A Graphic Account of a Soviet Daughter

Julia Alekseyeva’s moving tale of her great-grandmother, a Russian refugee, and the perils and promises of idealism

Just after Trump signed the first “Muslim ban,” a document began circulating online. I paused at its title: “Soviet Jewish Refugee Solidarity Sign-on Letter.” I grew up in New York City, where I went to public school; since I was a teenager many of my closest friends have been Jewish émigrés from the Soviet Union. For 20 years, I’ve heard stories about selling off libraries accumulated over generations, saying goodbye to friends and relatives for what might well be the final time, spending months or years of purgatory waiting, in Western Europe or Israel, for an American visa, without a passport, without a nationality. I’ve heard about anti-Semitic slogans written on mailboxes or cried out in Soviet streets, or at jobs, or about university places deserved but denied. I struggled to imagine myself in these painful stories, out of my own comfortable, safe childhood on New York City’s Upper West Side, a place where even gentile children learn Jewish prayers by attending countless bar and bat mitzvahs. And yet I’d never quite thought of my Jewish friends from the Soviet Union as refugees. I’d met them after the hardest part was over, when their parents—many of them scientists and intellectuals stripped of their credentials by emigration—had already managed to fight their way back into the professional classes, and after their children, my friends, had already lost their accents. I had always associated the word refugee with people fleeing from bombings, famine, or outright genocide, people from impoverished, war-torn hells like contemporary Syria, Yemen, Sudan, Libya, and Iraq, people trying to outrun death. But I was wrong, of course.

Many of my friends and some of their family members soon signed the letter, providing the years in which they’d immigrated: 1981, 1987, 1989, 1991. I kept checking the list, seeing an ever-growing number of familiar names. As protests against the refugee ban mounted, several of my Soviet Jewish refugee friends, as I had now learned to think of them, posted on Facebook about the great hope that their families had felt as they arrived in America, as well as the shame that they had experienced as refugees in hand-me-down clothes, with bad English and heavy accents, sometimes in communities where they were one of only a handful of Jewish families. My friend Anna Kats, a Soviet Jewish refugee from Tbilisi, wrote an especially moving note after the spontaneous protest at JFK:

When I was a child, adults would talk about coming to America with refugee status like it made the traumatizing experience of leaving your home, your friends and possessions, your career, your favorite streets, your hangouts and museums, your ancestors’ graves and your language worthwhile. If you came as a refugee, you had some bureaucratic and financial support while your parents tried to acclimate, begin life anew in middle age, and rebuild the careers they’d had in the Soviet Union, or wherever else; you had the sense that someone, somewhere empathized with your family enough to rubber-stamp their application to come here (but not at school where you were taunted for being an immigrant by the white ‘American’ kids); you had the sense that if you abandoned your mother tongue and worked hard to assimilate, maybe you wouldn’t have to be ashamed about being a refugee forever.

But now it gives me pride to see so many of my friends and acquaintances embrace refugees, and I can only hope that these immigrants will find a more hospitable country when they finally arrive (because, of course, they must and will come). America is a frustrating, deeply flawed place, but it gave me a life and I am immensely heartened by the fight to ensure that other refugees can live, too.

Sadly, the ban opened a rift between generations; the swell of compassion for refugees was concentrated among the young. More than a few older Soviet Jewish refugees support the new ban, convinced that they were the good refugees, the ones who deserved to be let in, while Syrians, Iraqis, or Yemenis are murderers and thieves and layabouts who must be kept out at any cost. Younger people swapped stories and then asked, “But what do your parents think?”

One of letter’s Soviet Jewish signatories was Julia Alekseyeva (1992). Though Alekseyeva began writing her new graphic memoir, Soviet Daughter: A Graphic Revolution, before Trump had even appeared on the political horizon, the memoir feels particularly apposite today, as American anti-Semitism rises under a president at ease with conspiracy theorists, and as the United States faces a level of political turbulence that many of us associate only with distant countries—the kind that produces refugees.

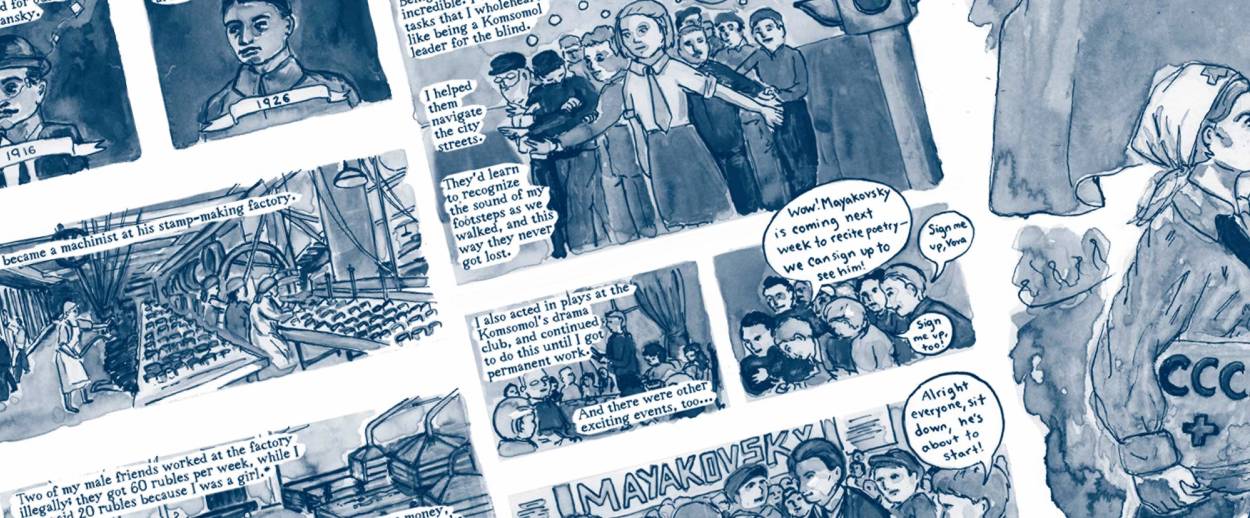

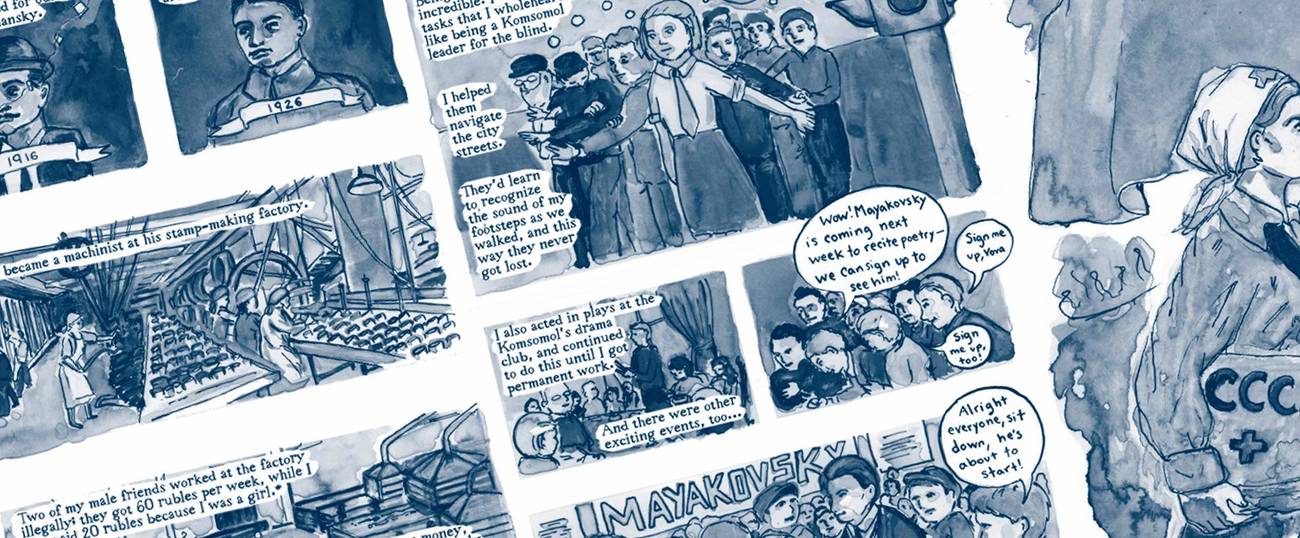

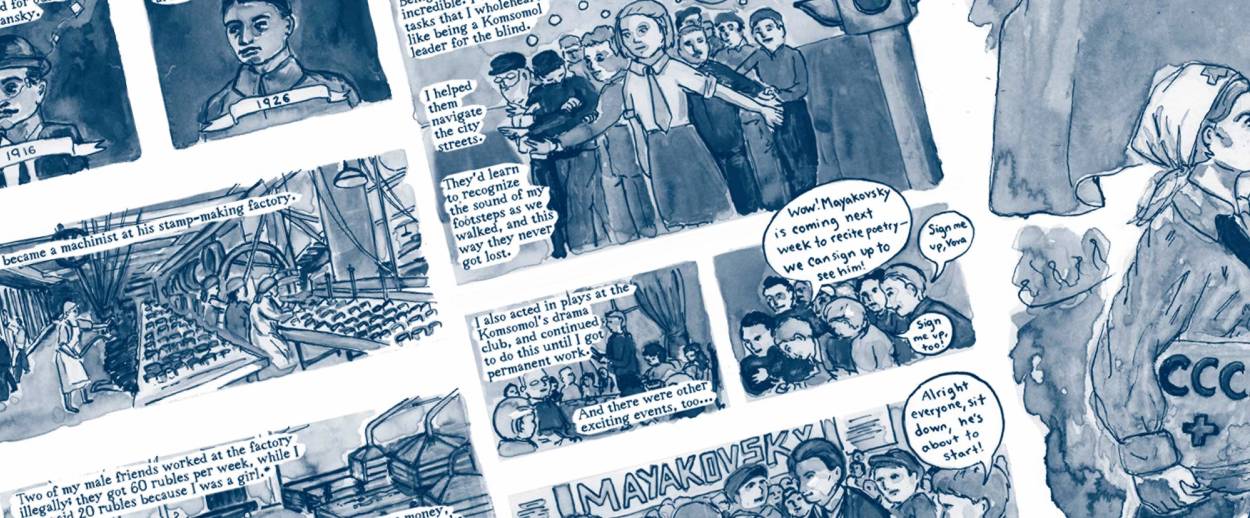

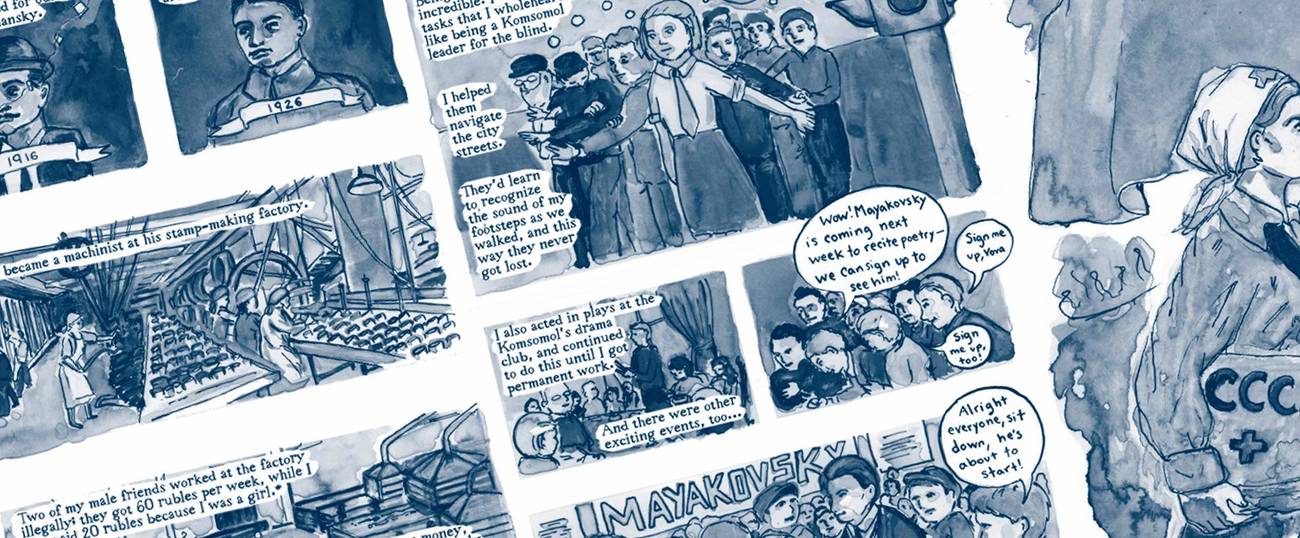

Soviet Daughter is a double life story: of Alekseyeva, who emigrated from Kiev to Chicago as a 4-year-old, and of her great-grandmother Lola, who was born in 1910 and lived to see her 100th birthday, surrounded by her family and friends, in Chicago. Affinities often skip a generation or two, in terms of family relationships as well as political sensibilities. The emotional core of Soviet Daughter is Alekseyeva’s profound bond with Lola. As Alekseyeva puts it, “I just never got along with anyone else in my family. An unnavigable rift formed between us when we immigrated to the U.S. in 1992; we spoke the same language, but no longer understood one another. Lola, however, was a different story. I felt she understood me perfectly.” When her family arrived in Chicago, Alekseyeva’s single mother and grandparents spent their days working or studying. Alekseyeva did not yet speak English, and the neighborhood children taunted her with their own fluency, even when they were Russian themselves. Alekseyeva’s mother hoped to hide her family’s Jewishness even after they resettled, believing that it would evoke the same discrimination it had in the Soviet Union. She forbade Alekseyeva to tell anyone she was Jewish, or to wear long skirts that might make her look like the neighborhood’s Orthodox girls. She wasn’t even allowed to attend her best friend’s bat mitzvah, for fear that people would “find out.” But of course everyone knew already, and at school, she was taunted with names like “Anne Frank,” or told that her good grades were the natural result of her Jewish blood. Lola was the only family member who seemed able to accept her and to accept the family’s Jewishness as something natural, not a source of shame.

But Soviet Daughter is primarily about Lola, written in her own words. In old age Lola wrote her memoir, instructing her family not to read it until after she’d died. When Alekseyeva discovered it, still reeling from the pain of losing her beloved great-grandmother, she was so astonished that she decided to make it into a book.

Born to a Kiev jeweler and his wife, Lola grew up in Podil, Kiev’s Jewish district, spending her early years in a house on stilts high enough to preserve the family from the Dnieper River’s periodic floods. Lola was a small child at the time of the Beilis Affair, in which a Jewish man, Mendel Beilis, was framed for the murder of a Ukrainian boy, supposedly in order to use his blood in a holiday ritual. This was only one of many examples of spectacular, incendiary anti-Semitism that Lola witnessed. Her family lived on edge, always alert to signs of the beginning of the next pogrom.

Against the odds, Lola’s family survived the revolution and ensuing civil war, pogroms, epidemics, and famine. Poverty was a constant. At 10, Lola became responsible for caring for her six younger siblings; her mother was an invalid. She left school after fourth grade because she didn’t have time to balance school with her housework, and later with her work as a seamstress. The family was so poor that they had only one pair of winter boots for the nine of them; the first person to snatch them was the one who could go outside.

Like many impoverished Jews, Lola embraced the Soviet project, hoping that it would put an end to poverty and anti-Semitism alike. As a young factory worker, she joined the local Trade Union and became an avid Komsomol member. She was lucky enough to survive Stalin’s purges, offered a job as a typist for the secret police. (She says that because of her low rank she knew only about minor crimes, although she was aware, of course, of the wave of arrests.) Her job meant that she was evacuated to Kazakhstan when the Nazis approached Kiev, which saved her life and the lives of her children; most of her family died in Nazi massacres or while fighting in the war. Even as she worked day and night for the war effort, she could barely clothe or feed herself and her children, and she was evicted with no notice when her landlady discovered she was Jewish.

Like many true believers who had devoted their youth to the struggle for communism, Lola was shocked when Khrushchev denounced Stalin’s crimes in the 1950s. “My faith collapsed,” she says. “There was nothing sacred left. I felt an unbearable emptiness.” But she endured the loss of her utopian dream, just as she had endured the loss of her beloved husband and most of her family, and she saw her children grow up, marry, and have their own children. Her family had trouble persuading her to emigrate; she still believed that it was every citizen’s duty to work for the improvement of the Soviet Union. But the Chernobyl disaster (which would later cause Alekseyeva to develop thyroid cancer) persuaded her at last, and she left the USSR along with three generations of her family.

Toward the end of Soviet Daughter, Alekseyeva draws a parallel between her own idealism, that of the Occupy generation, and Lola’s. After a century, we’re able to see the Russian Revolution and the early Soviet project with clearer eyes. The results—Stalin’s purges, manmade famines, the Gulag, and more—were monstrous. But as Soviet Daughter shows, the czarist order had been unbearable for a great proportion of the population; this was, in part, what made revolution possible. In the United States, decades of unrelenting condemnation of the Soviet Union nearly erased the memory of idealists who devoted their abundant courage, energy, and ingenuity to an effort to create a better world. The high hopes of people like Lola are worth remembering. In the years since Lola has died, Alekseyeva writes, alongside illustrations of Occupy protests and union organizing meetings, she’s become more optimistic: “Enough to retain hope for something better. Enough to want to fight for something against all odds. … After all, governments might change, the historical period might shift, generations might differ. But nothing, not all the guns and pepper spray and police batons in the world, not even time, can kill a true idea.” Refugees of the world, unite.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Sophie Pinkham is the author of Black Square: Adventures in Post-Soviet Ukraine.

Sophie Pinkham is the author ofBlack Square: Adventures in Post-Soviet Ukraine.