When Anne Frank began keeping a diary in 1942, documenting her life in the secret annex in Amsterdam, she assumed that no one would ever want to read it. “It seems to me that later on neither I nor anyone else will be interested in the musings of a thirteen-year-old schoolgirl,” she wrote. Even so, she instinctively approached her writing the way a “real writer” does, as a kind of performance. The diary entries are framed as letters to an imaginary correspondent, “Kitty,” a device that allowed Anne to experiment with writing for an audience. And while she uses real names for herself and her family, the other residents of the annex are given pseudonyms: the van Pels family became the van Daans and Fritz Pfeffer was called Albert Dussel, a way of turning them into Anne’s own creations, characters in her story.

It might seem that eight ordinary people trapped in an attic would offer little scope for storytelling; but in fact the diary is full of dramatic episodes, carefully staged and narrated by Anne. “You may wonder if there’s ever a day that passes without some kind of excitement,” she writes on July 26, 1943. That day’s excitement was truly momentous—an air raid on Amsterdam, followed by news of Mussolini’s resignation as leader of Italy—but Anne is equally fascinated by the miniature human dramas taking place in the Annex itself.

Three days later, for instance, there is a sketch of a debate between Anne and Dussel over the merits of a book that he recommended and she disliked. She records their dialogue, with censorious contributions by Mrs. van Daan, as a comedy that turns furious: “I could have slapped them both for poking fun at me. I was beside myself with rage,” she notes. Her anger, however, only sharpens her perceptions, and she gives the impression of seeing straight through all the people around her: Mrs. van Daan’s vanity, Dussel’s pomposity, her own mother’s coldness.

Anne’s ability to write without embarrassment, to say exactly what she thought, felt, and meant, is a literary achievement that reflects an unusual strength of character. “I face life with an extraordinary amount of courage,” she wrote in June 1944, after nearly two full years of house arrest, fearing discovery and death at every waking moment. “I feel so strong and capable of bearing burdens, so young and free! When I first realized this, I was glad, because it means I can more easily withstand the blows life has in store.”

It is this tone of hopeful resolve that accounts, more than anything else, for the appeal of Anne Frank’s diary. It might seem strange that a book by a girl who was essentially imprisoned for two years, before dying a horrible death at the age of 15, should be read, in the words of the American paperback’s cover, as “a timeless testament to the human spirit.” And the truth is that the diary contains many expressions of fear and despair, exactly as one would expect from someone in Anne’s situation. “I’ve been taking valerian every day to fight the anxiety and depression, but it doesn’t stop me from being even more miserable the next day,” she wrote on Sept. 16, 1943, after more than a year in hiding. “A good hearty laugh would help more than ten valerian drops, but we’ve almost forgotten how to laugh.”

Yet it is not the moments of demoralization and despair that readers of Anne Frank’s diary tend to remember. Rather, it is the sense the diary gives of youth and life having their way despite every obstacle. “I’m young and strong and living through a big adventure,” she wrote on May 3, 1944. This determination to remain positive extends to Anne’s assessment of humanity at large—at least, some of the time. “Later on we’ll no doubt be astonished at how many good people in Holland were willing to take Jews and Christians, with or without money, into their homes,” she writes; and indeed, the four Dutch Christians who helped to save the Jews in the Annex presented her with daily examples of extraordinary goodness.

Perhaps the most widely quoted line in the diary comes from her entry of July 15, 1944: “I still believe, in spite of everything, that people are truly good at heart.” Read in context, however, Anne’s avowal sounds almost desperate, something she says not because it’s true but because she needs to believe it: “It’s utterly impossible for me to build my life on a foundation of chaos, suffering and death,” she continues. And she was fully aware of what human beings were proving themselves capable of. In February 1944, she described the inhabitants of the Annex discussing matter-of-factly how “millions of peace-loving citizens in Poland and Russia have been murdered and gassed.”

Is there something evasive about describing those victims of the Holocaust simply as “citizens,” rather than as Jews? Certainly, whenever she is writing about the plight of the Jews, Anne’s language tends to become impersonally sententious. “If, after all this suffering, there are still Jews left in the world, the Jewish people will be held up as an example. ... There will be a way out. God has never deserted our people.” Perhaps this was an echo of the way such matters were discussed in the Annex. But it also registers Anne’s sense that she had the responsibility to be what she indeed became—a quasi-official Jewish spokesperson, tasked with demonstrating the innocence and humanity of the Jews to the world at large.

This insistence that Jews are just people, no different from anyone else, is another reason Anne Frank’s diary has been the most universally acceptable work of Holocaust literature. For Anne, Jewishness is a purely arbitrary label: it defines the way people treat her, but it has nothing to do with her actual thoughts or experiences. “I sometimes wonder if anyone will ever ... not worry about whether or not I’m Jewish and merely see me as a teenager badly in need of some good plain fun,” she writes. Coming from her, it sounds so self-evident and modest a wish that it is amazing it could have been denied for so long. For readers of her diary, empathizing with Anne Frank has been a way of symbolically granting this Jewish claim to full humanity—but only when it was too late to make a difference.

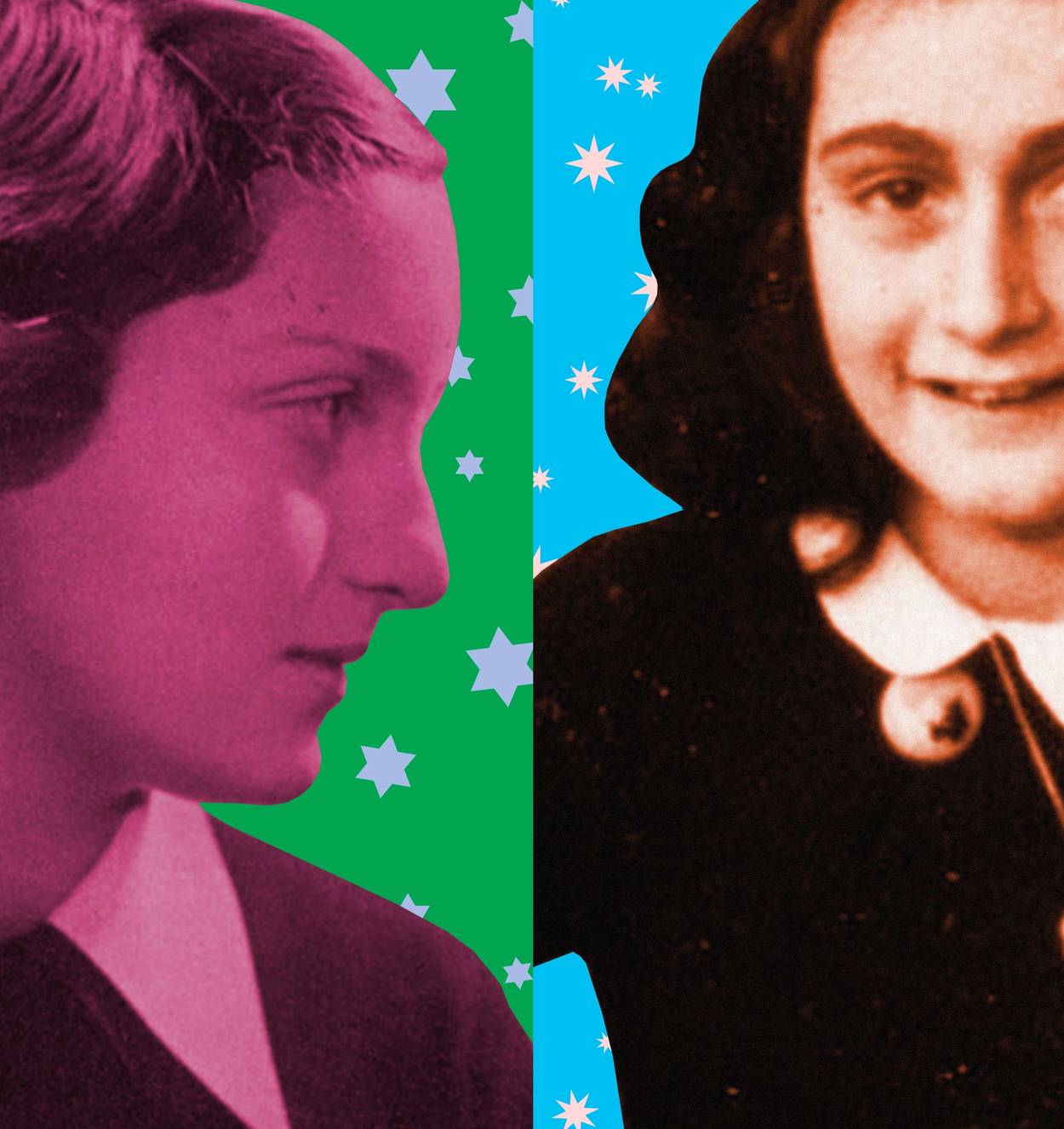

While Anne Frank was writing in Amsterdam, another young Jewish woman was keeping a very different kind of diary in the future state of Israel. Hannah Senesh was 18 years old when she made her way from Budapest to Palestine in September 1939, just as World War II was beginning. She had been selected by the Women’s International Zionist Organization to receive one of the handful of entry permits issued by the British, since she was just the kind of immigrant the Yishuv wanted: young, ideologically committed, and willing to undertake hard physical labor.

Her destination was Nahalal, an agricultural school where she would be trained in the techniques of running a farm. Senesh would spend two years there, followed by two years at Sdot Yam, a kibbutz on the Mediterranean coast near Haifa. This was the process by which ordinary European Jews became pioneers of a new country, and many of those who went through it went on to form Israel’s social and political elite. In 1941, Senesh wondered in her diary whether that would be her fate: “I wonder whether I wasn’t really meant to lend a helping hand in government? I’ve noticed at times that I have the ability to influence people, to comfort and reassure them, or to inspire them.”

She would become an inspiration to the Jewish state, but not in the way she imagined. In 1943, Senesh volunteered to join a commando unit of Jewish soldiers that was being formed under the aegis of the British army to parachute into Nazi-occupied Yugoslavia—the only woman among the 37 soldiers. To the British, the unit’s mission was to rescue downed RAF pilots and help to organize partisan resistance; to Senesh herself, the primary goal was to make it to Hungary, home to a million Jews—including her mother—whose lives were imperiled after the Germans occupied the country in March 1944. Soon after crossing the Hungarian border, however, Senesh was captured, imprisoned, and tortured. She was executed by firing squad on Nov. 7, 1944, when she was 23 years old.

Senesh only spent about four years in Palestine, from late 1939 to early 1944, and she was on the periphery of events there. But her diary offers an important record of this critical period in Israel’s prehistory. The personal and ideological transformations that she underwent in that time make her representative of a whole generation of Zionists—thousands of young men and women who were seized with an irresistible impulse to leave their homes and families and try to build a new society.

Like Anne Frank, Senesh began keeping her diary when she was 13 years old. She lived in Budapest with her mother and brother in an assimilated, middle-class family; her father, a writer of some renown, had died when she was eight. From the beginning of the diary, Senesh had the feeling that she was not cut out for an ordinary life.“I would rather be an unusual person than just average,” she wrote in August 1936, not long after her 15th birthday. “When I think of an above-average man I don’t necessarily think of a famous man, but of a great soul … a great human being. And I would like to be a great soul. If God will permit.” She hoped to follow in her father’s footsteps and become a writer.

But while her diary and poems would indeed become famous, Senesh was not a natural storyteller. With Anne Frank, the reader has the sense that if she had lived she would certainly have become a writer of importance, even if the diary itself never saw the light of day. With Hannah Senesh, it is primarily the history she lived through that ensures her claim on posterity. This difference mirrors the one between Anne’s universalism, which appeals to readers of every background, and Senesh’s committed Zionism, which makes her a specifically Jewish heroine.

Exactly what made Hannah Senesh become a Zionist is a question the diary doesn’t really answer; she appears to have embraced the cause virtually overnight. In the earlier part of the diary, she seldom writes about Jewishness and has no real interest in Jewish observance, something that remained true until the end of her life: “The trouble with the synagogue is that I don’t find it at all important, and I don’t feel it to be a spiritual necessity; I can pray equally well at home,” she writes in 1936. But she was early made aware that Jewishness set her apart in Hungarian society. In one small but telling episode, Senesh was elected to an office in her school’s literary club, only to see the election annulled because positions weren’t open to Jews. “Only now am I beginning to see what it really means to be a Jew in a Christian society,” she writes in June 1937, shortly before her 16th birthday. “But I don’t mind at all. It is because we have to struggle, because it is more difficult for us to reach our goal that we develop outstanding qualities.”

It was in March 1938, when Nazi Germany annexed Hungary’s neighbor Austria, that Senesh was struck for the first time by the real danger facing Europe’s Jews. “We’re so thoroughly prepared for the worst and feel it’s really only a matter of time,” she writes in July. It is against this background of tension, fear, and hopelessness that Senesh writes, almost offhandedly, about her conversion to Zionism. “I don’t know whether I’ve already mentioned that I’ve become a Zionist,” begins the diary entry for Oct. 27, 1938. “The word stands for a tremendous number of things. To me it means, in short, that I now consciously and strongly feel that I am a Jew, and am proud of it.”

But Senesh was unusual even among Zionists in her conviction that she must immediately emigrate. “My primary aim is to go to Palestine,” she writes, and though she doesn’t discuss her motivations in any depth, it is easy to see how, for a young woman facing an uncertain future both personally and politically, this concrete goal served as a source of purpose and direction. “I am immeasurably happy that I’ve found this ideal, that I now feel firm ground under my feet and can see a definite goal toward which it is really worth striving,” she writes.

Remarkably, even as Europe moved toward war, Senesh managed to make her plans a reality: less than a year after this diary entry, she was in Palestine. Her life there was outwardly undramatic: she did nothing but go to school, learn Hebrew and farming, and engage in tedious labor. The interest of the diary lies, rather, in Senesh’s continual struggle with doubts over whether immigrating had been the right decision. From the outside, her story looked like a Zionist fable with a happy ending: a Jew flees a continent on the brink of Holocaust and finds a new life in the Jewish homeland.

But two questions haunted her, both of which carried wider implications for the Zionist project. First, Senesh wondered whether she had done right to save herself while leaving her mother to face the war alone. Zionism was meant to be the redemption of the whole Jewish people, but it had turned out to be the work of an ideological vanguard, which now found itself cut off from the vast majority of Jews left behind in Europe. “I can think of nothing now but my mother and brother,” she writes in January 1943. “I am sometimes overwhelmed by dreadful fears. Will we ever meet again? And one question keeps torturing and tormenting me: Was what I did intolerable? Was it unmitigated selfishness?” In another entry, she writes, “I feel a need to recite the Yom Kippur confession: I have sinned, I have robbed, I have lied, I have offended—all these sins combined, and all against one person,” her mother.

The other doubt in Senesh’s diary, which keeps coming back despite her earnest efforts to suppress it, has to do with her own hopes for the future. Having grown up in a bourgeois intellectual family, she was now living the life of a manual laborer: “Today I washed a hundred and fifty pairs of socks,” she writes in February 1942. “I thought I’d go mad. No, that’s not really true. I didn’t think of anything.”

Did serving the Zionist cause and the Jewish people require the complete sacrifice of any hope for individual achievement, for personal satisfaction? Senesh often feared that it did. At the Nahalal agricultural school, she writes in April 1940, she learned about “root cells, which are the first to penetrate into the earth and prepare the way for the entire root. Meanwhile, they die. My teacher used the comparison: these cells are the pioneers of the plants.” The comparison “flew over the heads of the other pupils,” she writes, but she saw its implications for herself: “Shall our generation become such root cells, too?”

Seen against this psychological background, it becomes easier to understand Senesh’s decision, in 1943, to volunteer for the mission that would end in her death. As a novice Zionist back in Hungary in 1938, she had enjoyed a sense of certainty and purpose that she lost amid the compromised reality of life in Palestine. Becoming a soldier would give her back that meaning. It would liberate her from washing socks and assign her a crucial role in the Zionist struggle; and it would allow her to feel that she was doing something to help the Jews left behind, including her mother.

No wonder that as soon as she heard about the planned mission, in February 1943, she felt called to enlist: “I see the hand of destiny in this just as I did at the time of my aliyah,” she wrote in her diary. “I wasn’t master of my fate then, either. I was enthralled by one idea and it gave me no rest. … Now I again sense the excitement of something important and vital ahead, and the feeling of inevitability connected with a decisive and urgent step.” That September, in the middle of army training, Senesh confirmed that despite all her doubts and fears, she believed her life had unfolded exactly as it was supposed to: “In my life’s chain of events nothing was accidental. Everything happened according to an inner need.”

One of Senesh’s fellow soldiers recalled that on the day she set off for Hungary, she pressed into his hand a Hebrew poem she had written, “Blessed Is the Match.” Just four lines long, it offers a metaphor for the sacrifice she was about to undertake: ”Blessed is the match consumed in kindling flame,” it begins and ends. In fact, Senesh’s death did not ignite any flame in Nazi-occupied Hungary. In the most concrete sense she gave her life for nothing, and it’s possible to view the entire mission as a mere gesture, an attempt to expiate the shame that the Yishuv felt over its helplessness to stop the Holocaust.

But in a longer perspective, Senesh’s death achieved the same thing as the similarly hopeless rebellion mounted by the Jews of the Warsaw Ghetto in 1943, whose leader Mordecai Anielewicz wrote in his last letter: “The dream of my life has risen to become fact ... Jewish armed resistance and revenge are facts “ Senesh, too, gave her life to prove Jews did not have to await their fate, that they could take up arms against their enemies—a cardinal principle of Zionism, and one that Israelis would have to rely on again and again.