An In-Person Report From a Virtual Film Festival

Binging documentaries while under quarantine in Haifa offers a much-needed window into a country that can feel unreal

It must have been the film festival’s logo—a little boy being lifted into the air by three film-reel-shaped balloons—that drew my attention. I had just emerged from the two-week in-country coronavirus quarantine that all travelers entering Israel must undergo. And now the country was on the verge of a second national shutdown (it would be “hermetically sealed,” my Israeli relatives promised)—which meant another three weeks inside my tiny Jerusalem apartment. So when the 36th International Haifa Film Festival’s lime green emblem popped up on my screen, promising a weeklong online escape into film, it felt irresistible. I registered right away.

For Jews in the diaspora, Israeli films offer a much-needed window into a country that otherwise can feel so far away as to be almost unreal. Jewish film festivals—before the era of streaming services, the only venue to provide such encounters—often cater to the specific interests and sensibilities of the diaspora. But what would an Israeli film festival geared toward Israeli audiences—the films at the Haifa festival had no English subtitles, and you could watch them only from Israel—look like, especially now?

As with some of the other adaptations that the coronavirus has forced upon us, a virtual film festival has its silver linings. I could not have seen as many films in person as I was able to pack into my online screening schedule. I had 24 hours to view each film from the time of its first screening and could watch each film several times within that period. The number of viewers per film was still limited, so you had to register quickly, offering a taste of the thrill of snagging seats to a live festival and the disappointment when “sold out” pops up on the purchase screen. I decided to focus on documentaries, so that I could use my confinement to explore some of the country and its people that I was unable to see or meet in person.

Bitter Honey recounts the story of a young man who decides to move with his young family to the Golan Heights and raise bees as a personal response to environmental crisis. In the Director’s Chair Sits a Woman features riveting monologues by 26 female film directors discussing their experiences in the Israeli film industry. Scattegories tracks the lives of three Nigerian kids who are longing to return to Israel, where they grew up as migrants, after their mother takes them back to Nigeria. Susita explores the colorful characters who stood behind Israel’s ambition to produce its own car—the Susita of the title—and turn the country into an automotive superpower.

In Secret tracks the stories of ultra-Orthodox Jews who have become disenchanted with the faith and observance yet remain in the community and are faced with the painful choice of continuing to live split lives or to leave.

The Church takes the viewer on a journey into the heart of Jerusalem’s Old City, to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. Director Anat Tel lifts the veil on the life, cohabitation arrangements, and power struggles inside Christianity’s Holy of Holies—the place where Jesus is believed to have been crucified, buried, and resurrected. She introduces us to the priests and monks of the Armenian, Roman Catholic, Greek, Coptic, Syriac, and Ethiopian Churches who live on the church’s premises and call it home. She also introduces us to members of the two Muslim families, the Joudehs and the Nousseibehs, which for 28 generations have kept the key to the church and open and lock its gates in a daily ceremony that may not have changed much since the 12th century, when Saladin, who wrested Jerusalem from the Crusaders, first entrusted them with the responsibility. Adeeb Joudeh recalls how moved he was when his father first let him, an 8-year-old, hold the ancient key: “It was as if the whole world was in my hands,” he tells Tel.

Within the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, invisible to the thousands of pilgrims who visit it daily, tensions run high. The space is divided among the denominations, and each carefully guards its territory. Father Samuel Aghoyan, superior of the church’s Armenian monastery, explains that one must be constantly vigilant. The Ethiopian Church offers a cautionary tale: Once the most powerful denomination inside the church, it lost its position in the 18th century and was expelled to the Deir Al-Sultan monastery on the roof top. Each denomination views its territory within the church as its spiritual country whose borders it must defend, explains Aghoyan, who has lived inside the church since 1956.

Overseeing order and security at this enormously complicated place is Johnny Kassabri, the Israeli police’s liaison to the church. An Arab Christian from Nazareth, Kassabri has had to become an expert on “the Status Quo”—the unwritten historical arrangement governing the place. It is the most complicated, “grayest area” in all of the Christian world, he tells Tel. If there is anything he has learned after his years of service in the Old City, he says, it’s “savlanut v’savlanut”—patience and more patience.

Some documentaries presented during the festival had little to nothing to do with Israel or anything specifically Jewish, addressing instead universal themes and questions. One of these was the delightful Fujinoyamai (whose original Hebrew title is Bilti niten l’refui, or Incurable Disease), by Sasha Tamarin. Tamarin takes us on his personal spiritual pilgrimage to Mount Fuji in Japan. The Japanese revere Mount Fuji as an emanation of the divine and a portal into mystical realms—and they are not alone in doing so. From across the Eurasian continent, Sasha had caught the bug as well.

What makes the film so enchanting is Sasha’s ebullient personality and genuine passion for the object of his spiritual affection. It’s what helps him ingratiate himself with the veteran photographer of Mount Fuji, Yukio Ohyama. Upon hearing Sasha’s impassioned plea, Ohyama agrees to accept him as an apprentice. (Let’s take him in, Yukio’s wife prods her bemused husband: Maybe the kid can help us out with household chores.) Ohyama introduces Sasha to the secret world of Mount Fuji lovers: amateur photographers who dedicate their lives to trying to capture, with their hearts and their cameras, the essence of the mountain. You must be patient, his new friends caution him: You approach Mt. Fuji little by little. Fall in love with her, and she will reveal herself to you.

Sasha throws himself joyfully into the pursuit. He contemplates the mountain from every possible angle. He studies the classification of clouds that wrap it. He runs naked through a yellow autumn field toward it and swims in a lake among its foothills. When the sensor in Sasha’s camera crashes from prolonged exposure to the sun, painting the sky, the water, and Mount Fuji itself pink, it’s as if we get a peek into the sensory overload of a spiritual seeker on the verge of meeting his beloved.

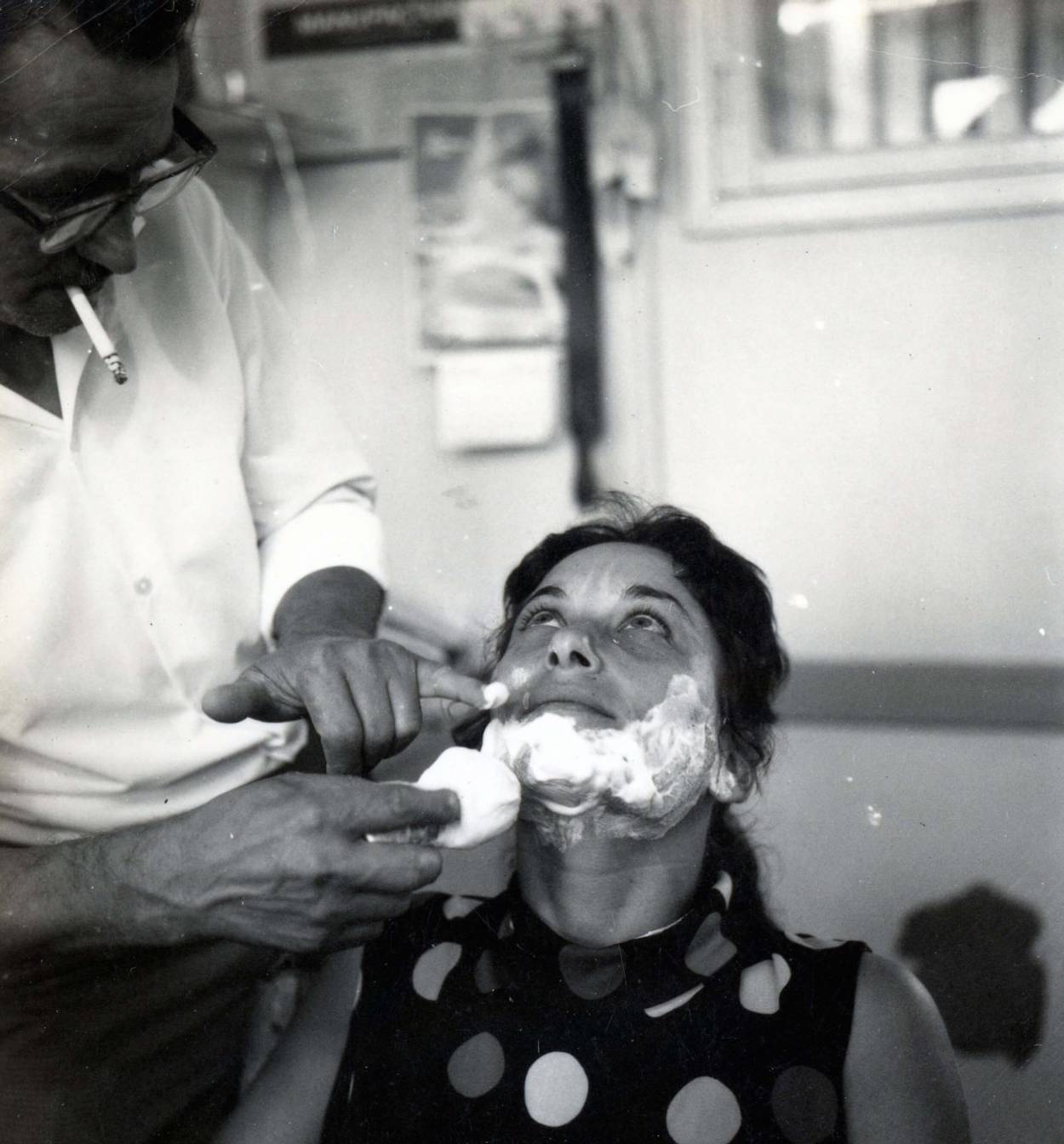

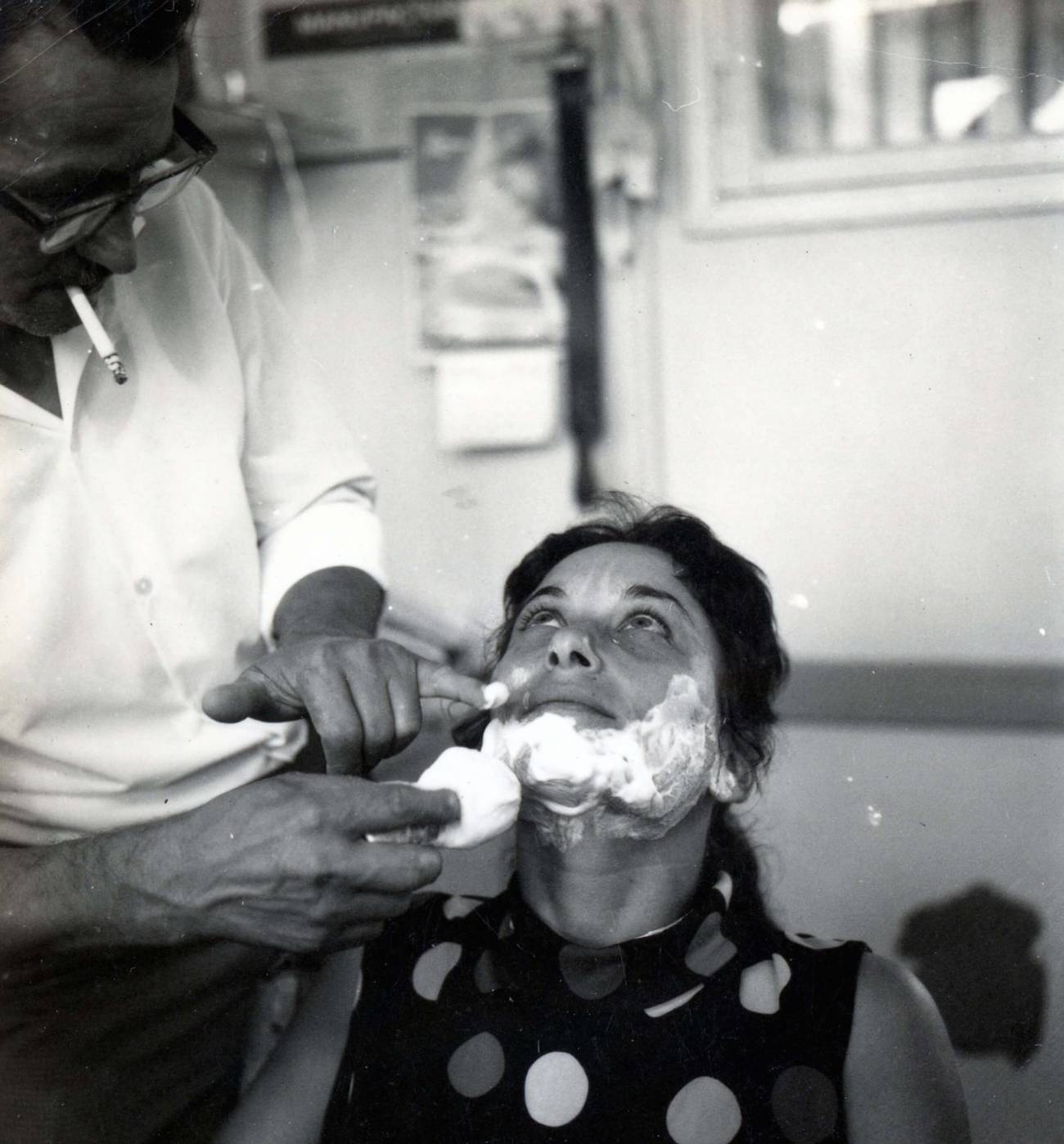

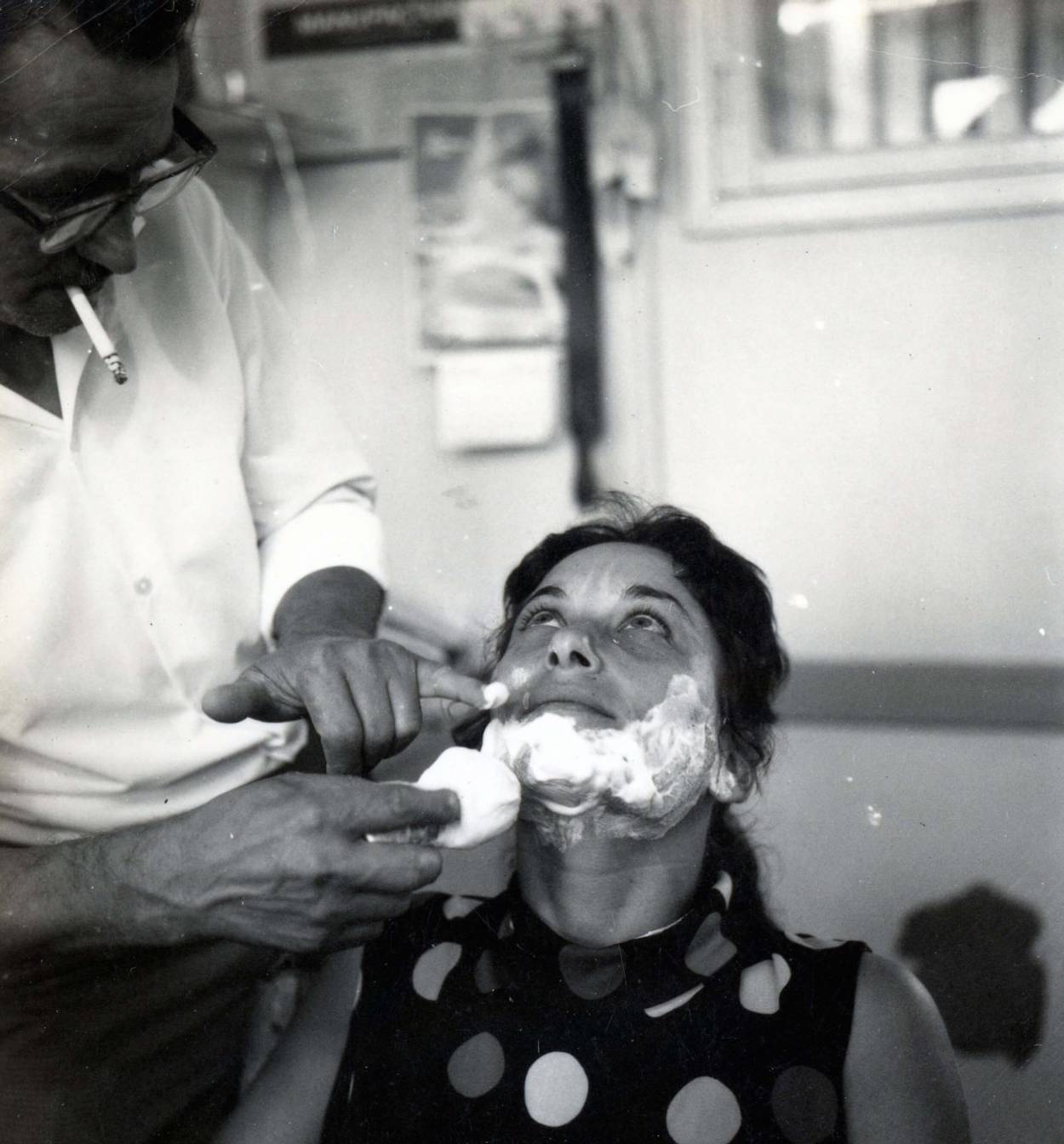

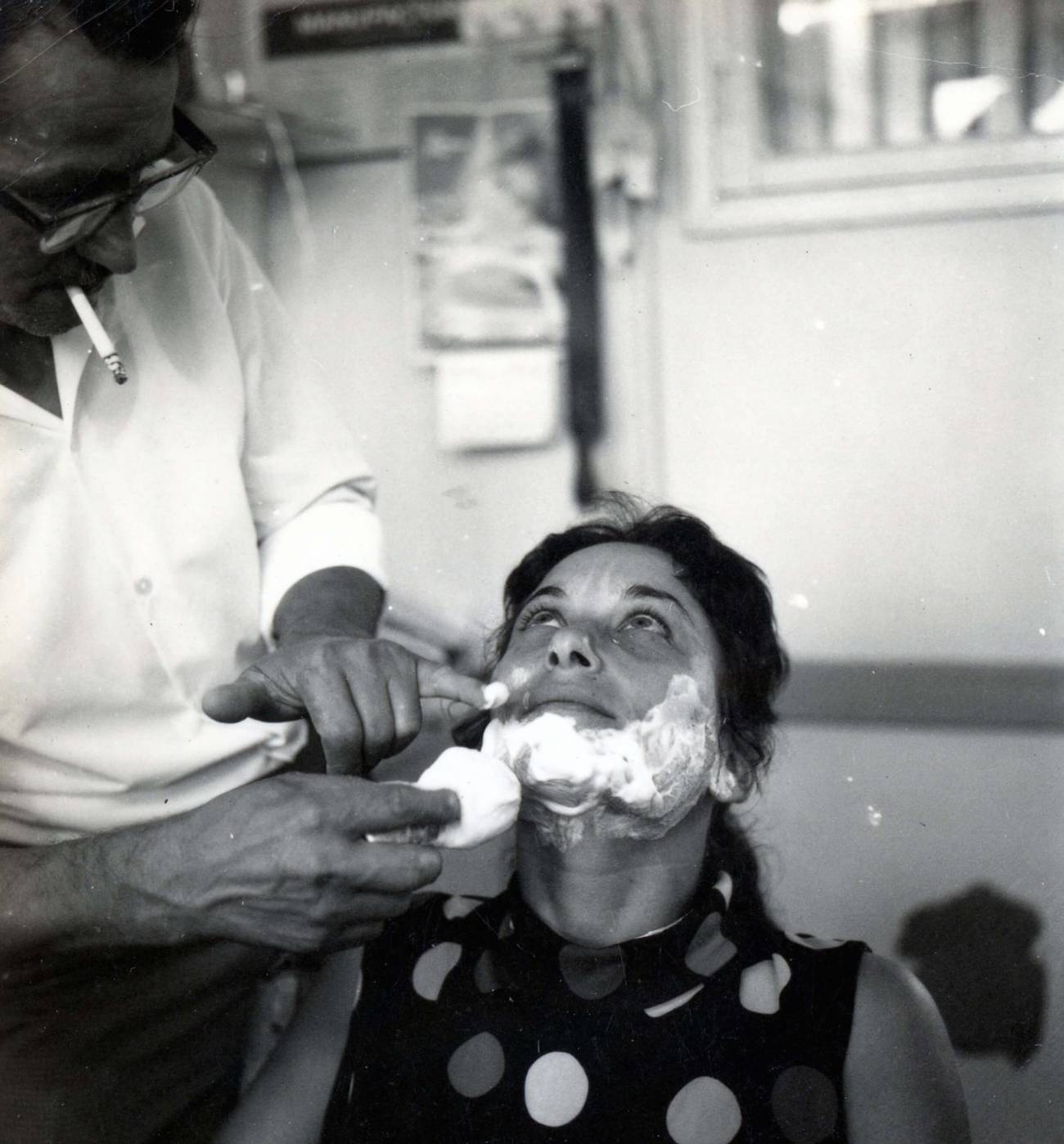

The autobiographical The Red Scarf by Peter Mostovoy offers a window into Soviet Absurdistan and its relationship with its artists. In the 1960s, Mostovoy was a member of the “Leningrad wave”—a group of young filmmakers who tried to modernize Soviet documentary filmmaking by ridding it of its socialist realism straightjacket. In Mostovoy’s 1966 short Take a Look at the Face, now a classic and part of film school curricula around the world, the camera contemplates the faces of visitors to the Hermitage Museum as they view Leonardo’s Madonna Litta. This straightforward depiction of response to art, without an overt ideological framing, was a radical departure from the Soviet documentary tradition.

Mostovoy was no dissident, nor did he have any inclination to use his art for political subversion: He simply wanted to make films about people who interested him, in ways that creatively engaged him. But like many others before and after him, he quickly discovered that in the Soviet Union, any creative act became political if it deviated from the narrow path of the officially permissible. His first encounter with the KGB happened when, as a college student, he displayed a homemade poster extolling the virtues of a sweater he was trying to sell at an open-air market. Minor private commerce of that sort was allowed, but the ideologically hostile capitalist act of advertisement got him expelled from the university.

As he tells his personal story, Mostovoy uses historical footage to touch on key events in Soviet history that shaped him. Reenactments take the viewer into the scenes of his encounters with the KGB and party officials. Some try to intimidate him, others, to co-opt. The director of the Lenin Museum in Moscow proposes that Mostovoy make a film in which the camera would display awed visages of the visitors meditating on the bullet holes in the coat Lenin wore when the Jewish socialist-revolutionary Fanya Kaplan shot him. (Only the most deserving patriotic citizens would be selected for the shoot, the head of the museum assures him.) Mostovoy declined the honor. When Mostovoy made a film about a group of young people visiting a former classmate in prison, he was accused of purveying Zionist propaganda for permitting a Jewish student be part of the film. Mostovoy made aliyah in 1992.

The festival’s prize for best documentary went to Leaving Paradise. In a journey that is both intimate and epic, director Ofer Freiman documents the story of a family living as a commune at a forest farm in Brazil. Cleo, the charismatic patriarch of the family, moved to the farm years ago with his wife and their 15 children to fulfill a lifelong dream. When we meet the family, the children are young adults. In this idyllic-looking setting, they work together and make joint decisions for the benefit of all.

But the idyll comes at a price. Cleo imposes his will on the family in ways both subtle and overt to ensure outcomes that suit his preferences. When the children discover the family’s Jewish roots and decide they want to make aliyah, Cleo’s resistance throws a wrench in the works. When one of the brothers decides that he wants to pursue aliyah on his own, an irreparable rift opens. When another son shares his dream of leaving the commune to travel throughout Latin America, other siblings pressure him to stay. The film’s core themes—the tension between the collective and the individual, the eternal lech lecha dilemma of following one’s destiny versus staying with the familiar—and stunning footage make for a captivating and thought-provoking experience.

By the time the festival was over, it was already clear to me that the shutdown was not as hermetically sealed as my Israeli family had promised. I took long walks through my neighborhood, where people congregated—at safe social distance, naturally—for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur prayers, and where sukkahs soon began to pop up in hidden courtyards, on balconies and on sidewalks. The warm October sun lit up the fuchsias, purples, and whites of blossoms pouring over the trellises and stone walls along the winding streets. Life was still all around us.

Izabella Tabarovsky is a Tablet contributor. Follow her on Twitter @IzaTabaro.