after the interrogators showed him the signed confession of his accomplice, Fardan.

For obtaining and publishing the text of the original confession we’re indebted, as in so much else in this story, to the late journalist Litani, whose interest in the case turned out not be purely academic: He’d been a press officer in the army’s West Bank headquarters when Deutecom was on the hill, and his fiancé, also an officer, had fielded the German’s appeals for protection in the weeks before the murder. They hadn’t done enough to save him, he wrote. “Since then I’ve been going around with a sense of guilt about this man, whom I never met.”

An Israeli court sentenced al-Zeer to life. But nine years later, when the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command traded three captive Israeli soldiers for more than a thousand prisoners, his name was on the list and he walked. He ended up in Libya, drifted to Jordan, married, and eventually had eight children. He came back to his town after Yasser Arafat signed the Oslo Accords in 1993, and got a job with the Palestinian Authority, first as a lawyer and then as a military judge.

Twenty years after his return, in 2013, he was in his town’s agricultural lands at the foot of the hill when a group of young Israeli men approached from a nearby settlement outpost. At least one of the assailants had an iron bar, and they beat him within an inch of his life. There’s no indication they knew who he was. An Israeli human rights group published a photograph of al-Zeer in the hospital, his head bandaged and both eyes swollen shut. That report brought him back to the attention of the few people who take an interest in this case, and eventually led me to him.

He hasn’t recovered from the assault. He can barely walk, and moves around his house with the help of his wife. All of this happened a short walk downhill from where he’d once offered the German a cigarette, and suggested he turn around for a moment to see the sunset. There’s no peace temple at Ba’al Hatzor. This country might draw dreamers, but it has other plans. The hill remains an ambiguous place, one that suggests unsettling truths about humans while never quite revealing what it knows.

With reporting from Fatima AbdulKarim in Silwad, and Daniel Mosseri in Berlin

Matti Friedman is a Tablet columnist and the author, most recently, of Who by Fire: Leonard Cohen in the Sinai.