The South’s Greatest Jewish Poet Strikes Zen Gold

A visit with Hank Lazer in Tuscaloosa, wondering ‘what is a Jew doing here’

“I’m a Jew and a Buddhist living in the Deep South. I feel compelled to define what that means. If I lived in Brooklyn I wouldn’t have needed to affirm that,” said poet Hank Lazer early this year, smiling, as we sat in the cozy, colorful study at his home in Tuscaloosa, Alabama. If Brooklyn and Berkeley are the diaspora, then Tuscaloosa, one would imagine, is the diaspora’s diaspora, a designation that is less physical than poetic and spiritual, a place where identity is inevitably dialectical. As Lazer told me, it was in Alabama over the past few decades that he found himself “turning toward phenomenology of the spiritual experience … not a fixed-state thing but a kind of oscillation, movement in and out of spiritual awareness of something that matters, something other than our specific, superficial identity.”

Though it was my own first visit to the so-called Deep South, the poet’s study, in which we conducted the interview, was familiar: Lazer had previously Skyped with different groups of my literature students in California, and had given readings to them across the digital space. I have been following and teaching Lazer’s work, attracted to its contradictions, which so naturally lend themselves to complex, creative conversations with students: His poetry is unapologetically spiritual, yet nondogmatic. It is deeply intellectual yet is written in a manner that’s entirely accessible. And Jewishness is central to it but so is the author’s sense of being in the margins of the community.

My plane landed an hour’s drive away, in Birmingham, known for its role in the Civil Rights Movement. Tuscaloosa itself is a university town: clean, simple, and diverse in its population. All through my stay, I kept looking for markers of difference. More than anything else, though, I kept noticing space: between houses and structures, in Lazer’s backyard, around the meandering path overlooking a pond, between tables in a restaurant. Although late winter is as warm in Alabama as it is in the Bay Area where I live, the air felt different—crisper and fresher.

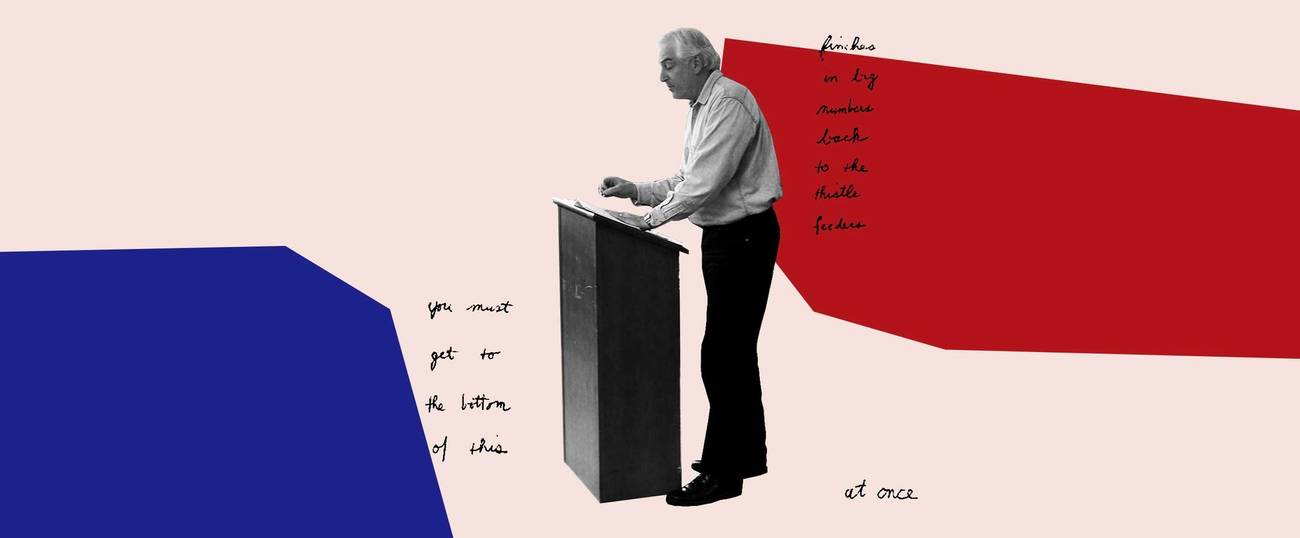

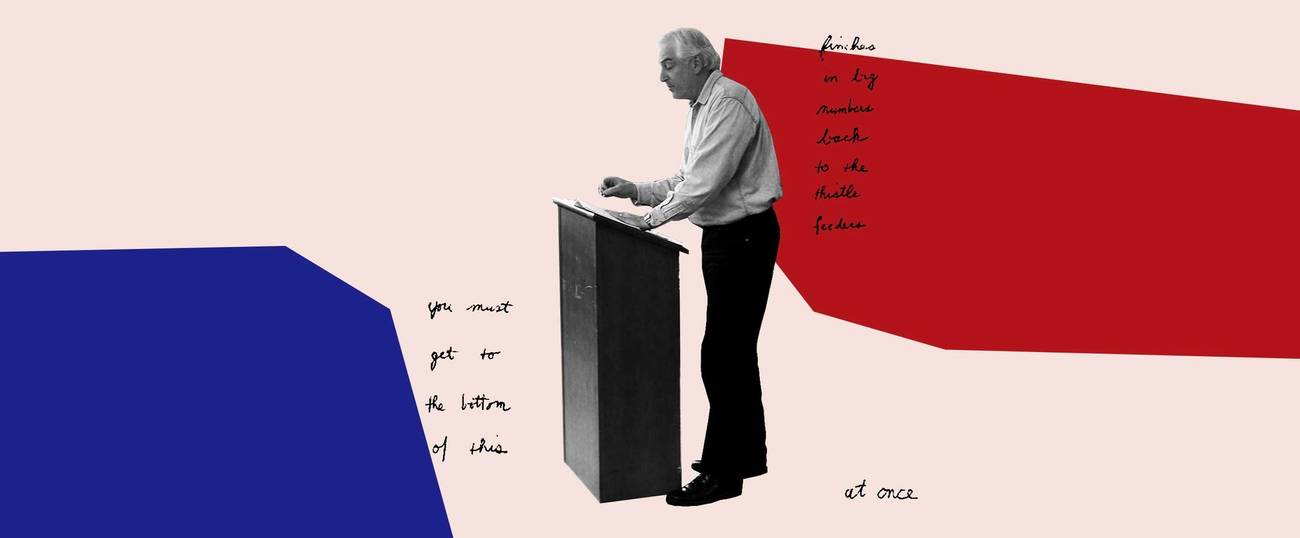

Lazer is tall, gray-haired, and, these days, bearded. He speaks with deliberation, freely switching dialectical registers—sounding at times Californian and at other times Southern. And Yiddish-flavored expressions pop up as well, particularly when he quotes his grandmother Fanya, a formidable early influence. Born in San Jose, California, grandson of Russian Jewish immigrants, Lazer came to Tuscaloosa more than 40 years ago, following the completion of the doctoral program, to take a job as a professor of English. Following a number of contentious years in the department—colleagues did not appreciate his interest in experimental literary theory and poetics, he said—he worked in the university administration, while teaching courses here and there for pleasure, and writing in the evenings and on weekends. He is now the author of nearly 30 volumes—poetry collections, chapbooks, and critical essays. In the past year, three new books of his came out: Slowly Becoming Awake (N32), Poems That Look Just Like Poems, and Brush Mind 2: Second Hand.

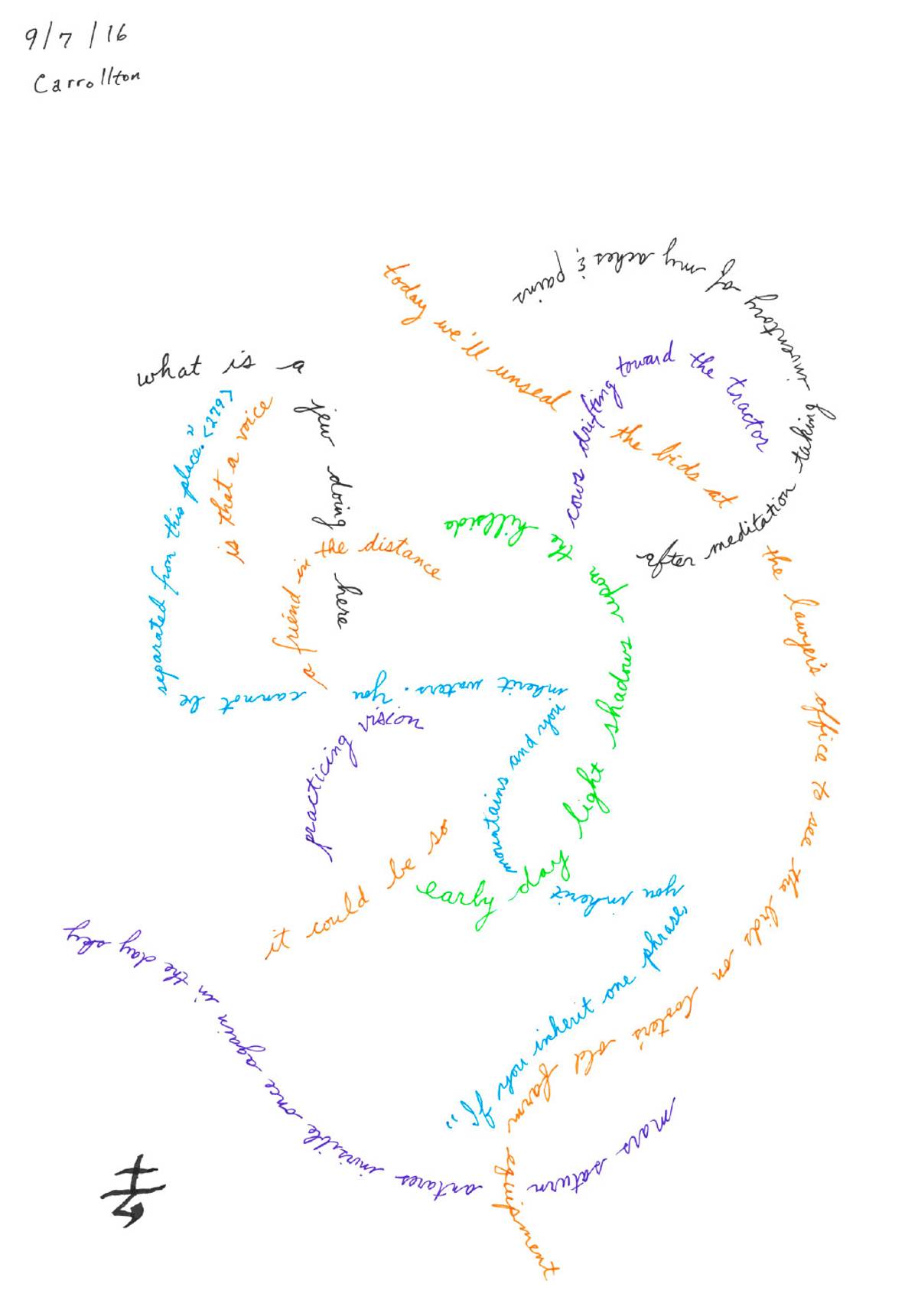

Together, we examined a poem I selected from the Slowly Becoming Awake collection. Like all other works in this volume, it does not have a title and is what Lazer calls “shape writing”: a handwritten work in which lines move across the page in spontaneous, intersecting shapes. Like most other poems in the collection, it contains a quote—in this case, from the 13th-century Japanese Zen master Eihei Dogen’s masterpiece Shobo Genzo.

The poem does not have a set beginning or end, and in that way, is always an improvisation, an ongoing and inconclusive engagement. Gertrude Stein’s quip comes to mind: “one naturally is impressed by anything having a beginning a middle and an ending when one … is emerging from adolescence.” Perhaps, this kind of a poem, then, is more mature, or in any case in touch with life’s expansiveness, and the endless layers of reality—social, intellectual, psychological, personal—which, rather than starting and ending, intersect and shift in and out of larger contexts. When Lazer reads the poem out loud, he starts with “it could be so”—and reads on curiously and slowly, as a reader, rather than author, musing on possibilities.

The phrase “what is a jew doing here” angles downward through the observation “is that a voice/a friend in the distance.” The lines feel experiential rather than cerebral: I envision a narrator, who, while contemplating his place in the world, is interrupted by the voice of a neighbor. Or is this about questioning a voice in one’s own mind, the one that asks, in the voice of one’s grandparents: “What’s a Jew doing all the way out here?” Is the “friend” of this poem someone nearby—or is it a call from within a memory, or another poem? Simple phrases are, as Lazer said, “intervals of consciousness”—caught in complex networks of meaning.

The key question the poet tackles can be articulated as: “what is human embodiment, incarnation of consciousness is like—now—can you make that manifest?” The poem doesn’t describe or conjure consciousness, but demonstrates, notates it, and mines it for auspicious, mysterious insights. Thus, Dogen’s quote, about inheriting another’s language, comes from Lazer’s reading, and is, on the one hand a metapoetic insight that points to the “inheritance” of Dogen’s very phrase and his line of thought, by Lazer’s poem. On the other hand, the text also refers to Cooter, a relative by marriage from whom Lazer inherits farm equipment, as the work alludes. And of course, the inheritance of experience occurs when a careful reader engages with the poem.

As the upper left corner of the page indicates, the poem takes place in Carrollton, on a farm, not too far from Tuscaloosa. The idea of the place—in this case, a very specific place—is crucial to Lazer. A great deal of experimental poetry is focused on the abstract life of ideas and the mind, often divorced from lived experience. And as readers, from high school and through college, we are trained to forget author’s circumstances for the sake of the text’s openness. But encountering Lazer, seeing the poems through the lens of our interaction, I am moved to think just how important that interaction is, how it deepens the meaning of the poem without trivializing it with biographical connections.

***

Accompanied by Lazer’s wife, Jane, and his son Alan, we went to a hip Tuscaloosa restaurant, with high, almost church-like ceilings and exposed brick walls. An acoustic trio performed an eclectic mix of folk, punk, and blues. People waved to each other across the tables. The maître d’ stood chatting with the band between songs. A constant stream of people stopped by our table to say hello. Lazer was clearly at home here, and yet, when a few years ago he received the Harper Lee Award, an Alabama literary prize, he said that it was “a total shock … a profound moment of acceptance as an Alabamian, as a Southerner.”

Perhaps because Lazer touches upon multiple social and intellectual circles, his poetry is strikingly accessible. As he told me, he attempts to rid himself of the “poetic MSG … adjectives, adverbs” as he moves “through different registers of language” toward a kind of clarity. His latest collection, Poems That Look Just Like Poems, are, in their presentation, nothing like the shape poems. They do indeed look like poems—packed into a small, pocket-size volume. One titled “Integrity” stands out:

because it cannot

be taught

it matters

a way

of thinking

that refuses

to reduce thinking

to a set of learned

characteristics

because it can

not be other than

the infinite

complexity of

being itself

there is nothing

specific to be

learned nothing

to teach

& repeat

this is what

i mean by

pleasure

or

integrity

Whatever we may understand the poem’s “it” to be—the meaning of life, thinking, holiness, interconnectedness—one can never be adequately prepared for the encounter. This sacred “it” cannot be articulated in words, let alone be taught, or explained. And yet, the poem states, precisely because it cannot be taught, or even articulated, it is important. Normally, “pleasure” and “integrity” do not go easily together: As the former is marked by the lack of self-consciousness, the latter implies a keen awareness of the rules. But, perhaps, when it comes to the poem’s mysterious “it,” they’re one: Dedicating a life to the invisible is a matter of one’s own integrity, yet it is also a great pleasure.

As we sat in Lazer’s living room, decorated with the vibrant paintings of New York artist Susan Bee, we spoke about poetry and poets: about Lazer’s recent jukai—Buddhist lay ordination ceremony, officiated by Lazer’s friend, poet, and Buddhist priest Norman Fischer. We spoke about the spiritual life, and told old Jewish jokes. But we also spoke about Lazer’s three dogs—Nate, Emmy, and Walt—and their personalities, their grace. Pointing to his youngest pup, Lazer said: “When Nate runs, he’s so excited he’s barely touching the ground.” I watched Nate bounding in the backyard, where big bird feeders stand.

On the plane home, one of Lazer’s insights came to me: “I tend to think of the poem as a portal … I may be writing but I’m not the only one there … others are co-present with me—people I’m close to in this amorphous, spiritual poetic practice … feeling them being there.” Sounds mystical, but perhaps like all true mysticism it is rooted in something very real—in the warmth, openness, and desire to engage.

Jake Marmer is Tablet’s poetry critic. He is the author of Cosmic Diaspora (2020), The Neighbor Out of Sound (2018) and Jazz Talmud (2012). He has also released two jazz-klezmer-poetry records: Purple Tentacles of Thought and Desire (2020, with Cosmic Diaspora Trio), and Hermeneutic Stomp (2013).