If it often seems that readers’ appreciation for writers stems as much from a fascination with the way they lived as an admiration for the texts they wrote, then Italian novelist Elsa Morante deserves a place among the most beloved literary celebrities. Living in Rome in the tense days of the late 1930s under Fascist rule, the beautiful young woman with sharp tongue and ambitious pen ran in prominent intellectual circles alongside Alberto Moravia, at the time one of Italy’s most famous writers—and also her husband. The glamorous couple spent their evenings in trattorias with artists, dissidents, philosophers, and filmmakers. When Mussolini fell and the Nazis occupied Italy, she and Moravia—both half-Jewish and he wanted for anti-Fascist writing—survived by hiding out in the mountains south of Rome and living among peasants. The experience inspired novels by both; the young Sophia Loren starred in the film adaptation of Moravia’s. In the heady postwar years, Morante had lovers but no children, traveled to India, Egypt, Israel, Turkey, the United States, and Iran, and continued to write. Her innovative and controversial literary output is as varied as her experiences: essays on aesthetics and art criticism, poems, short stories, children’s tales, and four major novels, including the epic History: A Novel, which garnered worldwide attention—including a ban by Franco in Spain—when it was published in 1974.

But Morante remains essentially unknown today in the United States; even in Italy, she has only within the last few years secured a place alongside Primo Levi, Italo Calvino, and Umberto Eco. Concetta D’Angeli of the University of Pisa notes that until recently, it was considered cruel to ask even the best students about Morante, given that her work—often misunderstood and not fitting neatly into specific trends—garnered only brief mentions in most textbooks.

This fall, Purdue University Press released Under Arturo’s Star: the Cultural Legacies of Elsa Morante, the first critical study of Morante published outside of Italy. In the introduction, its authors call her one of the greatest Italian writers of the century, noting that many younger Italian writers look to Morante as a literary model. “It is surprising,” write the book’s editors, Stefania Lucamante and Sharon Wood, “that, in a literary context dominated by male figures such as pertains in Italy, the inheritance of her individual stylistic and thematic signature is becoming increasingly visible.”

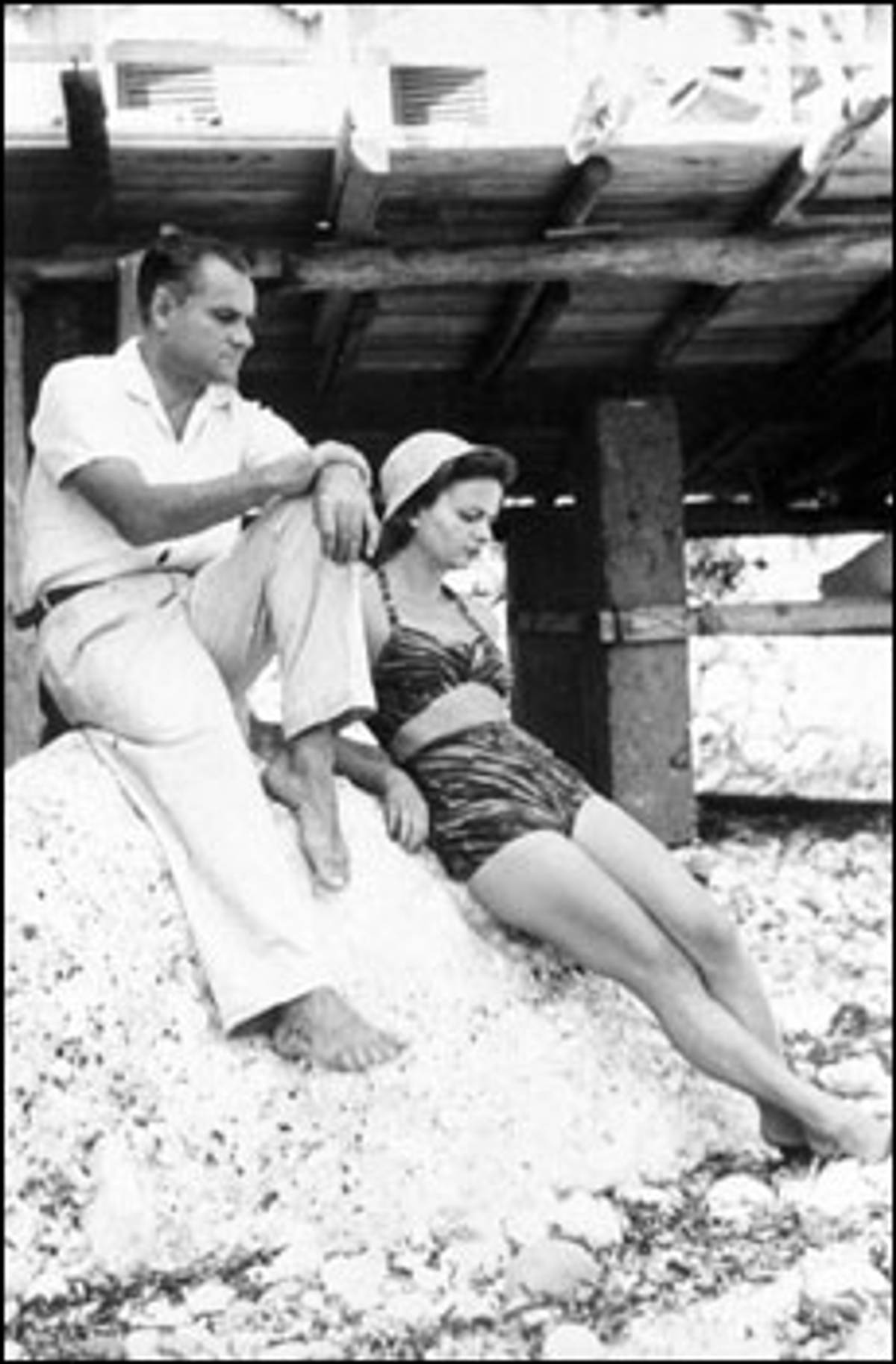

Yet whether this academic attention will end Morante’s obscurity in this country remains uncertain. Like the pioneering journalist and writer Martha Gellhorn, who will perhaps always be known first as Hemingway’s third wife, Morante has difficulty escaping the pernicious trap of spousal identity. But unlike Gellhorn, Morante was always known—even by members of her husband’s own circle—as the better novelist. Tempestuous and cold, fiercely argumentative (about art, not politics), Morante considered herself a genius. A beautiful woman—her niece, the contemporary Italian actress Laura Morante, looks just like her—she had what scholars now dub, diplomatically, a “difficult” personality. But her intense privacy has left us with almost no autobiographical writing; much of her biography, therefore, comes to us filtered through other writers, including Moravia himself, from whom she separated in the late 1950s.

These factors are compounded by challenges that affect most international literatures in English: poor translations, out-of-print editions, and the American public’s perennial lack of curiosity about foreign writers. Morante’s lyrical and exuberant prose, produced at a time when American writing tended toward pared-down precision, also poses difficulties for translators and for American tastes. If Italo Calvino is better known than Morante in this country, says Stefania Lucamante, it is because his concise prose is better conveyed in English. But, she notes, judging by the popular and critical acclaim for writers like Jonathan Safran Foer, American readers have clearly acquired a taste for baroque and ornate prose, like that of Morante. Unfortunately these are the qualities Lucamante finds lacking in English translations of her work.

Morante was born in 1912 and was raised in the working-class Testaccio section of Rome. Though her mother was a teacher, Morante didn’t attend school regularly until age 10, when her family moved to the other side of the Tiber. Yet she was a writer from the beginning. At 12, she wrote and illustrated a novel—”very charming, very well told,” according to Moravia—that won a contest and was published in a newspaper.

From the time she left home at 18, she lived—sometimes alone, sometimes with a lover, but always precariously—by writing. At 25, she met Moravia at a dinner party, where, he claims, she wooed him by slipping her key into his pocket as they said goodnight. In Life of Moravia, his book-length interview with Alain Elkann, Moravia says he was “fascinated by an extreme, heart-rending, passionate quality in her character.” He loved her, he said, but was never in love with her, having never “managed to lose [his] head.”

Their relationship followed a brutal arc of history. They met in 1937, the year Hitler visited Rome and signed a pact with Mussolini. In 1941, a year after the Italian dictator declared war, they were married by the Jesuit priest who had drawn up the concordat between the Vatican and Mussolini (and who would later refuse them shelter from the Nazis). During the ceremony, their witnesses discussed the top news of the day, the Battle of Stalingrad.

In 1943, the Nazis invaded Italy, and Morante and Moravia’s security came to an abrupt end. Having missed the chance to flee with a prescient friend before the Germans arrived, they hid in the occupied city for a few days before boarding a train to Naples. But the tracks had been bombed out partway there, so they disembarked and traveled on foot through the town of Fondi and into the mountains, with a donkey carrying their luggage. With only summer clothes and two books between them—the Bible and The Brothers Karamazov, which they would use for toilet paper—they expected the English to arrive within days. But they spent nine months there, surviving on one meal a day, bathing in cold water, and sleeping in a hut with a tin roof and packed dirt floor where puddles would form after it rained. They did not write nor read much, instead spending their time watching the landscape for signs of Allied progress. They watched dogfights between German and Allied aircraft and had one close call, when German soldiers came to their door.

While in hiding, Morante became frantic about the manuscript of her first novel, which she had stashed with a friend in the rush to flee Rome. So two months into the stay, at extraordinary risk to her life, she went back into Rome to retrieve winter clothes and check on the manuscript. Relieved to find it safe, she returned with a suitcase, which at one point a German soldier helped her carry. Though Moravia claims she said nothing about the city upon her return, the trip clearly had enormous consequences for History, the novel she would publish 30 years later about the occupation of Rome—and her identity as a Jew.

The manuscript that survived so precariously was published as Menzogna e sortilegio (Lies and Witchcraft) in 1948, the same year Morante and Moravia moved into a grand apartment on Via dell’Oca, a short street just off the Piazza del Popolo. Modeled after Don Quixote and Orlando Furioso, this mammoth family saga, set in Sicily at the beginning of the century, won a prestigious national prize, was contracted for an American edition, and elicited a vigorous critical outpouring from both extremes. The critic Georg Lukacs called it one of the most important Italian works of the century. Others vehemently mocked its length, its realism, and its 19th-century narrative form.

The novel had been mostly forgotten in Italy by the time the American edition appeared three years later, having been cut by nearly 20 percent, poorly translated, and given the title House of Liars, which infuriated the meticulous Morante. Lucamante compares the translation to a guillotine, immediately killing the possibility of Morante gaining any attention in this country.

Morante’s second novel, L’isola di Arturo (Arturo’s Island), in which an adult narrator tells the story of a boyhood spent in isolation on the smallest island in the Gulf of Naples, appeared in 1957. It won another top national prize but received scant attention here with its 1959 translation. It was not until 1974, with the publication of La Storia (History), that Morante again gained international attention. Her most important work, the novel tells the story of Ida Mancuso, a widow in Rome during the occupation who is raped by a German soldier who happens to be from a hamlet in Bavaria called Dachau. As a result, Ida gives birth to Useppe, the beautiful, loving, fantastical boy at the book’s heart who embodies perfectly the notion—very important to Morante—of ragazzini, children untouched by poisonous effects of adults. For its publication, she convinced her publisher to produce an inexpensive, paperback edition, so that ordinary people like those so richly depicted in the book could afford it. The novel sold more than 100,000 copies in its first month.

The 800-page tome is clearly autobiographical; Moravia, in fact, noted that in all of her novels, “without even much transfiguration, you find Elsa herself and the people in her life.” Ida, like her author, is half-Jewish, and her fear of discovery dominates the narrative. She agonizes over the racial laws and edicts, several of which are reprinted within the novel, even though, since her mother (again like Morante’s) had her baptized a Catholic, “no one seemed to doubt her total Aryan-ness.” Yet she is drawn toward the Jewish Ghetto—”by an impulse of obsessive necessity, like a planet gravitating around a star.” She begins to speak casually to shopkeepers there, from whom she gathers her news of the war and the deportations, no longer trusting others. She draws a chart—also reproduced within the text—of her elder son’s genealogy, trying to determine if he meets the four-generation criterion for Aryan-ness; she constantly believes “the guilt of her mixed blood” will “be read in her face.”

On October 16, 1943, one month after Morante went into hiding, Germans rounded up Jews in Rome. That date is mentioned on several occasions in the novel—and precipitates the book’s most harrowing moment, in which Ida sees the loaded train awaiting departure and recognizes a shopkeeper from the Ghetto: “The sound suggested certain dins of kindergartens, hospitals, prisons: however, all jumbled together, like shards thrown into the same machine.” One thousand fifty-six people were deported that day; the novel’s narrator notes that 15 returned after the war to be mostly ignored by a public unwilling to hear their stories.

When the American edition came out in 1977, Stephen Spender, writing in The New York Review of Books, called Morante a “storyteller who spellbinds the reader. Like Flaubert,” he continues, “she seems a great processional artist who can cover an enormous canvas, introducing, as the plot develops, new characters who are fixed and made convincing in a few swift strokes.” That comparison might have resonated with the critics who found Morante’s approach to narrative outdated. Indeed, the structure of the book, with each section set off by a list of contemporaneous world events—beginning with 1900-05, when “the latest scientific discoveries concerning the structure of matter mark the beginning of the atomic century”—could be misconstrued as heavy-handed were the characters and their story not so compelling and Morante’s artistic commitment to reality not so strong.

For Morante, art had to accurately reflect real life. “The only real artist is the person who has faith in his/her personal and authentic capacity to apprehend reality empirically,” she wrote. Yet first with Kafka, then Stendhal as her models, her notion of reality paradoxically encompassed what life should be rather than what it is constructed to be in bourgeois societies. Departing sharply from the trend for social realism that followed the war, Morante wrote that the function of art is “to prevent the disintegration of human consciousness in its daily, wearisome, alienating contact with the world; to continually give back to it, in the unreal, fragmentary, and consuming confusion of external relationship, the integrity of the real.”

Morante would publish one more novel, Aracoeli, in 1982; in it, the narrator travels to Andalusia to free himself of the memory of his mother. It received the least attention of her works (though it later won France’s Prix Medicis for best foreign novel) and, according to D’Angeli, “is still viewed with considerable hostility.” Immediately after its release, Morante attempted suicide. She spent her final three years in a private clinic fighting the depression that plagued her late in life and was brought on, at least in part, Lucamante argues, by her devastation over the loss of her beauty. She died in 1985, of a heart attack, at the age of 73.

The intervening years have seen a resurgence in her reputation, with the first two national conferences in Italy on her work in the 1990s. In 2000, Steerforth Italia released History in an updated English translation by William Weaver. The imprint’s inaugural publication, Open City: Seven Writers in Postwar Rome, included an excerpt from Lies and Witchcraft. And in 2003, Steerforth Italia reissued Arturo’s Island in its original 1959 translation. Tim Parks, writing in the New Statesman, captured the essence of Morante’s work, calling Arturo’s Island “rich, melodramatic and strangely, somehow naturally, balanced between realism and myth.” It contains “all the themes and debates of the postwar period,” he wrote, “treated with a comedy and profundity that matches Beckett at his best.”

It may be a long time before well-read American tourists flock to the cafes in Rome once frequented by Morante—and this is probably for the best. But it is time for international readers to recognize Morante’s place among Italy’s best writers of the 20th century. When the young William Weaver asked Morante to sign his copy of her first novel, he confessed that he had not yet read it, fearing what he calls “her diabolical instinct for vulnerable spots.” Her disarmingly joyful reply could extend to most readers today: “Oh, how I envy you! How I wish I could read my book with a fresh mind! What a wonderful experience you have in store!”