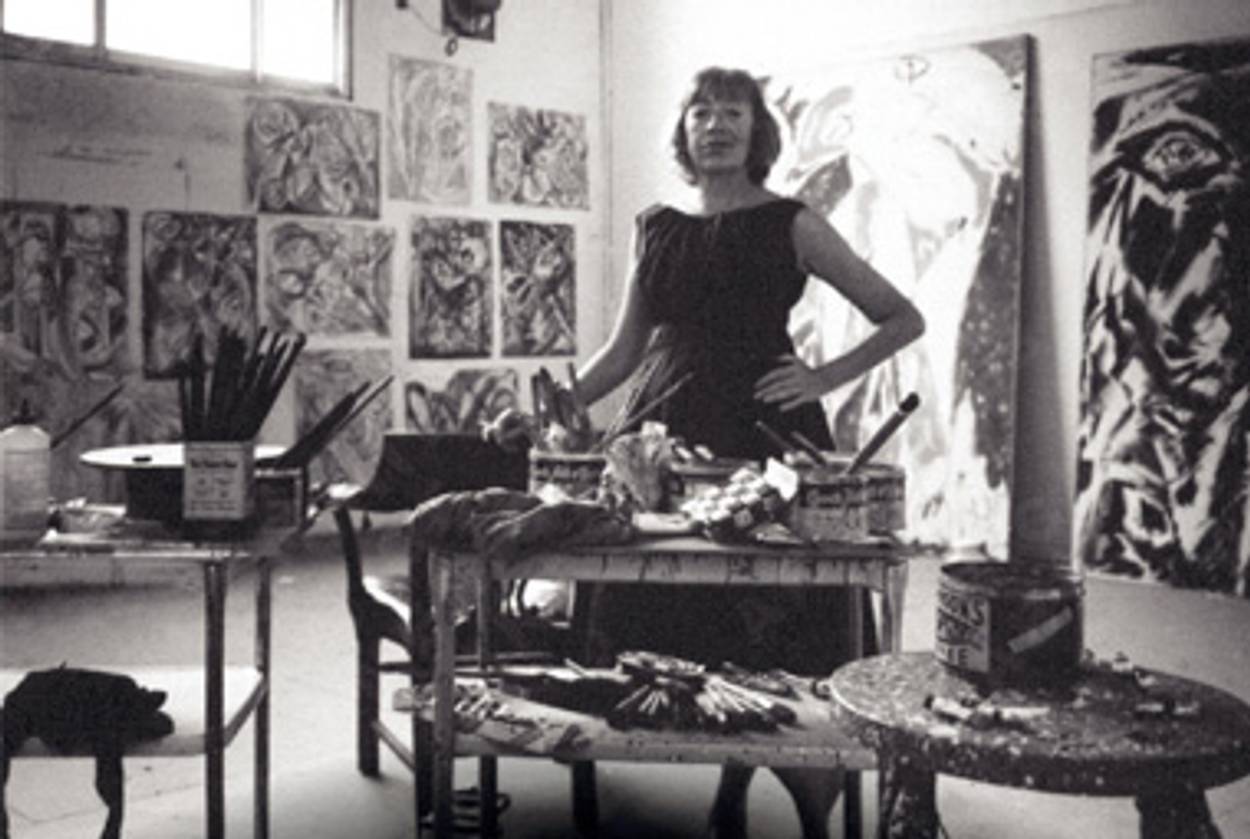

Her Own Light

A new biography tries to untangle painter Lee Krasner from the husband whose outsize personality and paint-splattered canvasses left her in the shadows

In 1943, Peggy Guggenheim came to visit Jackson Pollock’s studio on East 8th Street in Greenwich Village. In the small, poor, ferociously competitive world of downtown artists, a visit from Guggenheim was like a visit from Santa Claus: If this rich and trendsetting collector decided to feature an artist at her famous midtown gallery, Art of This Century, his reputation was made. And Pollock needed all the help he could get. At the time, he was enjoying a very different kind of patronage from Peggy’s uncle, Solomon Guggenheim, founder of the museum then known as the Museum of Non-Objective Art, and now called simply the Guggenheim. For months, he had been working as the museum’s janitor.

When Peggy Guggenheim descended on Pollock’s studio, however, the artist wasn’t at home. He arrived late, to find Guggenheim storming out the door. “I came into the place, the doors were open, and I see a lot of paintings, L.K., L.K. I didn’t come to look at L.K.’s paintings. Who is L.K.?” she demanded.

This little episode tells you all you need to know about the pathos of Lee Krasner’s life, and of the new biography Lee Krasner by Gail Levin (William Morrow, $30). Krasner was, of course, the L.K. whose paintings shared space with Pollock’s. The two painters had met in late 1941, and would be married in 1945. Guggenheim, Krasner insisted, “damn well knew … who L.K. was.” She just had no interest in Krasner’s paintings, certainly not when Pollock’s were on view. And while few people were as defiantly nasty to Krasner as Guggenheim, almost everyone in the mid-century art world agreed that Krasner’s main value was as the guardian, gatekeeper, and promoter of Pollock’s work. To this day, far more people can identify Krasner as Pollock’s widow—or as the character Marcia Gay Harden played in the movie Pollock—than can name one of her canvases.

Levin, an art historian who teaches at CUNY, has written this biography partly in order to rectify this injustice. Levin was one of a group of young feminist curators and art historians who helped bring new attention to Krasner’s work in the 1970s. Krasner was grateful for their interest, and for feminism as a political movement: “I’m glad I’m alive, now that women’s lib has brought a new consciousness,” she said in 1973. “Thank you, women’s lib.”

Yet as Levin shows, Krasner also remained wary of the idea of feminist art. One of the constant themes of her career was her rejection of all parochial labels. She refused even to call herself an American artist, seeing art as a universal and timeless pursuit, and she did not like the idea of viewers finding something essentially female in her abstract-expressionist canvases. In 1974, for instance, a group of students in a feminist art program wrote to Krasner asking her to compose a “Letter to a Young Woman Artist.” In her reply, she conspicuously avoided any mention of gender, preferring to address the “relation to past, present and future” in her work.

In her stern universalism, both political and aesthetic, Krasner was a typical member of her generation of New York Jewish artists and intellectuals. She was born in 1908 in Brownsville, the Brooklyn slum neighborhood that was a center of immigrant Jewish life. (It’s easy to imagine her crossing paths with the young Alfred Kazin, whose classic memoir A Walker in the City tells of a Brownsville boy’s yearning for beauty and culture.) Her given name was Lena Krassner, which she changed as a teenager to the more Anglicized and poetic “Lenore”; not until she was 40 did she consistently call herself Lee Krasner.

Levin astutely notes that, as the first American-born member of her family—she was born exactly nine months and two weeks after her mother joined her father in New York—Krasner would have been set apart in several ways. Unlike her parents and older siblings, she couldn’t speak Russian or Yiddish. She remembered learning the Hebrew alphabet, but she always had trouble with languages—Levin suggests that she might have been dyslexic—and it seems that the shape of the letters meant much more to her than their meaning: “Visually I loved it. I didn’t know what it meant.” Perhaps this early memory fuelled Krasner’s 1960s paintings like Kufic and Uncial, whose titles refer to kinds of script.

As a young girl, Krasner recalled, she was drawn to Jewish practice: “I went to services at the synagogue, partly because it was expected of me. But there must have been something beyond, because I wasn’t forced to go, and my younger sister did not.” But she rebelled against the segregation of men and women in synagogue and was “shatter[ed]” when she understood that, in the morning prayer service, men give thanks for being made in God’s image, while women give thanks for being created “as You saw fit.”

As she got older, art replaced religion as the focus of Krasner’s spiritual life. She herself couldn’t explain how a girl from a poor immigrant family, who never saw the inside of a museum, conceived the desire to be an artist: “I don’t know where the word A-R-T came from; but by the time I was thirteen, I knew I wanted to be a painter.” Her parents did not so much support her as refrain from causing problems—mainly because they were too busy making a living to take much interest in her plans. Krasner enrolled in a girls’ high school, Washington Irving, whose vocational curriculum included classes in the arts, and then studied at a series of art schools—Cooper Union, the Art Students’ League, and the National Academy of Design.

By the 1930s, Levin shows, Krasner was part of a tightly knit community of downtown artists who idolized the School of Paris and were committed to abstract painting. This made them marginal in the American art world, and many, including Krasner, survived the Depression thanks to the WPA, painting murals in high schools and post offices. Inevitably, Krasner became politicized during the radical ’30s, joining the Communist-dominated Artists Union and taking part in protests. These often ended in mass arrests, and the artists amused themselves by giving fake names to the cops—Cézanne, Michelangelo, Rubens. Even here, Levin nicely observes, Krasner was confronted with the scarcity of women in art history: “I didn’t have a big selection, you know, it was either Rosa Bonheur or Mary Cassatt.”

Yet Krasner, like most of the “advanced” New York intellectuals, found that her artistic ideals made it impossible for her to be a good Communist. She identified with the Trotskyites, whose opposition to Stalin made them anathema to the Communist Party. But she does not seem to have been essentially political, even at the height of her activism. The debates at Village artists’ hangouts like the Jumble Shop and Café Society concerned Matisse and Picasso, not Marx and Lenin.

As the fashion in American art began to change in the 1940s, Krasner’s colleagues—Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky, Robert Motherwell, and of course Jackson Pollock—started to win fame. Thanks to the advocacy of critics like Clement Greenberg and Harold Rosenberg, both of whom were associated with Partisan Review, these disparate painters took on a media-friendly identity as a school, the abstract expressionists or action painters. In the postwar world, the shift of the center of artistic gravity from Paris to New York was one hallmark of the “American Century,” and some surprisingly powerful American institutions—from the Luce magazines to the State Department—started to lavish attention on their work.

But never on Krasner. The contrast between her obscurity and Pollock’s worldwide fame was especially striking. In 1949, Life ran a feature with the headline “Jackson Pollock: Is He the Greatest Living Painter in the United States?” Meanwhile, Krasner was one of 17 artists in a group show in a small East Hampton gallery, where her work received one sentence in a New York Times review: “Lee Krasner’s rigidly patterned abstracts sound a call to order.” A New Yorker piece on the couple described her as “a slim auburn-haired young woman [in fact, she was 41] who is also an artist,” and showed her “bent over a hot stove, making currant jelly.” Levin demonstrates that this kind of sexism, which now seems appallingly blatant, was standard practice in the macho art world. The bohemians of East Hampton were no more enlightened than the executives and suburbanites of Mad Men.

As Pollock’s alcoholism and self-destructive behavior spiraled out of control, Krasner was reduced to the ungrateful role of caretaker. Trying to keep him working and sober, she seemed to his friends like a spoilsport or a tyrant; she had to put up with his flaunted infidelities and violent rages. Even after his death, Krasner lived in Pollock’s shadow. As Levin shows, more than one gallerist and dealer feigned interest in her paintings when their real objective was the big prize, Pollock’s estate. It wasn’t until the last decade of her life that a new generation of feminist artists and scholars began to give Krasner’s work sustained critical support.

Yet Levin never quite gives that work the close attention that would be needed to argue that Krasner was, indeed, a great artist. Over a 50-year career, her paintings varied dramatically in quality and originality. She had a very long apprenticeship, and at different stages her work seems excessively indebted to Matisse, Picasso, Mondrian, and Pollock himself. In the end, her greatest appeal to posterity may not be as a painter, or as the wife of Jackson Pollock, but—in the words of the art historian Barbara Rose—as “a beacon of integrity. She had an absolute inability to compromise with anything.”

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.