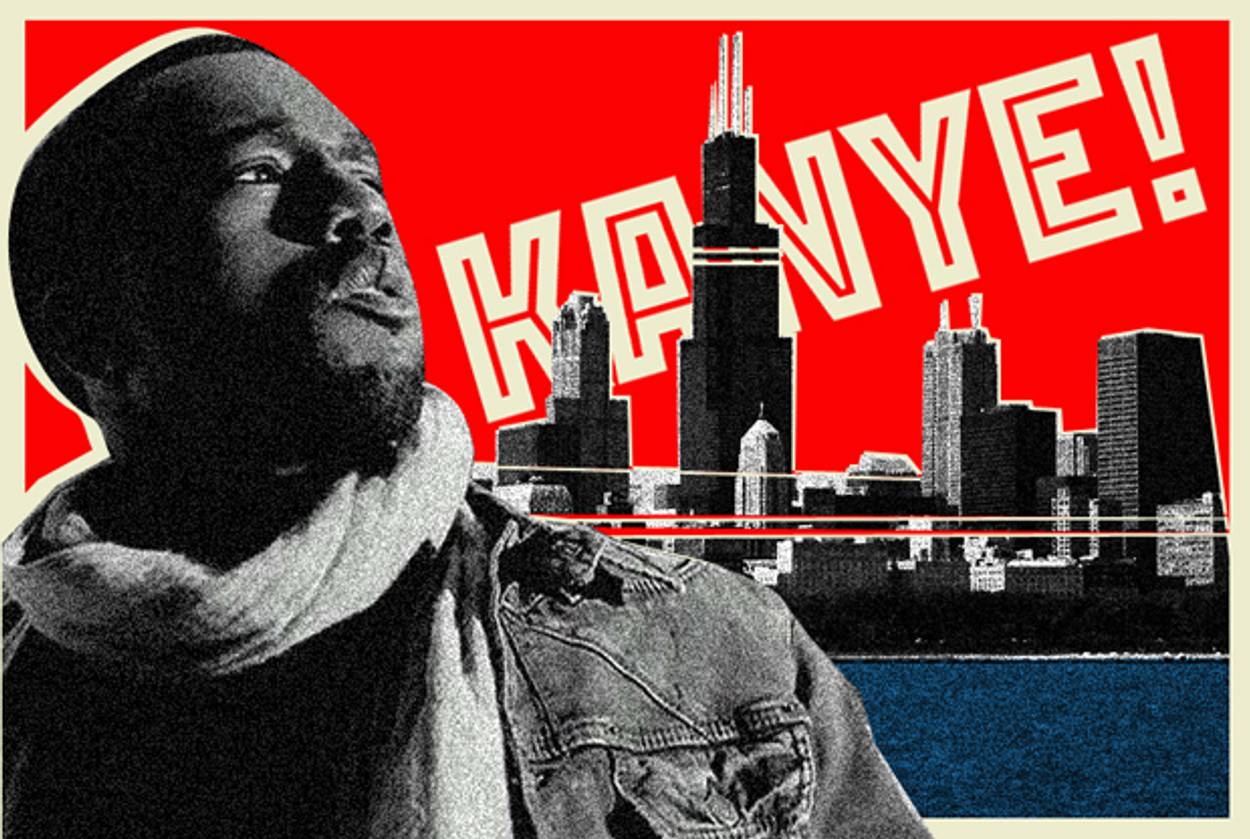

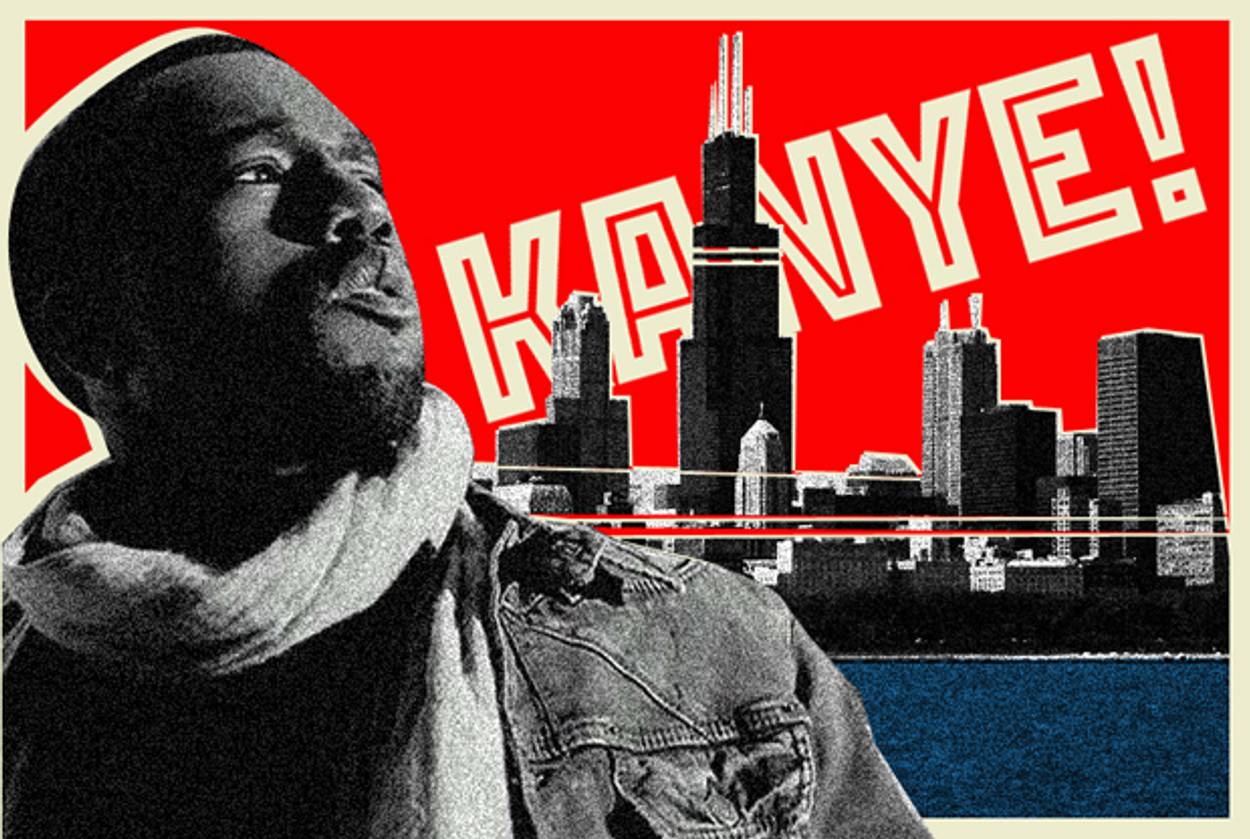

Graduation

A Jewish Ukrainian immigrant needed a voice to help reconcile her foreign past and her American future. She found it—in Kanye West.

In my family, we did not have taco Tuesdays or Scrabble nights. Instead, each Sunday morning, Baba Lala—my mother’s mother and the family matriarch—recreated the favored idyllic moments from our native Ukraine, via buttered potatoes with dill and smoked fish, sweet-cheese cakes and kefir. In the background, the blaring voice of Martochka on AM1330 Russian radio competed with my beloved MTV. Every so often, I would ask out loud the question that reverberated constantly in the quiet of my own mind: “Are we Ukrainian?” Always, the response was an exasperated “No.”

“No,” I repeated, often before stealing a confused glance in the mirror at my mail-order-bride-like looks.

In 1988, at 2 years old, I immigrated with my mother to Chicago, where we were reunited with the rest of her small family, who arrived the year before. Born the week of Chernobyl, I joined the hard-knock life that my family had been trying to escape for years: threats of Siberian prison and quiet KGB murders, a history of government-imposed mass-starvation in Europe’s breadbasket, losing everything from established careers to spiritual freedoms, and a censored nuclear meltdown. It’s not a past that many of the immigrants in my mother’s and grandparents’ generations shared with us kids, even when prompted. They wanted us to have a clean slate in the new world.

And I did—in part by getting used to change and in part by realizing, as I did early on, that there was one constant in my new life: Top 40 in Skokie was Top 40 in Highland Park. I quickly fell for hip-hop, with B.I.G. and Missy Elliott as early favorites. But maybe it was his timing, city, or drive that attracted me most to Kanye West as the voice of reason who eventually reconciled me with my immigrant past while readying me for my American future.

“Champion”: Did you realize that you are a champion in their eyes?

My mother’s gold chains and Eurolux couture matched the nonchalant gaze above her high cheekbones more than she knew. I remember being a 3-year-old FOB sitting in the fine leather upholstered chair at Bebe on her days off, spending hours watching her work her style. Distinguished from Eurotrash in the attitude of its bearer, “Eurolux” tastefully emulated European fashion while symbolizing the acceleration to a greater quality of life without being a mockery of itself—clothing that didn’t make the woman but reflected her. I lived in a 1990s Chanel perfume commercial.

I found this style, indeed the whole world of “SovJew” immigrants, to be detached and off-putting and distanced myself from it from a young age. Instead, as a teenager I committed most of my brain space to out-of-the-house endeavors, from art classes to jobs to boys. I barely flinched at Baba’s scorn when my Russian language skills abysmally sank into the categorization of party joke. I didn’t give a shit about the lost opportunities for conversation with heavy-tempered adults at home or bookish Russian girls who insisted on remaining foreigners at school.

During a group project in high school, I found myself in the company of a classmate from the Mayer Kaplan Jewish Community Center daycare. Another child-immigrant, she was probably the only other person in my world who could understand my collaged sentences of Russian, English, and Hebrew. While we were working on the project in her suburban townhouse, her mother asked me a question: “Do you know what ethnicity you are?”

“I’m American now,” I replied, glancing at the map on the wall.

“No,” she castigated in Russian. “You are an immigrant. You will always be an immigrant.”

I was furious at her. I could not equate this provincial identity with success—until I left the suburban confines five years later and was able to replace these figures with Kanye as my mentor.

As I entered college in 2004, Kanye’s debut, College Dropout, was released. Kanye, who also arrived in Chicago as a kid with his single mother, was an artist and good student in the suburbs. Kanye’s father was a former Black Panther and his mother an English professor and chair at universities, and his upbringing was under similar auspices geared toward rebellion and education as the way up. Like his politically conscious predecessors, he refreshed popular thought with newly relevant questioning of loudly preached common sense on wealth, education, and individual empowerment beyond class. What worked for me was the palimpsest-like layering of social consciousness and sex, fresh production and classic samples. That he was making bank proved that he was a trustworthy mentor, as good a guide to the American landscape as I’d find.

“Good Life”: Like we always do at this time, I go for mine, I got to shine

That girl’s mother was right: I was on the outside of everything. But I was also, I soon began to realize, extremely adaptable—a quality that, in college, made me the perfect student of anthropology. The science allowed me to critically think about groups I did not understand in their proper context, including my fellow Soviet Jews. As I became comfortable in the company of just about anyone, I schooled myself on my immigrant past and began to own it. The identity began showing up in my art and writing. I did as the MCs did, acknowledging the suffering from my past that nobody else wanted to talk about while empowering myself to progress beyond it. I even took Russian classes—my grandmother’s best argument of the language being a marketable skill finally appealed to me. Exploring further, I headed to Prague for a couple of semesters during which I steeped myself in the post-communist landscape among those who did not flee, seeing the varied ways that individuals sank or swam as their circumstances blew up in their faces. This was my past, I now knew. When Nas asked, “Whose world is this?” I began to answer, “It’s mine, it’s mine, it’s mine.”

I soon moved to the city proper, and Chicago became a drug that induced further clarity and art. An American boyfriend romanticized the Jewkrainian immigrants, even finding amusement at functions with my family in the Russian banquet halls that I abhorred. Sequestered in this urban diversity, I felt saner; I was able to both escape and come home. Again looking in the mirror, this time with hair remover on my upper lip, I felt a weird Amazonian pride in the European mark I bore for which Baba Lala’s genes were responsible. I was certain that feature was on the same chromosome as my work ethic, physical strength, tits and ass. It occurred to me that these not only helped a Jewkrainian woman thrive in her own domain, but they also proved alpha qualities in the hip-hop world. Doing my thing where Kanye was king, I could not help but relate to his philosophies. While The Pharcyde told me “Can’t keep runnin’ away,” Kanye gave me permission to define success in ways beyond what the older generation of immigrants prescribed. Because I did not want to be anything close to a pharmacist, I had no examples for the success I was chasing as an artist. Kanye’s value of a trajectory beyond the limits of status was identical to the immigrant dream I grew up with, but now the message was relevant to my own success.

A few years later, Kanye’s confidence began to tarnish his image in the eyes of critics as well as followers. But it secretly turned me on. It meant that, like the immigrant mindset, he was equipped to survive and thrive in whatever circumstances the unknown future might throw at him. The 2009 Taylor Swift debacle turned many of his fans against him. While he was uncouth with the timing he chose for bashing the cranked-out Idol star’s poverty in talent, it was truly consistent with his confident make-up: It was undeniable that he was accountable for his opinion and that he exercised his voice in a forum in which he knew he would be heard. Kanye was loyal to justice and truth above goodness, something that grates on the nerves of a largely moralistic public. He did it for the glory. Most important, he found his own success while acknowledging the greats to whom he owed his footing. It really is the true dream to achieve what Kanye did in his latest, Watch the Throne, in collaboration with Jay-Z, where we as the freshest generation might attain that enigmatic approval for achievements that allow both generations of legends to thrive.

This summer, while preparing for an exhibit at New York’s KGB Bar commemorating the anniversary of Chernobyl as well as promoting transparency and active democracy, I gave my sister in Los Angeles a phone call. “Maybe I’m listening to too much Kanye,” I told her. The playlist behind the series of propaganda paintings was very hip-hop heavy, especially looping Graduation, an album that was speaking directly to the Soviet experience I was portraying. “All of a sudden,” I said into the phone, “I’m daydreaming about getting a flashy grill.”

“That’s nothing new, Rita,” my sister said, before reminding me of something I had completely forgotten. When I was 11, I took a trip to Israel to visit my father’s family for the first time, where I told my sister that what I wanted more than anything was to replace all my teeth with gold one day.

“Just like the babushkas,” I said.

For more lyrics and analysis, visit Margarita Korol’s website.

Margarita Korol is a pop artist and designer in New York City.

Margarita Korol is a pop artist and designer in New York City.