Hello Darkness, My Old Friend

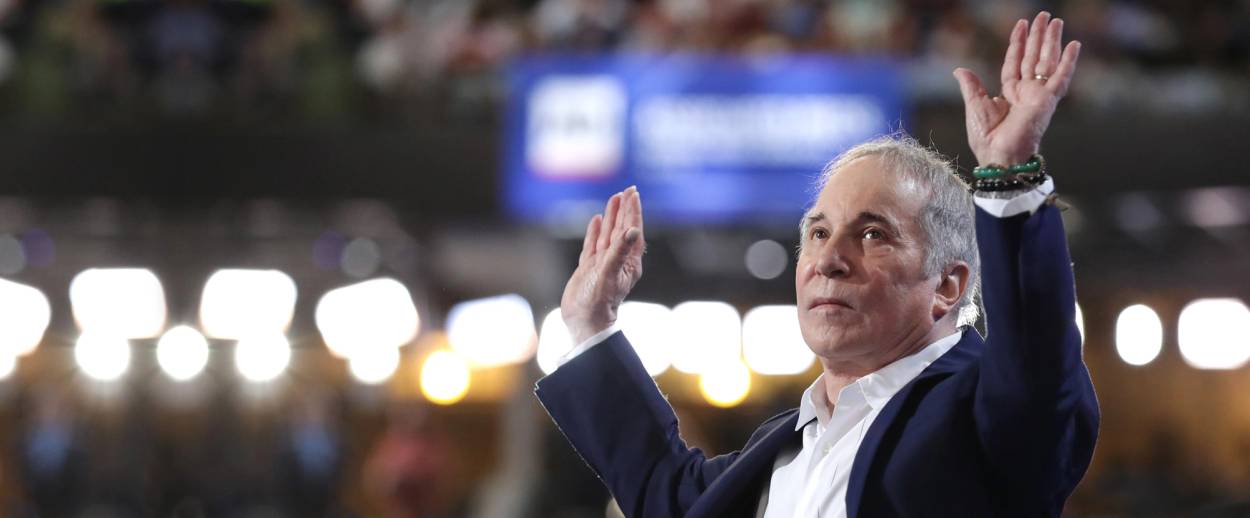

It has never been easy, even with all the accolades, to be Paul Simon. A new album, ‘Stranger to Stranger,’ shows the popular bridge-builder is still crazy after 74 years.

On “Wristband,” the first single from Stranger to Stranger, Paul Simon’s 13th solo album, Simon sings about being lost. This is not a new theme for him. It goes back as far as “Hello, darkness, my old friend.” And this is not a serious allegory on the level of his canonical songs from decades ago, including “America,” which he recently donated to the presidential campaign of fellow New York Jew Bernie Sanders, also 74—in an ad that was reprised at the Democratic National Convention this week. This isn’t about the meaning of our nation or love or anything deep. It is about being locked out of your own concert. The show must go on, but you are the show, and a 6-foot-8 bouncer tells the 5-foot-1 Simon that he can’t go on at all. “I don’t need a wristband,” sings Simon in mock umbrage. “My ax is on the bandstand, my band is on the floor.” All of this is powered by a Latin-tinged upright bass and eccentric Afro beat. And the inimitably neurotic humor of Simon.

Yes, he definitely belongs there, but why is he locked out? Perhaps he’s finally had enough. Simon says that whenever he finishes an album, he considers never making another one again. But Simon is now in his seventh decade, and he has to wonder. He knows his voice has held up remarkably well, that his search for new harmonies (in Harry Partch’s microtonal instruments—based on 43 tones instead of 12—which he uses on a few songs on this album) and unexpected rhythms and new rhymes could conceivably keep going on for a while. But he’s been thinking of the pop song form since he was around 13 and fell in love with doo-wop harmonies, and that was quite a while ago now. (When Simon received the Gershwin Award from the Library of Congress he found, in Simon’s father’s handwriting, the copyright for his very first song, “The Girl For Me,” from this period.) Should the rest of his life be dictated by his adolescent dreams? Simon has said that he wants to look into some spiritual form of expression that doesn’t involve songs.

The truth is that Simon has been here before. He has, in fact, tried branching out—to film, in One Trick Pony (1980), which he wrote and directed under a pseudonym, a slight movie redeemed by memorable performances from Rip Torn and Lou Reed, along with, of course, a kick-ass soundtrack. And then there was his biggest failure, the Broadway flop The Capeman, co-written with Nobel laureate Derek Walcott, who could not save it. The songs were better received when they were performed on their own. And so, it seems when he tries to escape the songs, he finds himself confronted with them again. Whenever his ambitions have led him astray, they have always been his saving grace. And they are remarkable on this album; the darker and more eccentric, the better. Yet Simon gets bored with standard rhythms and typical themes; he gets bored with repeating the fascinating thing he did last time. Pick your favorite Paul Simon album and you will find it has no sequel. “Keep the customer satisfied,” he sang on the final Simon and Garfunkel album, which sold over 25 million copies. The customers still line up, but the only one that matters is Simon himself.

And so now he has given us 37 more minutes of music that passes muster. He’s his own toughest crowd. He has won every conceivable award a musician can win. And the ambition to win those awards is palpable in some of his most well-loved songs. He felt it with “The Boxer” or “Bridge Over Troubled Water” or “American Tune.” These are big, bold songs with grand themes and uplifting drama, as ambitious, in their way, as Irving Berlin writing “God Bless America.” (“Bridge” and the man who wrote it were trotted out in Philadelphia to mend the alleged rift between factions of the American left.) But since the fiasco of The Capeman, Simon has increasingly turned toward his own need to discover new pastures. What he called the “rhythmic premise” of You’re the One (2000), collaborating in the sonic landscape with Brian Eno on Surprise (2006), and then finally entering what will be regarded as a truly inspired late period, on the level of Stevens or Yeats in their later years: the majestic So Beautiful or So What (2011) and now the dark, brooding, and thoroughly absorbing Stranger to Stranger.

***

Two of the songs on the new album, “Street Angel” and “In a Parade” are narrated by a schizophrenic. “The Riverbank” was inspired by America’s wars and the Newtown massacre; Simon played at the funeral of one of the teachers. The opening song, “Werewolf,” begins with an obscure Indian instrument that makes an exotic “boing” sound before the clap drums set up a joke with wordplay and, out of nowhere, murders its protagonist:

Milwaukee man led a fairly decent life

Made a fairly decent living

Had a fairly decent wife

She killed him—sushi knife

Now they’re shopping

For a fairly decent afterlife

What begins as banality suddenly becomes fatality, then all the fairly decent stuff leads to more shopping—for the hereafter. Then we learn that “most obits are mixed reviews”—not just those who are murdered by their wives. The wordplay continues. “Life is a lottery, a lot of people lose.” There is the mass of a lot of people and the lottery of life—so much comes down to luck. We know this, yet we need a sage of song to tell us, and seduce us with rhythms and exotic textures before he plays it for maximum darkness. This “hello, darkness” thing is getting real.

And Paul Simon becomes most vivid and inspired when taking on the voice of a schizophrenic man. Somehow, the role liberates him. He’s not the suburban husband and father in New Canaan, the guy with all the Grammys, the Kennedy Center Honor, the Gershwin. He’s a schizo drugged up on Seroquel and sent out to walk the Earth. This somehow clarifies the occupation behind the character: songwriter. It’s the thing that he thinks he might outgrow on his way to some sort of spiritual older age. And yet, the Street Angel is too far gone to realize he’s a wreck. This just brings out his ebullience:

I make my verse for the universe

I write my rhymes for the universities

And I give it away for the hoot of it

I tell my tale for the toot of it

I wear my suit for the suit of it

The tree is bare, but the root of it

Goes deeper than logical reasoning

When you’re writing your rhymes for the universe, it’s sort of a bigger deal than being a rock star. You are the canon itself. You are larger than death. You will resonate forever. Forget the Ticketmaster charges. The Street Angel comes back in “In a Parade.” Simon is singing without a guitar, just drums. He sounds absolutely free. He doesn’t have to worry about playing in any patterns he’s played in before. It’s a new beat, something he can play against. “I can’t talk now, I’m in a parade” goes the anaphora, a celebration too loud for the smartphone. And then suddenly, he wears the uniform that inspired Black Lives Matter:

I drank some orange soda

Then I drank some grape

I wear a hoodie now to cover my mistake

My head’s a lollipop

My head is a lollipop

My head’s a lollipop and everyone wants to lick it

I wear a hoodie now so I won’t get a ticket

The imagination and the headlines collide and call it a truce, or at least a misdemeanor. “I write my verse for the universe,” he declares. In “Street Angel” he said he made his verse for the universe. Now he’s saying he’s writing it. It is inscribed either way.

Even though Paul Simon has mused about doing something beyond songwriting, what he is likely to do is take songwriting even further. He said that even as he sees how long he can go without writing a song, he still can’t be without his guitar for too long. Let’s not pressure him. One of the joys of Paul Simon’s last two albums has been his liberation from the audience. He’s beyond trying to please anyone, no matter what he might say about keeping up with Kanye or Kendrick. Let’s just leave him be. It’s possible that he could pull a Philip Roth and scrawl a note on his computer screen: The struggle with writing is over. But then Paul Simon has also said that what he does is way too fun to call it a job. Novelists write in solitude. Roth had breakdowns between the books. It gave him great relief to scrawl those words. But unlike Roth, Simon has a loving family around him, musicians to work with, adoring crowds to sing for. It’s not such a terrible life, really. He sounds like he’s in a good mood when he’s thinking about Cool Papa Bell, a baseball player from the Negro Leagues who was known as “the fastest man on Earth.” And it gives him a moment of grace before he undercuts it:

Every day I’m here, I’m grateful

And that’s the gist of it

Now you may call that a bogus

Bullshit, New Age point of view

So which is it? He invites you to check out his tattoo. It says “Wall-to-Wall fun.” We know this is another joke. It has never been easy, even with all the accolades, to be Paul Simon. It has certainly not been wall-to-wall fun. It has been sometimes agonizing to find the right sounds and the right words to get any kind of fun—or any other kind of feeling—across. Just look at some of the instruments in the credits: Hadjira, TrombaDoo, Big Boing mbira, Chromelodeon, zoomoozophone, Cloud-Chamber Bowls, Harmonic Canon. Some of these are Harry Partch’s instruments, stored at Montclair State. Some are imports from various places of the world. Paul Simon’s favorite rock ’n’ roll song will always be Elvis Presley’s “Mystery Train.” But these instruments and the way he uses them keep the mystery chugging, one eccentric note and beat at a time.

Indeed, the word “perfectionist” would not even begin to cover how much Simon agonizes over finding the perfect sound—and the perfect silence. He hires great players and then tells them not to play so much. He’s not doing this to be a pain in the ass—that may be the result, but it is not the purpose—but because he is making something with great precision, and where musicians want to blow, he wants space. Put that rhythm here, that riff there, then switch it again. And then each line must not be a cliché or an attempt to re-create an earlier success.

On the title track, Simon makes it seem deceptively easy:

Words and melody

So the old story goes

Fall from summer trees

When the wind blows

If only. That is the stuff of fiction, perhaps what Wallace Stevens would call a supreme fiction. Later in the song, Simon reveals something that is likely more accurate:

I’m just jittery

I’m just jittery

It’s just a way of dealing with my joy

Simon’s tendency to check in with us every five years gives him plenty of time to fine-tune. And he’s not sure if he’s going back there. He’s dealing with his joy, but he’s jittery. Paul Simon is still crazy every five years or so. Let’s not give him an encore. Let’s just let him do whatever he feels like. Roth said that when he looked at the fridge and saw that declaration—the struggle with writing is over—it gave him strength. It’s a loss for us, but it seems to make him happy, for now, and it gives him time to micromanage his Wikipedia page and talk to his biographer. It’s hard to believe that Rhymin’ Simon is ready to pack it in yet. Again, on “Stranger to Stranger”:

All in good time

Although most of the time

It’s just hard working

The same piece of clay

Day after day

Year after year

Certain melodies tear your heart apart

Reconstruction is a lonesome art

Yes, we know it’s lonesome, and yet we know it’s too fun to be a job. Rest, rest, perturbed spirit. If we’re lucky, Paul Simon, we’ll hear from you in five years. You will tell us, with chords, rhythms, and rhymes that don’t even exist yet, something that you predicted on “Bookends” way back when you were harmonizing with a guy called Art, except that you will raise it by a decade: How terribly strange it will be to be 80.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today

David Yaffe is a professor of humanities at Syracuse University. He is the author, most recently, of Reckless Daughter: A Portrait of Joni Mitchell. Follow his Substack: davidyaffe.substack.com.