An African in America

The Nigerian (soon to be American) writer on racialism, postcolonialism, and inequality—and the power of literature

I have heard many an African say that they never knew they were Black till they came to America, or to Europe, and only then did they realize that all along they had been Black. It is like Adam and Eve suddenly discovering they are naked; like childhood suddenly coming to an end—nothing will ever be the same again.

There is an anecdote in Zora Neale Hurston’s Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), when the narrator, Janie, at 6 years old, suddenly discovers her Blackness. She lives in an unsegregated household in Florida with her grandmother who works for a liberal white family; all the kids in the household are white except her, they all play together, one day a photographer takes a picture of the kids at play and when the developed picture comes, every child easily identifies himself or herself in the photo, except Janie. Finally, Janie comes to the shocking conclusion that the unidentified colored girl in the picture has to be her: “… before Ah seen de picture, Ah thought I was just like the rest,” she said.

Such cognitive dissonance illustrates so well the idea of race being a construct. We were all simply human beings before we became a racial category, before someone decided there is benefit in classifying human beings into hierarchies and groups, with the white man at the top, and the Black man at the bottom.

Ask any African in America and he or she is sure to have a ready “discovering my Blackness moment” anecdote. Most of these anecdotes involve the authorities. A friend told me how, on his very first day in America, he was stopped by the police for suspicion of robbery—it appears a robbery had just been called in and the perpetrator matched his description: young, Black, male.

For me, it was 2004. I was visiting New York for the first time. I was in the subway and I needed directions and so, logically, I walked up to a policeman standing by the turnstiles, as I approached I saw him tense, his eyes focused on my face, unsmiling, and as I got closer I saw his hand drop to his gun. I stopped and stammered my question—I was looking for the north exit. “Keep moving,” he told me coldly. All I saw was a policeman whose job should be to assist. All he saw was a young Black male approaching him. It is in his DNA as an American policeman to see me as a threat.

In her brilliant essay “The Long Blue Line” in The New Yorker, Jill Lepore outlines the antecedents of policing in America, tracing its roots in slave patrols, Jim Crow, and culminating in Mayor Rudy Giuliani’s stop-and-frisk and the continuing violence against Black people by the police today, concluding that policing in America mostly means policing of Black and brown bodies, immigrants, and the occasional union busting. She referenced the 1680 slave codes that explicitly granted any white man the right to capture and even kill any runaway slave. All citizens, meaning whites, had the legal right to “apprehend and take the said negroe,” and if the Negro resisted, “then in case of such resistance, it shalbe lawfull for such [white] person or persons to kill the said negroe or slave. …”

Of course, Africans, like Janie, always knew they were Black—they just never knew that they were supposed to feel inferior because of their skin color. Most of them, especially from West Africa, grew up in racially homogenous societies. Colonialism was a long time ago. They went to all-Black schools and worked in all-Black offices. The richest people they have ever met, and the most powerful, including the police and the politicians, were all Black. Being Black was neither a relative nor a disadvantaged state, it was the normative state. They had not learned to associate color with privilege in an experiential sense. They had no idea they were supposed to be ashamed of the color of their skin; on the contrary, they were brought up to be proud of their culture and their Blackness.

Most African immigrants at first find it hard to make sense of America’s racialism, and so rather than engage in the racial warfare, they try to ignore it. They keep to their communities. They keep a distance from the African Americans who should be their natural allies; they find it easier to make friends with liberal whites than with African Americans.

Africans cannot become African American in the way an immigrant from Asia can automatically become Asian American, or an immigrant from Italy can become Italian American. Yes, they are regarded by the police, by the power structure, as Black, but they always see themselves as Ghanaian American, or Nigerian American, or just as African, but not African American. Their children can become African American—a good example would be America’s first Black president, Barack Obama, the son of a Kenyan father who grew up as an African American. They see themselves as here temporarily; they are here to work, to build a little capital, to take advantage of the opportunities America offers, opportunities they can never have back home, before retiring back to Africa.

But of course most of them never make it back—they can’t go back because they don’t fit in at home. America has become their physical home while their native country will always be their mental home. They live in a state of divided loyalty, a sort of immigrant limbo.

I have lived in America for about 13 years now, and only this year have I been able to write a short story set in America. This is not because I felt I hadn’t earned the right to write about my American experience—though it is partly that—but it is also a reluctance to turn my back on my native country, Nigeria. First I had to convince my psyche that America is where I live, and because I live here I have not just the right but also the duty to write about it.

No racial group in America has a history as unique and singular as that of the African American. To become African American one has to share in the history, the culture and the total experience of being Black in America. What is Kwanzaa? When is Juneteenth? I had no idea what Black History Month was until I came to America.

Simply being Black, or being discriminated against, doesn’t make you African American. From slavery to emancipation to Jim Crow to civil rights, African Americans have engaged in a perpetual struggle against a system designed to keep them down. In “Black Matters,” a chapter of her book Playing in the Dark, Toni Morrison explains how most American institutions and literature are shaped by, consciously or unconsciously, reaction to the Black presence. If America is a melting pot, she asserts, Black people are the pot, all the other races are united inside the pot in opposition to Blackness.

Perhaps Morrison’s most penetrating illustration of the Black experience in America is in her protagonist character, Sethe, in Beloved, an escaped slave who decides to kill her own children rather than have them returned to slavery. In America, famed for its opulence and material plenitude, where the very definition of the American dream is to achieve material success—house, cars, money in the bank—the Black man is resolutely and ruthlessly denied access to this dream. Like Sethe, the Black man must learn to love in tiny bits. He cannot love too much or hope too much because that which he loves can be taken away from him at any given moment by the authorities. And so the very definition of the Black experience in America is one of negation: The Black man and woman are defined not by that which he or she can become, but by that which he or she cannot become.

And yet, despite the shackles, the Black person persists, creates music, science, literature, community, even under this symbolic knee pressing down on his neck. “And still I rise,” Maya Angelou wrote.

Langston Hughes says it all in these lines:

America never was America to me,

And yet I swear this oath—

America will be!

Many parallels can be drawn between the African’s experience of colonialism and the African American’s experience of slavery. Both systems were designed to subjugate and dispossess the Black man—in Africa, the native. Both systems revolved around the three pillars of land, labor, and culture. Take away the land from the native, or, in the case of slavery, take the native away from the land; compel the native to work the stolen land for the benefit of the master; and finally, destroy the native’s cultural and historical pride by making him believe that he is inherently inferior to the colonizer or slave master.

Of these three factors, the cultural is the most insidious and the most harmful. No slave master or colonizer can succeed in suppressing another human being for a sustained period of time unless he is able to convince that person that he deserves to be suppressed. For the African, this cultural brainwashing is the origin of the politics of postcolonial guilt and shame. It doesn’t happen overnight, it is the product of decades of indoctrination work by the colonizer, of colonial administrators working in tandem with missionaries and schools to convince the African that his gods are worthless idols, his religion mere superstition, and that he has no history before colonialism—in fact, that everything that existed hitherto was one long, dark night from which he has been mercifully rescued by colonialism, or slavery.

But long before he convinced the colonized and the enslaved of their inferior status, the European had to first convince himself of his superiority by inventing race. “There is the desire—one might indeed say the need,” wrote Chinua Achebe in his essay, “An Image of Africa,” “in Western psychology to set Africa up as a foil to Europe, as a place of negations at once remote and vaguely familiar, in comparison with which Europe’s own state of spiritual grace will be manifest.”

Both slavery and colonialism depended on confining the Black person, policing his movements. The first thing the colonizer did in South Africa and Zimbabwe and basically every colonized territory, was to herd the natives into townships, native areas, and forbid them from venturing into white areas unless they were domestic workers, and even then they must carry a pass, the same way that the slave couldn’t venture out of the plantation without a note from the master.

But policing the body was never enough. The mind had to be policed, too, for the mind can wander further than the body ever can. In the process of policing the mind, untold damage was inflicted on the Black man’s psyche: Scientists have shown that trauma associated with terrors such as that suffered by the colonized and the enslaved can affect even future generations who didn’t experience these terrors firsthand, modifying their behavior in the way they respond to stress and other stimuli. But the most obvious of these lingering effects is in the health of Black people, making them more prone to suffer from certain diseases compared to other races. A study found that older Black people born during the civil rights struggles and Jim Crow in the so-called Stroke Belt (Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee) even if they don’t live there anymore, are more prone to mental diseases such as dementia and Alzheimer’s than the rest of the population.

The inability of the newly independent African nations to work, and the failure of African Americans to get ahead in America, is often pointed to as evidence of the Black person’s innate inferiority, a sort of genetic predisposition to fail. This often sadistic accusation ignores the fact that colonialism, like slavery, did not simply end with independence or with emancipation. Africans are still grappling with neocolonialism just like African Americans are grappling with institutional racism. In Africa, multinational corporations have stepped in where colonial administrations stopped.

A good example is Nigeria’s Niger Delta, one of the largest wetlands in the world, once home to a variety of animal species now mostly destroyed by oil companies while the natives watch helplessly as their sources of livelihood, fishing and farming, are taken away. These companies can’t be sued by local communities or African governments; they can make or unmake governments; they foment civil wars and oust sitting presidents. Britain and France, and other former colonial countries, still insist on preferential trade and economic agreements with their ex-colonies—to the perpetual detriment of these ex-colonies.

The artificial national boundaries that created the new African nations were drawn in 1884 in Berlin by European powers so they could exploit these territories without resorting to conflict among themselves. The African is trapped in Europe’s imperial web just like the African American is trapped in the legacy of slavery.

“The very serious function of racism … is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being,” says Toni Morrison in her 1975 lecture “A Humanist View.” This is true, but the work of dismantling the legacy of slavery and colonialism is as urgent today as it ever was, not just for the benefit of the Black man, but for the benefit of the white man as well.

The Black person has been described as the perfecter of the American ideal. His struggles for equality will always bring America nearer to its founding principles, that all men are created equal. And of course one of the most obvious beneficiaries of the African American’s struggles against injustice is the African—every freedom, every benefit enjoyed by every Black man in America today is because of these historic struggles for justice. One of the most potent tools for fighting historical discrimination—and I say this because I am a writer—is literature, and the arts in general. They work on the mind in a way other tools of decolonization cannot. Literature’s effects are deep and subtle and they can change the mind not just of the Black man, but also of the white reader, by creating empathy, by making the oppressor stand in the shoes of the oppressed, by systematically refuting, in imaginative and creative ways, centuries-old claims about the innate superiority of one “race” over another.

All good literature, I believe, is an act of resistance. Resisting the status quo, resisting bad taste, resisting evil, till at the end the reader is hit with an epiphany, like Saul on the road to Damascus. While the media and the movies daily try to sell us the American dream of limitless opulence and possibilities, the writer challenges this glossy narrative by showing the ugly underbelly of American society—from Stephen Crane’s Bowery stories to Hemingway’s manly adventures to Colson Whitehead’s underground railroads, literature dares us to step outside our bubbles and see that the world doesn’t necessarily have to be the way we were told it should be. It can be remade.

One of the most exciting of the literatures that dismantle lies and write back to power is Afrofuturism. Exciting because, as the name implies, it has made the future its target. It seeks to place, or re-place, the Black presence into modernity.

In his essay, “Stanger in the Village,” James Baldwin claims that one of the intentions of racism is to keep the Black person outside modernity, to prove to him that he or she doesn’t belong in Europe’s history of invention and art and culture and science. In her book The Parable of the Sower, Octavia Butler, one of Afrofuturism’s founding voices, elaborates through her protagonist, Lauren Oya Olamina, the belief that humankind’s destiny is to travel beyond Earth and live on other planets, among the stars, as it were, forcing humankind into its adulthood.

Afrofuturism is the Black person’s claim to this intergalactic future, alongside other races of humanity. Not just to survive the brutal history of colonialism and slavery, and the current systemic oppression, but to thrive beyond it and make a home in the stars.

This may sound like an escapist vision, but if it is, then it is symbolic of the very need for escape experienced daily by the Black man.

I became an American resident in 2007—it seemed to me no better a time for a Black person to move to America. I saw the rise of Obama from a junior senator to the presidency, and I said to myself, only in America can this happen, the very epitome of the American dream. Terms like post-racialism were thrown about by journalists and political commentators.

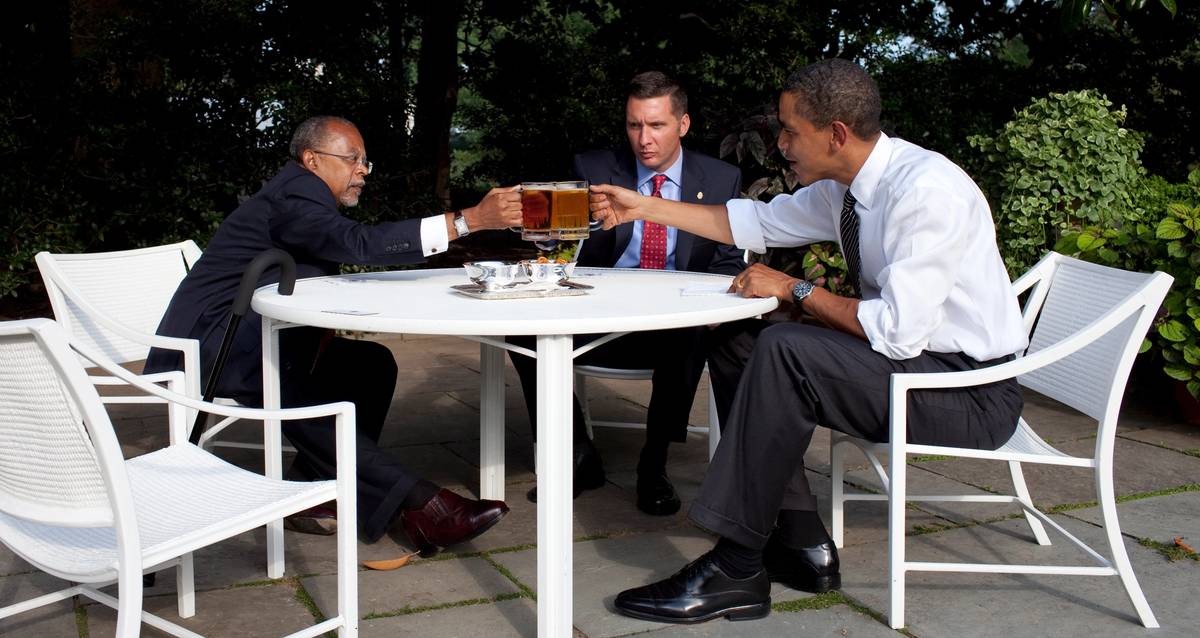

But then almost immediately the backlash began. I remember the “beer summit” in the White House in July 2009. Obama had used the word “stupid” to refer to a white cop’s arrest of a Black man trying to break into his own house because he had misplaced his keys—one would assume that a few simple questions by the policeman to confirm the Black man’s claim that this was indeed his house would have resolved the situation. Especially since, as it turned out, this wasn’t just any ordinary Black man—it was Henry Louis Gates Jr., the prominent Harvard professor and public intellectual. Obama had to not only publicly take back his words, but to also invite the cop and Dr. Gates to the White House ostensibly to broker peace—but in reality to appease white people over calling a white cop stupid. It was theater, the uppity Black man being put in his place. The status quo was reasserting itself. I knew then that my American honeymoon was over.

Donald Trump’s rise to power through challenging and undermining the very legitimacy of Obama’s right to be president stems from this buyer’s remorse. Trump’s rise is a call to action for most people sitting on the fence: a realization that if we want the America of our dreams, we have to become part of the conversation. Maybe that is why I decided to become a citizen this year, even though I had been eligible since 2015 and had never bothered to apply.

This is where I live. I cannot escape the soul searching that most Black fathers go through every day: How do I keep my children safe and also confident at the same time? I have a young son and soon, like most Black fathers, I have to have “the talk” with him. How do I make him understand that because he is more likely to be targeted by the police than his white friends, that doesn’t make him inferior in any way? How can I show him that he can be unapologetically Black in a world that is white?

The current Black Lives Matter movement protests provides some answers to these questions. It recognizes America’s imperfections, but it also shows America’s strengths. It shows that monuments erected to bigotry and injustice can be toppled, that history can be rewritten, that because you have power doesn’t mean you are right.

A democracy will always be a work in progress. The work of achieving justice and equality will always be ongoing. Justice and equality are never given, they have to be fought for, especially if you are Black.

I am happy that my children can see that it is not only Black people who are marching for racial equality, but white people as well, not just Americans, but Europeans and Asians and Africans. Ultimately, the fight for equality is not about Black versus white. It is about right versus wrong.

Helon Habila is the author, most recently, of the novel Travelers. He is also a professor of creative writing at George Mason University in Virginia.