The Torah of Hakham José Faur

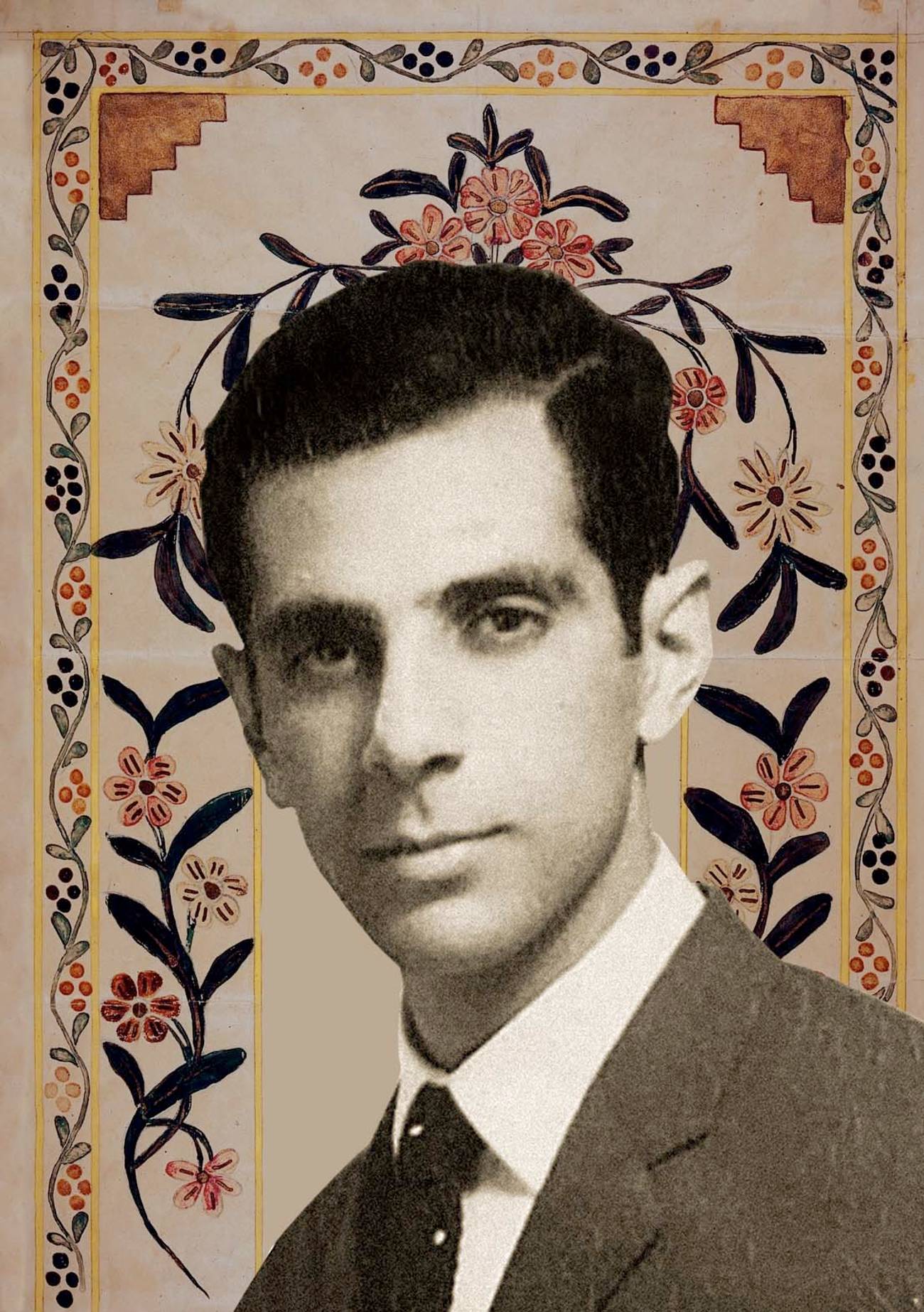

In memory of my ‘Tio José,’ a fiercely independent thinker who wrote passionately about Sephardic Judaism, rabbinic semiotics, and Jewish law—who became enmeshed in communal controversy for his ideas

In early June, the Sephardic world lost a giant in Torah—Hakham José Faur, of blessed memory, my great-uncle. Born in Buenos Aires, he was a scholar, rabbi and polyglot. His works were read by thousands of students who sought his academic and rabbinic counsel. Yet his loss was not noted by the broader Jewish community—perhaps because in both his intellectual projects and communal work he was a contrarian.

His rigorous intellectual tradition did not align with the current trend of identity politics, where to be Sephardic is mainly an identity. It did not fit popular American Ashkenazi diversity efforts, which too often focus on Sephardic cuisine or music over intellectual traditions. It did not align with the ideology of Shas, Israel’s powerful Sephardic Haredi party.

Hakham José Faur lived his life as a fiercely independent thinker who wrote passionately about Sephardic Judaism, rabbinic semiotics, and Jewish law—and in a time of growing herd mentality and rising awareness of the narratives that have too often dominated our communities, his intellectual legacy demands consideration.

My great-uncle’s lifework, his appreciation of what he called “Old Sepharad,” drew more from the 12th-century Sepharad of Maimonides than from the words and deeds of 20th-century rabbis of Sephardic descent. A lot had happened between the famed 12th-century rabbinic academy in Lucena, Cordoba (Andalusia), and the 20th-century famed Yeshiva of Porat Yosef in Jerusalem, Israel. Hakham Faur saw himself as representing a tradition that had been almost lost over the ages, and for which very few genuine proponents remained. He dedicated much of his life to understanding and explaining how Old Sepharad was lost and today’s “Sephardic” Orthodoxy represented a different approach.

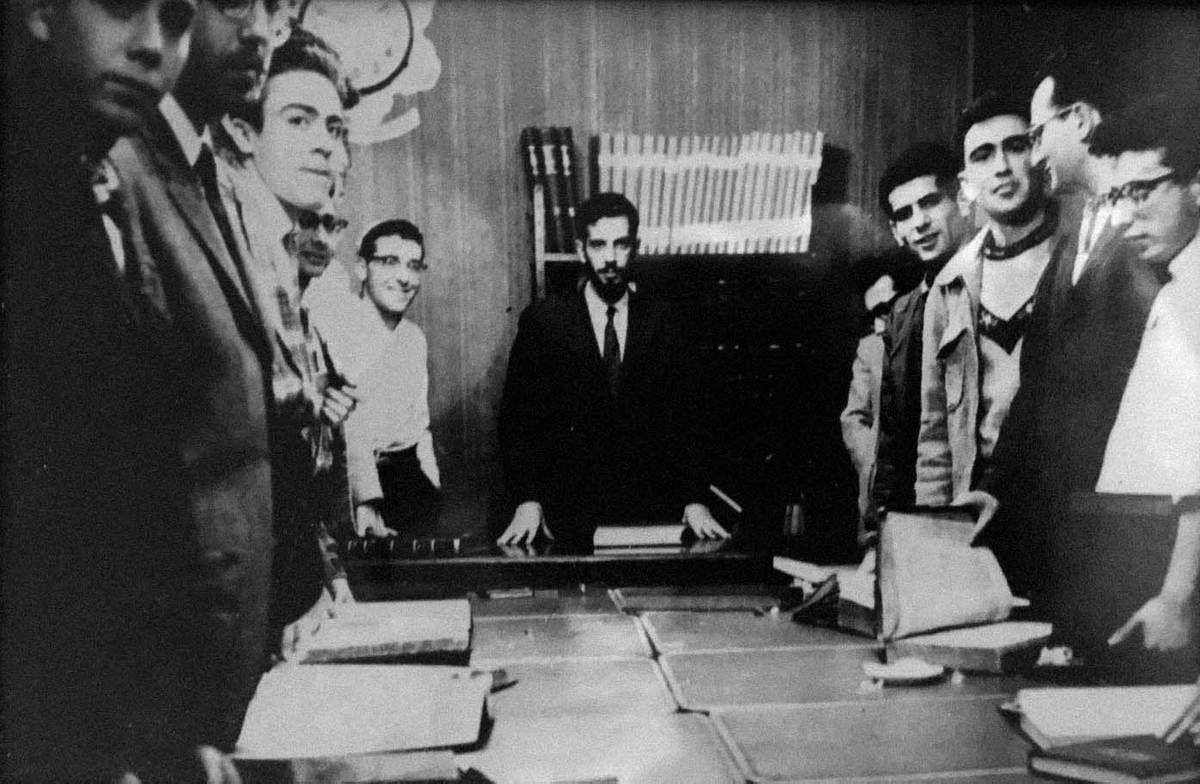

Hakham Faur spared no effort explaining why the tradition of Old Sepharad was superior to its alternatives. He revived the works of forgotten Sephardic sages and systematically described Old Sepharad’s intellectual tradition. He analyzed and criticized pagan and Christian thought; he chastised the Western academic approaches to Judaism since the Wissenchaft des Judentums—in his view—presented a frontal attack against the Jewish people’s right to be a living nation with living literary traditions. Within Judaism itself, he fought tenaciously against what he termed the “Anti-Maimonideans,” who, although Hakham Faur never said so explicitly, were intimated to have been the intellectual forefathers of Ashkenazi/Lithuanian Orthodoxy.

Once one recognizes that a certain intellectual battle is being waged in Hakham Faur’s writings, one finds an unambiguous combativeness in them—implicitly denouncing conceptual foes and at the same time shoring up the defenses on behalf of the philosophy of traditional rabbinic Judaism he so loyally championed. This orientation, a polemical project against so much of what is taken today to represent mainstream Jewish tradition, helps explain the brunt of the antagonism against Hakham Faur.

This intellectual antagonism was embodied, arguably, in a communal battle that took place in the Syrian Jewish community in Brooklyn beginning in the 1960s and reverberating till today.

In 1988, perhaps the apex of the controversy, a letter titled “The Torah view on Dr. Faur” went out criticizing Hakham José Faur and banning him from teaching Torah in this community. The letter included quotes attributed to 17 famous rabbis. Some, like R. Baruch Ben Haim, R. Shaul Kassin, R. Yosef Harari-Raful, and R. Elazar Menachem Man Shach, named Hakham Faur and banned him from teaching Torah in the community. Other quotes were teshubot of R. Ovadia Yosef and R. Moshe Feinstein, arguing that rabbis who had taught in Conservative seminaries should not be accepted as Torah teachers. And still others, like R. Shalom Messas, revoked their support—R. Messas had previously exonerated Hakham Faur from heresy charges—and bemoaned the nature of the controversy itself.

The accusations in the letter do not describe the precise ideological sins of Hakham Faur. The letter mentions that he taught at a Conservative seminary, a charge that “his books emit an odor of Heresy,” arguments that he was controversial, and an assertion that he was “a threat to the purity of faith and religion in the congregation.” Banned by community rabbis, including Haredi rabbis who were slowly gaining traction and influence in the Syrian community, like R. Yosef Harari-Raful, who today serves in the Moetzet Gedole Hatorah, Hakham Faur left Brooklyn.

It is difficult to parse out a singular reason why Hakham Faur departed from the Syrian community. “His books emit an odor of heresy” is hardly a falsifiable claim. Here, again, the narratives differ. Some think Hakham Faur was too brilliant, too much of a threat to the rabbis in the community. Others allege that Hakham Faur was proud, too aware of his own intellectual genius, and that it was his dismissal and critique of other rabbis which gained him very few friends. Some point out specific opinions or Halachic psakim he held which were controversial and different from those accepted within the communal mainstreams. Others see him as one of the first victims of the religious turf war that until today continues to grasp the Jewish Syrian community in New York—between the “black hats” (internal communal language for those more aligned with Haredi Judaism) and the “white hats” (those ideologically opposed to the black hats).

Whatever its sources, this communal excommunication shaped the rest of Hakham Faur’s life. After a stint at the Spertus Institute, Hakham Faur, a lifelong Zionist, moved to Israel and served as a professor of Talmud at Bar Ilan University and then a professor of law at Netanya Law School. In Israel he dedicated himself to teaching and writing and occasionally taught in Sephardic communities; he was invited as a guest speaker by rabbis such as R. David Sheloush, the then chief rabbi of Netanya, and R. Ezra Bar-Shalom, who then resided in Ramat Aviv.

From Israel, Hakham Faur continued leading a network of students and supporters who considered him their “Hakham.” He spent summers in Deal, New Jersey, the summer getaway for many Syrian Jews, where he gave regular classes. As his great-niece, I attended some of these intimate gatherings and was immediately struck by how different—how original—his teaching was compared with all the other shiurim of Torah that I was attending. Who else would use ancient Semitic grammar in a class to teach Miqra, the biblical text, sprinkled with casual references to the works of philosopher and son of conversos Francisco Sanchez, Sigmund Freud, and scholar of religion Mircea Eliade?

Despite having had the privilege to learn from him and read his works, I was not my great-uncle’s close student. This distinction remains the privilege of a select group of rabbis and scholars, students who formed a transnational bet midrash of sorts around Hakham Faur. But despite what some might assume, I was never excluded from this circle for being a woman. My great-uncle, whom my family affectionately knew as Tio José, was a staunch traditionalist and social conservative. But he always encouraged my intellectual pursuits. He invited me to his classes, asked about my doctoral research, and even mailed me articles he had written. His Torah was mine for the taking. And yet, something about his approach required a knowledge that I lacked.

I hadn’t grown up learning the te’amim (cantillation) to read the books of the Jewish Scripture, did not have a thorough understanding of Hebrew dikduk (grammar) and was not educated in rabbinic jurisprudence. When I began considering my own intellectual path as a young woman I was deeply cognizant—even embarrassed—of the educational gap between me and my brothers and knew it could not be remedied by translation. Hakham Faur approached text not as a conduit for concepts—which would be easy to translate—but as significant in itself.

With time, by learning from Hakham Faur’s students and reading his works, I recognized that my own experiences shed light on his intellectual project and the opposition he received. I developed admiration and appreciation for his monumental project, the attempt to revive Old Sepharad.

In honor of his memory, I wanted to offer a portrait of Hakham Faur’s biography, an explanation of his approach to Sephardic Judaism, a synthesis of one of his main ideas, that of “Alphabetic Judaism,” and a reflection on the implications of his philosophy. In doing so, I draw from my family’s history, the teachings of my great-uncle’s students, conversations with friends in the New York Syrian Jewish community and my own readings of Hakham Faur’s works.

My Tio José, Hakham Faur, was not only a virtuoso Hakham; he was a unique remnant of a Sephardic tradition that has been nearly forgotten. Those of us who care about this majestic and confident Sephardic heritage must keep his memory and his Torah alive.

José Faur Halevy was born in September 1934 in Buenos Aires, Argentina, to a family of Syrian Jewish immigrants, Abraham and Sebchia Faur, my great-grandparents, who immigrated from Damascus as economic migrants in 1929.

Already as a young boy, José Faur was an anomaly: In the backdrop of a highly secularized Buenos Aires in which Syrian Jewish immigrants struggled to make ends meet, he wanted to learn Torah. Young José Faur learned from his grandfather, R. Yosef Faur, and from Syrian Jewish emigres, Damascene Hakhamim R. Eliahu Freue and R. Eliyahu Suli, and Aleppian Hakhamim R. Jamil Harari and R. Aaron Cohen. They immersed him in a tradition that was learned and argued over in Arabic, Spanish, Hebrew, and Aramaic. In an autobiographical essay, Hakham Faur describes his early education as follows:

Following Sepharadic educational training, the teaching was methodical and comprehensive. Subjects were taught systematically, in a gradual fashion from the general and basic to the specialized and esoteric. This [sic], before one began to study the Talmud it was expected of him to have a solid knowledge of the Scripture, Mishnayot, the famous rabbinic anthology En Yaqcob, Shulhan Arukh and other basic Jewish texts. The scope of the curriculum was wide and universal, from the basics of Hebrew grammar to the niceties of rabbinic rhetoric ... Accordingly there was a serious effort to study some of the basic ethical and philosophical tests [sic], such as the Hobot ha-Lebabot of Bahye ibn Paquda, the Kuzari of Judah Halevi, Menorat Ha Maor of Isaac Aboab, etc.

During these early formative years, he learned not only classical Jewish texts but was read widely in many languages. Hakham Faur recalls, for example, having a discussion as a 12-year-old with R. Cohen, asking questions emerging from reading Charles Darwin’s The Descent of Man.

At the age of 17, the young scholar moved to Mexico City to serve as an administrator at a Talmud Torah. He stayed there for a year before enrolling in the Beth Medrash Govoah in Lakewood, New Jersey, reportedly one of the first Sephardic students to be admitted. The stories I learned about his three years there have a mythic quality to them. His knowledge of German meant that he quickly understood Yiddish, which allowed him not only to follow the Talmudic discussions but also challenge them. The story goes that Faur the student was so brilliant that even the rosh yeshiva, famed R. Aharon Kotler, recognized his sharp mind. (Hakham Faur’s ordination certification in 1962 noted that he had learned under R. Kotler.)

His time in Lakewood gave Hakham Faur an insider’s understanding of the methodology and intellectual tradition of the Lithuanian Haredi yeshivot. As he later remembered it:

The first lesson I heard by R. Kotler sounded like a revelation. ... He quoted a large number of sources from all over the Talmud, linking them in different arrangements and showing the various interpretations and interconnection of later Rabbinic authorities ...

My years in Lakewood were pleasurable and profitable. ... At the same time, the lessons of R. Kotler and my contacts with fellow students were making me aware of some basic methodological flaws in their approach. The desire to “short-cut” their way into the Talmud without a systematic and methodological knowledge of basic Jewish texts made their analysis skimpy and haphazard. On another, more personal level, I found the devotional attitude wanting and disturbing. The dialectics that were being applied to the study of Talmud were not only making shambles out of the text, but, what was more disturbing to me, they were also depriving the very concept of Jewish law, Halakha, of all meaning. Since everything could be “proven” and “disproven”, there were no absolute categories of right and wrong. Accordingly, the only possibility of morality is for the faithful to surrender himself to an assigned superior authority; it is the faithful’s duty to obey this authority simply because it is the authority and because he is faithful.

Even as he remembered R. Kotler with great respect, Hakham Faur came to challenge the learning methodology that characterized Lakewood and similar yeshivot.

In 1956, my uncle was invited to the geographically close but worlds apart Syrian community in Brooklyn to serve as a Torah teacher at Ahi Ezer Congregation, the Damascene synagogue.

When Hakham Faur entered the Brooklyn Syrian community at the age of 22, it had yet to experience its religious revival that introduced Torah learning on a massive scale. The community was led by an older immigrant generation of laymen, still speaking Arabic and by hakhamim who gave sermons in Arabic, such as the revered chief rabbi, Hakham Jacob Kassin, and the sage Hakham Matloub Abadi. Community members eventually hired American Ashkenazi rabbis, such as R. Abraham Hecht and R. Zvulun Lieberman, to cater to their English-speaking children.

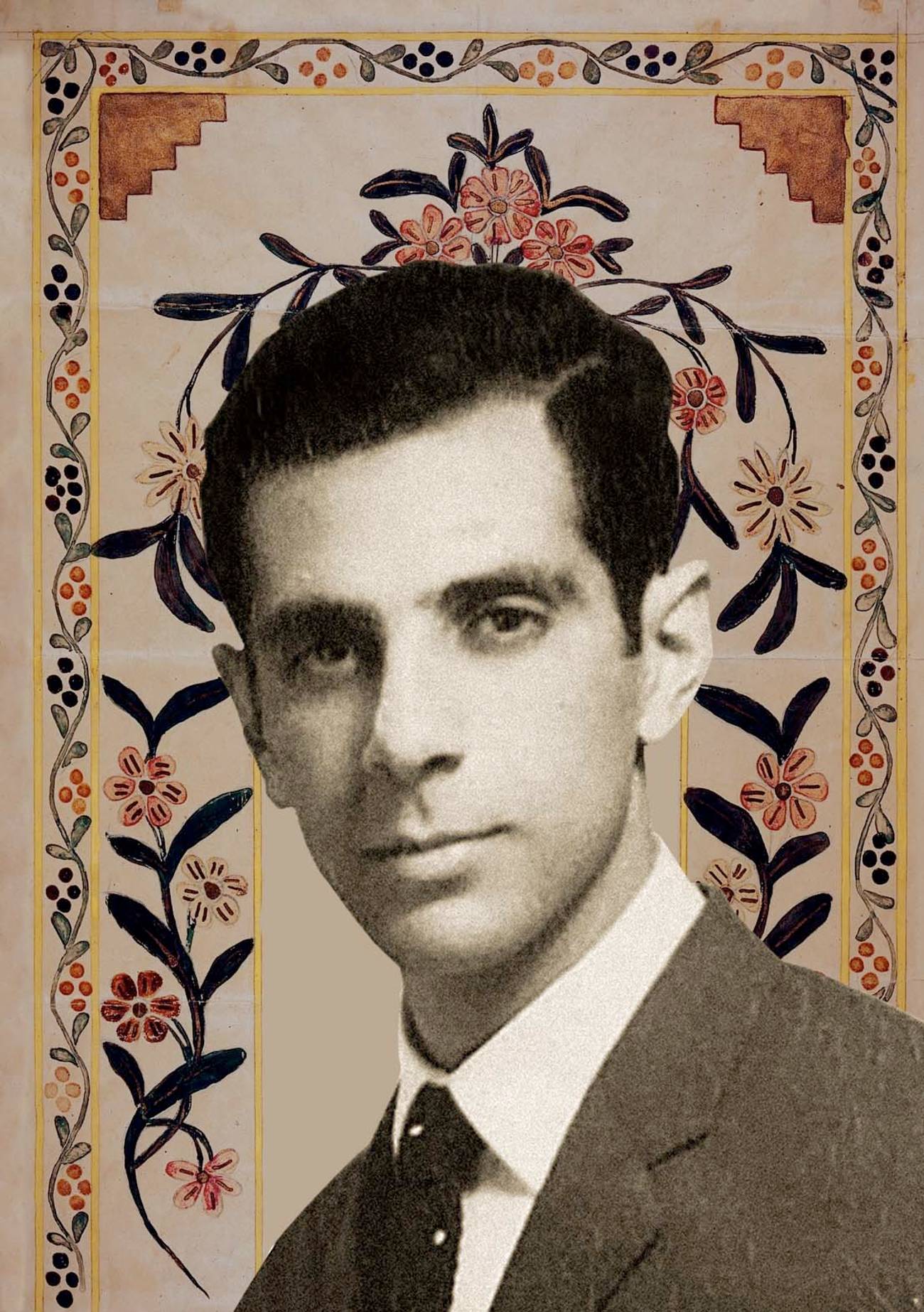

In this postwar environment, Hakham Faur made a name for himself as a proud Sephardic scholar who combined brilliance in Torah with a love for broader scholarly pursuits. Hakham Faur ignited a thirst for learning in a group of committed young Syrian men. In addition to scholarship, he introduced more punctilious Halachic practices such as keeping glatt kosher and dipping dishes in the mikvah. His students recall exhilarating conversations, learning daily from the More HaNevukhim, encountering Philo, Aristotle, and Einstein, exploring academic works on the Zohar, and learning the meaning of prayers they had muttered for years but never understood. They remember engaging in a Sephardic method of learning, such as studying the Bible with Ibn ’Ezra, not with Rashi as was the norm in Ashkenazi yeshivot.

A friend shared with me the words of her grandfather, who met Hakham Faur in the late 1950s. “Without Hakham Faur,” he said, “I would be a very very different person today.” This student attributed to Hakham Faur what many others still do: that he opened his eyes to the correct way of approaching Jewish tradition. My friend’s grandfather credits Hakham Faur not only for his knowledge of proper Jewish observance, but more generally shaping the trajectory of his life, even helping him get married.

Despite his quick success and at one point even gathering enough funds to purchase a building, Hakham Faur’s yeshiva did not take off. Some remember that there was not enough money to keep it afloat, others claim that disgruntled parents were unhappy with Hakham Faur’s leading their children to a lifestyle different from their families’. And yet others recall the more veteran communal rabbinic leadership looking with disfavor at the brilliant but young Hakham who saw himself their equal and even criticized some of them.

Hakham Faur argues that the rabbinic sages favored the dynamic world of language, metaphors, and analogies, rather than absolute idealism, magic, or hyperliteralism.

Hakham Faur then left the community and took a position at Harvard University as a librarian, hoping to get close to and study under famed philosophy professor Harry Austryn Wolfson, who persuaded Hakham Faur to inquire about the department of Semitics in the University of Barcelona. So, in 1959, Hakham Faur traveled to Spain, where he pursued his M.A. and Ph.D. in the University of Barcelona, the first Jewish student to matriculate there since the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492. There, he learned Semitic philology under Spanish scholar and historian professor Millas Vallicrosa, an expert in Hebrew studies, and professor Alejandro Diez-Macho, a Catholic priest and Hebraist. This area of study was particularly well-suited to him as he knew more than 10 languages and had a near-photographic memory. Furthermore, these studies complemented his other broad scholastic interests, such as in the history of science and philosophy.

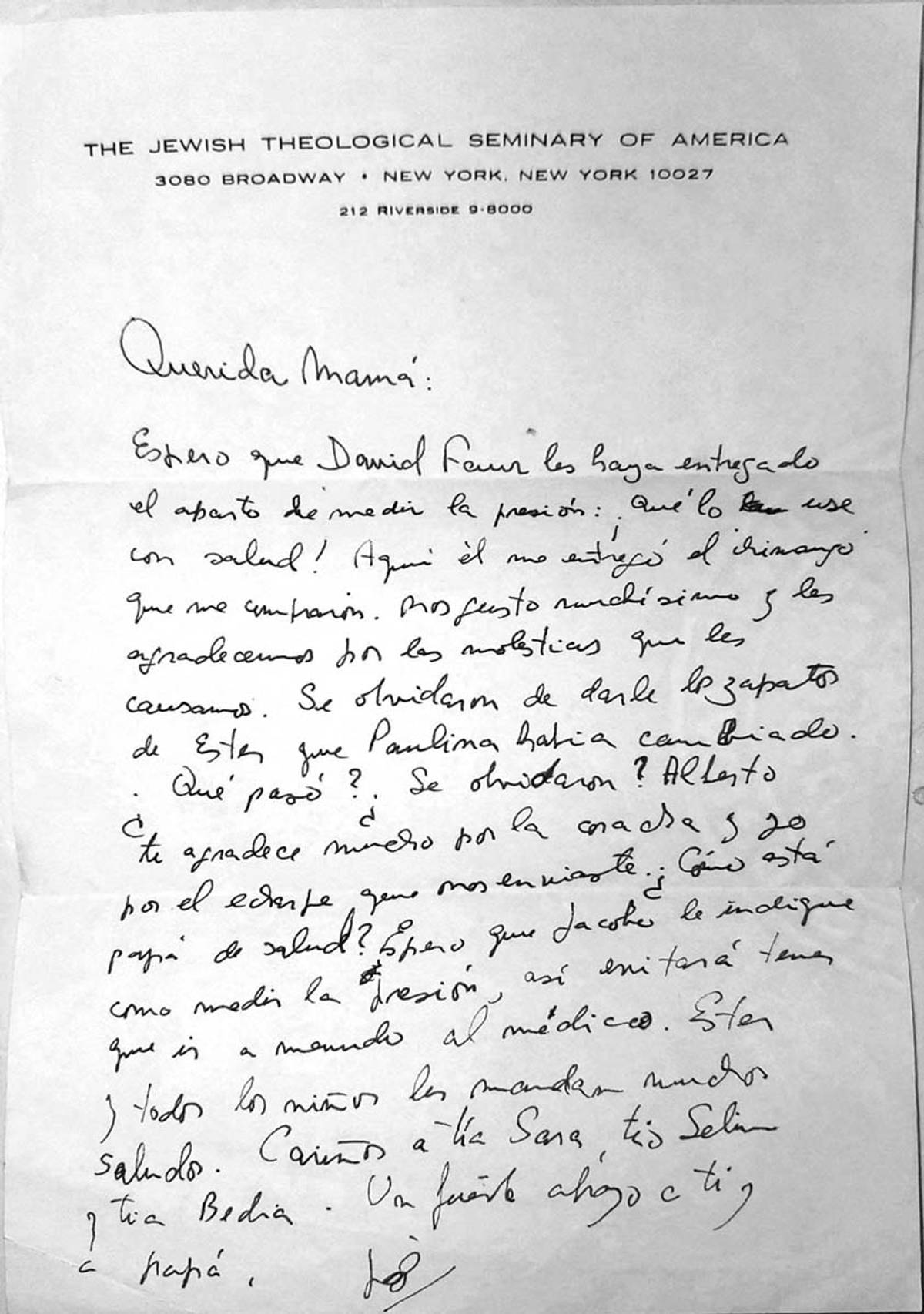

After his stay in Barcelona, Hakham Faur made his way to Israel where in 1962 he received his rabbinic ordination from the Sephardic Jerusalem Bet Din. In 1963 he married Esther, my great-aunt, and began building his family. Subsequently, an encounter with R. David De Sola Pool changed Hakham Faur’s trajectory. De Sola Pool, who was the rabbi of the Orthodox synagogue Shearith Israel, offered to help Hakham Faur secure a postdoctoral fellowship at the Jewish Theological Seminary (JTS).

Back in New York, Hakham Faur sought the blessing of his rabbi, Syrian community Torah leader Hakham Matloub Abadi, to work at JTS. With Hakham Matloub’s blessing, Hakham Faur served his postdoctoral fellowship at JTS and then became a professor focused on Halacha and Talmud, the first Sephardic faculty member since JTS was founded in the days of Sabato Morais and Pereiras Mendes.

At JTS, Hakham Faur enjoyed the companionship of intellectual giants such as professors Elias Bickerman, Saul Lieberman, and Abraham Joshua Heschel. A lifelong student of Hakham Faur from his JTS days recalls him being a popular teacher, with a “scintillating” style. His elective lectures in Halacha (Jewish law) rivaled in size some of Lieberman’s mandatory classes to the extent that he became a “guru” of sorts for those following him. This student—who eventually became a rabbi—recalls the first class he attended by Hakham Faur, which focused on the Talmudic tractate of Mo’ed Katan and which my great-uncle used to introduce his students to rabbinic methodology. He wanted, Hakham Faur said, to empower his students to learn how to read the Talmud, how to have the proper training and methodology to have independence in understanding rabbinic texts and not needing another authority as their conduit to Jewish texts. As a teacher, he was both demanding and generous. “He taught with great care, choosing every word precisely and empowering the student’s methodology.”

Even as he was working at JTS, Hakham Faur was involved with the Syrian community in Brooklyn where he retained students and learned with Hakham Matloub Abadi who granted him Dayyanut (Even Ha’Ezer) in 1966. (He was granted Dayyanut on Hoshen Mishpat by Hakham Soleiman Huggi ’Abbudi in 1968.) Some of those students became his lifelong supporters.

It is here, in the 1960s, that the historical record gets increasingly fuzzy, partially because it is still contested by people who lived through it. Hakham Faur had been hired as a teacher in Congregation Shaare Zion where he gave classes, which were increasingly popular with young people. A Syrian Jewish businessman who was a college student at the time recalls Hakham Faur as a charismatic and magnetic orator, not only a scholar. “I always found his Torah classes to be inspiring, educational and beautifully put together,” he said. But despite his success, Hakham Faur began to be haunted by rumors and accusations of heresy. These accusations were doggedly pursued; they originated from within the community and centered both on his ideas and on certain Halachic opinions he held.

These accusations of heresy evolved into a significant battle in the community—a battle that raged for decades and that still echoes today—between Hakham Faur’s supporters and his detractors. At one point, R. Jacob Kassin and Hakham Matloub Abadi investigated and exonerated Hakham Faur, but the accusations persisted, many of them led by R. Baruch Ben Haim, R. Kassin’s son-in-law.

One key argument in the accusations against Hakham Faur was that he was then teaching at JTS, a Conservative seminary. R. Abraham Hecht, the rabbi of Congregation Shaare Zion, eventually utilized a teshuva by R. Moshe Feinstein to forbid Hakham Faur from continuing to teach Torah at Shaare Zion. Hakham Faur, who claimed that his work at JTS was his way of providing for his family, continued teaching informally in the Syrian Jewish community, in homes and rented halls.

In conversations with men who remember those years they describe his classes as intellectually thrilling. My great-uncle’s teachings were characterized not only by his biting sense of humor and powerful oratorical style but by a desire to always find a hiddush, a novel way of reading text. Hundreds of people flocked to learn in packed halls from a teacher with a level of erudition, breadth of knowledge, and creativity unmatched. But still, the rumors and communal infighting persisted.

Eventually, when JTS decided to start ordaining women, Hakham Faur resigned in protest. He then sued for breach of contract, arguing that by ordaining women JTS was constructively terminating his employment. After his resignation, he was again considered “kosher” enough for the community and deliberations began as to whether he could teach again in Shaare Zion.

While that was going on, a small group of men decided to open a new synagogue, Bnei Yitzhak, a few blocks away, where Hakham Faur would be the main rabbi and teacher. Eventually, Shaare Zion’s executive committee hired Hakham Faur to lecture on Tuesday evenings, classes that had between 150 and 250 attendees regularly. Hakham Faur’s official reentry into community institutions spurred even more accusations of heresy.

Some of the protagonists of what was mainly an internal community fight, resorted to invoking famous Israeli rabbis such as R. Ovadia Yosef, R. Mordekhai Eliyahu, R. David Shlush, R. Shalom Messas, R. Yosef Messas, and others. A formal rabbinic tribunal comprised of Sephardic hakhamim including R. Mordechai Eliyahu and R. Shalom Messas investigated and then cleared Hakham Faur’s name.

But the opposition to Hakham Faur gained more traction, especially once he began lecturing in Shaare Zion. This culminated in the publishing of the 1988 letter and Hakham Faur’s eventual departure from the community.

Leaving the Syrian community—and its battles—behind, Hakham Faur made his way to Israel. There, he was able to dedicate himself to writing, publishing over his life nine books and more than 100 articles. He told one of his close students that he was grateful for this time, away from intracommunity battles, in which he could dedicate himself to learning and teaching his beloved Torah. One of his younger students who learned from Hakham Faur in Israel remembers not only my great-uncle’s brilliance but also the way he shaped a transnational community of students seeking to learn his Torah. He said:

I always felt his attachment to younger students when I was with him. When I would come ask him a question and someone else was also around, he would always point to me how much of a talmid hakhamim (student of sages) the students around me were and that there is a lot to learn from them. He would try to remove the focus from himself to lift up these younger students and give them confidence in their own stature to encourage their own studies.

Hakham Faur’s biography is not incidental to his copious body of work. Beyond personality traits or communal politics, there was something about his intellectual project that was incompatible with that of many of his contemporaries. It is this project, his attempt to revive Old Sepharad, that I will attempt to describe.

One of Hakaham Faur’s earlier works was written, he describes, in a furious month of writing aimed at preserving the memory of an intellectual tradition in danger of extinction. This work, Rabbi Yisrael Moshe Hazzan: The Man and His Works (1978), centers on a Sephardic hakham, Turkish Rabbi Yisrael Moshe Hazzan (1808-1862), and lays out a Sephardic approach to Judaism.

Reading Rabbi Yisrael Moshe Hazzan feels revelatory in a way emblematic to Hakham Faur’s work, which is regularly filled with names of Sephardic intellectual giants who have been lost to oblivion. Who has heard of luminaries such as Italian physician Hakham David Nieto, or R. Yehuda Bibas, a Sephardic proponent of political Zionism? Hakham Faur made a point to not only mention them by name across all his works, but also to cite their conceptual contributions and works when presenting the systematic approaches to Torah of Old Sepharad. He was intent on not only reviving them from the obscurity of long-forgotten history, but also reviving their relevance as champions of an intellectual tradition.

At the heart of this book is a novel claim. Hakham Faur argues that sages such as R. Hazzan represent a unique Sephardic response to modernity that has been largely forgotten. While many Western Jews responded to the Enlightenment and Emancipation by abdicating Jewish nationalism and adopting Judaism as a religion, Sephardic hakhamim largely refused to do so. Hakhamim like R. Hazzan wanted to be involved in the intellectual world around them but not at the expense of their own self-understanding, mainly that to be Jewish is to be a member of a nation.

Sephardic hakhamim, according to Hakham Faur—such as R. Hazzan and R. Eliyahu Ben Amozzeg, embodied a Sephardic religious humanism—in the spirit of Enlightenment Italian humanist Giambattista Vico, and English father of scientific inquiry Sir Isaac Newton. This religious humanism stood in contrast with a rational secularism, which sought to strip God and tradition of their authority. The novelty of the approach of these Sephardic sages is the confident insistence that tradition must have a seat at the table of modernity.

Throughout his writings Hakham Faur contrasted this Sephardic orientation with other—according to him—flawed ideologies and methodologies. His polemical writings remind me of the way he described his childhood, growing up in a mostly Catholic Buenos Aires. He wrote:

In those days everyone attended public school. The atmosphere was heavily Catholic, and terribly unsympathetic to anything remotely “Jewish”. We had to learn fast how to survive. In a sense, some of us felt like our forefathers in Christian Spain, trying to maintain a Jewish identity and develop in a hostile and suffocating environment.

These experiences, Hakham Faur says, helped him “survive Jewishly” when he matriculated at the University of Barcelona. This defensive combativeness—the fight to “survive”—can be sensed in his work and can be understood as reflecting his belief that his beloved Sepharad was in danger of extinction. In one of his earlier books, In the Shadow of History (1992), Hakham Faur shows the incompatibility between the Christian and Hebrew traditions, and what inner reasons were underwriting the strong and irreconcilable animus and persecution of Christian Spain toward the conversos.

Hakham Faur also recalls being “isolated” as a child from the Ashkenazi community in Argentina where casual contact never “develop[ed] into friendship or a meaningful exchange of ideas.” In his later works, like in articles analyzing the legal thinking of the tosafists, Hakham Faur reveals a consistent critique of the methodology and tradition that are prevalent today in Ashkenazi-Lithuanian yeshivot. He believed that the environment in which much of Ashkenazi history unfolded was deeply Christian and thus both irreconcilable with rabbinic Judaism and politically totalitarian. For Hakham Faur, the conceptual approaches of Jewish rabbis from Christian environments were generally not immune to Christian affect, and therefore, unlike Old Sepharad, not infrequently at odds with fundamental aspects of classic rabbinic Judaism.

The seminal idea that most fundamentally guided my great-uncle’s intellectual project of reviving Old Sepharad is that of “Alphabetic Judaism.” Hakham Faur argued that in contrast with a reality that is, according to the Jewish perspective, reality is a text that “means” and that God is its Writer. This semiological approach to Judaism, Alphabetic Judaism, conceives of Jewish tradition and reality at large as texts that human beings are capable of reading.

Although Hakham Faur described this approach borrowing terminology from modern semioticians like Ferdinand de Saussure, Roland Barthes, and Émile Benveniste, he identified this approach with traditional rabbinic literature and its heirs from Old Sepharad, and in particular with Maimonides. He often argued that the very essence of the Hebrew language, a language written as unvocalized consonants which must necessarily be vocalized by the reader, is emblematic of a society that believes in active and uncoerced reading.

The alternative, analphabetic Judaism, approaches reality as a static ontological dimension that “is,” with God as its predictable prime mover (or “Mother Nature”) and humans as if in a quest to uncover the ultimate truth. Less explicitly, he identified this approach with most Western intellectual tradition: Christian, secular, and Jewish. From Plato to Hegel, from Christianity to Islam, from Aristotle to modern physicists (quantum physicists excepted), and from Nachmanides to Rav Kook: All these thinkers and theologians believed there is an ultimate truth somewhere in the ether and that it is humanity’s great calling to discover it.

Hakham Faur believed that the most important trait of human beings is the ability to interact through symbols: A first person encodes some idea in the form of a symbol, and submits such symbol to the second person so that this second person “decodes” this symbol by generating another idea in this second person’s mind. This is the exercise of reading. One key point is that once an idea is encoded into a symbol, the first person no longer controls it, and it is the second person who is tasked with generating meaning by interpreting it.

If the operating systems of the first and second persons are sufficiently aligned, then this exchange of symbols and mutual generation of meaning results in a dynamic dialogue, uncoerced, and capable of resulting in more than one “true” meaning. If these commonalities do not exist (say, if the first and second person don’t agree on the universe of things that can be signified by the color pink), then communication is impossible.

From the nine books Hakham Faur got to publish (I understand he left several manuscripts in various states of completion that have yet to be put in print), I can offer a description of three of his works that investigate semiotics and Judaism, reflecting his construction of alphabetic Judaism.

The first, Golden Doves with Silver Dots (1986), explored the similarities between the analytical methods of structuralists and post-structuralists, and the rabbinic sages’ approach to language and reality. It set out the fundamentals for Hakham Faur’s subsequent works touching upon semiotics and Alphabetic Judaism. The book argues that reading, in contrast to discovering, is the preferred mode of Jewish epistemology. It shows that for the rabbis, reality was a semiological system rather than a metaphysical one.

In this work, Hakham Faur argues that this was indeed the way the rabbinic sages understood the Torah: The prophets, Philo, Joséphus, the tannaim, the amoraim, the geonim, and their ideological heirs in Spanish Andalusia (most notably Maimonides), all favored the dynamic world of language, metaphors, and analogies, rather than absolute idealism, magic, or hyperliteralism. Derasha was a form of active reading, not static discovery. Rather than trying to find the “absolutely true” meaning of a text, rabbinic derashot were an exercise of engaging with a signifier and generating a signified from it, and the rabbis were at ease with the resulting verisimilitude of this approach.

My great-uncle emulated this method in his own teaching. So many of his students have told me that he always demanded to hear from them hiddushim (new interpretations) in Torah. One of them recalls the following anecdote:

I once shared a realization I had on a certain topic with the Hakham, noted how it had been implicit in several of our past classes and discussions, and asked him why he had not “taught” it to me before. The answer changed my life: if he had “taught” it to me earlier, I would never have “learned” it.

In Golden Doves Hakham Faur insisted that critical theory must inform Torah and Torah must inform critical theory. This, Hakham Faur could do because he was at home in classic rabbinic Judaism and also in the intellectual realms of poststructuralism, deconstructionism and semiotics. To this, he added other intellectual advantages: native knowledge of Judeo-Arabic, fluency in Arabic philosophy and theory, and comfort within the rabbinic and Sephardic exegetical and hermeneutical traditions.

Hakham Faur’s creativity was most obvious in his ability to build layers of meaning through the juxtaposition of diverse works: reading Paul Ricoeur, Jorge Luis Borges, and Jacques Derrida in the verses of the Hebrew Scripture, the Mishna, the Talmud, and the vast corpus of intellectual industry produced by sages representing Old Sepharad since Talmudic times. The late professor Jacob Neusner, with whom Hakham Faur was friendly, described the way this work reads rabbinic Midrash within contemporary literary theory and semiotics as an exercise in cultural mediation.

Golden Doves stands in contrast to most works in the academic study of Judaism, which approach Judaism as an object of study, and not as a living tradition that has internal systems that must be respected. Hakham Faur’s approach also differed from the pilpul-like method common to many yeshivot—in which extrapolation of creative ideas are often prized over a punctiliousness with Hebrew grammar, with having the right texts, and understanding the proper process for decoding of classical texts. There, too, Hakham Faur argued, the pilpul is trying to solve for the static metaphysical truth.

Homo Mysticus (1998) was according to many of Hakham Faur’s students his most profound contribution. In this work, Hakham Faur offered a novel analysis of pre-Kabbalah rabbinic mysticism through a study of Maimonides’ Moreh Nevukhim, a book that he learned in its original Judeo-Arabic. As opposed to viewing Maimonides as an Aristotelian rationalist, Hakham Faur saw him as a traditionalist who inherited the mantle of the rabbinic tradition and engaged with Greek knowledge without ceding the assumptions underlying his own tradition. In other words, Maimonides was a hakham, not a philosopher.

In this work, Hakham Faur argues that rather than discovering God’s true essence (which, rabbinic Jewish tradition maintains cannot possibly be known by human beings), the Jewish mysticism of Maimonides consisted of distilling one’s perceptual abilities to a point where God’s speech can be processed with as little noise as possible. Whatever “word” God utters (be it a galaxy, a flower, a single cell, or a passage in Scripture) is not nearly as important as the level at which the perceptual experience is taking place, or to what extent the person perceiving—reading—such divine utterance is subsequently transformed.

Homo Mysticus resembles—structurally—Maimonides’ own guide. Hakham Faur believed the Guide itself concealed its true teachings in its pages and as such wrote his own interpretation of the Guide in a similarly cryptic way. Serious students of Homo Mysticus have mentioned to me that it is a book to be studied; not a book to be read. For Hakham Faur, the textual medium cannot be disentangled from its meaning. Homo Mysticus suggests that the highest form of individual experience is defined by the medium, more than by the content.

A focus on methodology that allows fluency in the medium, his students told me, was emblematic of Hakham Faur as a pedagogue. A Syrian community leader and lawyer who had been learning from Hakham Faur since the 1970s describes him as continuing the path of teachers in Sephardic tradition, as a “landscaper” of students’ brains, “making sure that the fertile soil is properly nourished, cultivated, and weeded” with the basics needed for independent learning. This “mental cultivation” was based on a pedagogical assumption that methodology was key and that students can only be empowered once they are taught the basics.

In The Horizontal Society (2008), Hakham Faur synthesized many of his past ideas and presented a holistic description of what he maintained was the People of Israel. Most importantly, he laid bare how his semiological approach to an alphabetic Judaism is a deeply political one.

In this work, Hakham Faur builds on the notion that Judaism is not a religion, that it is a nation. As such, it has a constitution (the Torah), a legislative body (the Sanhedrin), national memory, national symbols and national institutions. Attempts to challenge the Torah of Israel are thus not just theological or intellectual disagreements but political attacks.

The People of Israel, suggested Hakham Faur, achieved a quantum leap in human development. Instead of claiming that they had discovered the ultimate theological truth (or that they knew the Natural Laws), the People of Israel claimed to have been privy to a dialogue with God. A God who could read and write and who could communicate. A God who could never be discovered— unknowable to humans—but who communicated in symbols to be read.

Perhaps the most important idea in Horizontal Society is that of covenant, that the relationship between the Jewish people and God is a legally binding covenant that is a function of a bilateral dialogue. This relationship was revolutionary since it was not coercive. The Torah was not dictated in the third person by a magic deity sitting atop a pyramidic hierarchy. It was offered in a dialogue, first person to second person, where the People of Israel were free to accept or reject it; where agreeing to engage in this dialogue also meant that the second person, the People of Israel, had the right and responsibility to generate meaning on the symbols uttered by God.

Hakham Faur maintained that the society resulting from such a system would be the pinnacle of political evolution: a horizontal society where the governing principle is dialogue and where equality is a function of subservience to an agreed-upon law. The Hebrew king, the priests, the prophets, the rich and the poor, and even God Almighty, all are seen in Jewish tradition as being equally bound to the covenant.

What Homo Mysticus suggests on the potential of the individual, Horizontal Society does with respect to the national. Horizontal Society explains what the People of Israel is designed to be, where they excel and where they have thus far failed.

As such, for Hakham Faur, the law—God’s text—is essential for political freedom. It is the absolutely supreme standard in reference to which all else finds horizontality. Any attempts, thus, to try and wedge a gap between the people and the law are tyrannical, and often motivated by tyrants seeking personal power. More specifically, any intermediary—a divine monarch or mystical rabbi, say—who claims the ability to uncover divine truth due to their persona is committing an act of political oppression.

In his own teachings Hakham Faur reaffirmed this message over and over: He did not want his students to see him as some sort of infallible religious authority that should tell them what to do and how to think. One of his lifelong students, a community rabbi, recalls the one time that he found a mistake in one of Hakham Faur’s ideas—something related to te’amim. Despite being a “very demanding teaching who would flatter you maybe once in a blue moon,” Hakham Faur, he told me, “was visibly happy that I, one of his many students, got to correct him in this minute detail and immediately changed the draft he was writing on the subject.”

Reflecting on my great-uncle’s towering intellectual legacy, one that this essay barely begins to encompass, I am above all grateful that he succeeded in reviving a Sephardic legacy that without him would have largely been forgotten.

But even as I learn thirstily from his Torah I am aware that I have chosen a different path. My own ideas have been shaped in light of encounters with other communities and cultures. I live in the intersection of the liberal West and traditional Judaism, find a foothold in feminism and in Middle Eastern Jewish identity. I engage less in study of classical texts delimited by an interpretative tradition with a clear and consistent methodology and more in the exchange of pluralistic ideas in mostly Ashkenazi communities.

At times I worry whether my path reflects a lack of confidence to be the heir to the Sephardic Judaism I was taught. What would my life have looked like if I had received the same education as my brothers when I approached my tradition as a young girl? Mostly, I believe—and hope—that my own disposition and meanderings through life have led me to an alternative path. I have realized, as well, that my great-uncle’s path represents a different type of accessibility. In an age of identity politics when identity reigns and gives people the right to speak, Hakham Faur shifts the axis upon which we imagine the Torah’s inclusivity: It is available to anyone willing to dedicate their lives to decoding the symbols of Torah, to struggling through Hebrew dikduk and Talmudic methodology, through learning hermeneutics and biblical peshat.

My great-uncle was a genius talmid hakham, not afraid to stand alone if he thought his path had integrity. He was a contrarian and a lonely man of faith not because his mind was contorted with existential contradictions. His loneliness was the result of standing alone in the bet midrash of Old Sepharad knowing that his fellow readers were sages who belonged to mostly forgotten generations. His tremendous output reflects his desperate determination to ensure that the legacy of his Sepharad should live on.

I imagine my great-uncle now in the heavenly bet midrash learning Torah with the sages he so loved, joyfully arguing over divine letters. His words, however, remain on Earth. To be read and argued over and generate new meaning and readers and writers and links in the great chain of transmission of Old Sepharad.

Mijal Bitton is a Fellow in Residence at the Shalom Hartman Institute and the Rosh Kehilla of the Downtown Minyan.