Help, I’m a Prisoner in a Brain Lab

Alan Mittleman’s new study of Jewish philosophy ‘boils Bible stories and brain science into the message that there’s something holy in everything and everyone’—but can reason and faith coexist?

Most educated people hold radically incompatible views about humankind and nature. They believe that the brain is a mechanism governed by the laws of physics, and that not long from now brain scientists will give a complete account of human consciousness. They also believe that machines will be able to think and that everyone will have meaningful conversations with robots, not just the nerds who ask rude questions of Siri. They believe, in short, that we are the objects of deterministic physical systems akin to machines themselves, but that we can design our identities to suit our whim, down to and including our gender.

The majority of educated people embrace mutually exclusive schools of thought: a vulgar sort of 19th-century determinism on one hand, and the existentialism of Camus and Sartre on the other. It does not occur to them that their views about the mind and the human person are illogical because they do not care about logical consistency, either. Not only do they believe that everyone has their own truth, they believe everyone has a collection of different truths to be applied when convenient.

This state of affairs poses a special sort of problem for the philosopher who wants to present Jewish concepts to a broad audience—which is to say, a mainly secular one. One cannot argue from authority, for the secular audience admits of none, and one cannot argue for logical consistency, because most people do not know what it is, and would abhor it if they did.

Nonetheless, almost everyone has some kind feeling for the sacred, although few associate this feeling to a personal God. That is the soft target at which Alan Mittleman aims in his book Human Nature & Jewish Thought: Judaism’s Case for Why Persons Matter. Mittleman, a professor of philosophy at the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York, boils Bible stories and brain science into the message that there’s something holy in everything and everyone. He writes: “The sacred is not an ontological add-on to the natural world. It is the capacity of that world, as it has emerged in human beings, to turn toward, to attend to, what is highest,” whatever or whomever that might be.

***

The notion that the sacred is immanent is a popular view nowadays, but it is not a particularly Jewish one. To be sure, it was put forward by the 17th-century philosopher Benedict Spinoza, who pops up frequently in Mittleman’s account. Spinoza was expelled by his congregation and severed his ties to the Jewish world; the question of whether he should be regarded as Jewish is poignant and difficult. Mittleman avoids the difficulty altogether. Here and at other key points in his argument Mittleman seems averse to conflict. He presents controversial assertions in sharp conflict with traditional Jewish thinking as if they were self-evident and then changes the subject without bothering to defend it.

Mittleman worries that “Judaism risks intellectual irrelevance by failing to engage with the challenges of contemporary thought.” This statement is a bit slippery. Traditional Jewish sources (most of which Mittleman ignores) have engaged the foundational problems of modern science for centuries. Not only have they engaged, they have exercised an important influence on science itself.

Spinoza is a case in point. He was not only a bad Jew but a very bad philosopher. As both G.W. Leibniz—the coinventor of calculus—and later Hegel observed, Spinoza’s immanent God collapses all individuality into his single infinite substance; it cannot explain why different things exist. Leibniz, one of history’s great scientific minds, thought that Jewish philosophy had great importance for science. He wrote in 1706 (in a letter to Foucher de Careil) that Spinoza’s “monstrous system” suffered from his failure to understand Kabbala.

Leibniz had in mind Rabbi Isaac Luria’s concept of tzimtzum, or contraction: God contracted himself in order to make room for the universe. Leibniz’s ontological treatise “Monadology” shows Luria’s influence. Disturbing as that may be to a modern audience, the rabbinic account of nature and man was an inspiration to the 17th-century revolution in mathematical physics.

The problem of free will occupies the longest and most important chapter in Mittleman’s book. To be a person implies the ability to choose. Physical systems are by their nature deterministic, even if they entail a degree of randomness and exclude the possibility of choice. Brain science considers the mind as a physical system. Mittleman wrestles with the problem and at length allows himself to be pinned to the floor. Determinism wins in his account: “From the neurobiological vantage point,” he allows, “the selves to which we return and freedom of choice they seem to enjoy may well be illusions. But if the self or free will is an illusion, it is a deep and peculiar one. … It might, however, be akin to the illusion of a unified visual field. … If, for the sake of argument, we consider that visual coherence and stability are an illusion, then we might have an analogy to free will as an illusion.”

If our perception of free will is an illusion lurking in a deterministic physical system, what is Judaism good for? Our choice between blessings and curses would be meaningless. If Judaism is an illusion, and all human choice is an illusion, then no illusion has pride of place in the array of all possible illusions. The Jewish idea of personhood would be an illusion as well.

Traditional Jewish sources, as Mittleman reports, are either “voluntarists” or “determinists.” But it is wrong to compare Jewish tradition with the new determinism of the brain scientists. God’s omniscience in the traditional understanding is of a different order than the human exercise of scientific reason. It is not that we lack the ability to choose, but that God, in some traditional views, knows us so well that he knows how we will choose.

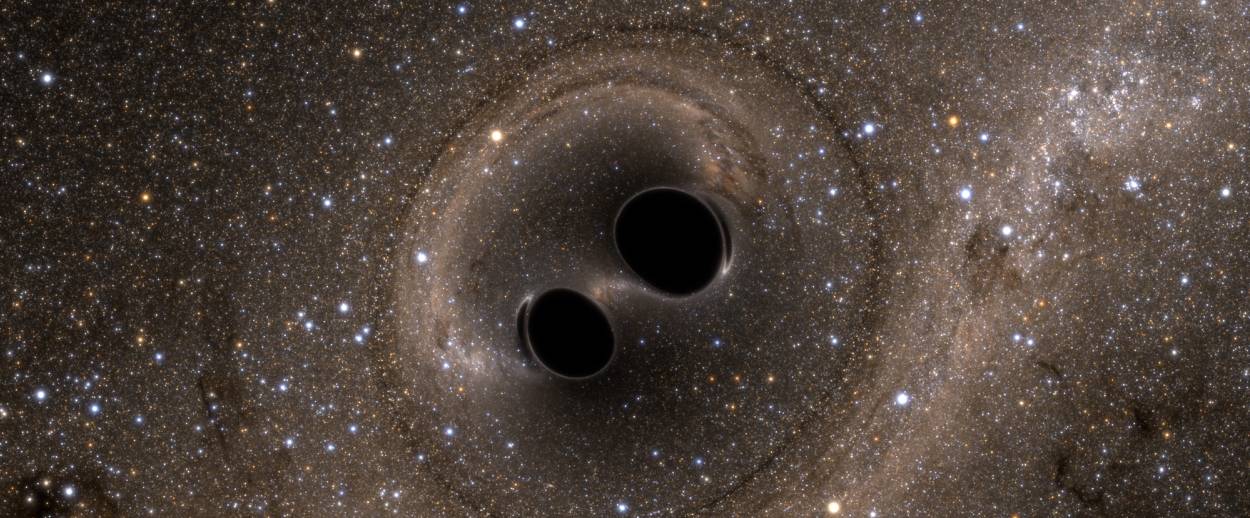

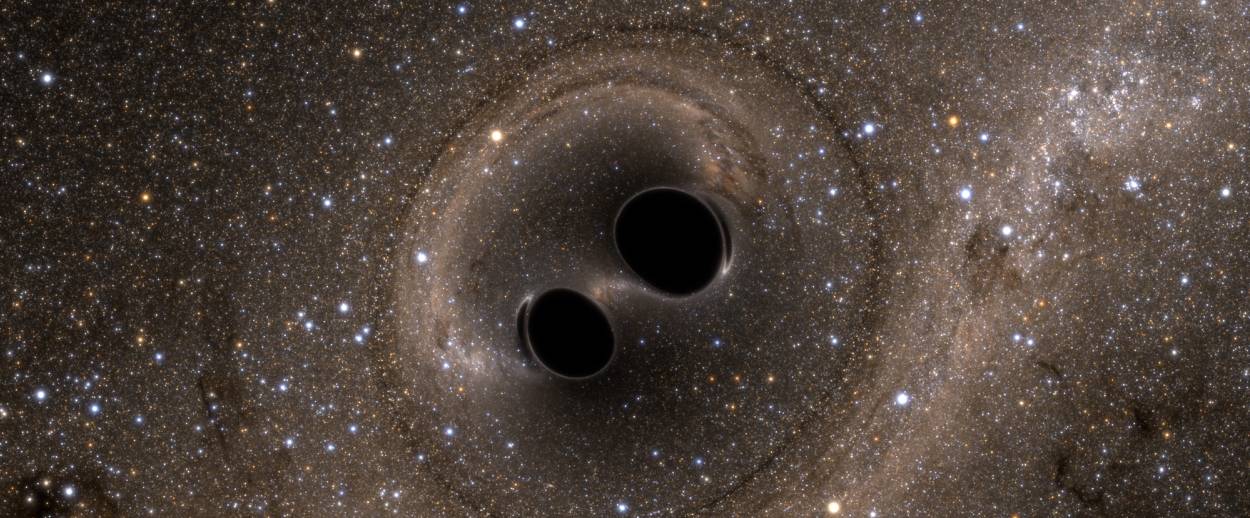

From a strictly scientific point of view, Mittleman’s awe of brain science is ill-informed and credulous. What physical assumptions underpin the transmission of information in the human brain? We cannot begin to answer the question, for determinism collapsed in physics a century ago. In the microcosm, we have the spooky world of quantum entanglement and action at a distance. In the macrocosm, we have the collapse of all physical laws in the presumed origin of the universe in the Big Bang.

The accomplishments of modern science—and its failures—have deep religious implications. In his 1944 essay “The Halakhic Mind,” Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik argued that the collapse of determinism with the advent of quantum theory made religious philosophy possible. One might add that Kurt Gödel’s 1931 Incompleteness Theorems challenged determinism at the deeper level of mathematics itself. Gödel himself believed that his work refuted the notion that machines one day might think because mathematics cannot do without intuition, an argument developed by the mathematician Sir Roger Penrose.

Science itself brings forth robust arguments against determinism. Today’s particle physics, with quantum entanglement action at a distance, offends our ordinary common sense as gravely as the imaginings of ancient theologians. Religion does not have to resort to the bland assertion of dogma to resist the claims of the new determinists: It has a great deal of science on its side. If Mittleman is aware of this history, he does not choose to tell us.

Mittleman does quote Soloveitchik, but so selectively as to mislead. Soloveitchik argued (in The Emergence of Ethical Man) that humans were part of nature, an animal like other animals but with the unique capacity to form ethical judgments. God blesses the animals but speaks to humans. Soloveitchik situates humanity within the natural world and avoids Plato’s ghostly separation of body and soul, as Mittleman observes. He wants to situate the unity of mind and body in the context of brain science but does not know how to get out of the deterministic trap. At length, he quotes neuroscientist Anthony Damasio, who “uses Spinoza’s idea of mind as ‘the idea of the human body.’ ” Damasio thinks that “Thought … is thoroughly grounded in corporeality—in perception, sensation, and mapping of body states.”

Once again Mittleman falls back on Spinoza, and with a weak argument: We cannot prove the existence of free will, but we can point to concrete instances in which actual human brains do things that brain science can’t explain. The neuroscientists have nothing to say about how the human mind conceives of higher-order geometries that cannot be visualized but nonetheless produce verifiable theories about the physical universe—for example, Einstein’s gravitational waves.

Left out of Mittleman’s account entirely is the classic Jewish formulation of the problem of human freedom. If the Creation were perfect, argued Rabbi Moses Chaim Luzzato (1707-1746), free will would be impossible: Human freedom exists only because God intentionally left Creation incomplete and flawed so that humanity would have the honor to become God’s partner in finishing the work. That (and not social justice) was the original meaning of tikkun olam. The concept has deep roots in scripture (e.g., Psalm 102:25-27), in rabbinic tradition (Rabbi Akiva’s defense of circumcision as an improvement upon flawed nature), and liturgy (the blessing for the New Moon, which envisions the repair of defects in the cosmos). This theme pervades the work of Joseph Soloveitchik and other contemporary Orthodox writers—Rabbi Akiva Tatz, for example.

Mittleman is aware that Jewish tradition allows humankind become a co-creator with God, but his passing mention of this theme is thoroughly misleading: “Adam has also become a creator, engendering new life. After the initial creation of humans in the image of God, it becomes the responsibility of human beings to propagate the image, to represent God’s glory and majesty; in so doing, humans becomes [sic] co-creators with God.” Never did Jewish tradition equate man’s role as co-creator with mere sexual reproduction, which animals also perform. The rabbis wrote that acts of righteousness—to judge fairly, to recite the blessing of the Sabbath eve, to perform the mitzvah of circumcision—qualified man as a co-creator. Once again, Mittleman presents his own view as self-evident, at extreme variance with richly elaborated Jewish tradition, without so much as a footnote—and runs off to his next topic. This is authorial malpractice.

Another of Mittleman’s hit-and-run assertions concerns natural law. That is a concept alien to traditional Judaism. Nature itself is flawed by divine intent and therefore cannot be the source of legal authority. Yet Mittleman declares in passing that a “natural law sensibility” stands behind the seven Noahide laws the seven commandments that the rabbis taught applied to all of humanity. Two of these forbid us to curse God and to worship idols: What does this have to do with “natural law”? One can make a case that they do, but it is a complex argument, and Mittleman does not make the effort.

Abraham’s near-sacrifice of Isaac on Mount Moria is a foundational event in Jewish history, indeed the biblical story is recited in full by observant Jews in the daily morning service. The Noahide Laws also forbid murder, although as Soren Kierkegaard observed, “The fact is that the ethical expression for what Abraham did is that he wanted to murder Isaac.” As Soloveitchik wrote of the Akedah: God “wanted Abraham to abandon all pretense of possessiveness, all claims of unity and identity, all hopes of self-perpetuation and immortalization through Isaac and return him to whom he belongs.”

It is hard to square God’s command to sacrifice Isaac with natural law. The Israeli philosopher Yoram Hazony makes a serious attempt to do so. He believes that the Bible yields a uniquely Jewish form of natural law, but he is well aware this requires a new interpretation of the Binding of Isaac—and he offers one. I disagreed with Hazony when I reviewed his book on the subject in this publication, but he did give the issues their proper due. Mittleman, by contrast, pitches a stone through the front window of Jewish tradition and runs away. He should know better.

Mittleman leaves us with bad Judaism and bad philosophy. Starting with Kant, philosophy promised to teach epistemology and ethics without recourse to religious authority. They were fools, Nietzsche objected: They killed God. By the 20th century, secular philosophy ceased to claim authority in ethics. It diverged into logical analysis, which had no interest in the subject; and existentialism, whose two greatest exponents, Heidegger and Sartre, substituted “authenticity” for ethics. The two great existentialists set a poor example; they respectively embraced Hitler and Stalin. Philosophy of science, meanwhile, stands baffled before the chaos of quantum physics and cosmology. The notion that white-coated technicians in the neurology lab will succeed where the philosophers failed seems fanciful.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

David P. Goldman, Tablet Magazine’s classical music critic, is the Spengler columnist for Asia Times Online, Washington Fellow of the Claremont Institute, and the author of How Civilizations Die (and Why Islam Is Dying, Too) and the new book You Will Be Assimilated: China’s Plan to Sino-Form the World.