The True Story of the German Jew Who Tracked Down the Kommandant of Auschwitz

In an excerpt from Thomas Harding’s thrilling ‘Hanns and Rudolf,’ Rudolf Höss is taken prisoner, and beaten

It is May 1945. In the aftermath of the Word War II, the first British War Crimes Investigation Team is assembled to hunt down the senior Nazi officials responsible for the greatest atrocities the world has ever seen. One of the lead investigators is Lieutenant Hanns Alexander, a German Jew who is now serving in the British Army. Rudolf Höss is his most elusive target.

As Kommandant of Auschwitz, Höss not only oversaw the murder of more than one million men, women, and children; he was the man who perfected Hitler’s program of mass extermination.

Höss has fled Berlin and is hiding in a barn near the Danish border. He is the one man whose testimony can ensure justice at Nuremberg. Höss wants to escape to South America before the investigator can catch up with him. Following a bruising interrogation of Höss’ wife, Hedwig, Hanns Alexander has discovered the Kommandant’s identity and where he is hiding.

The chase is on.

***

Gottrupel, Germany, 1946. As soon as Hanns had heard Hedwig Höss’s confession, he rushed over to Captain Cross, and the two quickly agreed on a plan. They should carry out the arrest under the cover of darkness, and as soon as possible. And they would need serious firepower. It was unclear if Rudolf was alone, and there was every chance that he would resist arrest.

Over the next hour the men of Field Security Section 92 were assembled and briefed on the operation. Many of them were German Jews like Hanns, from the Pioneer Corps—men who had been driven out of their country and who had lost family members in Auschwitz. Some had kept their original names, such as Kuditsch and Wiener. Others had taken on British-sounding names, like Roberts, Cresswell and Shiffers. There were also English-born soldiers from Jewish families, similarly enraged, men such as Bernard Clarke, from the south coast, and Karl “Blitz” Abrahams, from Liverpool.

Rifles were checked and supplies loaded into the trucks: blankets, a field radio, cartons of extra ammunition. A box of axe handles was stashed into the back of one of the vehicles. Hanns, meanwhile, put a call in to the commander of Field Security Section 318, explaining the mission and requesting additional backup. He also arranged for a doctor from the 5th Royal Horse Artillery regiment to join them.

Two hours later, the small convoy of trucks and jeeps hurried along the narrow roads towards Gottrupel. Darkness had descended on the German countryside. Inside the vehicles twenty-five men sat nervously on benches, fidgeting with their gear. Hanns knew that they all wanted to be “in on the kill.”

It was pitch black and utterly quiet when the convoy rolled into the farmyard in Gottrupel at eleven o’clock on March 11, 1946. Getting out of his jeep, and accompanied by the medical officer and the driver, Hanns ordered the others to hold back. He walked towards the barn and knocked loudly.

Rudolf was “woken with a start” by the commotion outside. At first, he was unconcerned, assuming “that it was one of the robberies which were very frequent at this time in the area.” Then he heard a stern voice ordering him to open up. Realizing that he had no alter- native, Rudolf opened the door. Two men in British uniform stood facing him. Rudolf could tell by their insignia that one was a captain, the other a doctor. Behind them stood at least twenty soldiers, their guns drawn. He was confused by the lights and the presence of all these men.

Without warning the tall, handsome, fierce-looking captain thrust a pistol in his mouth. He was then searched for cyanide pills. “Go and see that he is clean,” Hanns said to the doctor, holding Rudolf while his mouth was searched for vials of poison. After a few seconds the doctor gave the all-clear.

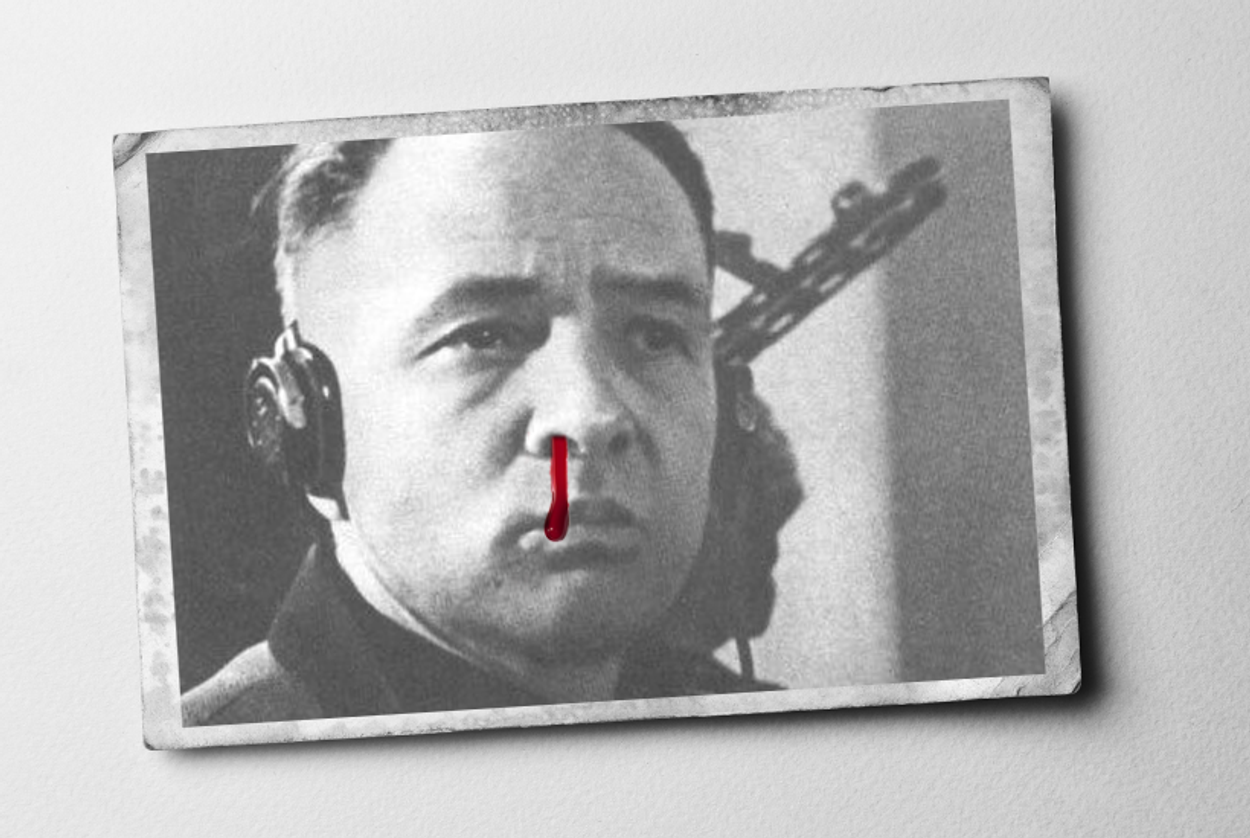

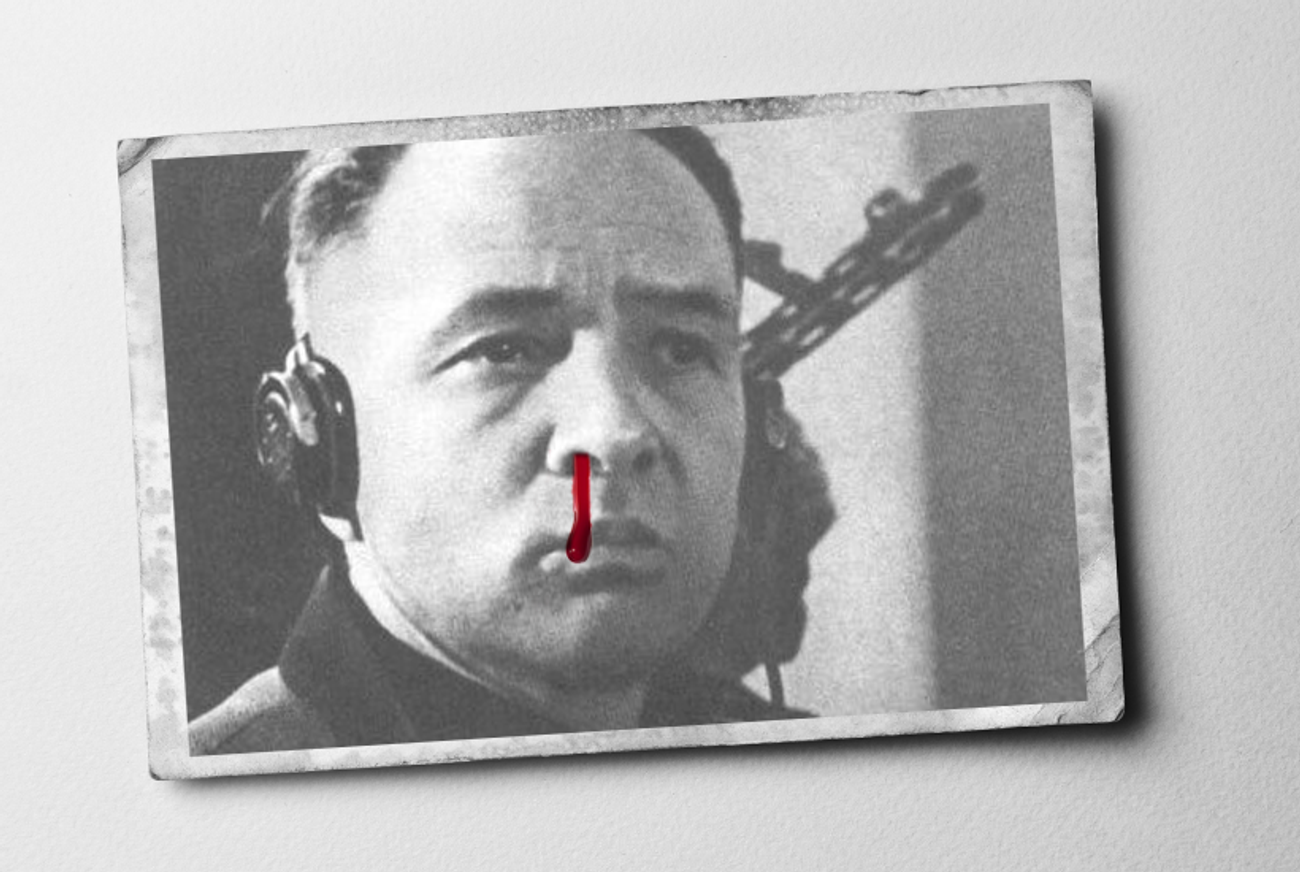

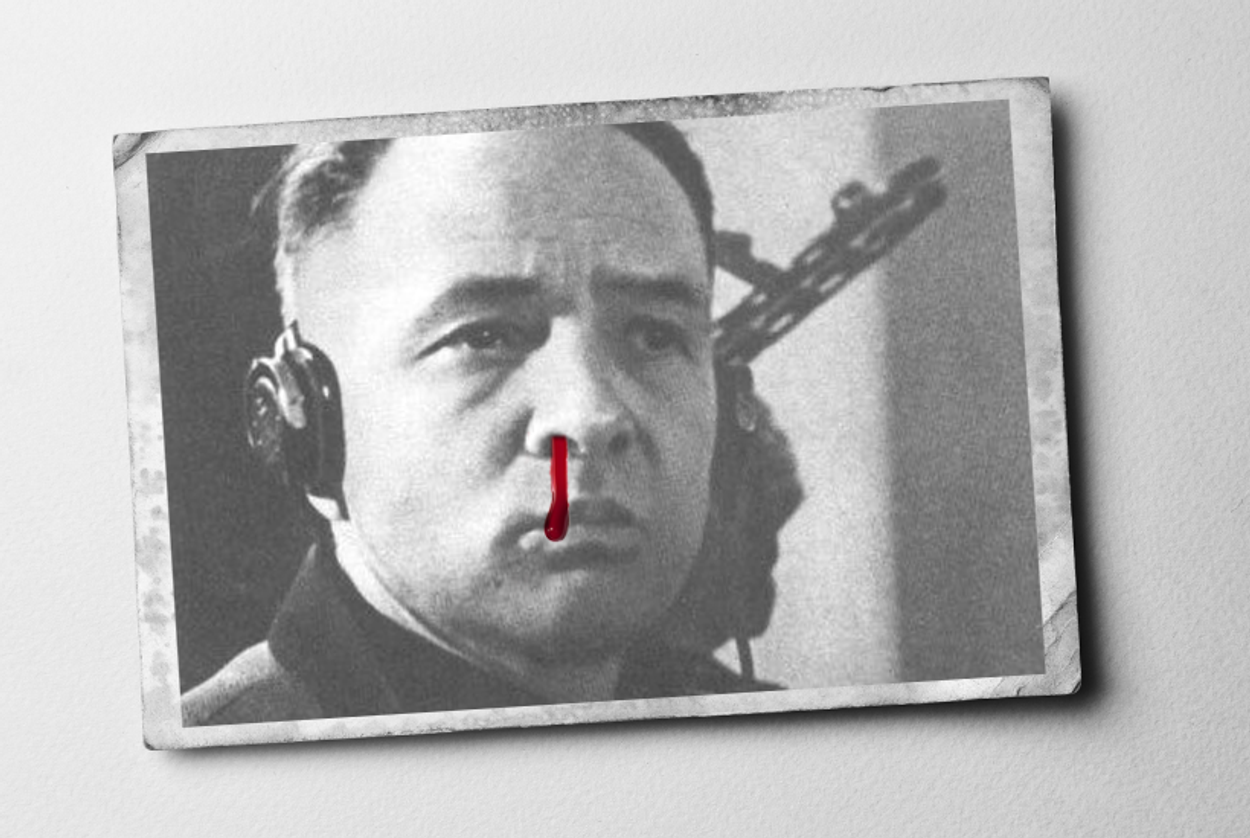

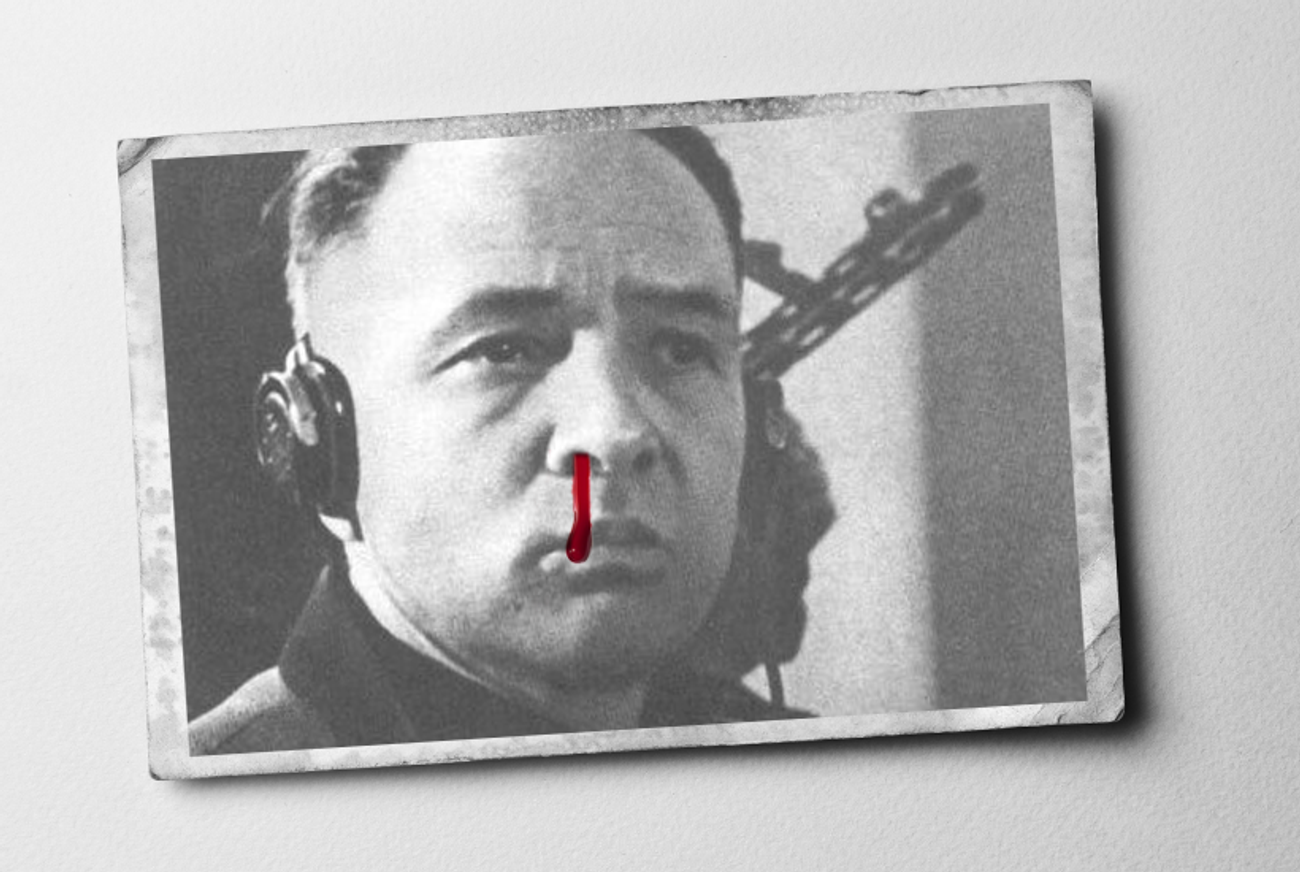

The captain began talking in perfect German. It was immediately obvious to Rudolf that the man was a native speaker. He introduced himself as Captain Alexander of the British War Crimes Investigation Team, and demanded to see Rudolf ’s papers. The Kommandant handed over his identity documents—Franz Lang, temporary card number B22595. Hanns had seen this name on the plate next to the barn door, but knew it to be untrue. The man looked too similar to the figure in the photograph that he carried with him. Older, sicker, thinner, to be sure, but similar.

Hanns flashed the photograph and told Rudolf that he believed him to be the Kommandant of Auschwitz. Again Rudolf denied the claim, pointing once more at his identity papers. Perhaps he would be able to wriggle out of this: after all, the British had let him slip through their fingers in the past.

However, Hanns remained convinced. He rolled back the man’s shirtsleeves to see if there was a blood group tattooed on his arm, but there was nothing. The conversation went around in circles. Yet Hanns wasn’t going to give up. His eyes roved about the barn entrance searching for a way to prove the man’s identity.

At last Hanns looked down and noticed his wedding ring. “Give it to me,” he said.

“I can’t, it has been stuck for years,” Rudolf answered. “No problem,” Hanns said, “I’ll just cut off your finger.”

Hanns asked one of the members of Field Security Section 92 to fetch a kitchen knife from inside the barn. When this man returned, he handed the knife to Hanns, who stepped forward, clearly intent on carrying out his threat. Realizing he would lose the ring either way, Rudolf reluctantly removed the wedding band from his finger. Then, staring furiously at Hanns, he handed it over. Hanns held the ring up to the light and looked inside the band, where he saw the names “Rudolf ” and “Hedwig” inscribed. Hanns thanked him and put the ring in his pocket.

Having identified his man, Hanns was ready to make the arrest. But he sensed that his colleagues wanted to vent their hatred. Indeed, he wanted to join in. He had to make a quick decision: should he allow them free rein, or should he protect Rudolf ? Turning to his men, Hanns said, “In ten minutes I want to have Höss in my car—undamaged” and walked off. He knew that this made him responsible for what was about to happen, but he was prepared to face the consequences.

Rudolf was immediately surrounded by the remaining soldiers, who dragged him to one of the barn’s slaughter tables, tore the pajamas from his body and beat him with axe handles. Rudolf screamed, but the blows kept coming. After a short period, the doctor spoke to Hanns: “Call them off,” he said, “unless you want to take back a corpse.”

Just as suddenly as it had started, the beating stopped. A rough woolen blanket was wrapped around Rudolf’s shoulders, and he was carried out of the barn.

***

At around midnight the prisoner was loaded into the truck. Hanns and three sergeants climbed in after. Hanns told the driver to make for Heide, where they would deliver Rudolf to the local jail. Hanns sat on one of the benches next to Rudolf in the back of the truck. As the vehicle rumbled along the narrow roads, Hanns asked the prisoner a series of questions: What is your name? What was your rank in the SS? What role did you play during the war? Did you work at Auschwitz? At last, after repeated questioning, Rudolf confirmed to Hanns that he had worked as the Kommandant of Auschwitz, and that he had been “personally responsible for the deaths of 10,000 people.” Hanns realized with rising excitement that not only had he captured his man, but he was willing to talk.

When they arrived in Heide two hours later, the trucks pulled up at a bar in the center of town, where Paul was waiting for them. With Rudolf left in the truck, under guard, Hanns and the other men, around twenty-five in all, piled into the bar. Extraordinarily, Hanns had interrupted the safe delivery of the most wanted war criminal into custody, in order to celebrate.

Paul described this scene to his parents in a letter he penned the next day:

13 March 1946

Hanns had a very successful time here, though very busy. But he is not leaving empty handed. He caught the bastard from Auschwitz. I have never seen such a shit in all my life. After all was over I found the party for celebration while Rudolf ’s feet got cold in the car under escort. We drank to the success with champagne and whiskey. Just right for the job. But will have to leave the details of the description to Hanns. He is a good bloke but don’t tell him otherwise he gets eingebildet [smug].

After they were finished celebrating, Hanns walked back to the truck, pulled Rudolf out of the vehicle, removed the blanket from his shoulders, and made him walk naked to the prison on the other side of the snow-covered main square. Once inside the prison Hanns, along with a sergeant from the Field Security Section, began Rudolf ’s first formal interrogation. Alcohol was forced down the prisoner’s throat and they beat him with his own whip, confiscated from the barn in Gottrupel. A pair of handcuffs were on his wrists at all times, and with the temperature in the cell well below freezing, Rudolf ’s uncovered feet quickly developed frostbite.

***

Three days later, on March 15, 1946, Hanns delivered Rudolf to Camp Tomato, a British-run prison near the town of Minden. There, Colonel Gerald Draper—the War Crimes Group’s lawyer—began a further round of intensive questioning. A few hours afterwards, Rudolf’s statement was typed up into an eight-page confession and a one-paragraph summary. It was the first time that a concentration camp Kommandant had provided details of the Final Solution. Rudolf had confessed to coordinating the killing of two million people.

***

From Hanns and Rudolf: The True Story of the German Jew Who Tracked Down and Caught the Kommandant of Auschwitz, by Thomas Harding. Copyright © 2013 by Cackler Harding Ltd. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Thomas Harding is a journalist who has written for the Financial Times, Sunday Times, and The Guardian, among other publications. He lives in Hampshire, England.

Thomas Harding is a journalist who has written for the Financial Times, Sunday Times, and The Guardian, among other publications. He lives in Hampshire, England.