The Proust of Disillusion

Remembering the Hungarian writer and dissident György Konrád, who died last month at age 86

“Once the child who needs no stories comes into this world, we must all start to worry.” —György Konrád, A Guest in My Own Country

It is as children we first discover that literature enchants us because it opens doors and shows us worlds we didn’t even know existed. We never outgrow that enchantment with stories, and in 1987, at the age of 37, I stood captivated in a bookstore in Atlanta, when I picked up a copy of The Case Worker, by György Konrád and started reading. I felt a door opening before me.

A year after that, I did indeed step through a door: the door I closed to my house in Atlanta after I sold everything I owned in America (except for my books, of course) and flew to Budapest. That was followed by the door I knocked on in Buda and Konrád himself welcomed me into his home. Then there was the gate, not really a door, of the Farkasreti cemetery that I went through last month, Sept. 25, 2019, when I attended Konrád’s funeral, who died at age 86.

Before that day in 1987, I had never read a Hungarian novelist—or any writer from Communist Europe, but thanks to Philip Roth and the Penguin series of Writers from the Other Europe, I was discovering fiction so different from anything else on the market that I started hoovering them up. After all, I was reading mostly American Jewish novelists and Southern fiction. None of those writers were being arrested, thrown out of their countries, or were smuggling manuscripts out with foreigners. Words just seemed to have more weight over there. Roth himself summarized it in an interview in the Paris Review when he said he lived in a society where “everything goes and nothing matters, while for the Czech writers I met in Prague, nothing goes and everything matters.”

For me, Konrád’s The Case Worker was all about what matters. Here an unnamed social worker in what we presume is Budapest oversees cases of abandoned children in a social welfare office, and in 180 pages, the social worker takes us into the filthy flats of suicides, ill-lit bars where the hopeless sit and drink, and his own dingy office where “I question, explain, prove, disprove, comfort, threaten, grant, deny, demand, approve, legalize, rescind. In the name of the legal principles and provisions I defend law and order for want of anything better to do.” Not exactly the socialist paradise Communism was trying to show to the world.

When the book was released in Hungary in 1969 it sold its entire print run of 6,000 copies in a day, but the publisher was not allowed to reprint it. Nor would any of Konrád’s novels see print in Hungary until the late 1980s, other than a badly mangled version of The City Builder. He was interrogated by the police, jailed on occasion, but he refused to emigrate, all while his international reputation grew exponentially, especially in West Germany, the Netherlands, and Austria.

When I moved to Budapest in March 1988, one of my first stops was to see Csaba Csikes, the U.S. Embassy public affairs officer well known for supporting political dissidents. When I told Csaba how much I loved Konrád’s work, he scribbled down his phone number and address. “Go see him. He likes company. Just so long as it’s not the police.”

Turns out I was living nearby. (Not “can I borrow a cup of sugar” close, but close enough.) Instead of phoning—I couldn’t bear to imagine what a fanboy of a Hungarian dissident novelist sounded like on the phone—I decided to knock on his door.

Which I did, and while standing in the doorway, Konrád listened as I told him I was living in Budapest and loved his work, and he replied, in a voice so deep that it barely registered, “Ohhhhh (he usually got three syllables out of that word) do come in,” and as he shuffled (he always shuffled) into his not surprisingly booklined living room, said, “what do you mean, you live here?”

I told him that for the past three years I had been photographing and writing about Jews still living in Communist countries and had spent most of my time in Romania but felt if I were going to do things right I’d have to live in the region, and Budapest made the most sense because it had more Jews than the rest of the region combined.

György, or as his American publisher called him, George, and as his friends called him, Gyuri, took me into the kitchen to meet his wife, Judit Lakner, who was feeding their two small children. We all sat at the table, slices of bread and cheese went round, and after a few stories and comments about politics, Judit said, “Come back any time.”

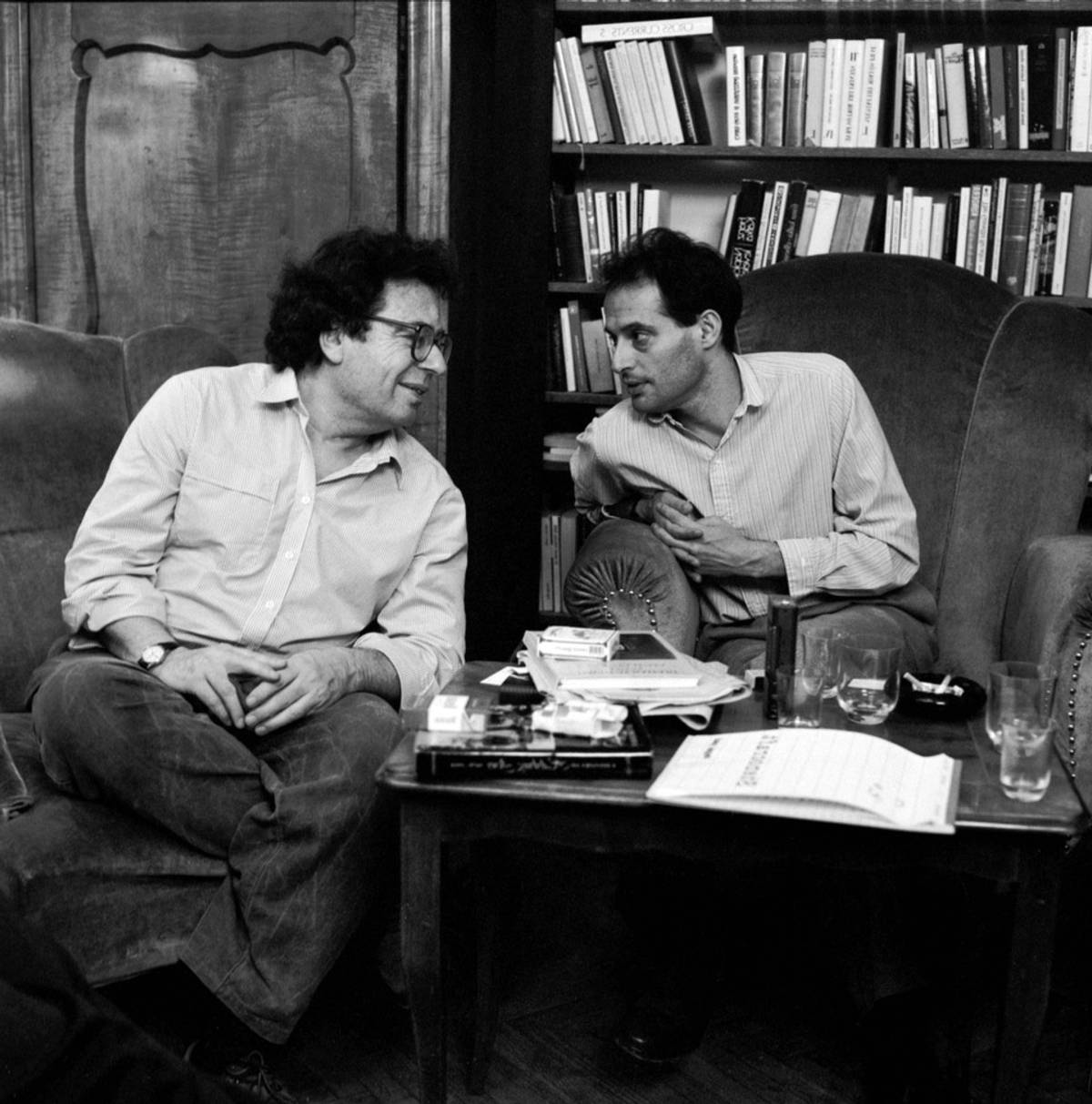

I did return, sometimes with the Konráds’ friends, Miklos Haraszti and his wife Antonia Szenthe.

Miki was, like Gyuri, one of Hungary’s best known dissidents and had written Worker in a Worker’s State, about the grim conditions on the assembly line. One German intellectual called it the Winnie the Pooh for young leftists. It also landed Haraszti in jail and on trial. As I watched the two of them speak in Konrád’s home, it was clear Konrád was something like an older brother. I took the picture of the two of them here in late 1988. And it would be Haraszti who gave one of the emotional, tear-streaked eulogies at Konrád’s funeral 31 years later.

As the Communist Party tore itself apart in 1989 with divisions between reformers and hardliners, I asked Konrád if it really would split. “Ohhhhhhh,” he said, “the party is like a very bad marriage. Both sides hate each other but neither side wants to give up the house.”

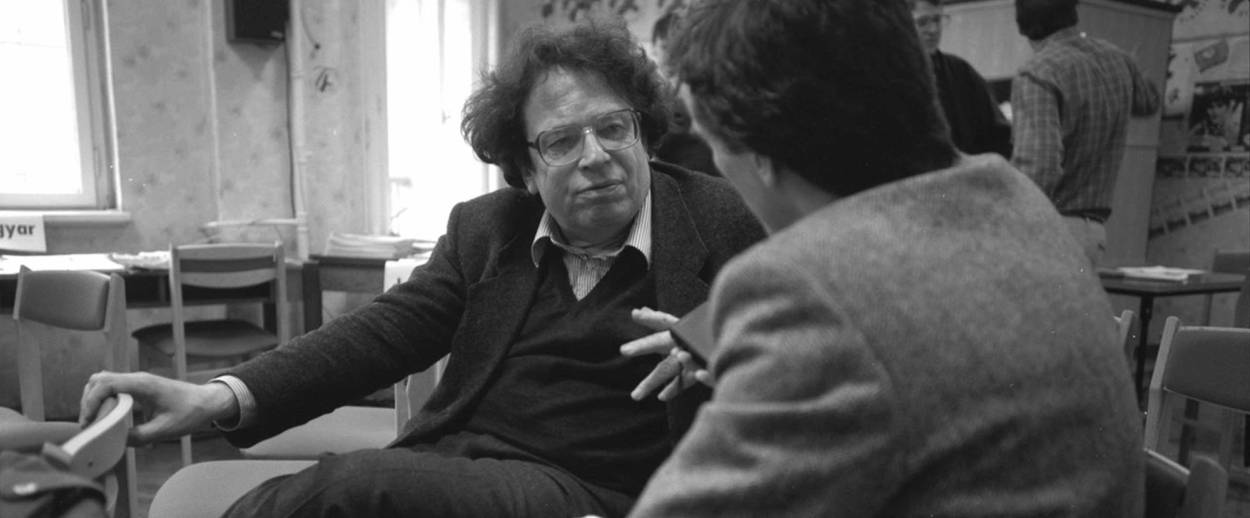

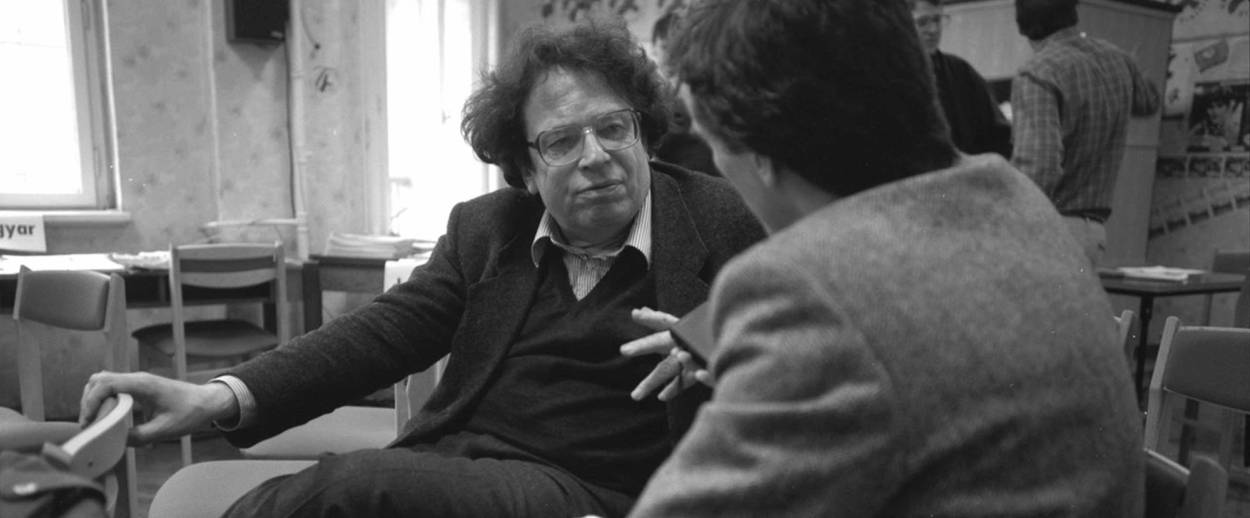

But the party did split and Konrád and Haraszti became founding members of the Liberal Party. I took one of the pictures here of Haraszti speaking with steel workers in the industrial town of Salgotarian; I even drove him there and back just so I could observe how a country hatches a multiparty democracy, meeting by meeting, one conversation after another.

After democracy came to Hungary, more than a few people thought Konrád should become the country’s president, but instead, Konrád accepted the presidency of the world PEN Club between 1990 and 1993; three years later he and Judit and their children (there was now a daughter) moved to Berlin, where Gyuri served as the head of the prestigious Academy of Art—the first foreigner to hold the post.

All the while, his earlier novels were published at home and he appeared on television and on radio regularly. He also produced enough nonfiction to fill volumes of collected essays in several languages, all while accolades and awards piled up at his door throughout the 1990s and early 2000s.

Once Hungarians could read Konrád’s banned novels, and as they found a broader audience abroad, readers discovered the unexpurgated version of his experimental second novel, The City Builder, which was followed in 1982 (in English) by The Loser, his longest novel yet at some 316 pages.

The setting came to Konrád when he was unemployable and had taken a job in a mental institute. In The Loser, his protagonist, locked in an asylum, looks backward to his Orthodox Jewish grandparents in rural Hungary, his spendthrift, womanizing father, his own escape from the Nazis and joining the Communist regime before going against it in the 1956 uprising. Kirkus Review called it “tremendously ugly” but “grimly memorable,” while Richard Sennett in The New York Times called Konrád “the Proust of disillusion.”

Konrád went on to write two well-received novels that were less experimental. A Feast in the Garden was his most autobiographical and was published in 1989; nine years later came Stone Dial. In both novels his characters take us to Budapest and Konrád’s hometown, which he calls Újfalu, and it seems whenever Konrád’s typewriter met the memory of his childhood, he was at his most endearing. But it was a childhood that turned to horror.

In both A Feast in the Garden and in his memoir, A Guest in My Own Country, (published in English in 2007), Konrád wrote that when the Germans occupied Hungary in April 1944, his wealthy parents were arrested and sent to a labor camp in Austria—but not as Jews—as war profiteers, as a local baker had informed on them. It saved their lives. Gyuri was 11 years old, and just in case, his parents told him where they buried their documents and some money, and his mother had—again, just in case—sewed gold coins into his and his sister’s clothes.

With his parents now gone, Gyuri took the documents and money to the local police chief, received the stamps in their documents they would need to travel, and left with his younger sister by train for Budapest.

The very next day, the Jews of his village, Beretttyóújfalu by name, were rounded up and sent to Auschwitz. Almost none returned, and the Konráds would be the only intact Jewish family in town.

In his memoir and in A Feast in the Garden, Konrád recounts the horrors of the Budapest ghetto in skin-crawling detail. He turned his head when his sister called his name, and just as he did so, a bullet tore through the pot of soup he was cooking. It would have gone through his head. On Klauzal Square he looked into a bakery to find only a giant stack of corpses inside, which he also saw regularly on the street.

In A Guest in My Own Country, his neighbor, a youngster by the name of Mário, was shot on the banks of the Danube, tied to his father, then thrown in.

But Mário managed to free himself and being only wounded in his arm, managed to free himself from his father’s corpse and crawl out of the freezing river. When an Arrow Cross soldier saw him coming toward him, Mário was far beyond caring.

“Shoot me into the Danube again if you want.”

“Jews are like cats,” said the old Arrow Cross man. “They keep coming back to life. Here he’s hardly out of the river and he gets cheeky. When it’s all over, they’ll have the nerve to blame it all on us.”

What György Konrád has given us through his fiction, his stand against the Communist state, his memoirs and in his essays, is that one lives by a moral code. No matter how small and powerless one is, no matter how hopeless the odds, one simply does what’s right and uses the tools one has at hand. It is what comes through in The Case Worker. As grim as things are portrayed—and Konrád piles up five pages in a single sentence at the end of the book listing the homeless, the unloved, the lonely, the abandoned, the discarded—Konrád’s social worker invites them all in: “at least we shall be together.”

I was reminded of how Konrád treated others one evening in the fall of 1989. The Hungarian Communist Party was in an advanced state of collapse, Poland already had its first non-Communist prime minister, and I was in the Konrád’s kitchen talking with Judit and the Harasztis. Gyuri was in the living room speaking with a journalism student from Kansas, who was stumbling through an interview and who sounded almost as naïve and fumbling as I did a year earlier. But Konrád—who knew what patience was—treated the lad with deference.

Suddenly there was a knock on the door and the bureau chief of a major American newspaper burst in and told Konrád he needed a quote and his opinion on something that was breaking in the news right then.

Konrád came to the door of the living room, smiled and said—slowly, and in that deep plate-rattling voice of his—“Oh … I am sorry … I am with another journalist,” and he waved his arm to reveal the scrawny kid on the sofa who had a tape recorder on knees pressed together and a notebook on his hands. “Please come back in an hour or two.”

The reporter said he couldn’t. He was on a deadline. It was important!

“I’m sorry,” Konrád said as he shrugged, and with that he gently closed the door and went back to the student, whose eyes were as wide as saucers.

At least we shall be together, I thought.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Edward Serotta is a journalist, photographer and filmmaker specializing in Jewish life in Central and Eastern Europe. He is the head of the Vienna-based institute Centropa.