Golden Link

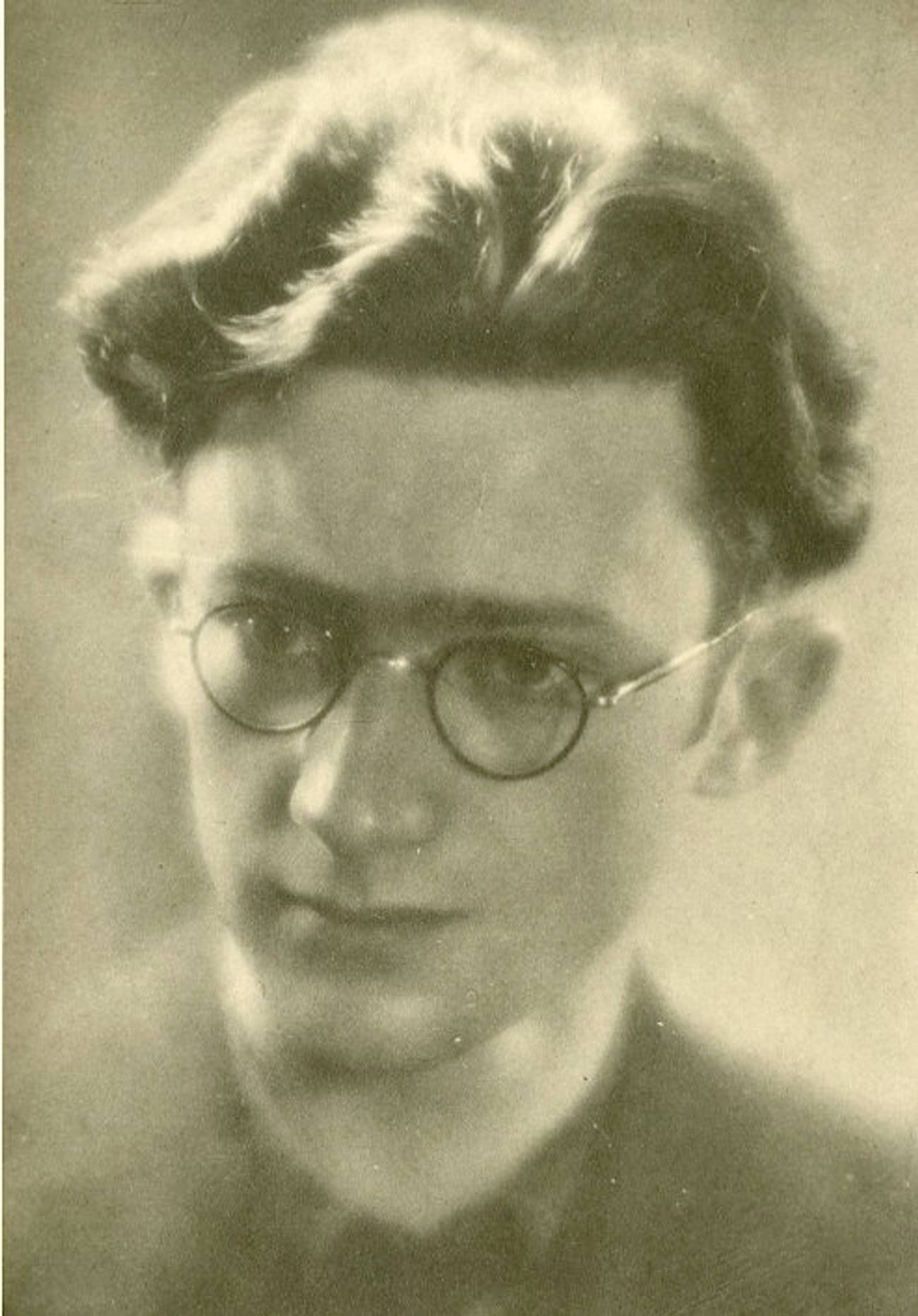

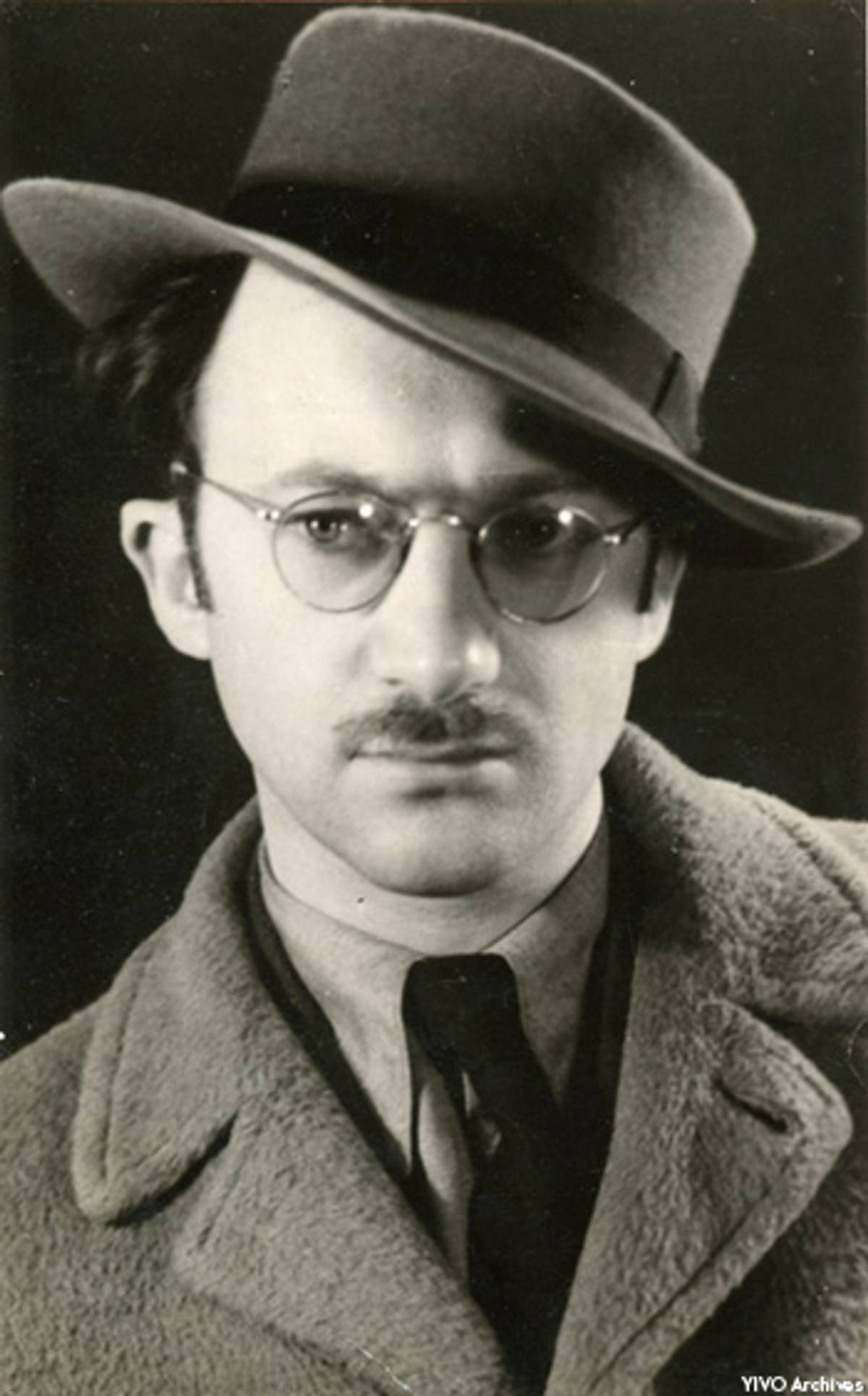

The epic life of Yiddish poet Avrom Sutzkever, who died last week at 96

Avrom Sutzkever, the Yiddish-language poet who died January 20 at the age of 96, lived the tragedies and glories of modern Eastern European Jewish culture. He had his start as part of the Young Vilna literary movement and melted lead type into bullets in the Vilna Ghetto, from which he helped save Jewish cultural treasures, including his own manuscripts. His mother and young son were killed in the Holocaust. After the war, he was a witness at Nuremberg, and later—already a world-renowned poet—he came to Israel, where he was at the center of the Yiddish literary community and founded and edited the greatest Yiddish literary journal, Di Goldene Keyt, until its final issue, in 1995.

But if we dwell on merely the biographical details of the man, we are in danger of overlooking the importance of his work, which is indebted to Sutzkever’s epic life but also independent of it. Sutzkever’s work was outside the boundaries of school or ideology while benefiting from many of them. Like Marc Chagall, he was a virtuoso of the fiddle, the rose, the dove, and the rain, which in his hands became not cliches but inexhaustible possibilities. Even when the wellsprings of Yiddish culture dried up and it became ever narrower, Sutzkever found new depth in his craft, as if following his own map to buried meaning.

Indeed, the Jew who looks to literature for guidance in this polarized age would benefit from Sutzkever’s work, which is born of history but is unfettered by it. While many today are focused on particular kinds of Jewish space and time—Israel, the synagogue, the Sabbath—Sutzkever built and inhabited his own realms, which developed according to their own extrahistorical laws. When Sutzkever wrote about melting the lead plates of the Rom publishing house into partisan bullets, he likened the resulting foundry to the temple where Jewish elders poured oil for the menorah. The word he used—templ— is rarely used in Yiddish, as opposed to the familiar Hebrew term beys-hamikdesh. But his use of the word changed. The next time he used templ, in the 1955 long poem “Ode to the Dove,” was not as a reference to the Temple in Jerusalem, but his own personal structure:

Boyen un boyen dem templ, mit zunikn seykhl im boyen!

Building and building the temple—built with a mind like the sun!

Like every other Yiddish writer, he was forced to find a life for his postwar work after the mass death of the Holocaust. But while other writers perseverated on the world that was lost—which for many led to artistic stasis—Sutzkever built new worlds in lyric self-expression. Yes, he wrote about ghetto existence, and about life in hiding while the Nazis raged, but those were his Holocaust-era works, not signposts to an unchanging style. Historical moments were for him the raw material for his own poetic vision, not excuses for occasional verse.

It came early, this habit of being in the world historically but separate from it poetically. The Vilna of his youth—like the rest of Jewish Eastern Europe—was riven by political rivalries. Many poets either retreated to a prickly and hostile Modernism or stood on the battlements of their chosen political castle, lobbing poetry at their opponents. Sutzkever flirted with Modernism, but he was never married to it. From his very earliest poems, he saw himself as the poet-prophet whose mission was to inscribe the hidden story of the earth.

Such prophetic poetry is not reader-friendly. It is full of words that are hard to understand even for the fluent Yiddish speaker. It mines a hyperliterary Yiddish that no one uses anymore and that precious few ever did. Its conclusions are not clear, and its images rarely easily parsed or comfortingly sentimental. This makes it even less likely, unfortunately, that anyone will read his work now. In Sutzkever’s words, “Who will be left?”

Sutzkever’s personal postwar existence was in Israel, of course, where he chose to make his home; he was a committed Zionist of the socialist variety (his journal was funded by the Histadrut). But despite being awarded the Israel Prize in 1985, he never garnered the glory he deserved. Israel woke too late to the language and culture whose disappearance was partially due to anti-Yiddish sentiment that the young nation had actively fomented. And, on the other end of the Jewish axis, Sutzkever has never been widely read or appreciated by American Jews, who have ignored Yiddish high literary culture.

But with the fires of the Holocaust at his back and his face to a new Israel, Sutzkever had his poetic vision trained on a temple of the intellect that only a poet could build. Shelley said that poets were the unacknowledged legislators of the human race. Avrom Sutzkever was a lyric prophet insufficiently acknowledged in his own time. Perhaps, though too late, this can be redressed.

Zackary Sholem Berger is a Yiddish- and English-language poet and translator living in Baltimore.