Gospel Music’s Jewish Genius

The Fan Who Knew Too Much collects Anthony Heilbut’s essays on politics, culture, and gospel music

One night during Hanukkah in 1961, a special guest arrived at the Forest Hills apartment of two German Jewish refugees named Otto and Bertha Heilbut. She was Marion Williams, one of the foremost gospel singers in American history, who was in New York to perform in Langston Hughes’ Christmas musical Black Nativity. At one point during dinner, Mrs. Heilbut whispered into Williams’ ear and the guest slipped briefly into the bathroom. She emerged smiling, having removed her girdle at her hostess’s knowing invitation.

As the evening progressed Mr. Heilbut sang a few Hebrew songs, more somber than celebratory, more a testament to his uprooted life and slain relatives than to the triumphal holiday. Then he turned to Williams and asked, in his impeccable yekke manners, “Perhaps you would like to sing some hymns.” And there in the Heilbut apartment, she launched into “Touch Not My Anointed,” a gospel classic drawn from verses in 1 Chronicles and Psalms. From that night on, for decades to come, Williams would always refer to Bertha Heilbut as “my Jewish mother.”

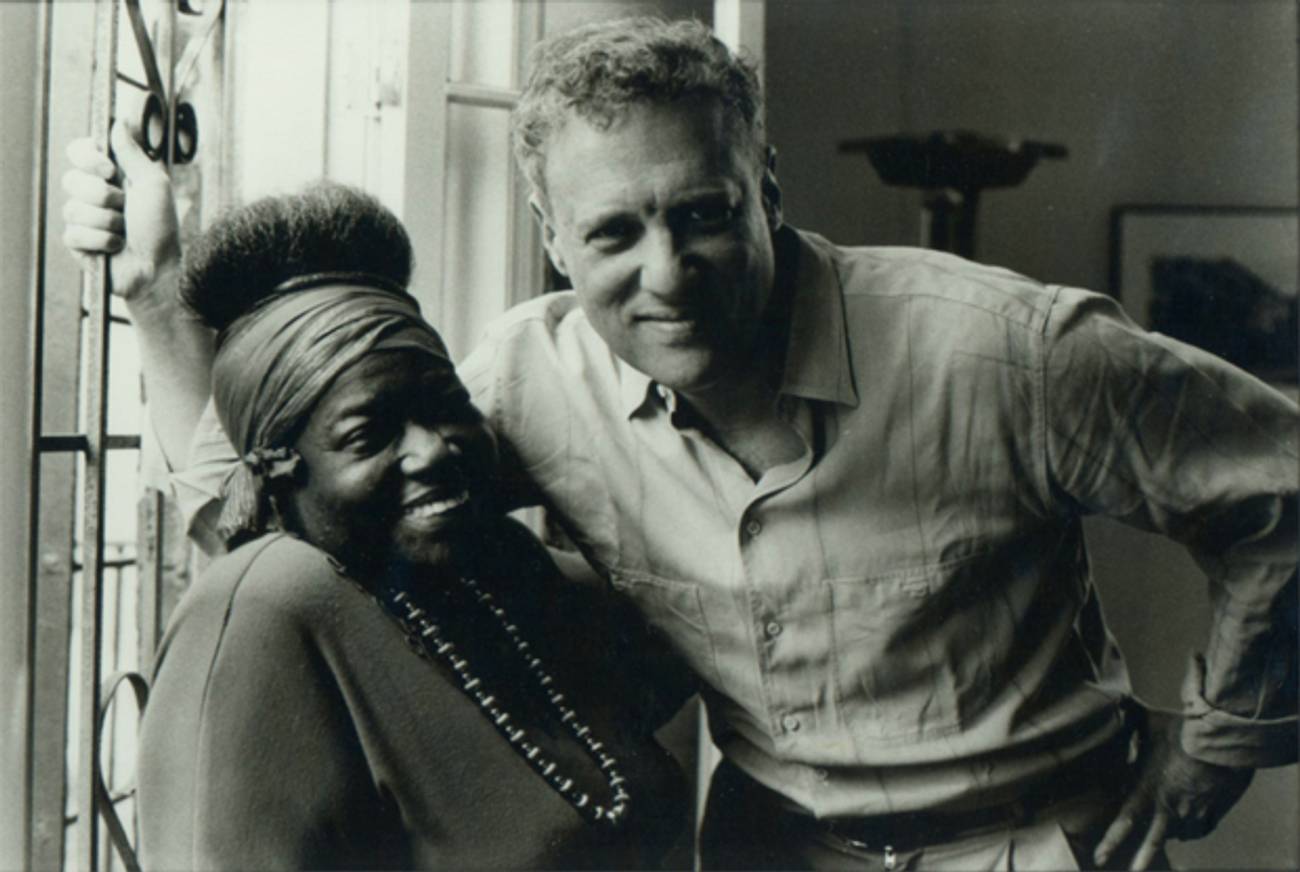

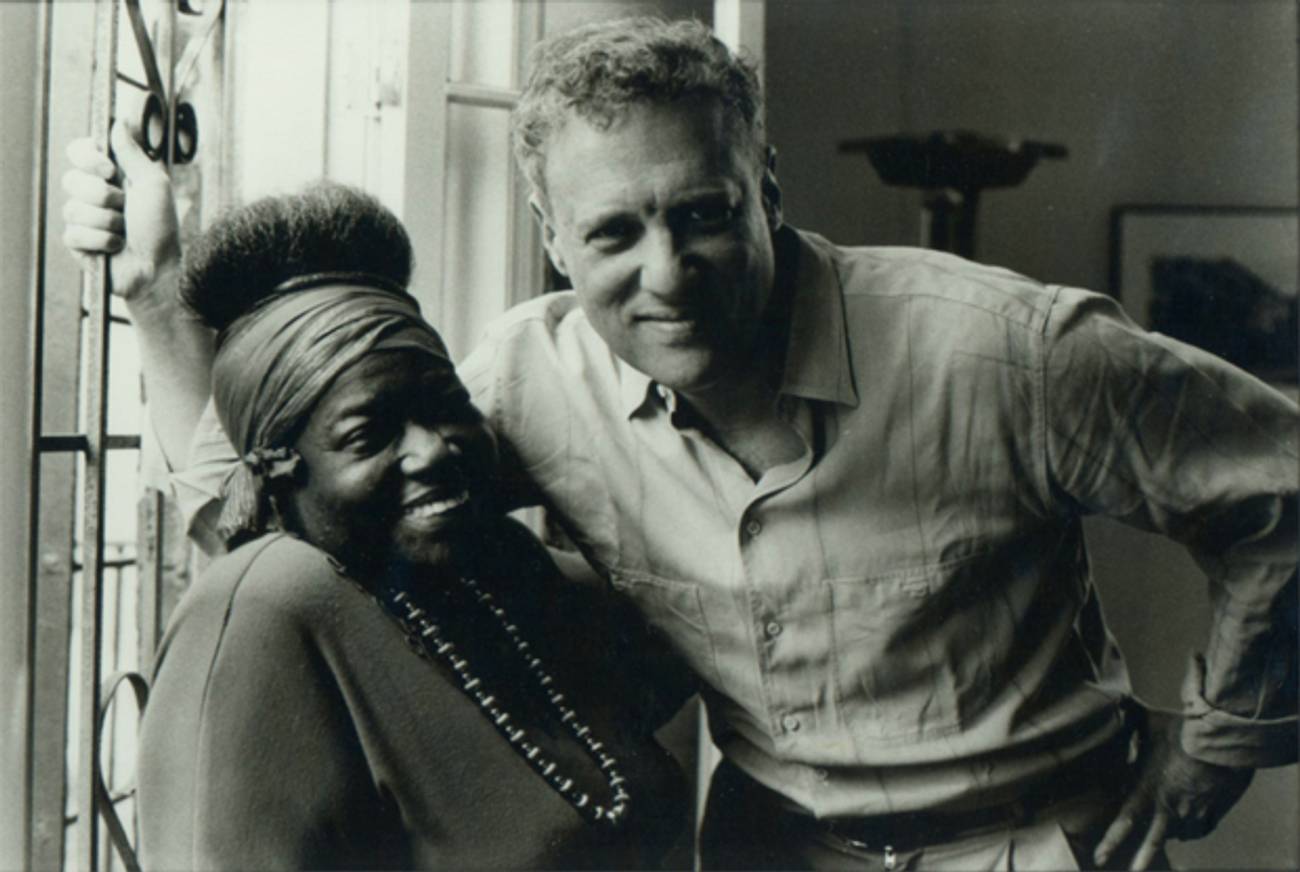

The entire unlikely episode only happened, though, because of the Heilbuts’ eldest son, Anthony, a college student at that time and a regular attendee of gospel shows at Harlem’s Apollo Theater. The Hanukkah dinner, as much as any moment in Anthony Heilbut’s life, anticipated his ultimate role as gospel’s Jewish genius. Over more than a half-century of immersion in the gospel world, Heilbut has written the definitive book on the music, The Gospel Sound, has produced albums that have earned both national and international awards, and been the friend, collaborator, and confidante of many of the finest gospel artists, including Mahalia Jackson, Alex Bradford, and Sister Rosetta Tharpe.

This week, Knopf published a Heilbut anthology that covers many of his trademark subjects. Fittingly titled The Fan Who Knew Too Much, the collection of essays deals with gospel music, German Jewish emigrés, soap opera, blues, and the gay experience. What might seem on first inspection to be a miscellany is on deeper reading a kind of artistic autobiography, one that traces Heilbut’s path from a childhood among the displaced and dispossessed to a lonely adolescence fixated on soaps to an emerging maturity in which gospel, literature, and gay identity each gave his life meaningful definition.

“I am a weird combination,” Heilbut, now 71, says of his boundary-crossing role. “I’m a gay man with strong heterosexual tendencies. I’m a lefty who doesn’t trust the plebs. And I’m an atheist who loves gospel music.” More than that, he is an atheist of a very particular sort, one whose parents barely escaped the Holocaust and one who grew up knowledgeable about the Judaism he ultimately chose not to practice. Yet in ways that even the loquacious and eloquent Heilbut cannot always articulate, his specific Jewish identity prepared the soil of his soul for gospel’s music of spiritual transcendence and political liberation.

***

Anthony Heilbut’s parents embodied the lesson of Nazi Germany: Every Jew, no matter how wealthy or well-connected, was vulnerable. Otto Heilbut, the grandson of the chief rabbi of the British Empire, helped run his extended family’s elite department store, N. Israel. With his resources, he donated money to the Zionist movement and relief for Jewish refugees in Eastern Europe. Bertha was blond enough to pass for gentile. During Kristallnacht, however, the N. Israel store was destroyed. Bertha began hiding Jews in the family’s vast apartment. Thanks to the combination of a cousin’s British papers and the Dutch passport Otto held thanks to his birth in Holland, he and Bertha were able to leave Berlin in 1939. By then Bertha’s disabled brother had already been interned by the Nazis. Otto’s nephew and two nieces, unable to flee Germany, died in the Holocaust.

When the Heilbuts reached America in 1940, and even more so after the war’s end, their destinies diverged. Otto, the Berlin aristocrat, was reduced to hustling as a textile broker, and his brokenness was visible to Anthony from an early age. Bertha, almost 20 years younger than her husband, went to college to become a social worker, with Anthony sometimes writing her term papers. She ultimately developed a specialty in interracial adoption.

A proud nonbeliever, Bertha nonetheless listened to the radio broadcast of Friday night services from Temple Emanuel on Fifth Avenue, the virtual cathedral of classic German Jewish Reform. With their more modest means, the Heilbuts belonged to Congregation Habonim, a Reform temple in Queens. Otto presided over a kosher home and accepted Anthony’s explanation that the lobster and crab he sometimes snuck into the house was “flounder.” On the High Holy Days, the Heilbuts brought Anthony and his younger brother to Town Hall for services, and during yizkor the Holocaust survivors wailed at the intoning of the necrology. In retrospect, Heilbut says now, those moments prepared him for the high emotions of gospel concerts.

There was plenty of cantorial music in the Heilbut home and the Habonim synagogue, but not of the genuinely operatic sort that might have made Anthony an adherent. Instead, he began to discover rock ’n’ roll on the radio show hosted by “Moondog,” the on-air handle of Alan Freed. The search for live shows brought Heilbut, at age 14, to the Apollo for the first time, and his parents permitted his racial and musical explorations. Sometime in 1957, Heilbut wound up watching a double-bill of Mahalia Jackson and the Pilgrim Travelers and his life changed.

“The shows I saw at the Apollo—Fats Domino, Big Maybelle, the Clovers, the Drifters—were fun, but the gospel shows were a whole other ballpark,” Heilbut recalls. “You have songs that could sometimes last half an hour. At the gospel shows, they’d have these nurses on either side of the stage. I asked why and was told, ‘Some people may faint.’ I’d seen kids scream for Jackie Wilson, but this—it was far beyond anything I’d seen.”

But there was also a political dimension to Heilbut’s enthusiasm. Having endured and barely survived the Nazi version of racial supremacy, Otto and Bertha Heilbut “had huge sympathy for the treatment of black people in America,” Anthony remembers. “It was very easy for them to make links between that and the treatment of Jews in Germany.” As a 16-year-old freshman, Anthony joined the Queens College chapter of the NAACP and began booking gospel concerts. “They were bringing in all these folksingers,” he recalls, “and I said, ‘Shit, let’s bring in the music black people listen to.’ ”

On the other side of the racial border, Heilbut benefited from a common perception among blacks that being Jewish wasn’t the same as being white. It took the television miniseries Holocaust, which was broadcast in 1978, to educate his closest friends in gospel about the details of the Jewish tragedy. After watching the show, Marion Williams and Dorothy Love Coates sheepishly told Heilbut, “We never knew.” He says now of that encounter, “They had no idea I was German Jewish and this could’ve been my family killed. They simply saw this as the Jewish apocalypse.”

As for gospel as religious music, Heilbut insists that he never felt the spirit move him. “I love gospel music without believing a word of it, at least anything beyond the sense of triumphing over impossible conditions,” he writes in The Fan Who Knew Too Much. Yet an anecdote he recounts in the book suggests at least a few cracks in the rationalist edifice. On the day when Marion Williams introduced Heilbut to Sister Rosetta Tharpe, another of gospel’s matriarchs, she assumed that the white boy would want to hear about her up-tempo songs, ones that were essentially rhythm and blues. Instead, he kept steering her back to “her earliest, saddest housewreckers.” Tharpe turned to Williams and said, “This child ain’t right. He likes all those deep songs.” Williams responded, “He say he an atheist and he only go for those hard songs, the kind that make you bust a gut.”

For whatever complex interplay of reasons, Heilbut plunged deeper into gospel music as he took numerous courses in sociology and anthropology while majoring in English at Quenns College and then earned a doctorate in English literature at Harvard. He ghost-wrote some gospel reviews for music magazines and did his first liner notes, for God and Me by Marion Williams and the Stars of Faith, in 1962. The following year, he was audacious enough to approach John Hammond, the legendary producer for Columbia Records, with a proposal for an album of gospel songs associated with the civil rights movement. Too radical, Hammond answered.

The crossed wires of Heilbut’s passions finally paid off in the late 1960s. His mentor at Queens College, a professor named Mariam Slater, introduced him to Maya Angelou. She, in turn, introduced Heilbut to Robert Loomis, an editor at Random House. And while Loomis was unable to get internal support for Heilbut’s prospective book about gospel music, he sent the would-be author on to Michael Korda at Simon & Schuster, who made the deal. With his advance, Heilbut traveled to Chicago for the first time so he could interview gospel’s stars in what was for many of them their home city.

When The Gospel Sound was published in 1971, it made an argument that had rarely been expressed in such length and detail: that the black church was central to American pop music of any color, as well as to the political climate surrounding civil rights, the anti-Vietnam War movement, and the counterculture. “All rock’s most resilient features, the beat, the drama, the group vibrations derive from gospel,” Heilbut wrote at the time. “From rock symphonies to detergent commercials, from Aretha Franklin’s pyrotechnique to the Jacksons’ harmonics, gospel has simply reformed our listening expectations. The very tension between beats, the climax we anticipate almost subliminally is straight out of the church. The dance steps that ushered in a new physical freedom were copied from the shout, the holy dance of ‘victory.’ The sit-ins soothed by hymns, the freedom marches powered by shouts, the ‘brother and sister’ fraternity of revolution: the gospel church gave us all of these.”

The Gospel Sound made enough of an impact, commercially and critically, to be updated and reissued in 1975, 1985, and 1997. As importantly, the book set Heilbut on a parallel career as a gospel music producer. Starting with two anthologies of songs and artists from The Gospel Sound, he went on to produce more than 50 albums and to launch his own label, Spirit Feel. His albums have won a Grammy (for Mahalia Jackson’s “How I Got Over”) and a Grand Prix du Disque (Marion Williams’ “Prayer Changes Things”) and been chosen for the Library of Congress’ National Registry (Precious Lord: The Gospel Songs of Thomas A. Dorsey). He also has written liner notes to more than 80 gospel albums.

As the decades passed, however, Heilbut came to feel disenchanted with the direction of gospel. He located the music’s golden age in the years from 1945 through 1960, the era of Williams, Coates, Jackson, Tharpe, Clara Ward, James Cleveland, and Alex Bradford—the years when future pop stars like Lou Rawls and Sam Cooke were still singing in gospel quartets. From the 1970s onward, gospel increasingly took on the sonic trappings of light jazz in the hands of popular groups like the Winans. The vocal device of melisma, so effective when used in moderation, became a cliché, the cheap trick of contestants on American Idol. Heilbut dismissed it as “the gospel gargle.”

Meanwhile the black church, as an institution, palpably split between factions committed to its tradition of liberation theology and to an emergent “Prosperity Gospel” typified by the megachurches led by such pastors as T.D. Jakes, Eddie Long, and the appropriately surnamed Creflo Dollar. As a gay man, Heilbut grew privately indignant at the homophobia that many black churches—including some that were progressive on other issues—expressed during the AIDS epidemic and later in the national debate over same-sex marriage.

The Fan Who Knew Too Much arrives, then, as a kind of bittersweet valedictory. Its most urgent essay, “The Children and Their Secret Closet,” tells about a side of gospel music that Heilbut had known well for decades but never felt free revealing: the prevalence of gay, lesbian, and bisexual musicians. In part, he was freed to out them because so many—Bradford, Cleveland, Tharpe, Ward—had died. “With the few singers left—I’m old and they’re ancient—I felt I could say these things,” Heilbut explains. He also wrote out of a j’accuse impulse, because he considered it unconscionable for so many black ministers and so much black laity to have voted against same-sex marriage measures in California, among other states.

“Everyone understood that gospel depended on the labor and talent of its gay practitioners,” Heilbut writes. “If everything wasn’t spoken aloud, it didn’t always need to be; Don’t Ask Don’t Tell has rarely been so painless. But that has changed. The family secret has become public knowledge, and the black church, once the very model of freedom and civil rights, has acquired a new image, as the citadel of intolerance.”

In one sense, the passage of time is working to Heilbut’s advantage. President Barack Obama’s recent endorsement of same-sex marriage has moved black opinion on it from strongly opposed to moderately favorable, according to a recent poll in Maryland. Musically, however, Heilbut accepts the reality that his taste in classic gospel brands him a “moldy fig,” a venerable disparagement from the bebop jazz scene. “I’m more impressed by what I’ve heard in recent Jewish choral music than current gospel,” he says. “There’s stuff being done by what my father would call ‘Our People,’ that if I want to get started all over again in my seventies …”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Samuel G. Freedman is a journalism professor at Columbia University and a regular contributor to Tablet. He also writes the “On Religion” column for The New York Times.

Samuel G. Freedman is a journalism professor at Columbia University and a regular contributor to Tablet. He also writes the “On Religion” column for The New York Times.