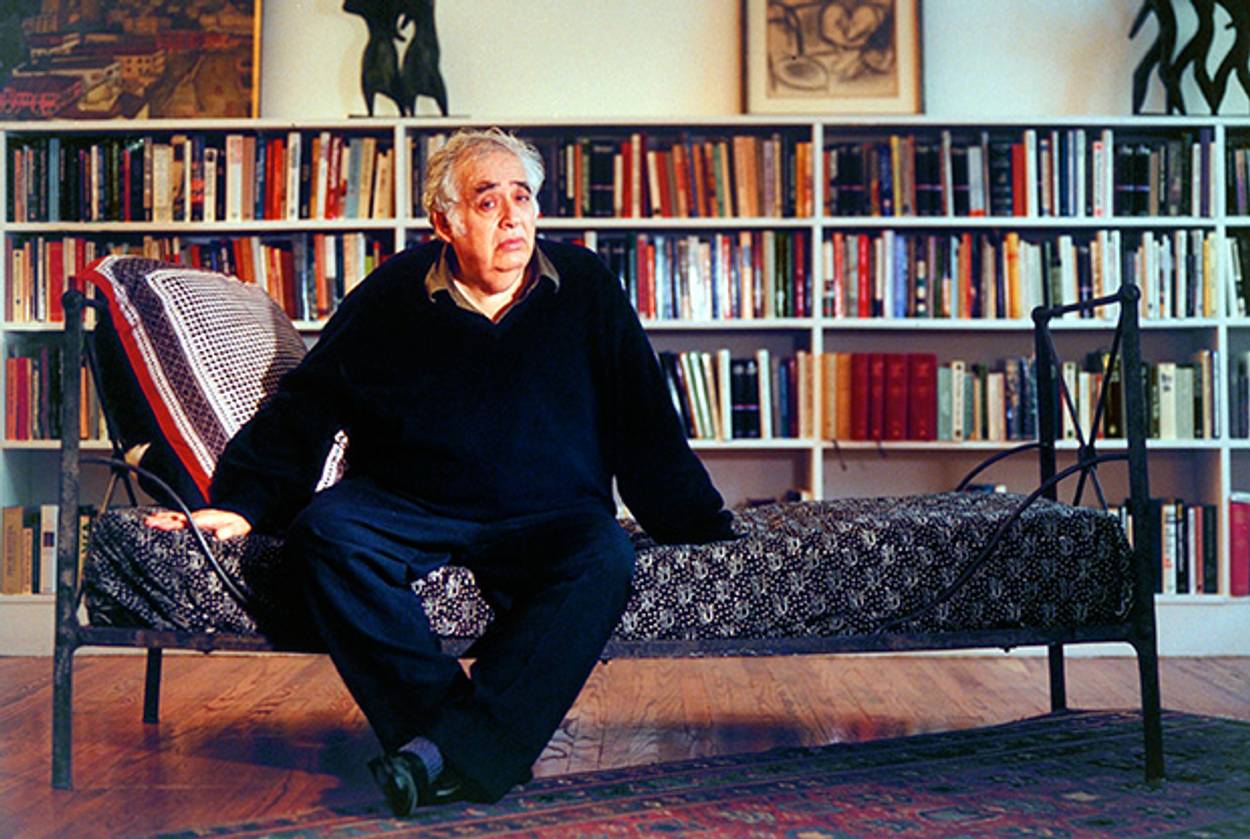

Harold Bloom Is God

A conversation about literature, Judaism, and the Almighty with the great Yale literary critic

In the summer of 2002, the agile Dominican superstar Alfonso Soriano became the first New York Yankee in history to notch 30 home runs and 30 stolen bases in a single season. Soriano broke another record that year: He was the first Yankee to strike out 157 times in a season. Asked to explain his habitual wild swings, Soriano produced a great line: “You don’t get out of the Dominica by taking pitches.” In New Haven, the world’s most famous literary critic, Harold Bloom, murmured his approval of Soriano’s statement to friends. Bloom has been a Yankees fan since he was a kid growing up in the impoverished, heavily Jewish East Bronx of the 1930s, and so he applied Soriano’s adage to himself: “You don’t get out of the East Bronx by taking pitches.”

Indeed, Bloom has had his share of furious swings; at 82, he’s as much a firebrand as he ever was. A year ago, he attacked Mitt Romney in the New York Times as the standard-bearer of a money-hungry oligarchy known as the Mormon Church. Twenty years before, Bloom made many Mormon friends by praising Mormon founder Joseph Smith as a “religious genius” in his lively, remarkable book The American Religion—and Bloom had come now to defend the man against an institution that he believed had betrayed him. Romney, Bloom wrote, hoped to preside over his own planet after death, “separate from the earth and nation where he now dwells”: His faith promised him “a final ascension to godhead.”

Bloom was born in 1930, son of a Yiddish-speaking family that would lose dozens of relatives in the Holocaust. Yiddish was Bloom’s first language, and he had the usual Jewish education at the prompting of his observant mother, but he resisted traditional study from the beginning. “I haven’t got a Talmud at all,” he told me. “If there were such a thing as a Talmudic Orpheus, I might qualify as that, but otherwise, no; Kabbalah, rather.” Normative Judaism, Bloom continued, is “a peculiarly strong misreading of the Tanakh done in order to meet the needs of a Jewish people in Palestine under occupation by the Romans. What it has to do with 2012, search me … it’s a fossil.” Yet Bloom also disagrees with Irving Howe’s famous assessment that, with Yiddish largely dead, Jewishness now means either religion or Israel. “I didn’t believe that and I still don’t, not that I can tell you what [Jewishness] is—it’s undefinable.”

Though Bloom has always stressed the central fact of his Jewishness, it has always been blended with his deep sense of Romantic imagination. By the age of 10, Bloom says, he was already deserting the Talmud for Hart Crane. Since then, he has followed the radical leanings of British Romantics like Blake and Shelley, poets Bloom, more than anyone, helped return to the literary pantheon. Behind Blake and Shelley are the Hebrew prophets, who are determined to explode rotten conventions and pious hypocrisies. In his 40s, Bloom discovered Kabbalah and become close friends with Gershom Scholem; later on, he professed his belief in the ancient sect of Gnosticism, which has attracted many Jews. His love for the intimacy that occurs between a serious reader and a life-giving book comes from Romanticism but also, as he knows, from the Jewish insistence on clinging to every word, every nuance, of the Torah.

This summer, I had lunch with Bloom in his comfortable, book-cluttered New Haven home so we could talk about his long career as America’s most ardent reader of literature, the man who takes books more personally than anyone else. (I was Bloom’s student when I was in graduate school at Yale in the mid-1980s, for a course in post-Romantic Victorian prose.) We were soon interrupted by a phone call from a polite, slightly befuddled BBC reporter. The reporter asked Bloom for an on-air interview about Gore Vidal, who had died that day. Bloom swiftly agreed; Vidal was a dear friend. The voice of the BBC interviewer echoed on the other end of the line. “Something so sepulchral for such a lively fellow—a forked tongue,” Bloom muttered. Then Jonathan Spence, the eminent scholar of China and another longtime friend, called to thank Bloom for a birthday gift, a volume by the poet Keith Douglas, who was tragically killed in World War II. Spence agreed that Douglas’ poetry is just as affecting as Bloom had told him it was. (“I’m absolutely lost in these poems,” Spence told him.) Then a former student, the poet Martha Serpas, called from Oregon. Bloom had put in a request for Copper River salmon, but, Serpas said, it was “not available fresh in our area.” All around, the voices of friends enfolded Bloom.

***

The whirlwind character of Bloom’s everyday existence is the first thing a visitor notices; it’s hard to imagine how he produces his mountain of written prose, given the constant stream of visitors and phone calls. This is even more true in New York, where Bloom and his wife keep an apartment that they visit every month or so. Afternoons in New York are lively affairs, with friends constantly dropping in: writers, artists, musicians, old students. Bloom’s curiosity about everyone he meets, his sheer openness, testifies to the enormous value he places on personality. “You should hear him talk to a cabdriver,” one of Bloom’s ex-students told me. Bloom thrives on personal contact, and his conversation is full of affectionate verbal squeezes: His Yale colleague Geoffrey Hartman, like Bloom a pioneering critic of Romanticism, is the “Ayatollah Hartmeini”; John Ashbery, the poet, is always “the noble Ashbery.” Every male under 60 is addressed as “young man”; every woman, of whatever age, as “my dear.” “Kinderlach,” Bloom will say to a group of middle-aged friends, with genuine, surprised tenderness, “you astonish me always.”

As he warmed up for our interview, Bloom asked to try my frappuccino. “Give me a taste,” he asked playfully. “Perhaps it will do the old Bloom good.” Then he wanted a sip—just a sip—of Amontillado. Opera played in the background. (Bloom’s wife Jeanne is an opera buff.) Jeanne, at the other end of the table, scanning the news on her laptop, gruffly reported, “Republican compares birth control to Pearl Harbor.” (Bloom, a lifelong man of the left, said he voted for Norman Thomas.)

I asked Bloom whether the tussles of the Talmudic rabbis had any influence on him: whether their mazelike discussions presaged his idea of literary history as a fierce argument among authors. The answer was an unequivocal no. “I was a natural-born Gnostic and early on identified with a figure who is reviled in the Talmud, Elisha ben Abuya—the acher, the stranger.” Gnosticism, the age-old heresy that Bloom has embraced as his personal religion, takes to an extreme the prophetic protest against the injustice of the world. The Gnostic sees the divine as a spark within the self: a radiant imagination buried under the rock of everyday existence. This secret power rebels against the pitiless realm of fact that seems to rule our lives, the world of “schizophrenia and death camps,” as Bloom put it in Omens of Millennium. In it, he shows that Gnosticism doesn’t have to be a turning away from humanity; Bloom’s appetite for friendship certainly testifies to that.

In his youth, Bloom remembers, he felt out of place, the clumsy outsider. At the Bronx High School of Science, which he disliked (“horrible place”), Bloom finished near the bottom of his class. Then came Cornell, and his encounter with M.H. Abrams, the Romantics scholar who recently turned 100. “I was a freshman of 17. Mike was 35,” Bloom remembered. “I was very shy and awkward and tongue-tied; he made me feel at home, sweet man.” Abrams was one of the rare Jewish English professors in the Ivy League; he immediately recognized flashes of genius in Bloom. In a tribute written for Bloom’s 80th birthday, Abrams remembered that, “As a student, Harold was diffident, low-voiced … and prodigious. He read a book almost as fast as he could turn its pages, and seemed to have read everything.” Since that time, Abrams continued, Bloom has become not only “an endlessly exciting scholar and critic, but also a personage on the intellectual stage of the world,” with a resounding public voice.

Bloom went on from Cornell to graduate school at Yale, which at the time was home to a thread of anti-Semitism. “They were all down on their knees blessing the vicar of neo-Christianity, T.S. Eliot,” Bloom shuddered, as he recalled the Yale professors, “a sort of Eliotic nightmare. But you know, a young fellow, still a rough yiddishe boy from the Bronx, and a proletarian too, arriving at the Yale English Department in the autumn of 1951, was not exactly what they wanted, and I certainly didn’t want them.” But Bloom found a few outstanding teachers, especially Frederick Pottle, the brilliant Shelley scholar, who proved instrumental in Bloom’s hiring at Yale. “Pottle forced my appointment as a faculty instructor on his colleagues who didn’t want me, and they tried to get rid of me constantly, for the next seven years,” Bloom remembered. Bloom was finally tenured, in a reportedly very close vote; it was rumored that, during the deliberations, the charge of anti-Semitism was leveled against certain committee members.

In the mid-1960s, Bloom lived through a cataclysmic midlife crisis. For months, he was stricken with insomnia and unable to read. What saved him, when he could read again, was Emerson, the inescapable American Romantic thinker. Emerson is the apostle of the self that, no matter how severe the blows of fate it suffers, returns to its own light and recovers its strength. The pessimistic angel with whom Emerson competes for Bloom’s soul is Sigmund Freud, the 20th century’s far darker believer in fundamentally ironic lives: We do not—we cannot—know the truth about what we’re doing, Freud insists. Whether we are daring or cautious in our loves, these loves cannot sufficiently transform us. Every bout of eros leads us back to the parents whom we first struggled with, and who always win the battle. From this point on, Bloom became locked between Freud and Emerson in agonized, fruitful tension.

Bloom’s midlife crisis was followed by his most famous book, The Anxiety of Influence, which he wrote in a few days in the summer of 1967. The book is dense, dark, and rather infested with homemade jargon, but it shines with Bloom’s new discovery: that writers, when they create new work, always misread their precursors. In order to be original, to become who they are, they find themselves compelled to deny their literary ancestors’ true significance. The insight is a Freudian one, as Bloom knew: Earlier authors are like the parents that their children must falsify and rebel against.

The original parent, of course, is the Jewish God, who for Bloom is the strangest and most absolute literary character of them all. This God—turbulent, impatient, demanding—comes too close to the self, and such intimacy is dangerous. God nearly murders Moses and asks for the life of Abraham’s beloved Isaac as well. Later Jewish tradition retreated from the sublimely unpredictable God of Genesis and Exodus when it invented a law-abiding, compassionate deity, but the earlier vision, in its unrivaled potency, remains more memorable. The earliest strand of the Bible has at its center a God of uncanny strength, an astounding, and potentially lethal, personality, and Bloom remains magnetically drawn to this provoking, more-than-human figure.

In The Book of J, Bloom’s first foray into biblical criticism, published in 1990, he dropped a bombshell. He speculated—no, he asserted—that the first author of the Hebrew Bible, known by scholars as the J writer, was a learned woman at the court of King Solomon. It was a spectacular, and utterly ungrounded, fantasy, but it propelled Bloom’s Book of J onto the best-seller list.

Behind the strict superego that Moses called down on his stiff-necked Israelites is a far weirder deity, Bloom suggested, less a reality principle than a fantastic imaginative power. In The Book of J, the biblical scholar and critic Herbert Marks told me, Bloom sees the Jewish God as “a willful urchin,” in a way that is “at once demystified and magically compelling. No previous interpreter, religious or secular, ever caught that note. It took Bloom’s unique combination of sensitivity and chutzpah,” Marks concluded, to remake our sense of the Bible in this daring, cheeky manner. Bloom may not be the most scholarly reader of the Tanakh, but he is one of the most deeply, even shockingly, intuitive.

***

Bloom approaches all books the way he approaches the Bible: He likes to burrow rapidly through the words on the page, because he needs to find the stance of the soul that speaks the words. David Bromwich, who studied with Bloom in the 1970s and is now a vital critic in his own right, remembered that when Bloom taught a poem, he liked to get inside it the way an actor gets inside a role. (I remembered him this way, too.) Bloom would arrive to class 10 or 20 minutes early and then sit chatting with students and feverishly turning the pages of whatever book they were to discuss that day, Ruskin or Ashbery or Oscar Wilde. He reminded one friend of Paddington Bear; others noticed a resemblance to Zero Mostel or Alastair Sim. When Bloom taught, he rhapsodized; when we interrupted his touching and often funny monologues, he always knew right away what we meant and never broke his verbal stride. In his well-worn longshoreman’s sweater, clutching his chest with one hand, sparse hair flying, he found hidden places in the text, imaginative secrets he had been brooding over, it seemed, for years. Emerson instructs us to “read for the lustres,” and Bloom did just that.

Being a Jew becomes for Bloom an emblem of the lone self, brooding powerfully over its status as wanderer and outcast.

Bloom has taught in Israel, though not for many years. He told me that, when he lectured in Jerusalem in 1960, he kicked a 44-year-old Moshe Dayan out of his class. (Dayan, instead of paying attention, was flirting with a girl.) He esteems Israeli writers, especially David Grossman. But his truer love is for Yiddish rather than Hebrew literature. “The first literature I really appreciated was Yiddish literature,” Bloom said. “The first secular poets I really cared for were Moishe Leib Halpern, Yankev Glatshteyn, Mani Leib, H. Leivick.” Halpern, he said, was “the best of them; the Yiddish Baudelaire, as he was called.” As Yiddish culture waned, Bloom came to praise the works of Jews writing in English, especially Philip Roth, whom he has called our greatest living novelist. He seems particularly moved by Roth’s rebellious creativity, so passionate in its scorn for all that is wholesome and acceptable, including mainstream Judaism. Yet Roth, too, is unalterably Jewish. Being a Jew, a fact so hard to describe, so hidden and so crucial, becomes for Bloom an emblem of the lone self, brooding powerfully over its status as wanderer and outcast—and warring against all conventions, all the false promises that society makes.

Some of Bloom’s finest reflections have been on the loneliness of literary heroes, who he believes have something to tell us about our own loneliness. It is solitary reading alone that can save us; so Bloom announces. Solitude isolates us, but it also opens us up. In a recent book, The Anatomy of Influence, Bloom turns to a series of texts about remarkable loners: the gospel of Mark (with its Jewish hero); Don Quixote; Hamlet. Bloom invokes “Mark’s amazingly enigmatic Jesus, who is unsure who he is and keeps asking his thick-headed disciples, ‘But who or what do people say I am?’ Don Quixote in contrast says he knows exactly who and what he is and who he may be if he chooses.” Bloom adds that Hamlet doesn’t want to know who he is (does he fear he might be Claudius’ son?) and knows what he doesn’t want to be (a stage avenger drenched in blood).

So the mind races: We suddenly compare Mark’s Jesus to Quixote to Hamlet. Bloom’s rapid-fire illuminations take us from Romanticism to religion and back again. The critic has rescued us from drab, conventional existence. The fame- and money-centered dreams we think will satisfy us; the complacent trust in worldly status; the institutional solidarity of trend-spotting professors: All this finds its antidote in Bloom’s restless, abundant habits of reading. Bloom’s continued relevance is that he is still our most inspirational critic, still the man who can enlighten us by telling us to read as if our lives depended on it: Because, he insists, they do.

David Mikics is the author, most recently, of Stanley Kubrick (Yale Jewish Lives). He lives in Brooklyn and Houston, where he is John and Rebecca Moores Professor of English at the University of Houston.