Hannah Arendt’s Critique of Social Media

How personal judgment—essential to a diverse democratic public sphere—gets subsumed by our clichéd attempts to join the crowd

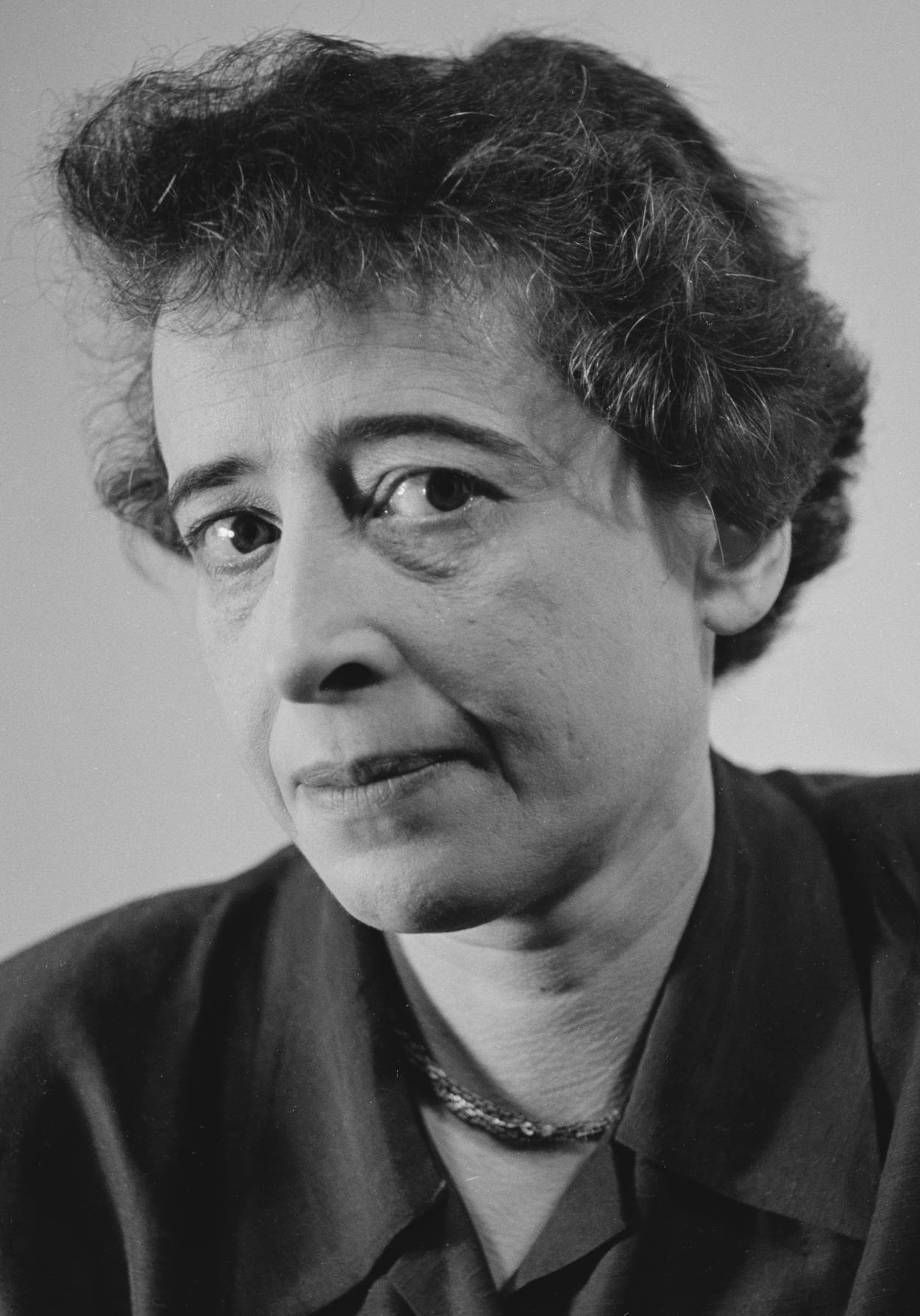

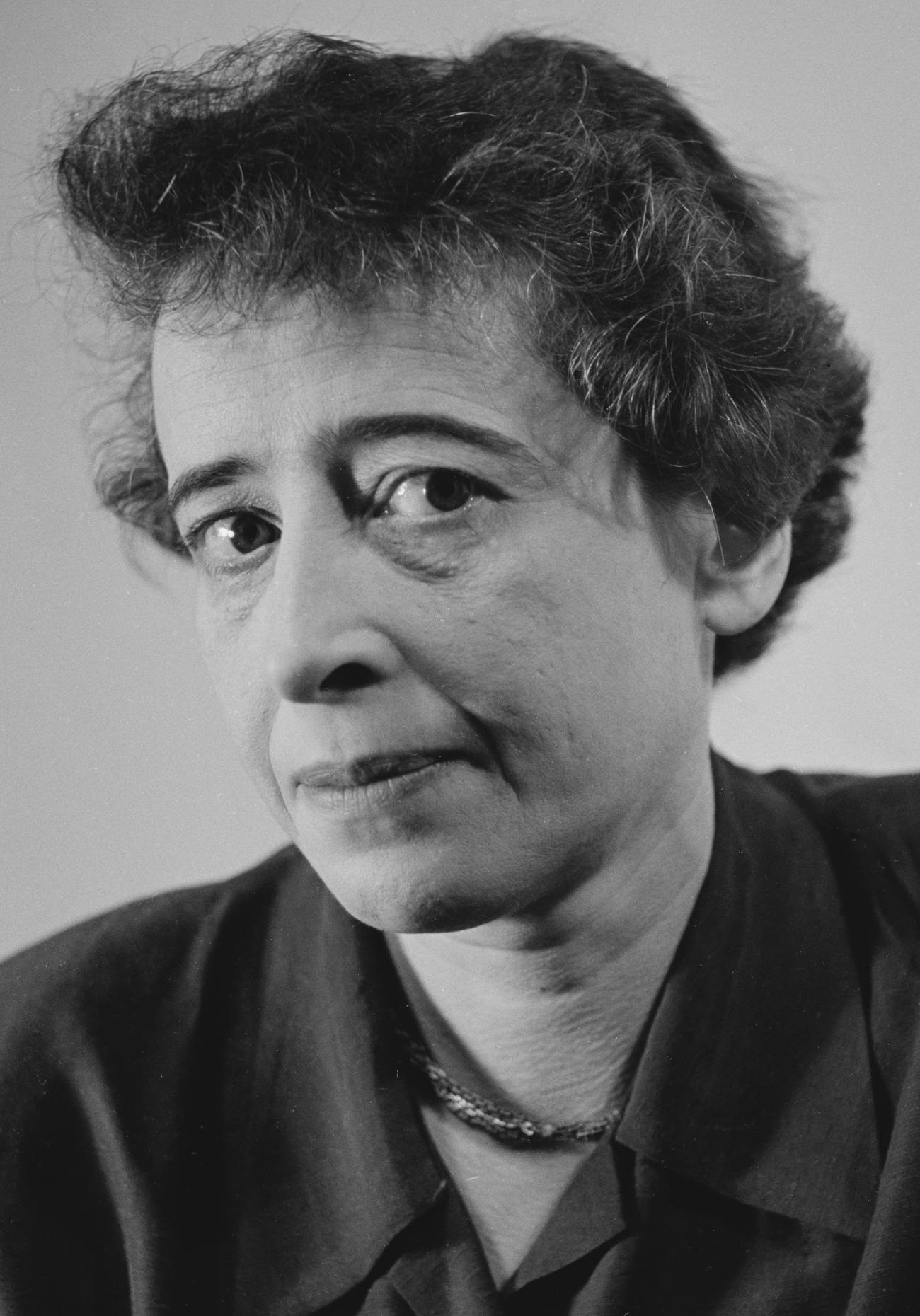

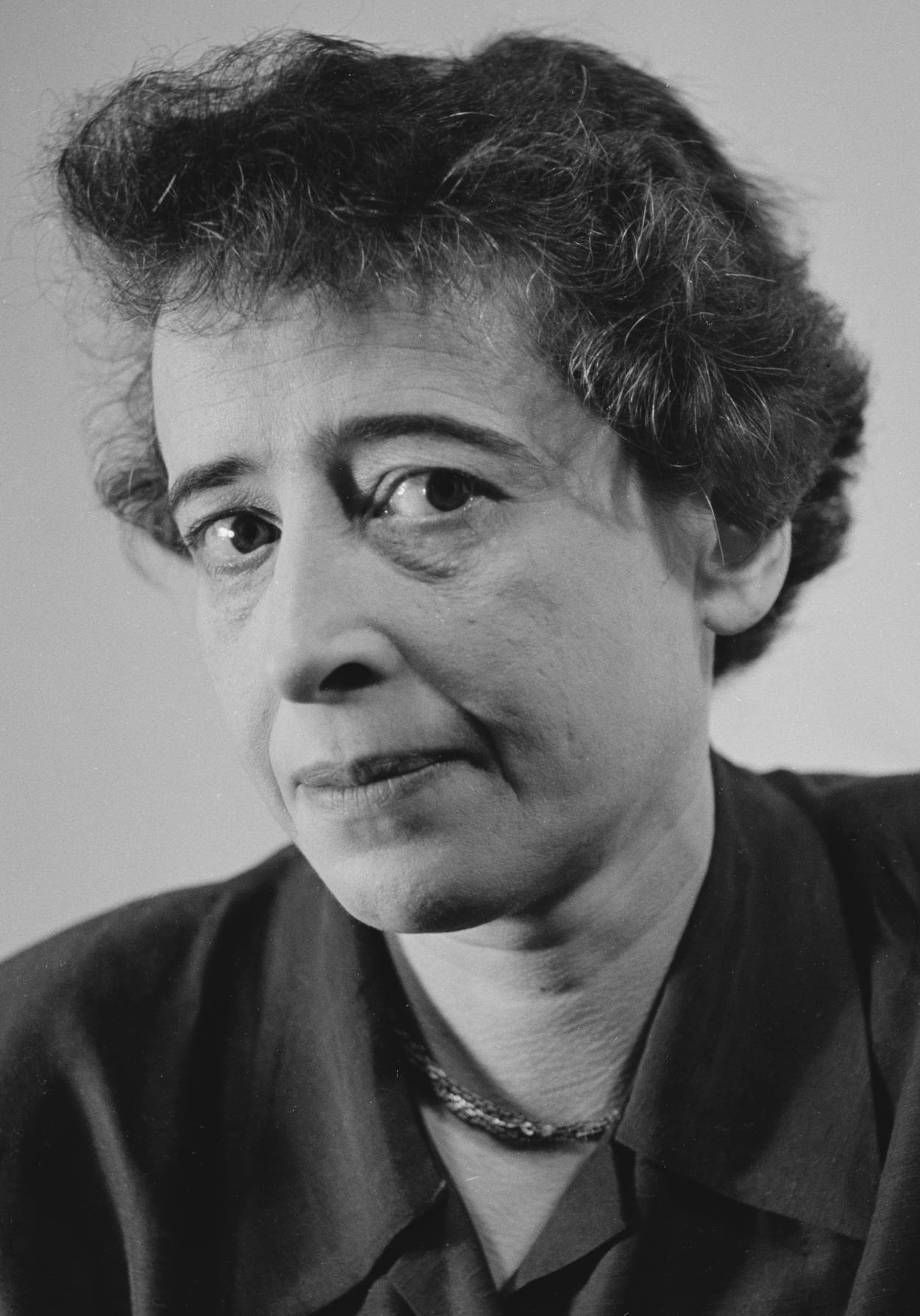

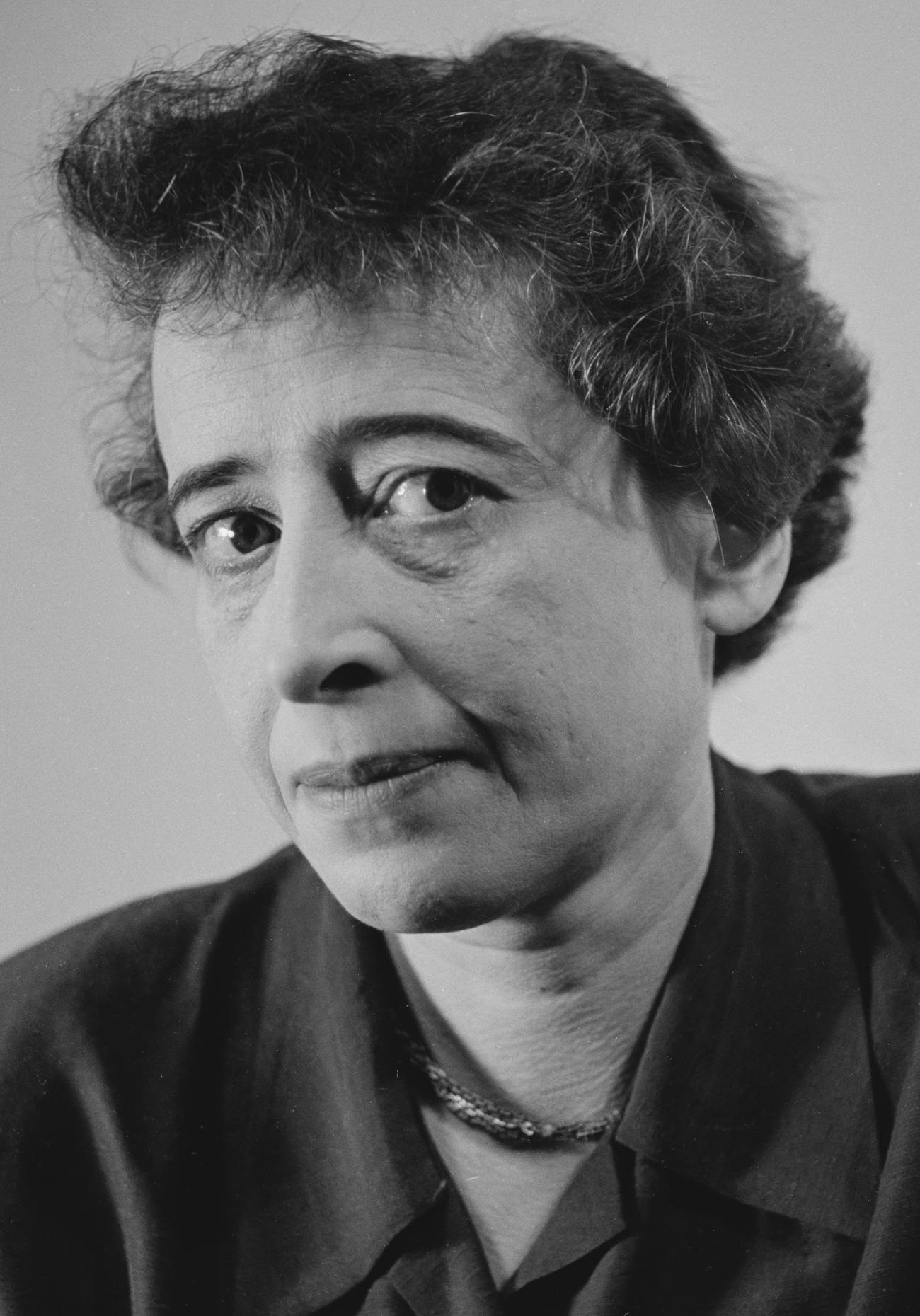

Hannah Arendt, who died 45 years ago today, is remembered as an analyst of totalitarianism and the moral failings that follow from our mental dependence on clichés. As a political theorist, she was perhaps the greatest student of Montesquieu, who argued in his 18th-century classic, The Spirit of the Laws, that absolutist government both depended on and was the consequence of the social isolation of its subjects. Like him, Arendt held that a tolerable political order can exist only where a certain kind of public sphere allows individuals to “appear” to each other, sharing ideas, criticizing the government, and collectively undertaking new kinds of action.

As a moral theorist, Arendt was perhaps the greatest student of Martin Heidegger—and, for a time, his lover. In his book Being and Time (1927), Heidegger analyzed the way that our ethical life is taken over by what he called the “They”: clichés that stifle the voice of conscience and prevent us from feeling that we are each responsible for what we do and become.

Bringing these two thinkers together, Arendt revealed how in the modern era lonely, helpless people alienated from their traditions and reliant for orientation on the moment’s reigning dogmas are unable to resist—or even notice that they are perpetrating—evil. While Nazi and Soviet totalitarianism might be the most spectacularly horrifying forms of this political and moral crisis, she argued, it also affects liberal democracies like the United States. Even apparently trivial acts of media consumption and cultural commentary, she warned, show how social isolation and irresponsibility leave us beholden to the They, ready to follow its clichés into evil deeds.

Arendt’s analysis of totalitarianism has become part of our common intellectual culture (and a source of the sort of clichés she criticized) but her proposed solutions have proved much less influential. She argued that the dangers facing our political and moral life must be met with a particular kind of mental activity she called “judgment,” and distinguished from two others: “cognition” and “thinking.”

This three-part division of mental activity remains one of the least familiar aspects of Arendt’s work. Still less familiar is a disturbing essay, “Nathalie Sarraute” (1964), in which Arendt seems to undermine hope in “judgment.” Here she gives what is perhaps her most frightening account of the power of the They in a democratic society, populated by rootless individuals seeking a false form of connectedness by consuming media and giving opinions about it. This kind of life, Arendt warns, annihilates our ability to be authentic ethical agents and thus to resist evil.

To make sense of Arendt’s theory, that what she calls “judgment” could offer a solution to our moral and political crisis—and the anguished uncertainty that her essay “Nathalie Sarraute” opens up beneath this theory’s foundations—it is necessary to review her redescription of our mental life. Arendt held that our minds perform several distinct activities, each with its own purpose—and each with its own political dimensions.

In what she called “cognition,” we deal with matters of fact and rules of logic. We use cognition to discover a truth, or to bring it to the awareness of another person. In either case, empirical facts and logical rules guarantee that there is some truth that can be known. Cognition is an instrument for achieving goals, and although it may engender temporary confusions and disagreements, it must eventually hit upon some useful information that returns us to our more or less successful activity in the world.

What Arendt calls “thinking” is quite different. This activity, which she analyzes most extensively in Thinking (1977), may begin with what seem like questions for cognition, apparently practical issues that need to be illuminated by some discoverable fact. It leads us, however, away from concern with truth, activity, and the world.

We may ask ourselves, for example, if some action we committed had been cruel. But we soon realize that the nature of cruelty is not an empirically knowable state of affairs or subject to the rules of logic. We now ask, “what does it mean to be cruel?” Such a question, Arendt argues, cannot ever arrive at a definitive answer. But the process of thinking, while it lasts, enlivens us and, if we can tolerate it, initiates an awakening that, without ever giving us certainty about the objective nature of cruelty, may help us become less cruel, because less self-assured in our everyday unreflective behavior.

Thinking and cognition each offer dangerous temptations that warp our personal lives and political choices. It may seem that cognition could be adequate to our daily needs. If we disagree about a question of fact, processes of investigation and logical reasoning assure that we can find an answer that will compel us to agree. If all our problems were of this sort, then we might well conceive of ethics and politics as the settling of practical problems, best left in the hands of experts who have mastered the cognitive skills of following rules and gathering facts.

But life is not only preoccupied with such questions. It is also, most urgently if not most frequently, concerned with questions about meaning, value, and purpose. As Arendt said in her essay “On Violence” (1970), our “scientifically minded brain trusts,” experts who would treat all questions as topics for cognition, “do not think”—and encourage us not to think either. A life without thinking lacks the vivifying challenge of posing to oneself questions like, “what does___ mean?” Worse, it is exposed to the influence of the They, and of going along with evil. Arendt argued in her analysis of the Adolf Eichmann trial that if one does not think, one can participate in a genocide as if it were nothing but a question of applying rules (doing one’s “duty” and following the law) and solving technical problems.

But while Arendt held that we must think in order to resist evil, thinking is not enough. Heidegger, whom she regarded as the greatest of modern thinkers, also participated in the evil of Nazism—precisely, she argued, as the consequence of his thinking. In “Martin Heidegger at Eighty” (1971), Arendt praised her former mentor as the reviver of thought in the modern age: “Thinking has come to life again; the cultural treasures of the past, believed to be dead, are being made to speak.” Heidegger had only not described the vacuity of thoughtless life in Being and Time; he had awakened the minds of students like the young Arendt. His seminars on Plato showed her that behind the claims and doctrines that historians of philosophy describe as Platonism, were “a set of problems of immediate and urgent relevance,” summons to thinking.

After thus exalting Heidegger, Plato and thinking, Arendt critiqued all three. Thinking abandons, as often as it can, the world of everyday life, which appears to thinkers to be the domain of prejudice and routine. Those who are able persist in thinking come to scorn what they have left behind. They imagine, as Plato expressed in his metaphor of the cave, that they have moved into a higher realm, accessible only to the few. This minority nurtures fantasies of ruling over the unthinking multitude—those still in the grip of the They—or effecting a lasting “escape from reality.” In Plato’s political writings, The Republic and The Laws, the two temptations are combined in visions of a society ruled by a class of specially trained thinkers.

Heidegger, Arendt implied, had given his support to the Nazis out of a longing to play the Platonic philosopher-king. After he realized that this wasn’t going to happen, he took flight from reality, with his later work marked by obscurantist pseudo-mysticism. Whether championing evil or choosing to ignore it, he was guilty of covering up the horrors of Nazism “with the language of the humanities.” Or as she put it in her parable, “Heidegger the Fox” (1953), he thought he had escaped the “trap” of the They, but had only trapped himself again, succumbing to the desire to influence the multitude he affected to despise and saying to himself, “‘So many are visiting me in my trap that I have become the best of all foxes.’”

Cognition and thinking can both lead to evil. Cognition leaves us trapped in the search for technical solutions, unable to notice our irresponsible conformity to the They even if it demands genocide. Thinking tempts us to despise the They and to accept the evils inflicted on other people as of little importance compared to the ideal objects of our philosophical fantasies. Both cognition and thinking risk leaving politics in the hands of elites. Cognition favors technocrats and thoughtless Eichmanns, while thinking favors Platonic utopians with schemes to transform the multitude in line with their own supposedly enlightened ideas. Neither mode of mental activity can be the basis for a well-lived life or a rightly ordered polity.

Arendt’s critiques of cognition and thinking organize her classic political writings of the 1950s and ’60s. Her attempt at a solution was slower and subtler in coming. Only toward the end of her life, in her 1970 lectures on Immanuel Kant, did she explain the political role of a third form of mental activity: judging. This way of using our minds allows us to address questions of morality and meaning that cognition eschews, while reconnecting us to other people and everyday life, from which thinking severs us. It is, she insisted, a democratic kind of mental activity, critical to the sort of public sphere that can resist totalitarian government and to the sort of personal life that can refuse the influence of the They.

Her theory of judgment is based on an apparently simple insight: “you need company to enjoy a meal.” What is it about the sense of “taste”—or any other sensory pleasures—that seems to demand we comment on what we’re tasting, share our opinion with a friend, and involve them in our experience? These pleasures, Arendt argued, possess a “basic other-directedness” or “intersubjectivity,” and inspire us to transform our unique and utterly personal physical experience into a verbal evaluation that calls for the attention of another person. “Judgment” names this process of opening our sensation into a shared, social world. Once we understand how different such moments of judgment are from cognition and thinking, Arendt held, we can see that the way we talk together about our tastes, as it happens every night around our dinner tables, is also what makes a nonauthoritarian politics possible.

This may seem absurd. Aesthetic evaluations, we might say, are so subjective and unsubstantial, that they are hardly worth our attention. Noticing the strange pleasures of our neighbor, we shrug and say that there’s no point arguing about taste. Yet, for Arendt, judgments are always, although not an argument, an appeal to the other. Consider, for example, visiting an art museum with a friend who has “good taste” in paintings. As you are walking through a gallery, not paying much attention to anything in particular as more-or-less similar works flow through your field of vision, your friend taps your arm. “Look at that!” she says, pointing to what seems to be another generic instance of some style. As the two of you move closer, she explains the care that the painter put into his use of shadow, the unusual brushstrokes in the corner, or the reference to another painter’s idiom. You begin to see what you had not seen before—that this is a beautiful painting. Your friend releases you into a new vision of the world.

Your friend has not made an argument. She did not begin by giving a logical definition of a beautiful painting and then demonstrate that the features of this painting fulfill that definition’s criteria. Nor did she make a statement about her own preferences (“I like this painting”). Your friend has drawn you into a process of interpretation, in which aspects of reality that you had been ignoring (brushstrokes, shadows, etc.) suddenly appear not as isolated material units, but as meaningful aspects of a whole.

Guided by your new insight, you see more and more elements that had previously been concealed. You are not agreeing with your friend about the painting after a process of rational deliberation, as cognition might have it. Nor are you moving away from the illusions of the everyday world into a realm of pure ideas, as thinking might. You are, rather, having more of the world, and more intensely—or rather the beauty and the brushstrokes (the meaningful whole and its parts) have you, holding you and your friend together before them.

Arendt’s account of judgment owed much to Heidegger’s theory of aesthetics. In his 1935 lecture “On the Origins of the Work of Art,” Heidegger had insisted that something like a painting cannot be understood either through technical procedures of verification (cognition) or meditations on the ideal of beauty (thinking). Instead, the painting binds us, together with others, in a special relationship, drawing us deeper into its reality. Uniting the material “earth” to the social “world,” works of art show us that it is possible to share our experiences of meaning with each other, not in a Platonic utopia separate from daily life, but here, in the present, about a specific, real phenomenon. It is in this sense that Heidegger argued that art is a “foundation” that makes it possible for a “people” to be an authentic community, one in which shared feelings and ideas are instantiated in common objects of admiration. Heidegger described this community in a vision of the members of a Greek city rallied around a “temple” in an act of worship—the sort of experience one might also have as an ardent Nazi watching Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will, a film released the same year as Heidegger’s lecture.

For Arendt, the challenge was adapting Heidegger’s insights for a better kind of politics, one founded on the exchange of multiple perspectives rather than the ecstatic experience of total agreement. She argued that a proper community is one in which individuals can gradually and consensually modify each other’s opinions about the objects of their perceptions. Judgment itself, by its very nature, recognizes that other possible judgments might exist, Arendt noted. When we express our tastes in an evaluation (“it’s delicious!”) we are not only appealing to others to share our opinion, but appealing to them to express their own. “It is this possible appeal that gives judgments their special validity,” distinct from the validity of cognition. Judgments do not confirm their truth by verifying the objective properties of the object of judgment (we won’t settle our disagreement about the painting’s merits by measuring its dimensions). Nor are they, as in Heidegger’s analysis, unanimously enraptured by submission to the collective. Rather, for Arendt, judgments “‘woo’ and ‘court’ the agreement of everyone else,” in a manner “which takes all others and their feelings into account.”

My judgment is “true,” therefore, to the extent that it reaches into other people’s perspectives, sees as they see, convinces them to see as I see, and thus brings us all together into an expanded vision. It is a kind of generalized seduction, in which, using impassioned rhetoric (“look at those marvelous brushstrokes!”), one draws one’s fellows into agreement not only with the beauty of the object beheld, but also the beauty of the speech through which the object’s beauty reveals itself. This, Arendt concluded, is the structure of the democratic public sphere: a space in which rhetorical appeals to a diverse audience reach toward consensus, while training citizens in the arts of giving and changing their opinions.

Arendt’s theory of judgment, and her sense that it could be the basis for politics, where cognition and thinking fail, is vulnerable to a number of objections. Although she is popularly known as a critic of political deceit, Arendt argued that the idea of “truth” is out of place in a politics based on judgment. In trying to “seduce” each other, we use stirring language, not the factual and logical claims of cognition, or the attempts to arrive at clear concepts characteristic of thinking. Those who criticize our own era as a time of “post-truth,” or are troubled by the presence of rhetoric and emotion in politics, may fear Arendt’s theory legitimates populist demagogues.

But the most powerful critique of her theory was suggested by Arendt herself in her 1964 essay on Nathalie Sarraute. Born Natalia Tcherniak, Sarraute (1900-1999) emigrated to France with her Russian Jewish family at the age of 2. She was one of the most original novelists of modern French literature, and the subject of Arendt’s essay, Sarraute’s 1963 novel The Golden Fruits (Les Fruits d’Or), is her masterpiece. Sarraute developed an innovative style which, instead of dialogue, presents readers elaborately metaphorical descriptions or monologues revealing what characters really think as they speak to each other. In the silent darkness from which apparently benign remarks emerge writhe tangled, nasty motives.

A ubiquitous and totalizing media conversation has made it impossible to speak one’s mind because no one thus exposed to the din of so many voices and anxious to join them, can have a mind of their own to speak.

Sarraute drew out the vicious pettiness behind the superficialities of everyday conversation. In The Golden Fruits, she satirized the literary establishment, showing how judgments about the merits of a book—in this case a fictional novel also titled The Golden Fruits—are about anything but the book itself. Over the course of the story, the fictional novel’s reputation rises, becoming an obligatory topic of praise, and then falls, becoming a nearly universal object of derision. But no one ever cites a line of it, or has an authentic opinion—each character frantically tries to score points with the others by expressing a clever variation on the dominant mood.

Arendt found The Golden Fruits “exquisitely funny” in its attacks on “the milieu of the presumably ‘inner-directed’ elite of ‘good taste’ ... intellectuals boasting of the highest standards.” Such people, who imagine themselves as being the best equipped to make aesthetic judgments, are in fact beholden to clichés. But Arendt did not seem to notice that the characters in The Golden Fruits seem to be good Arendtians, exchanging their judgments in democratic fashion. “They exhaust all aspects, all arguments and outdo each other,” using their rhetorical skills to try to seduce each other into new perspectives. But all this talk is only a frantic effort to escape the “hell” of isolation in a modern liberal society, no less profound than the isolation of a totalitarian regime.

“‘They’ are all alike,” Arendt said of Sarraute’s characters, because, yearning for human connection, they try to use their superficially insightful twists on the ruling opinion as “passwords and talismans” that grant them entry into some select club of “those who belong together.” They cannot share personal experiences of the book with others, because their experiences have been impersonal from the outset, warped by their anxious desire to generate statements about it that will signal both their loyalty to the fashion of the moment and their individual brilliance. A ubiquitous and totalizing media conversation has made it impossible to speak one’s mind because no one thus exposed to the din of so many voices and anxious to join them, can have a mind of their own to speak.

In “Nathalie Sarraute,” it appears that judgment, too, is powerless against the They. Instead of going along with the They unconsciously, or scorning it, as we might in cognition and thinking, in judgment we try to anticipate the They, to express an opinion that will so adeptly tweak the canons of acceptable commentary that the They grants us a fleeting sense of group membership and personal worth. Sixty years after Arendt’s essay, as social media have brought these processes of judgment into the deepest intimacies of what was once private life, it seems ever less possible that people whose minds have been trained by such exercises of giving “passwords” in order to “belong”—and we are all such people now—could free themselves from the They.

We can see—as Geoff Shullenberger, drawing on the work of René Girard, has recently argued in Tablet—this process at work today on social media. Users of Twitter, Shullenberger argues, express opinions in order to gain points in the form of likes, comments, etc.—symbols that we are part of the They, held in the approving gaze of an imaginary collectivity. From Shullenberger’s Girardian perspective, these acts of judgment are motivated from the outset by a “mimetic” desire, that is, a longing to have what others seem to want (likes, followers, a fuller participation in the discourse). When we give an opinion on Twitter, we are not inspired by an authentic, personal desire to have our particular relationship to the world enlarged by an encounter with other such relationships, but by a derivative, imitative desire to have the attention that other people seem to enjoy.

This situation is, in a sense, even worse than thoughtless conformity with the They, since we are actively competing to give new variations on the reigning clichés. We experience this generalized competition for attention as a “steady grind of envy, resentment and reciprocal hostility,” which, Shullenberger warns, is periodically relieved as we “redirect ... aggression to a ‘surrogate victim,’” what Girard called a “scapegoat.” Like the characters of Sarraute’s The Golden Fruits, we may laud a hero of the moment, or “sacrifice” a victim, without ever being troubled by the least complaint of conscience.

Arendt concluded her essay with a note of false optimism. She claimed that The Golden Fruits ends with a scene in which “Nathalie Sarraute turns from the ‘they’ and the ‘I’ to the old We of author and reader. It is the reader who speaks: ‘We are so frail and they so strong. Or perhaps ... we, you and I, are the stronger, even now.” Arendt deceived herself or her readers. The scene she described sees a deranged fan of the novel writing to its author, who has fallen into obscurity. The fan moans, in a language full of pitiful clichés, that the literary crowd was wrong to turn away from The Golden Fruits and praises herself for her “resistance.” But this is only another appeal to the They, nursing the hope that public opinion will turn again to recognize the author’s brilliance, and her own.

That Arendt missed the point, reading this moment as an affirmation of the possibility of authentic relating to an author, is an ironic defeat for her theory. She hoped to build a democratic politics from the kind of connections readers make to books and to each other, but, as she tried to ground this hope in her own experience of literature, she misrepresented Sarraute’s bleak vision. Arendt’s hopes for a solution to our moral and political crisis through “judgment” are menaced by our longing to escape anxious loneliness through communion in idle chatter, the self-aggrandizing histrionics of “resistance,” and, perhaps most troubling, the temptation—felt even by minds such as Arendt’s—to conceal our plight with hopeful clichés.

The great moral and political insight of Arendt’s work is that there is only a short step from the apparently trivial problem of having inauthentic opinions to the horrors of mass violence. But none of the modes of mental activity she identified—cognition, thinking, and judgment—seem adequate to deliver us from the conscience-benumbing power of the They. As social media extend the sort of cultural commentary satirized in The Golden Fruits from a small circle of literati to the entire world, it is vital that we consider Arendt’s errors as well as her insights, and ask how (or whether) we could protect our lives from irresponsibility and inauthenticity, and our politics from violence and persecution.

Blake Smith, a contributing writer at Tablet, lives in Chicago.