Going to Vancouver

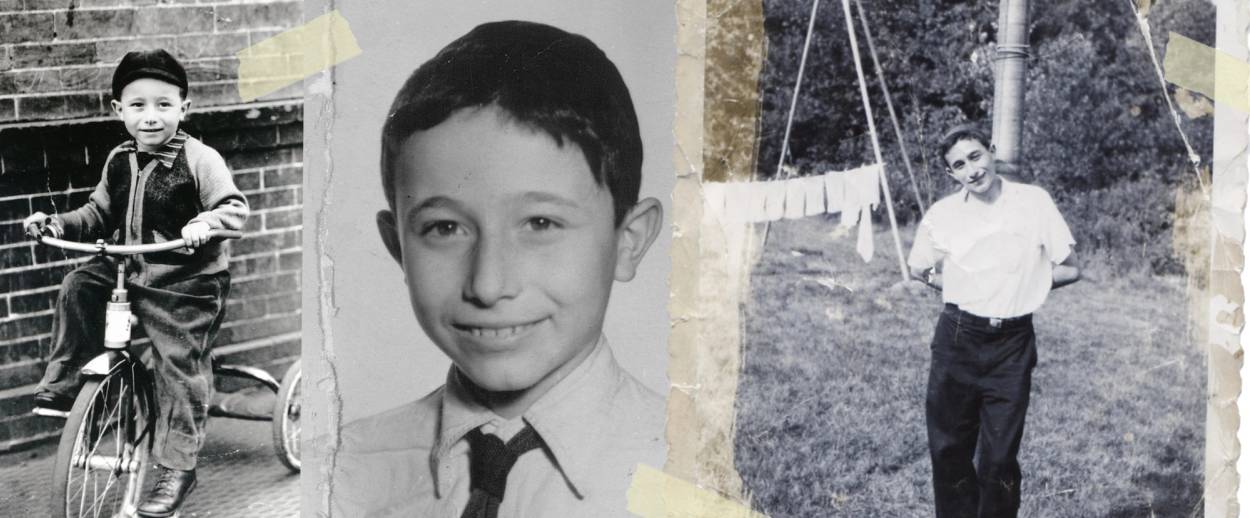

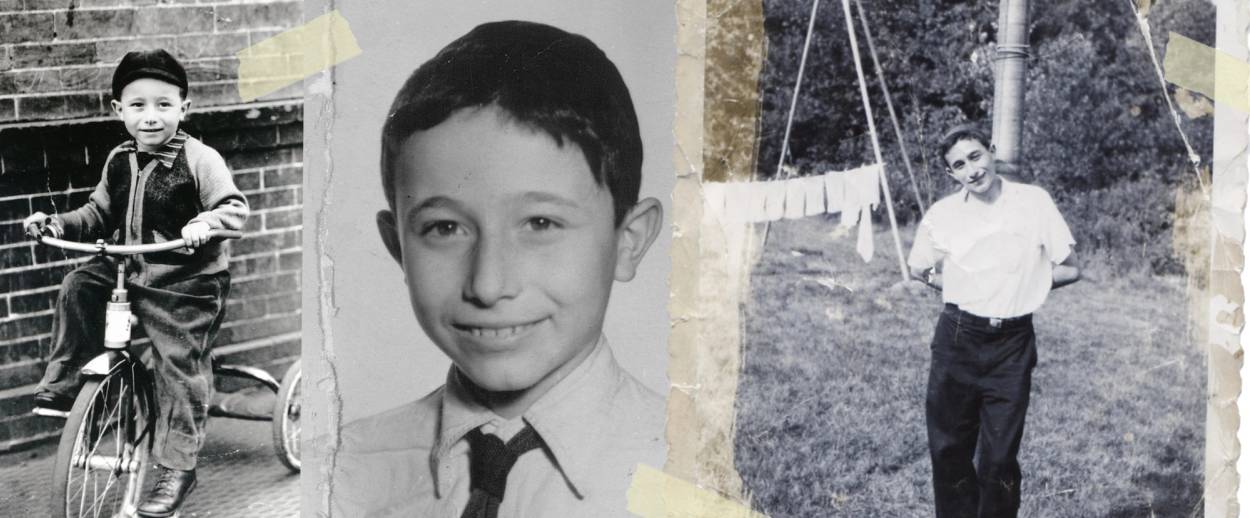

In an excerpt from ‘Meant To Be,’ the founder of the Simon Wiesenthal Center and its Museum of Tolerance remembers growing up on the Lower East Side

It has been more than 50 years since I left New York City’s Lower East Side. But that immigrant neighborhood of crowded tenements, synagogues, kosher delis, and Yiddish theaters has never left me. The people and places I first encountered on its bustling streets did not just form a backdrop to my childhood; they shaped my view of the world and my place in it. Every decision I’ve made, every project I’ve undertaken, can be traced back to those endearing characters on Cannon, Columbia, Grand, Delancey, Essex, and Henry streets.

There was our family dentist, Dr. Celnicker, who cut costs by making temporary fillings from yesterday’s newspapers. “Moishele,” he said to me one day as I looked past my scuffed saddle shoes and out the window to Clinton Street from his reclining dental chair. “Do you want me to use the sports section, or would you prefer the movie section?”

“I wouldn’t mind Joe DiMaggio’s box score!” I answered.

Across the street, the Syd and Howe Candy Store sold chocolate syrup that made the best egg creams in the neighborhood. Every Friday, cars lined up on Houston Street, trunks opened wide, waiting to be filled with two-gallon glass bottles. One afternoon as I was sipping an egg cream at the soda fountain, a Chassid barged in waving a bottle overhead. “It’s just milk and chocolate—it’s kosher, right?”

“Absolutely,” replied Joe the Fountain Man. “Just don’t drink it with a fleishig [meat] kugel.”

Harry the Pickle Man was a fixture of the neighborhood. My buddies Willie Lehrer, Sheldon Miner, and Seymour Brier and I would sometimes meet at his stall between Sherriff and Columbia streets, and tussle for the best positions around Harry’s stout wooden barrel. Convinced that the bottom of the barrel yielded the most flavorful pickles, every woman had the same request for Harry, better known by his Yiddish name, Hershele:

“Please Hershele, zei a zoy gut [be so kind] and give me nor fin hintin [only from the bottom].”

As I watched Hershele submerge each glass jar—and the sleeves of his heavy wool coat—into the dilled brine, I decided it must be the wool that gave his pickles their unique flavor.

Some of the great Jewish sages of our generation lived on the Lower East Side. Strolling down East Broadway, you might overhear your neighbor offering, “A gutten tag, Rebbe” (Have a good day, rabbi) to Rabbi Moshe Feinstein, the world-renowned Lithuanian rabbi and scholar. Or you might see a young mother waiting outside the famous Boyaner Rebbe’s shul to beseech him to say a special prayer for her sick child.

Politicians regularly made appearances in the neighborhood to garner the Jewish vote. I shook hands with Sen. Herbert Lehman and Mayor Robert Wagner on Rivington Street. The first time I saw an American president was on Delancey Street, along with some 20,000 others who shouted, “Give him hell, Harry!”

President Truman looked back and shouted, “I just tell the truth, and to them it feels like hell!”

My parents were typical Lower East Side Jewish immigrants. My father, Yankel, had set out for America in search of work to help support his mother and sisters, who remained in the small village of Jalivga, Czechoslovakia. His father, Moishe, for whom I am named, had died several years earlier, and Yankel had taken on the responsibility of providing for the family. In January 1911, he boarded the SS Poland and arrived at Ellis Island. (The name SS Poland would come to haunt him later, when Hitler’s SS murdered many members of our family in Poland.)

Like many other immigrants eager to make their way in America, Yankel officially changed his name. But brusque, American English could not convey my father’s warm, gentle manner to the people who knew him best, and “Jack” forever remained “Yankel.”

My father set an example of religious devotion tempered by humility. Each morning, en route by subway to his job as a lamp polisher at locations throughout the city, he read the Yiddish newspaper, Der Tag Morning Journal, and recited Tehillim. He refused to work on Shabbos, though the consequence was periodic unemployment. Unable to financially contribute to our shul, he fulfilled the obligation of giving tzedaka by preparing kiddush and organizing the sale of High Holiday seats. One of his favorite quotes was from the collection of Jewish ethics and advice, Pirkei Avos, “It is not for you to complete the task, but neither are you free to desist from it.”

My mother, Raisel Frost, arrived in America with her mother, Freidel, and her younger brother, Moishe, in the mid-193os. Her father, Daniel, a follower of the Belzer Rebbe, had difficulty obtaining a visa. Several years later, he and my mother’s older brother, Chuna, joined the family on Cannon Street, and Daniel went to work for Streit’s Matzo Company.

My mother, a petite 5-foot-2 brunette with piercing eyes, was as vivacious as my father was composed. She was the life of every party, with a ready and distinctive laugh. When she gossiped with her friends in the women’s balcony in shul, the cantor had no chance of being heard.

My mother was a stereotypical Jewish mother, self-sacrificing and completely devoted to her children. Every day she walked more than a mile, many times in the icy New York City winter, to bring me a fresh bagel in time for recess at the Rabbi Shlomo Kluger Yeshiva on Houston Street, where I attended elementary school, and to deliver hot cups of soup to my sisters at their public schools. After letting a salesman talk her into buying a new pair of shoes for herself when she bought me a pair for my bar mitzvah, she soon returned them, claiming they were too expensive, and that “for the few hours that the bar mitzvah takes, nobody will look to see if the mother of the bar mitzvah boy is wearing new shoes.”

Over the years, delightful stories about my mother accumulated. When she once came to Los Angeles to visit me, a man who admired her spunk asked her age. She looked him straight in the eye, and in her unmistakable Yiddish accent, retorted, “Mister, even if I would know how old I am, I wouldn’t tell you!”

Once, when we returned home from a trip and were helping my mother unpack, I discovered a small blue teapot in her luggage. “Ma, where did you get this?” I asked in surprise.

“Moishe,” she replied, “Remember when I wasn’t feeling well, and you told me to order some tea? So they sent up the tea with some honey and a little pot. I wanted to pay the man who brought it, so I asked him how much it cost. So he says twenty-one dollars. Tar a gloos vasser you vant twenty-one dollars?’ (You want twenty-one dollars for a glass of water?), I asked. But that’s what he wanted, so I paid him. After he left, I said to myself, ‘It couldn’t be twenty-one dollars for just plain water, so it must be that it includes the teapot.’ So I packed it in my suitcase.”

My parents met at one of the many social events regularly held for new arrivals on the Lower East Side. I imagine they found in each other traits they each lacked: my mother’s vitality countered my father’s calm; his dependability balanced her spontaneity. They married in 1938, and moved to a small apartment at 71 Cannon Street, where I was born on March 16, 1939. My sister, Esther, was born in 1943 and Myra followed in 1949.

While our living conditions were poor, our lives were rich. Like most Lower East Siders cramped into tiny apartments, we turned the streets around us into our living room. We visited with family, met with friends, and connected with the world-at-large by strolling down Rivington or Grand streets, or popping into Simcha Glick’s Candy Store or Sam’s Deli.

Much of our lives revolved around the Litovisker Shul, which, like dozens of other Lower East Side synagogues, provided a sense of community for hundreds of Eastern European immigrants. The shul community felt like an extended family—so much so, that men who shared the same Yiddish first names were re-named according to their physical features, like Hoycher Yakov (Tall Yakov), and Kleiner Yakov (Short Yakov), Darrer Nachum (Skinny Nachum), and Grobber Nachum (Fat Nachum) and they didn’t seem to mind.

The Hagler and Mikola families vied for dominance in shul politics. My father’s cousins, Yichel, Hersh Leib, and Mendel Hagler, were traditionalists. Each week, they sat in the same seats, and asked the same people to lead services. Mendel, Chazkel, and Hershel Mikola embraced innovation, claiming that traditional religious customs needed to be adapted to the New World. One Shabbos morning, when Yichel Hagler sent up Reb Noach, his regular choice, to lead services, Hershel Mikola reached his limit. “Yichel!” he bellowed, “Are you deaf? God Himself is pleading for us to get someone new to speak to Him!”

The Haglers were staunch supporters of the Democratic Party, and Yichel served in the powerful position of captain of the Lower East Side precinct. One Shabbos, just before Election Day, Yichel, a stocky man in his late 60s, strode to the bimah (Torah reading table) to make his usual pre-election pitch: “Ich vil dermanen yeden einem …” (I want to remind everyone) “Gedenkstalle zollen vooten far di Demecratin row B un nor row B ” (to vote only for the Democratic ticket: row B and only row B).

An angry Mendel Mikola responded, “Why haven’t you called Katz, the plumber, to fix the shul’s leaky toilets? Is it because he’s a Republican?”

Yichel’s brother, Hersh Leib, fired back, “Republicans zisten nor ouf de hoycher fensters” (Republicans only sit in high towers).

Chazkel Mikola put in his two cents: “Listen, you’ve got no business telling everyone in the shul to pull down the lever for row B. What if Hitler ran on row B?”

Realizing where this was headed, Rav Weinberger, the shul’s rabbi and a distinguished scholar, staved off the fight by issuing a rabbinic ruling. Slowly caressing the wiry white beard that concealed the edges of his face, he declared, “It is immoral to mention Hitler’s name in connection with the Democratic Party, and it is obligatory for each Jew to scrutinize the candidates before voting, just as it is required to have proper intent when performing mitzvos.” He emphatically concluded, “The toilets should be above politics, and fixed immediately.” With that, everyone charged downstairs to kiddush, where they were fortified by the herring and kugel, and continued to argue about Hitler, Katz the Plumber, and the merits of voting row B.

The Litovisker Shul had its somber moments, too. Four times a year, the recitation of yizkor, the prayer for the dead, subdued its otherwise lively atmosphere. One Yom Kippur, when I was 10 or 11, waiting outside the shul during yizkor, as was the custom for those whose parents were still alive, I noticed that the memorial service was taking a long time. When I re-entered the shul at the prayer’s conclusion, I asked my father, “Dad, why does yizkor take so long?”

For the first time, my father acknowledged a grim reality: “Moishe, many of our friends are saying yizkor for their parents and for others who were killed by the Nazis.”

“Does it take this long in Zaide’s [grandpa’s] shul, too?” I asked, hoping it didn’t, and we could go there instead.

“I’m afraid it’s the same in every shul, Moishele,” my father sadly replied.

Another passing reference to the Holocaust came from Rabbi Rosenblum, one of my teachers at Yeshiva Rabbi Shlomo Kluger, the week that Israel was created. Rabbi Rosenblum entered our classroom, as he did each morning, with a stick in one hand, and a Yiddish newspaper in the other. Before beginning our lesson in Chumash (Five Books of the Torah), he embarked on his daily ritual of briefly perusing the day’s headlines. This morning, he spent extra time scanning the paper before raising his eyes and asking, “Nu it veist vos hot parsirt heint?” (Do you know what happened?) “Mir haben a Yiddishe medina!” (We now have a Jewish state!) While wiping away tears with a handkerchief, he then mumbled, “Nein yhar tzu shpett” (Nine years too late).

Rabbi Rosenblum did not explain his reaction to the day’s astonishing news. He didn’t have to. His tears spoke louder than any speech on the subject. I inferred, as I had from my father’s yizkor remarks, that the Holocaust was a pivotal event to which an unspoken rule applied. Much like Jewish tradition approaches the study of the seminal work of Jewish mysticism, the Zohar, one should not discuss it too much, nor delve into it too deeply.

A few years later, I learned that even if I didn’t understand the Holocaust, I could glean purpose from it. I was studying for my bar mitzvah with Rav Yankele Flantzgraben, the Senior Rebbe of my elementary school, a revered Talmudic scholar, and special teacher, who made each of his students feel as if he were his only concern. One evening, while listening to me recite my Haftorah, Rav Flantzgraben interrupted me, “Moishele,” he said, “Every bar mitzvah boy has to learn something from the churban (destruction) that befell K’lal Yisroel (the whole of Israel) during the Holocaust. He can’t just get up and recite his Haftorah as if the world is the same as before, as if nothing happened to our people. Every bar mitzvah boy has an opportunity to make up for what the Nazis took from us. As the Torah teaches, `and Moshe took with him the bones of Yosef,’ so must every young man commit himself to take those ‘bones’ with him throughout his life, and replenish what was lost.”

Soon after my bar mitzvah, my parents enrolled me in the Rabbi Jacob Joseph Yeshiva (named for New York’s first and only Chief Rabbi), where I attended high school. Rav Yitzchok Tendler introduced me and a thousand other boys to the riches of Talmud study. The Talmud, we were taught, brings relevance and vitality to the Torah. The exploration of this central text, we learned, would make us part of the living history of the Jewish people—an unbroken chain of tradition, philosophy, and practice transmitted from one generation to the next.

Throughout my studies at the yeshiva, I learned many life lessons. One year, just before the festival of Shavuos, which marks the giving of the Torah, Rav Tendler shared a beautiful explanation of why a Jewish king is obligated to write two Torah scrolls. “One that he keeps in his palace, and another that he takes with him on his travels.” Rav Tendler explained, “A king, to whom subjects bow in deference, may come to believe that he is the center of the universe. Therefore, he is obligated to write an additional Torah scroll which he keeps at home in order to remind himself that he, like every other human being, has a Creator before whom he must stand in judgment.”

After school, I shed my yeshiva bocher (young student) persona, and played punch ball, basketball, and stickball with neighborhood friends, some religious, some not. I couldn’t wait to get home after a full day of studies to hang a hoop on the wall of our narrow third- floor landing and play one-on-one with my pals, Arnold Eisenberg and Leonard Sponder. In the evenings, we transformed our hallway into Madison Square Garden. Ignoring the velvet yarmulka on my head, I morphed into the Knick’s premier guard, Dick McGuire, while Arnold made the moves of the Celtic’s Bob Cousy, and Leonard pretended to be “Sweetwater” Clifton. On Sundays, we perched on the edges of seats in the Yankee Stadium bleachers, rooting for our hero, Joltin’ Joe DiMaggio.

The two worlds I inhabited rarely converged. At times, I was the exemplary child of Jewish immigrants, dutifully attending synagogue in suit and tie, enthusiastically debating Talmudic nuances. At others, I was a typical, sports-loving American kid. I never invited my nonreligious friends to join me in shul for the Simchas Torah or Purim holidays or to my home to study. I never introduced my yeshiva classmates to my neighborhood friends for fear that each side would be put off by the other.

My behavior was a reflection of the prevailing attitude in the Orthodox community of those days. Fearful of secular society and its potential to lure us away from Jewish tradition, my parents, like other religious Jewish immigrants on the Lower East Side, created an insular environment that excluded non-Jews and non-Orthodox Jews alike. As my social consciousness developed in my teenage years, I became bothered that the older generation was ignoring the fundamental Jewish teaching that “all Jews should be guarantors for one another.” My opinion grew stronger one Shabbos, when an earnest man with two young sons came to the Litovisker Shul for the first time to say kaddish (memorial prayer) for his wife, who had recently passed away. Hesitantly, he approached the shammes (sexton) to ask for a prayerbook with English transliterations. Unable to find one, the shammes recommended he go to another shul on East Broadway, about a mile away. As I overheard the brief interaction, and watched the dejected threesome leave the shul as the regulars carried on with the service, I sensed that they were headed home, alienated—perhaps forever—from the Jewish community.

I also could not understand why the Holocaust, one of the greatest tragedies in all of Jewish history, was relegated to the sidelines of Jewish communal life. I became preoccupied with the question of how the Holocaust had been allowed to happen. I found Rav Flantzgraben’s answer, “Dos iz gevein a himmel zach” (This is a matter for the heavens), insufficient.

My teenage worldview was being formed as much by movies as by Talmudic tales. Each Sunday at the Delancey, Apollo, or Palestine Theaters, I cheered the sheriffs as they rounded up posses of do-gooders to confront the outlaws, and counted on the cavalry to come to the rescue in every Indian raid. I believed that for every Jesse James there was a Wyatt Earp, a Roy Rogers, and a Gene Autry. “Where were the good guys when it came to saving the Jews?” I thought.

I wondered about the Jews themselves. Where were the Mordechais, Esthers, and Bar Kochbas among them to warn of the impending catastrophe? How could they have ignored the words spoken by Ze’ev Jabotinsky in Warsaw in September 1938?

“For three years I have been imploring you, Jews of Poland, the crown of world Jewry, appealing to you, warning you unceasingly that the catastrophe is near. My hair has turned white and I have grown old over these years, for my heart is bleeding that you, dear brothers and sisters, do not see the volcano which will soon begin to spew forth its fires of destruction. I see a horrible vision. Time is growing short for you to be spared. I know that you cannot see it, for you are troubled and confused by everyday concerns…listen to my words at this, twelfth hour. For God’s sake, let everyone save himself, so long as there is time to do so, for time is running short.”

Many years later, in 1995, my eyes would fill with tears when Israel’s most decorated soldier, Ehud Barak, would say while visiting the Auschwitz concentration camp, “We arrived here fifty years too late.” And I would react similarly when, in September 2003, Israeli pilot-officer Amir Eshel, the son of Holocaust survivors, broadcast a message as he led a formation of three F-15 Eagles on a fly-over of Auschwitz, “We pilots of the Air Force, flying in the skies above the camp of horrors, arose from the ashes of the millions of victims and shoulder their silent cries, salute their courage, and promise to be the shield of the Jewish people and its nation Israel.”

As the years passed, the Lower East Side changed. Blocks of squalid three- and four-story tenements were cleared to make way for low- income, high-rise development projects. Most Jewish families whose apartments were torn down moved to Brooklyn. The same was true for shuls and schools that had been a part of the Lower East Side’s vibrant Jewish life for more than fifty years.

My parents moved into a large public housing project on FDR Drive, a peripheral area of the neighborhood, where the majority of residents were not Jewish. Later, they relocated to the Amalgamated Co-Op Building on Grand Street to be back in the heart of what was left of the most famous Jewish community in America.

Life changed for me, too. After graduating from high school in 1956, I decided to enter the Rabbi Jacob Joseph Yeshiva’s beis medrash program. There, I would spend the next six years poring over ancient texts and debating religious law and practice in order to become a rabbi. While my friends headed off to college or went into business, I could not imagine another path for myself.

At the time, however, there was no telling what the future would hold. As I walked under the blue-grey steel beams of the Williamsburg Bridge on my way to the yeshiva each morning, I contemplated my future. I wondered how I would earn a living and support a family. Knowing my parents were unable to help me financially, I considered whether there was enough stability in the rabbinate.

As I prayed each day in front of the ark’s carved oak doors in the yeshiva’s beis medrash (study hall), I assured myself that my dilemma paled in significance compared to the challenges my parents and grandparents had faced and overcome. I knew it was wise to be practical, but I sensed that unlike previous generations, I had the opportunity to pursue the studies that challenged and nourished me. I immersed myself in the sea of the Talmud, under the guidance of some of its most learned scholars, who themselves had studied with the great Talmudic sages of pre-World War II Europe.

What a privilege it was to study in the same beis medrash as Reb Yakov Safsel, known as the Visker Iluy (Genius from Visker), one of the most accomplished scholars ever to have attended the world-renowned Slabodka Yeshiva in Poland. Whenever the yeshiva’s main study hall was crowded, I walked across the street to the small Agudas Anshei Maimed shul, where Reb Yakov sat and learned. Then in his late seventies, Reb Yakov was a diminutive man, hunched and thin. But his mind was expansive. My yeshiva friends and I would often test Reb Yakov’s memory by pretending to have forgotten a Talmudic source. Each time, completely unprepared, he precisely quoted the passage we were referencing, as if he had studied it the day before.

I developed a special relationship with Reb Yakov. On cold winter days, he liked to sip hot tea through sugar cubes he delicately positioned on his tongue. One day, to curtail the amount of sugar Reb Yakov was ingesting, Reb Chatzkel moved the sugar cube box out of his reach. Sensing Reb Yakov’s frustration, I reached up to the shelf when Reb Chatzkel left the room, rescued the box, and returned it to the amused and grateful Reb Yakov. His wink in my direction signaled that he had bestowed special status upon me.

Taking advantage of this, I decided to test the widely held belief that Reb Yakov concentrated his studies on the early Talmudic commentaries, and ignored the later ones. I selected a question posed by one of the great late commentators, and presented it, as if my own, to Reb Yakov. He quickly digested the question, and began pacing the beis medrash, deep in concentration. After several minutes, he walked toward me and declared, “Write your address on a piece of paper. When I have time, I will send you an answer.” For the next ten years, Reb Yakov sent me dozens of letters in response to my question.

Other rabbis regaled us with inspirational stories they had learned from their rabbis. Between puffs of his cherished Havana cigars, Rav Tendler recounted moments with Reb Boruch Ber, the Talmudic prodigy and head of the Kaminetz Yeshiva in Poland. Rav Tendler explained how Reb Boruch Ber never read a newspaper until Hitler came to power. Asked why he suddenly became interested in the news, Reb Boruch Ber replied, “When Jews are suffering, if I don’t know their problems, how can I advise them and share their pain?”

Rav Shumel Dovid Warshavchik recalled the last time his Rebbe, Reb Elchonon Wasserman, head of the Novardok Yeshiva, one of the world’s largest yeshivas, was in the United States. With tears in his eyes, he recounted how Reb Elchonon’s loyalty to his students cost him his life: “The Rebbe was here in New York in March of 1939, raising money for his yeshiva, when the war broke out. Many pleaded with him to stay in America and to send for his two children. But Reb Elchonon dismissed them, ‘I have four hundred children in my yeshiva. How can I leave them behind? I am a soldier, and a good soldier must go to the front.’ Reb Elchonon returned to his yeshiva, and was murdered by the Nazis two years later.”

It was in the yeshiva, where I heard the inspiring words of the distinguished Rav Yosef Shlomo Kahaneman, the former Rabbi of Ponevezh, who immigrated to Palestine after the Nazis destroyed his yeshivas and murdered his family members. He addressed us during one of his many visits to America to secure financial support for his new yeshiva in Israel. He began his remarks, “Please listen to the words of an old man, who has come here all the way from Yerushalayim, who stands before you today in this holy place to speak with you, for what I am sure is the last time in his life.” In awed silence, we listened as the Rabbi of Ponevezh implored us to do something meaningful with our lives, something that would bring honor and credit to the entire Jewish people.

In the beis medrash, Rav Mendel Kravitz, the head of our yeshiva, and the man from whom I received rabbinic ordination, often shared the teachings of his Rebbe, Rav Aharon Kotler, widely regarded as the gadol hador (greatest sage of our time). Rav Kravitz quoted Rav Aharon, who explained why the Talmud says that God judges every mortal human being three times: on Rosh Hashanah, upon his death, and just before the final resurrection of the dead. He taught that Rav Aharon understood the first two times to be logical, but pondered the need for God’s additional judgment before the resurrection. He explained that there are people whose accomplishments extend well beyond their lifespans. God suspends His final judgment to take into account the cumulative impact of each and every life in order to remind us that each person has an obligation to do good work in his generation and to plant seeds to affect future generations. God, in turn, credits such people with the residuals of their accomplishments.

I was privileged to meet Rav Aharon Kotler on two occasions during my yeshiva days. Twice, Rav Kravitz asked my chevrusa (study partner) David Greenwald and me to drive Rav Aharon from his Borough Park home to the yeshiva, where he was scheduled to deliver his annual lecture. We approached his apartment with trepidation (I had proudly displayed Reb Aharon’s Great Sages card under the glass top of my bedroom desk throughout my childhood). But when the rabbi’s wife, Rebbitzen Chana Perel Kotler, showed us into their modest apartment, with furnishings both ordinary and familiar, we felt immediately at ease. We offered to help the rabbi put on his raincoat, but the dignified Rav Aharon declined: “Ich ken iz ton a layn” (I am capable of doing it myself). People nodded toward Rav Aharon and reached out to shake his hand as we made our way to the parked car. Such a respected figure could not lead the simple private life he might have wanted.

My time in the yeshiva had its light moments. Rav Tendler once went on a hilarious rant against the increasingly popular bar mitzvah teaching aid, the tape recorder. “Boys,” he said, “You know why I am against this? I will tell you. Recently, I went to a fancy bar mitzvah of a rich man’s son. So they call the boy up to the Torah, he goes up, kisses it with his tallis, and recites the blessing, `Barchu es Hashem hamvorach.’ As is the custom, the congregation then responds, `Baruch Hashem hamvorach l’olam va’ed.’ Suddenly, the bar mitzvah boy shouts back at the congregation, ‘Shut up! I know the blessings!’ You see what happens when a tape recorder becomes a teacher,” concluded Rav Tendler.

One spring day, when we needed a break from our studies, a few friends and I decided to head south for an afternoon at the Asbury Park Amusement Center. When I managed to pop three balloons in a darts contest, I was presented with a five-foot-tall stuffed polar bear. Eager to show off the oversized prize to my sisters, I boarded a bus (paying an additional fare for the bear) then a train to Delancey Street rather than East Broadway in order to avoid the yeshiva, whose rabbis would surely frown upon my having played hooky to indulge in secular pleasures. The train pulled into the Delancey Street station, the doors opened, and I cautiously stepped onto the platform, my vision impaired by the life-size bear in front of me. As I craned my neck around the bear’s rounded ear, who should be directly facing me, but my Rebbe, Rav Warshavchik. He took one look at the bear, then at me behind it, and said with an affectionate grin, “So Moishe. This must be your chavrusa, Reb Dov Ber. One thing I can promise you, he is going to get smicha (rabbinic ordination) a lot sooner than you will!”

The Purim holiday is traditionally a time for pranks, and I was the chief prankster. At the yeshiva’s Purim party in 196o, an emcee announced to the hundreds of rabbis and students gathered, “We will begin the evening by listening to a tape recording of a recent lecture given by Rav Kotler. Following this, a student will impersonate Rav Kotler.” The emcee played the tape, and the rabbis nodded their heads in fervent agreement with Rav Kotler’s finest points, which he delivered at a rapid-fire pace, in a Yiddish dialect that was difficult to follow, even for those for whom Yiddish was a first language. When the lecture ended, the emcee announced, “I’m sorry to inform you that the young man who was supposed to come up on stage next cannot be with us. But he did not want to disappoint you, so he kindly sent us the tape you just heard.” Realizing that the rabbis had been fooled, the entire student body burst into laughter.

I was soon identified as the practical joker, who not only had imitated Rav Kotler’s distinctive speaking style, but had quoted freely from invented sources that bore no relationship whatsoever to the lecture topic. Rav Tendler was so impressed with my impersonation that he asked to borrow the tape to play for his mechutin (father of his daughter-in-law), the world-renowned Rav Moshe Feinstein. Rav Tendler later told me that Rav Moshe listened attentively to the tape, then, with a big smile across his face, quoted the verse from Genesis in which Jacob disguises himself as his brother Esau, “The voice is the voice of Jacob, but the hands are the hands of Esau.”

Like most of my friends studying in the beis medrash, I felt an obligation to ease my parents’ financial burden. Every year, I teamed up with friends to sell aravos, one of the four plant species used during the Sukkos autumn harvest festival. We left our homes at 4:oo am to catch a train to Yonkers, where the Saw Mill River empties into the Hudson, and spent the morning cutting and gathering red willow stems along the riverbank. We brought the willows in huge plastic bags to the retail market on Canal Street, where we sold them for ten cents a branch, earning a respectable five hundred to six hundred dollars each.

After three years of our annual aravos project, I hit upon an idea to improve our earnings. Since our asking price was dependent each year on how insect-bitten the leaves were, I suggested we take a few branches to the Bronx Botanical Garden to see if the experts could help us figure out what to do about the bugs.

Off we went to the botanical garden, where a botanist identified our willow as salix pulpurea, and, intrigued by our description of the Jewish tradition of shaking it each day of Sukkos, suggested we have a professional nursery grow them. He made a few phone calls, then provided us with contact information for a nursery in Princeton, NJ.

The next day, Fishel “Pepsi” Hochbaum, Max Kaminetzki, and I negotiated a deal with the Princeton nursery to grow fifteen thousand aravos for the following year. Over the next few years, we steadily increased the order, until we reached two hundred thousand branches annually. We paid the nursery four cents per stem, and sold them for ten. While our profit margin was reduced from our first years, our volume was dramatically increased, bringing our net individual incomes to a stunning four thousand dollars—and we no longer needed to wake at 4:00 am to catch the train to Yonkers.

Our entrepreneurship enabled us to forge special relationships with the gabbais (rabbis’ assistants) who ordered aravos for the major Chassidic sects in New York. Reb Yossel Ashkanazi, the gabbai of the Satmar Rebbe, was so impressed with the quality of our aravos that he ordered twenty five thousand units and invited us to the Rebbe’s home so the Rebbe could give us a blessing.

Almost overnight, a few yeshiva boys from the Lower East Side had become aravos moguls. But our dominance of the market did not last long. Two years later, I received a terse call from my partners informing me that I would no longer be receiving my usual share of the profits. Apparently, we had been out-foxed by our long-time competitors, the Buxbaum brothers, who spotted our trailer’s NJ license plates, and honed in on our supplier, to whom they offered more money and signed an exclusive five-year contract. While the incident brought to an end any aspirations I might have had to become a businessman, I nonetheless took pride in knowing that along with my yeshiva buddies and the botanist from the Bronx Botanical Garden, I had changed the way aravos are grown and sold in America.

No resume of a young man from the Lower East Side would be complete without a stint in the Catskills. My gig was as busboy, then waiter, at the West End Country Club in Loch Sheldrake. The West End was an ideal escape from New York City’s steamy summers for hundreds of middle-class Orthodox Jewish families. The resort had all they needed: a shul, a pool, and Jerry Lewis, just up the road at the posh Brown’s Hotel.

Food was the main attraction in the Borscht Belt, where guests lined up outside the hotel’s vast dining halls a half-hour before they opened, three times a day. One afternoon, waiting near the kitchen to pick up an entree for a guest, I noticed the hotel’s co-owner, Izzy Leibowitz, mixing his famous spring salad, elbow-deep in cottage cheese. Ever frugal, Izzy slid the leftover cottage cheese down his hairy forearms into a plastic vat. When I returned to the dining room, a hefty woman with a thick Brooklyn accent assailed me: “What did I tell you when we checked in? We have been coming here for ten years, and whenever they serve spring salad we expect seconds, because it’s a Leibowitz special.”

I quickly apologized, delivered another portion, and concurred, “You are absolutely right, Ma’am. The West End spring salad certainly is an Izzy Leibowitz special.”

While life as a waiter meant long work hours, little sleep, and even less pay, adequate compensation came in the form of socializing. At the West End, I met an assortment of people I never would have encountered at the Rabbi Jacob Joseph Yeshiva. On Saturday and Sunday nights, I listened to guest entertainers singing popular American and Israeli songs. And at the West End, I met my life’s partner.

During our daily, two-hour break between lunch and dinner, I often played ping pong with Adele Mermelstein, who came to the hotel each summer from Borough Park with her husband, Sol, who had survived Auschwitz, and their two children. During one of our matches in the summer of 1961, when she was clobbering me with her superior serve, Adele matter-of-factly said, “I’d like you to meet my younger sister. She’s a counselor here. She’s very smart and good looking.” She did not need to add another word. I knew that everyone admired the Mermelsteins and I knew that I was a sheltered young man who lacked the confidence to initiate a conversation with a young woman.

The next day, Adele introduced me to Marlene, known affectionately as Mande, and her parents, Hanna and Harry Levine. As advertised, she was intelligent and attractive. We had many complementary traits: she liked to laugh, and I liked to tell stories; she loved cookies and I was in a unique position to supply them. We saw each other many times that summer, and when the season sadly drew to a close, she extended the pleasure it had brought by accepting my offer of a date when we returned to the city.

Once back at the yeshiva, however, I realized I was in a predicament. In those days, no young woman would consider seriously dating a young man who had no idea how he was going to support a family. I continued on in my studies, indefinitely postponing a date with Malkie, although we spoke often on the phone.

Then, one December day, Rabbi Bernard Goldenberg, the senior rabbi of Congregation Schara Tzedeck in Vancouver, Canada visited my yeshiva to seek recommendations for filling the position of Assistant Rabbi. I typically spent my days studying with other rabbinical students in the Agudas Anshe Maimed Shul. But that day, when we discovered that the shul’s heater was broken, we relocated to the main yeshiva building. Much to my surprise, and perhaps only because I was seated nearby, Rav Warshavchik called me over to introduce me to Rabbi Goldenberg. We spent the afternoon discussing the Vancouver position, and by the end of the day, Rabbi Goldenberg made me an offer. The Yiddish words my beloved grandmother, Freidel, regularly repeated to me rang in my ears: “Alles in leben iz barshert” (Everything in life is meant to be).

Excited and emboldened by my new job offer, I made arrangements to take Malkie on our first formal date. Our dinner at Manhattan’s famous Lou G. Siegel’s restaurant was memorable, both because Malkie was impressed that Rabbi Goldenberg had offered me the position from a large pool of qualified candidates, and because I didn’t bring enough money to pay the bill. I had done the math while savoring the delicious flanken, and realized I was about to come up short. Embarrassed and desperate, I scanned the restaurant for someone from whom I might borrow money, stalled by telling Malkie every story I knew, and prayed for a miracle. When the waiter presented me with the bill, Malkie unexpectedly came to the rescue. “Will twenty dollars do it?” she asked. My granddaughter, Rachel, would later tell me that that moment marked the beginning of my fundraising career.

A few months later, I was ordained as a rabbi, and asked Malkie to marry me. I used the money I had saved from the aravos business to buy her an engagement ring. We were married on September 8, 1962 at the Riverside Plaza Hotel in Manhattan. We celebrated with our parents, Malkie’s grandmother, Kayla, and my grandmother, Freidel, all of whom had sacrificed so much for us. I danced with Rav Yankele Flantzgraben, Rav Yitzchok Tendler, Rav Shmuel Dovid Warshavchik, Rav Mendel Kravitz and the other rabbis with whom I had studied, and my friends, Dovid Greenwald, Heshie Weinreb, Shobsie Knobel, Leibeish Topp, Yakov Goldberg, Alan Press, Sheppie Borgen, Shimshon Bienenfeld, Fishel Hochbaum, Dr. Jerry Hochbaum, Max Kaminetzki, and Harvey Hoenig with whom I spent my unforgettable formative years.

But the day was bittersweet. Malkie and I knew that in just one week, following the traditional sheva brachos celebrations, we would be leaving the Lower East Side and Borough Park, the only worlds each of us had ever known. As we said our final goodbyes to family and friends after the wedding, my father shared one last story from the Litovisker Shul that lightened the mood.

“Moishe,” he said, “Everyone in the shul is worried about you. I asked them what they are worried about, and they told me I must be crazy to let my son go off to a Communist country to be a rabbi. Rabbi Horowitz himself said to me, “Er nemt a shtellar by Castro. Dorten hast min yidden!” (He’s taking a position with Castro. They hate Jews there!) “Dad,” I replied, “You have nothing to worry about. I’m not going to Vancuba, I’m going to Vancouver!”

Excerpted with permission from Meant To Be, by Rabbi Marvin Hier. Copyright © 2015 Marvin Hier.

Rabbi Marvin Hier is the founder and dean of the Simon Wiesenthal Center, its Museum of Tolerance, and of Moriah, the Center’s film division.