On stage, Diva D looked tiny. She weighed maybe a hundred pounds, mostly bone and made-up skin in a strapless black cocktail dress. But like most drag queens under a spotlight, she was loud. And mean. She also speaks four languages and performed weekly in what was then Jerusalem’s only gay club, the Mikveh.

“Who here’s from America?” she called out on a recent night there. “Who’s new?”

A group of thirtysomething guys in the back started laughing and pushing one among them to the front. The lucky one stepped onstage, his hair a little disheveled, a bit embarrassed to be up there. “Don’t stand so far away,” she said, pulling him by the hand toward her. “I’m not fucking Hitler.” We all laughed in the crowd. “Not that I would have fucked Hitler, mind you. That mustache!” The guy, apparently from the United States, looked toward his friends for help.

“Speaking of hair,” Diva D said, interrupting the reverie, “what’s going on with yours?” Everybody looked at his greasy shag, a little shiny under the lights. “You look like you just got off the train to Treblinka.” The guy started combing down fly-aways while I guffawed in shock. Diva D threw up her hands in mock disgust; the crowd descended into mutinous chatter. I actually heard someone behind me exclaim Oy gevalt while the Diva tried to quiet us. “I’m kidding!” she said, turning toward us with her shoulders raised and her hands turned out. “He’s not nearly thin enough.”

At this point I turned to the Israeli friend I came with, who seemed unimpressed. “I can’t believe she said that,” I said. He shrugged his shoulders. “This is nothing,” he said, taking a sip through his pink straw. “You should hear what she says in Hebrew.”

Diva D is 44 and a legend in the Israeli drag community. When I met Gallina Port des Bras—one of Israel’s most famous drag queens—she insisted that I speak with the Diva. “Diva D is the godmother of Jerusalem drag,” she said, referencing the foundational role she played in the 1990s. Diva D was also Gallina’s “drag mother,” a complex mix of professional and personal mentorship. “But she doesn’t give interviews anymore,” Gallina told me. Gallina and I have had a good experience working together, so she offered to intercede. “If I ask for you,” she said with a wink, “she’ll talk.”

Diva D, out of drag, is Dany Yair. When I arrived for the interview at the surprisingly spacious Tel Aviv apartment he shared with another performer, his immediate concern was with his dog. He opened the door, which let onto a small foyer and a very large living room. Before I said hello, his terrier started barking at me in outrage. “Don’t worry,” Dany said, petting and cooing. “He won’t hurt you.” I was unclear who he was addressing, but I decided it probably wasn’t me. This went on for at least 20 seconds, at which point I asked if I could come in. “Of course,” he said, standing abruptly. “But I don’t think he likes you.”

Off stage, Dany seemed even tinier than Diva D. He walked quietly—nearly on his toes, almost as though he were wearing heels—to the kitchen while I sank into a couch with a fine covering of dog hair. I noticed the scratching post in front of me before I realized I was sitting next to a black-and-orange cat. I decided to try my luck at another of his animals. This time: success. It was purring happily when Dany came in with a glass of Pellegrino for me and coffee for himself. “This one seems to like me,” I said, needfully.

“Oh, that one,” he said, waving his hand dismissively. “She’s a slut. She’ll let anybody touch her.”

Israel’s gay scene today is almost exclusive to Tel Aviv. It hosts the world’s second-largest annual pride parade, and it has countless bars and clubs that cater to the community. Gay tourism to Tel Aviv grows every year, and the Israeli government has even taken to promoting the city’s gay-friendly vibe. The origins of Israel’s gay-rights movement are less clear-cut than those of the United States, where the Stonewall riots in 1969 precipitated the decades-long fight for equality that is still ongoing. While some people credit the influx of American immigrants to Israel in the post-Stonewall years for the beginnings of the country’s equality movement, it’s not at all clear that this was the case. What’s more probable is that the stories and images of the American queer revolution ignited the passions of the similarly marginalized Israeli queer community. And while the developments in legal and social progress were slow to begin—homosexuality was only decriminalized in 1988—they quickly accelerated, surpassing the United States in the 1990s, at least in terms of legal rights.

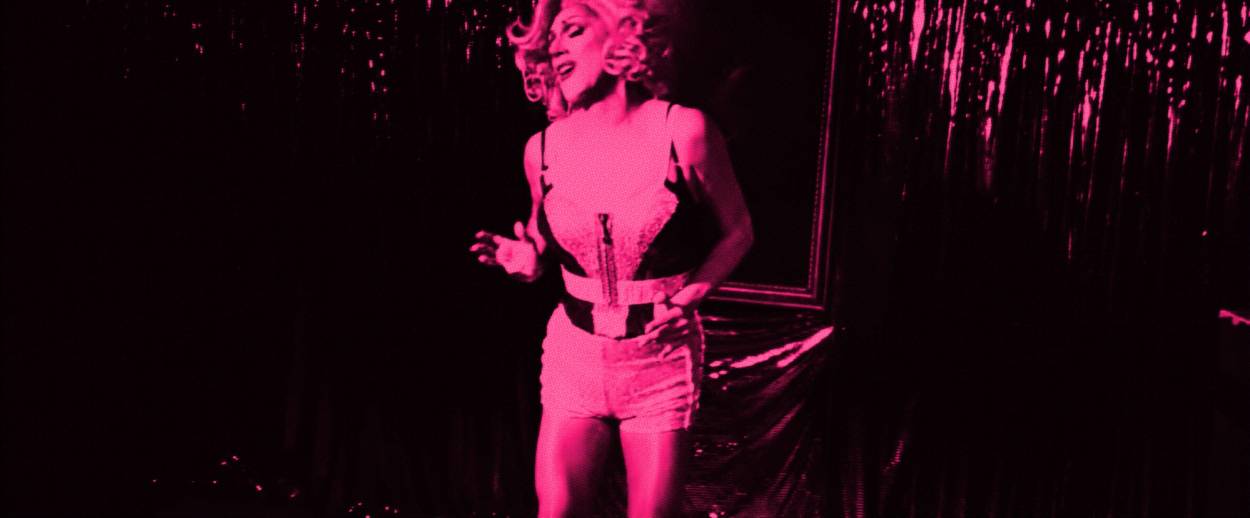

Diva D. (Photo: Nizan Bakshi & Tal Kallai)

One of the pivotal organizations in the equality march has been Aguda, Israel’s first gay and lesbian organization, which was founded in 1975. Lee Walzer, in his book Between Sodom and Eden, describes how Aguda’s allies in the Knesset—the Israeli parliament—secured a number of late-night votes in favor of gay rights, waiting for the equality movement’s opponents to go home before introducing and passing those bills into law. This, according to Liora Moriel, Aguda’s former chair, is how the law decriminalizing homosexuality was passed in 1988. This was also the tactic used in 1992, when the Knesset passed a law forbidding workplace discrimination based on sexual orientation. Other milestones of progress—including equal inheritance and immigration benefits for same-sex partners—have come at the direction of Israel’s courts.

Yet the liberalism that flowers in Tel Aviv is not necessarily characteristic of the rest of the country. The politically influential ultra-Orthodox community has, in many respects, ceded Tel Aviv to the more liberal elements of society. While there are still protests of Tel Aviv’s pride parade, the general view is “They have Tel Aviv, so let us keep Jerusalem.” The virulence of ultra-Orthodox protests against Jerusalem’s parade has led to violence and even the throwing of donkey feces—a symbol, some argue, of the “bestial” nature of homosexuality. Rabbi Ephraim Holtzberg, quoted in the Jerusalem Post while protesting in 2011, described his view of the special nature of the city: “This is not San Francisco, the capital for homosexuals. This is the Holy City, and the event is a provocation against the entire world.” Many gays and lesbians are leaving Jerusalem for Tel Aviv, quickening the pace of the Holy City’s regression. Though Dany loves his hometown immensely, he, too, has had to leave.

To begin the interview, I asked Dany about the political changes in Jerusalem in his lifetime. The question rendered him visibly agitated. It’s a subject that had preoccupied him for years, but particularly since he relocated to Tel Aviv in 2010, a move he regarded as tantamount to a military defeat. “Burqas will be in fashion next year,” he said bitterly, lighting a cigarette. “The battle for Jerusalem is on its last legs.”

One of the reasons for Dany’s continued centrality to the Jerusalem scene—aside from the Diva’s artistry—is this lexicon of militarism. For Dany, though, his role as a performer also borders on the evangelical. “Every performance I give is a political act,” he told me. “I do this for every kid out there who’s different.”

He didn’t begin his career with this intention, though. He started as one of those “different” kids, dressing up from an early age, wanting only to perform. His professional debut, as he sees it, was in 1990, when he performed on stage to the Rocky Horror Picture Show on his 19th birthday.

“I’m a classically trained singer,” he said. “At first, that’s all I knew about performing.” He stamped out the last of his cigarette with his right hand while simultaneously opening the pack for another with his left. “But that bitch choir director kicked me out.”

I asked why, given his training.

“She said I sang too loud!” he shouted. “She’d put me in the back, but I was still making too much goddamn noise,” he said, laughing.

Once he discovered drag, though, he was hooked. “At some point,” he said, motioning to a picture on the bookshelf of his early performing days, “I decided to own it. I said to myself, ‘If you’re gonna do this, you’re gonna be the freakiest bitch out there. You’re gonna be a superstar.’”

This tendency toward flash had always been a cause for conflict, particularly with his family. Although his mother was initially skeptical, she eventually came to accept and even enjoy his performances. As one always does in this country, I asked if she’s religious.

Diva D. (Photo: Nizan Bakshi & Tal Kallai)

“My mother?” he said, eyebrows raised. “I’ll tell you about her. She called me the other day, because a friend of hers that’d never been to her apartment before came over.” He took a sip of his coffee, smiling already. “The woman walks into the kitchen and sees two sinks, then turns in shock to my mother. ‘Are you keeping kosher?’ she asks.” He threw one hand down on the table, laughing. “And she says, ‘Yeah, the left sink’s for the pork and the right one’s for the shrimp!’ ”

Dany clearly loves to entertain, and it seems to be genetic. But he slipped quickly back to a serious tone as he returned to the topic of his beginnings as a drag queen. His early performances in Jerusalem, he conceded, were political, though not intentionally so. “Standing in a bar in a dress,” he said, “just down the road from the Kotel”—the Hebrew term for the Western Wall—“well, that’s a political statement.”

“But,” he added, “I was really in it for the shock value.”

That mix of ambition and provocation is still a mainstay of the Diva’s performances. Nowhere is this more evident than in her penchant to use Auschwitz in a joke at least once a night. Dany insisted this is an effective means of revitalizing a tragic but familiar narrative of orchestrated murder. But it’s also a tendency that’s native to the grieving process. “You reach a point,” he said, “where laughter feels all right. That means that you’ve come pretty far.”

What began for Dany as a hobby quickly turned into a successful career. The drag scene in Jerusalem was basically nonexistent in the early 1990s, and so Dany had no “drag mother” from whom he could learn the ropes. He turned to books and films, he said, to learn the culture and history of the genre. Torch Song Trilogy, in particular, was key. “I learned when I watched that movie,” he said, “that I was part of a larger tradition. It had a major impact on me.”

‘Every performance I give is a political act. I do this for every kid out there who’s different.’

While still a teenager, he took to living in drag full-time in the Holy City, a practice he no longer observes. I assumed this was because of harassment or violence, but he corrects me. The problem was logistical. “It was exhausting to live like that,” he said. “I’d take 45 minutes to get ready, just so I could take out the trash.”

It’s not that he wasn’t heckled in public, though. “The Haredi would shout horrible things at me,” he said, using the Hebrew term for the ultra-Orthodox. “I’d give them the finger and keep walking.” Even considering this harassment, though, he looked to the 1990s with nostalgia.

“That was the golden age for Jerusalem,” he said. “We had a bigger scene than Tel Aviv.”

Living in Jerusalem today, I am having a hard time imagining there ever having been a “golden age” of drag here, let alone one so recent. Jerusalem’s gay community today is both embattled and marginalized. The Mikveh, where Diva D performs her Monday night show—Israel’s longest-running such performance—is an important gathering place. But its owner acts with a secrecy that borders on paranoia. Performances, theme nights, drink specials—all are advertised primarily through Facebook or by word of mouth. The exception to this has been the kitschy—and cryptic—figure of the “Unibra,” a portmanteau combining the words “unicorn” and “zebra.” The design—a pink zebra head with a horn—is spray-painted on walls in some of Jerusalem’s more liberal neighborhoods with only an upcoming date below it. The curious passerby will be encouraged, the marketing theory goes, to search online for an explanation. Ultimately, this will lead to the Mikveh’s Facebook page.

This level of secrecy and vigilance extends, importantly, to the building itself. The Mikveh is located on a quiet, industrial street downtown. It’s surprisingly small. When there’s a big crowd, the effect inside can be almost claustrophobic. Outside, the bar’s entrance is remarkable only for how well it blends in: There is no sign indicating its name and no rainbow flag out front, as is the custom for most gay businesses in Tel Aviv and around the world. The club’s dilapidated appearance is indistinguishable from the surrounding storefronts, where small shops sell furniture and carpeting. The full effect is that of almost complete invisibility. This is by design.

Many businesses throughout Israel have security stationed at their entrances, but the need for further protection was highlighted by the murder of two people in 2009 at a Tel Aviv LGBT youth center. The attacker was never found, but it’s widely presumed to have been an ultra-Orthodox extremist. That the crime happened in Tel Aviv—where being openly gay is much more common—added to the sense of peril in the community. Jerusalem is a much less tolerant city, and the dance floor of the Mikveh is very compact. Secrecy is, in many ways, the only option left.

Dany sat on a couch next to mine, legs crossed and chain smoking. He was eager to talk about his life, about his role in establishing Israel’s drag scene, about his views on queer politics writ large. But he did so with an air of elegy. “I’ve fought my battles,” he said, looking out the window to the poplars shaking in the breeze. “Jerusalem is basically lost.”

Dany’s narrative of the city’s decline was unrelentingly pessimistic. Since I was living in Jerusalem, I pressed repeatedly for a ray of hope, some positive development to look to in the city’s future. He shot me down each time. “Look,” he said. “Anyone who’s even a little bit liberal is leaving.”

The primary culprit for the city’s increased conservatism is, in his mind, the rise of the ultra-Orthodox community. The Haredi population in Jerusalem has risen dramatically over the past 20 years, driven in large part by a birth rate (6 percent annually) that is much higher than that of non-Orthodox Israeli women. This population explosion has come in tandem with an increasingly active—and often hostile—movement to pressure the city at large to conform to Haredi standards of decency. The community’s protests and vandalism have rendered billboards with pictures of women largely absent from the city. (They are common elsewhere in Israel.) The increasingly frequent practice of segregating sidewalks by gender in Haredi neighborhoods has drawn a great deal of attention in secular Israeli circles lately, as has the ultra-Orthodox push to similarly segregate public buses by gender.

The real turning point for Dany, though, came in 2005, when an ultra-Orthodox man stabbed three people during Jerusalem’s annual pride parade. The man was one of a large group of Haredi protesters. The attempted murders—along with the man’s proclamation that he had come “to kill in the name of God”—revealed the true nature of the gay community’s peril in the city. Though he kept living there for several years more, the stabbings hastened Dany’s decision to move to Tel Aviv. “That’s when we said to ourselves, ‘The zealots are getting stronger,’ ” he said.

The stabbings were, in Dany’s mind, the tragic but predictable culmination of forces that had been brewing for years. Jerusalem’s first pride parade took place in 2002, and Dany, performing as Diva D, was its inaugural emcee. He played the same role the following year, at which point the ultra-Orthodox mounted a violent protest. In response, the Jerusalem Open House for Pride and Tolerance, the group that had organized the parade, changed both the route and the time for the following year. Instead of taking place at the highly visible hour of Friday at noon—just before the beginning of the Jewish Sabbath, when most people would be heading home from work—the parade was changed to take place on a Thursday night. This decision, billed as a consideration of Haredi “sensitivity” over the holiness of the Sabbath, struck Dany as an unacceptable concession. He chose to boycott the parade in protest.

“It minimized the visibility,” he said, “and thus the impact.”

The cat was now asleep on my lap. I spoke quietly, hoping to avoid waking it. I asked Dany if he had any sympathy for the desire among the parade’s organizers to appease the Haredi.

“I’m much more militant than them,” he said, almost spitting in contempt. “If you’re going to piss people off, you might as well do it in broad daylight.”

As a result of the violence, each year’s parade has been subject to tremendous international coverage. The gay community, and the organizers of the parade in particular, have responded in the way they know best: by enduring. Indeed, the parade has continued every year, and the number of participants has grown. Even Dany expects the number to keep rising each year. I asked if the increased numbers can be seen in any way as an indicator of hope.

“Definitely not,” he said, without hesitation. “They changed the time, they changed the route, they gave in to almost everything.” In response to the violence, the parade’s organizers made more drastic concessions. The 2006 parade was changed to a stadium rally, eliminating the parade portion of the event altogether. This meant no visibility in Jerusalem’s streets, a consequence that Dany viewed as a kind of further death. Only in 2012 was the original course resumed, but Dany’s sense of betrayal has been impossible to overcome.

He stood abruptly and walked to the kitchen. “I need a drink,” he said. “Do you want one?” I declined, and when he came back, I saw why he had quit giving interviews. The discussion was visibly upsetting him, not least of all because he still saw Jerusalem as his home and his life in Tel Aviv as a kind of exile. “The whole city’s been run over by them,” he said, referring to the ultra-Orthodox. “It’s an invasion. And they’re winning.”

For all the marketing of Israel as a gay Mecca, and for all its self-congratulation as the only country in the Middle East that hosts a pride parade, the true nature of daily life in Jerusalem is very different than it is in Tel Aviv. I came expecting a conservative city, no doubt, but the degree of open hostility I’ve experienced has been demoralizing and unexpected. This is not to say that I’ve experienced violence, or even explicit threats of it. But the openness of Haredi contempt is singular and afflictive, and I encounter it nearly everywhere I go in the city. It’s unlike anything I’ve experienced in my life, from small-town Mississippi, where I’m from, to large cities like Paris or London, where I’ve lived and visited. I’ve had Haredi men hiss at me as I step on the bus, while mothers pull their children toward them as I walk past in the aisle. A man once followed me for nearly 20 minutes, his face growing angrier each time I turned around. He only disappeared when I finally walked into the lobby of a police station.

Much of that scorn, I know, is tied up with my appearance. I have very long hair and rather feminine features, and this combination appears to be a bridge too far for many of the Holy City’s residents. I mention this in part to ratify Dany’s assessment of the dolorous state of affairs in Israel’s capital, for the LGBT population in general, but for the gender variant crowd in particular. But I also say this to emphasize the incomprehensibility of that “golden age,” particularly for someone who never experienced it. The main gay club of the 1990s, Dany told me, was located on one of the floors of a building at Zion Square, which is at the center of Jerusalem’s downtown. The rainbow flag flew out front, he said, visible to everyone who walked along the city’s busiest pedestrian thoroughfare, Jaffa Street. The idea of walking that street today as Dany did, in heels and a wig, seems about as wise as doing the same down a sidewalk in Biloxi.

Dany moved to a seat by the window now, calling his dog to sit on his lap. He sipped a glass of Merlot while the late-afternoon sun settled across the room. The air was thick with smoke; he hadn’t once gone more than a minute without a cigarette during the hour of our interview. He had about him the air of a banished monarch, albeit one who returned weekly to an ever-shrinking band of loyalists. In Tel Aviv he was only one member of the royal family; in Jerusalem, he was the Queen.

“Why do you keep going back to Jerusalem?” I asked.

His shoulders slumped as he dipped back into a now-familiar tone of elegy. “I can’t live there,” he said, inhaling with purpose, “but I can keep on performing.” He noted that his shows are more steeped in artistry in the Holy City than when he performs in Tel Aviv. He can expand his song choices, for example, beyond the American Top 40. He can plan more intricate choreography, too, since he knows the crowd will always be paying attention. He felt freer in Jerusalem to experiment, to keep growing as an artist, because the crowd is loyal, and he’s one of their own.

“I perform in Tel Aviv for the money,” Dany told me, “but my heart is in Jerusalem.”

I went to one more of Diva D’s performances after our interview. She was sharing the stage with Gallina, her onetime protégée who had become better known than the Diva herself. The set list was Disney songs, and the highlight an energetic duet from The Little Mermaid. The Diva, perhaps predictably, played the role of the evil squid queen, Ursula. In keeping with the international feel of the performance, the song switched at the halfway point to the Hebrew version, which I didn’t know existed. When the song ended, Gallina went backstage to change for the next number. Diva D ate up some time by moving on to her usual shtick: inviting a tourist to come onstage for some banter. The man who went up this time was less disheveled than the last, but this didn’t dampen the Diva’s in-character meanness.

“Are you Jewish?” she asked. The man smiled awkwardly and said something inaudible. “Speak into the microphone, honey,” she said, pushing it toward him.

She looked him over slowly, as though appraising his claim. She turned to the audience and raised her eyebrows. “Just be grateful I won’t ask him to prove it,” she said. “Woof.”

“Is there a reason you came to Jerusalem?” she asked.

“I don’t know,” he said, shifting from one leg to the other. “To understand my roots better, I guess.”

“Sounds like you don’t know very much,” she said. She cut the interview short and sent him back to the crowd.

“What a bore!” she said, as he politely went down the stairs to the dance floor. She called to the bartender over the microphone. “Give him a drink, on me. He needs it.” The man shuffled back toward the bar.

“On second thought,” she said, pushing back her hair in an inadvertent Cher impression, “make him pay for it.” A man beside me booed good-naturedly. The Diva turned toward the dark bar. “Hey,” she said, pointing into the dark, where she assumed the man was standing. “There’s a reason some people get turned into soap.” She pulled the microphone cord alongside her and crossed the stage.

At this the crowd erupted into an almost insurrectionary chatter. “What?” she said, raising her shoulders. “Some people can just wash the fun right out of the room.”

I laughed—unwillingly—and tried to decipher why she was still haranguing this poor man, who had probably left by now. Gallina, as it turned out, was still getting dressed backstage for the next number, so Diva D was trying to stall.

“You know,” she said, raising her hands to quiet us. “I have to tell you something.” For a moment, it seemed that Dany was speaking, rather than the Diva. “I wasn’t born a bitch,” she said. “I was made a bitch.”

Someone in the audience whooped in approval. “You get hurt,” she said, raising one hand in the air, “and then one day you decide you don’t want to be hurt anymore.”

Suddenly the room felt like a tent revival, with hands raised in the crowd and hums of approval ringing through the darkness. “But I’m in charge,” Diva D said, to more cheers. “The D in my name stands for Director.”

At that we cheered, and then the lights went down. She put the microphone away and walked backstage without another word, her heels clicking loudly in the silence.