Introduction

When I was young, I believed the myth. Great artists emerged from mystic origins, fates ordained, their holy revelations divined from the nearest Delphi within driving distance. Inspiration was a concatenation of lawless voltage, ordained genius, and lysergic experiment. History unfolded in a series of rational acts; the rightful winners were obvious. Graciously, Herbert Gold never held these delusions against me.

I imagine Herb—as I know him off the printed page—would wisely recoil at being called “legendary,” a trite and cheap shorthand in this 280-character world. But little in the English lexicon can accurately describe the 97-year-old author whose offhand anecdotes deserve their own separate place in the canon. It’s not a matter of where to begin, but when to stop. Gold grew up in the suburban Cleveland of the Father Coughlin years, hitchhiked around America before Kerouac (a later nemesis), studied at Columbia and befriended Allen Ginsberg, and was nearly seduced by Anaïs Nin as a teenager. There was the stint working in intelligence during the war, the years that followed on a Fulbright in Paris, where James Baldwin lived next door and stole Pall Malls from his ex-wife, where Saul Bellow offered a crucial endorsement that set his literary career in motion. That night that William S. Burroughs was so aggrieved that Gold dared to bring his wife to a dinner party that he pissed in the sink in plain view, almost souring the lettuce.

Friday afternoon festivities at George Plimpton’s house where Norman Mailer took Gold out on a balcony and tried to fight him for mockingly blowing a kiss in his direction. The literary gala where an aged but still sleazy Henry Miller grabbed the décolletage of a starlet, then crowed “she’ll talk about it forever.” Apparently, she did. He brought Tom Wolfe to the Acid Test, and was repaid by the man in the white suit describing his “aftershave smile.” No less than Vladimir Nabokov recruited Gold as his replacement at Cornell following the success of Lolita. The old master included him alongside John Updike, J.D. Salinger, and John Cheever, on his “A-list of stories.” The example came from Gold’s Death in Miami Beach. The phrases steal the oxygen every time I see them: “Barbados turtles, as large as children,” “crucified like thieves,” “the tough leather of their skin does not disguise their present helplessness and pain.”

About a decade and a half ago, I became close with his son, a very gifted songwriter named Ethan, who introduced me to his father over lunch at a Caribbean restaurant. For an hour I peppered the elder Gold with embarrassing questions about whether Allen Ginsberg could walk on the Galilee and if Kerouac could turn wine into more wine. With great patience and restraint, Gold made me realize that even the best writers are just regular people with extraordinary talent. It was a reassuring point of inspiration. By coming in contact with a genuine artist, I understood that the fables were far less interesting than what you leave on the page.

My admiration for Gold runs deep. Of course, he has created an extraordinary body of work. Over two dozen novels, essay collections, memoirs, and even a poetry chapbook. The California writing assembled in A Walk on the West Side: California on the Brink holds its own with Didion’s; Haiti: Best Nightmare on Earth is a spellbinding history of the island’s startling magic, psychedelic traditions, and desecration at the hands of the Duvaliers. My Last Two Thousand Years is a riveting megillah of his search for his faith, as he traces his tribal roots across three continents. Fathers, the 1966 “novel in the form of a memoir” that made him famous, somehow explains the complications of my own paternal relationship better than anything else I’ve read, while 2008’s Still Alive!: A Temporary Condition ranks alongside the great meditations on death and the cold-blooded treasons of aging.

But the most profound wellspring of my respect stems from his compassion and fundamentally mortal qualities: those humble truths, not the gilded folklore. I’ve witnessed a sacred devotion to his sons, daughters, and grandchildren. I’ve been lucky to sip coffee and soak up sage wisdom at his rent-controlled apartment on Russian Hill, blessed with a million-dollar view of San Francisco Bay. His living example and literary output serve as a North Star, a still-breathing connection to a glorious and vanished past, and a reminder of a tradition that must endure.

This story that you are about to read reflects Gold’s menschlike generosity. Last month, it landed on my doorstep, (and by doorstep, I mean voicemail), when a stranger named Ray March called to ask for help in getting it published. At some point last year, March, a former journalist-turned-publicist-turned-journalist once again, became struck by the need to atone for an anti-Semitic slight made to Gold during a Pebble Beach tennis tournament in the Summer of Love. Somehow, it morphed into the tale of the withering prejudice that Gold faced during his adolescence and the recurring bigotry that followed; it’s about an unlikely bond forged by two writers late in life, and the ever-encroaching darkness of the end. —Jeff Weiss.

Where would I begin in expressing my regret for another man’s prejudice to a man I didn’t know?

I was in search of Herbert Gold. Not only had I never met him, I had never read any of his many novels. Never read Fathers, his early classic, or Still Alive!, his later-in-life memoir.

I knew nothing about Gold except by an act of anti-Semitism 50 years ago when I learned he was Jewish. Brought up in a home that fringed on indelible Catholicism, I had no idea what it meant to be Jewish in America. But I instinctively understood something was wrong five decades ago when I was confronted with a wordless act of prejudice aimed directly at Gold. That singular moment never left me.

In 1964, after reporting for a midsize daily in the States and an investigative watchdog weekly covering U.S. troops in Germany, I came back from Europe because my wife was three months pregnant. We had no hospital and she said her doctor was anti-American. I took a position as lead reporter assigned to covering county government for a newspaper near my hometown. I was 30. But my aggressive reporting didn’t meet the publisher’s idea of objective news coverage. Cease writing stories exposing a local politician, they said. I resisted. I was told a second time. Pay increases became infrequent. The message: The newspaper was a Chamber of Commerce sheet. I carried a guilty conscience for not providing a better style of life for my wife, who emigrated when she was a teenager to the U.S. from Germany with her parents. I believed that life as the wife of a grind-it-out, low-paid reporter was not what she had in mind. I’d always chased the story, not the career. The job was going nowhere. A colleague and I joked that we needed action, a war for motivation. Something was missing. I was a victim of pursuing an idea, on the brink of a midlife career crisis. I took an attractive-paying position as the publicity manager at Pebble Beach. It wasn’t a war, but the money and a larger house would have to substitute. I thought I could find what was missing when I went to work for S.F.B. Morse—Yale class of 1908, Republican, racist.

Fifty years later, I found an address and tracked down Gold’s telephone number in San Francisco. I called and introduced myself. I explained I was a journalist, a writer. I strung some disjointed words together and told him I wanted to make an apology. Was this a good time to talk? He said it was.

Awkwardly, I told Gold the story of when in 1967— the Summer of Love in San Francisco—he was scratched from playing in a celebrity tennis tournament at Pebble Beach because he was Jewish. I explained to Gold the idea of a celebrity tennis tournament fit in nicely with other special events such as the original Bing Crosby Clambake and the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance. The plan was to invite amateur tennis players from San Francisco, 125 miles to the north, and a few movie and TV stars jetting up from Hollywood. The Bay Area’s social and corporate elite had been reliable carriage trade since 1880, when Charles Crocker’s Southern Pacific carried them to the Hotel Del Monte, ancestor to Morse’s Lodge at Pebble Beach. There would be champagne partying, gourmet dining, and mingling with members of the Beach & Tennis Club. What I didn’t say was that, just like the more famous special events at Pebble Beach, it was a skillful land marketing operation.

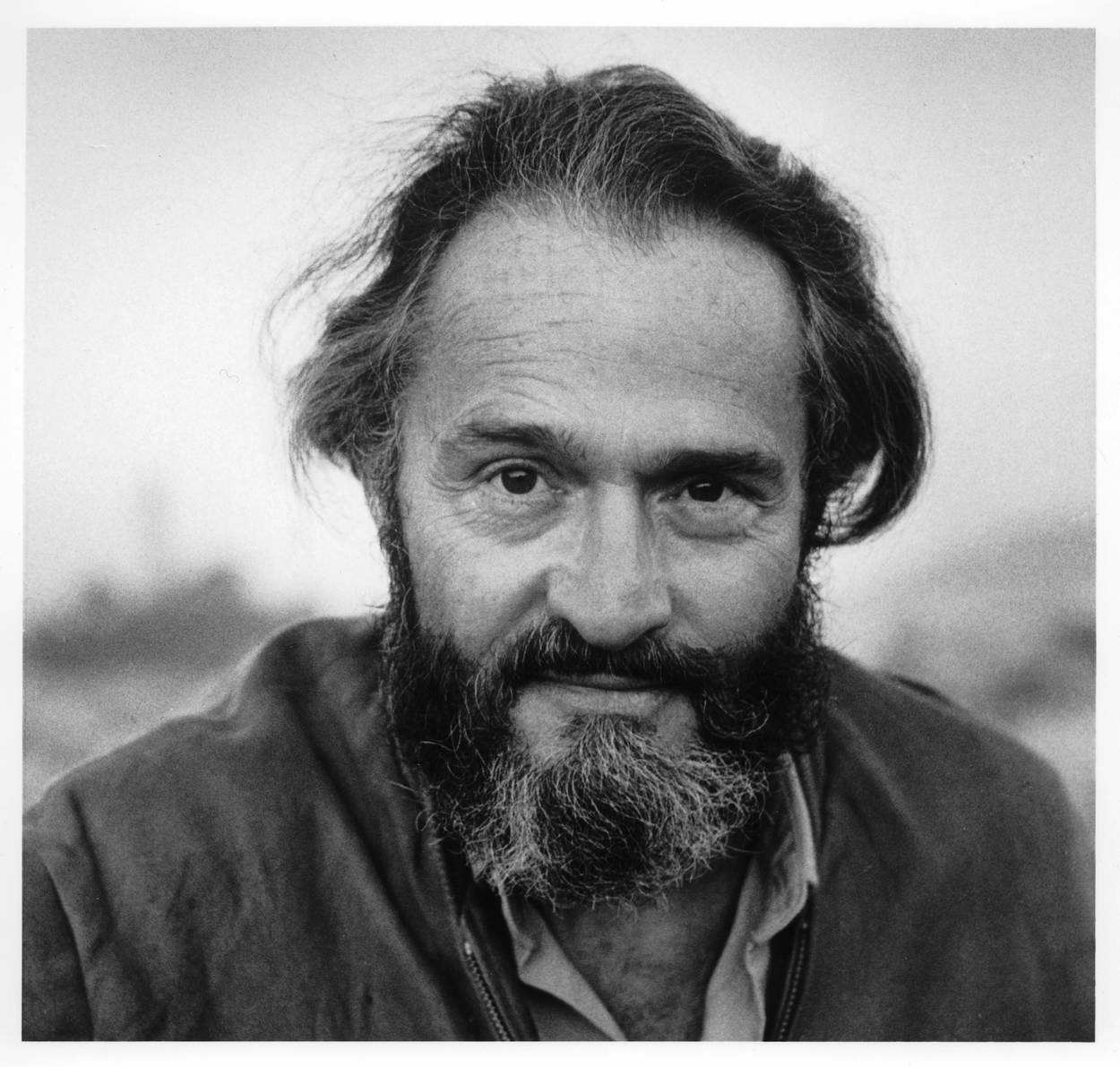

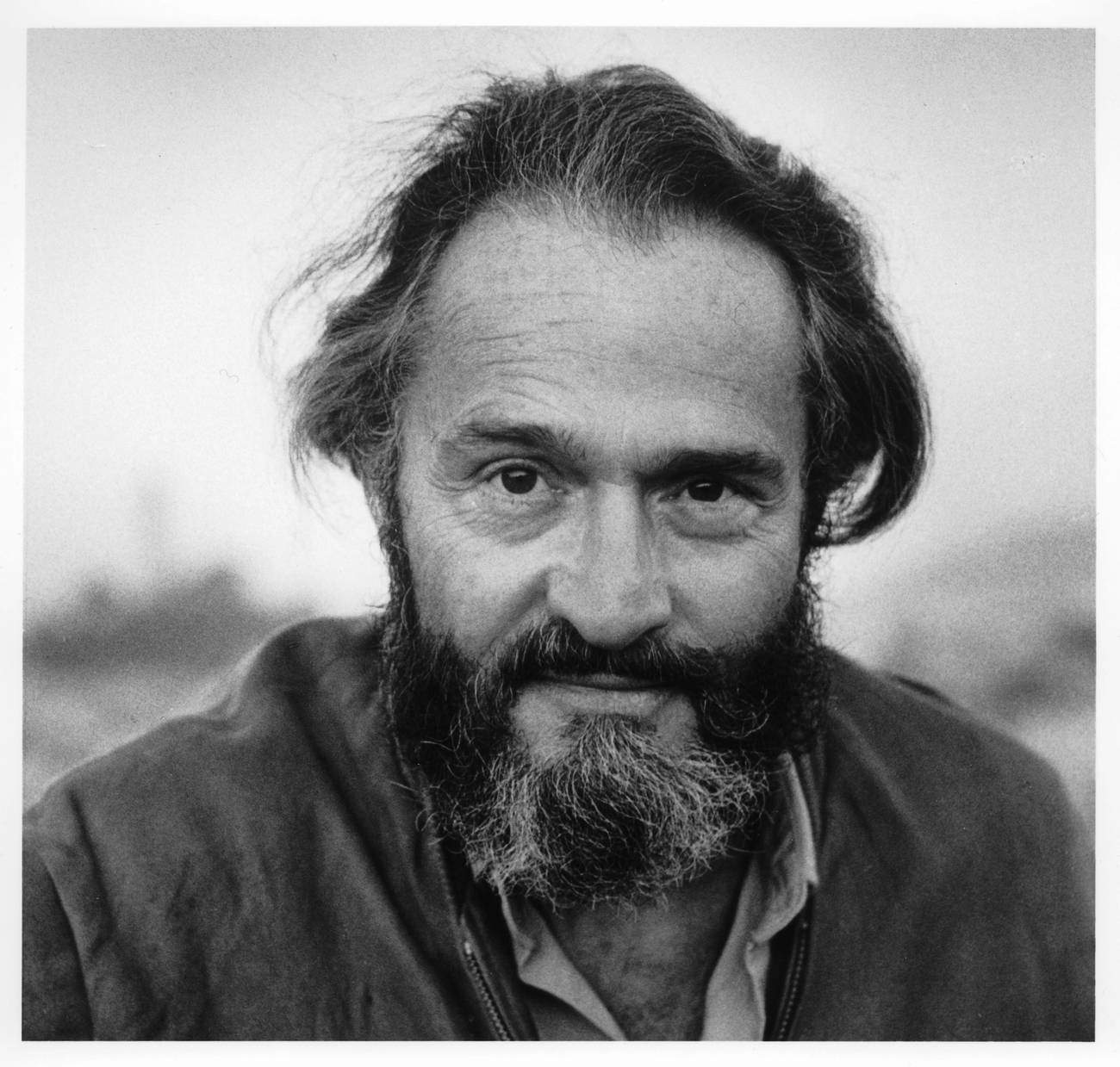

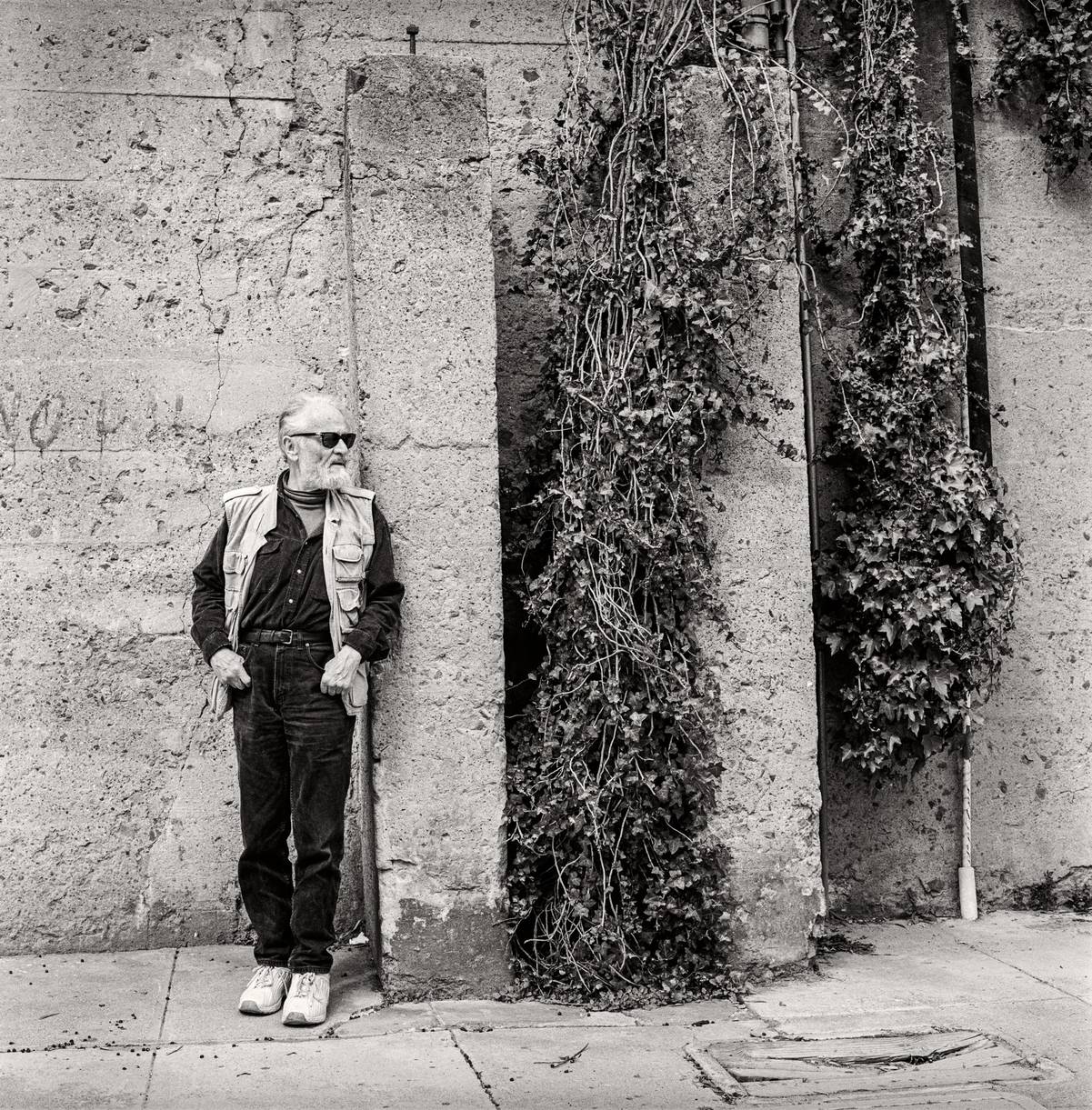

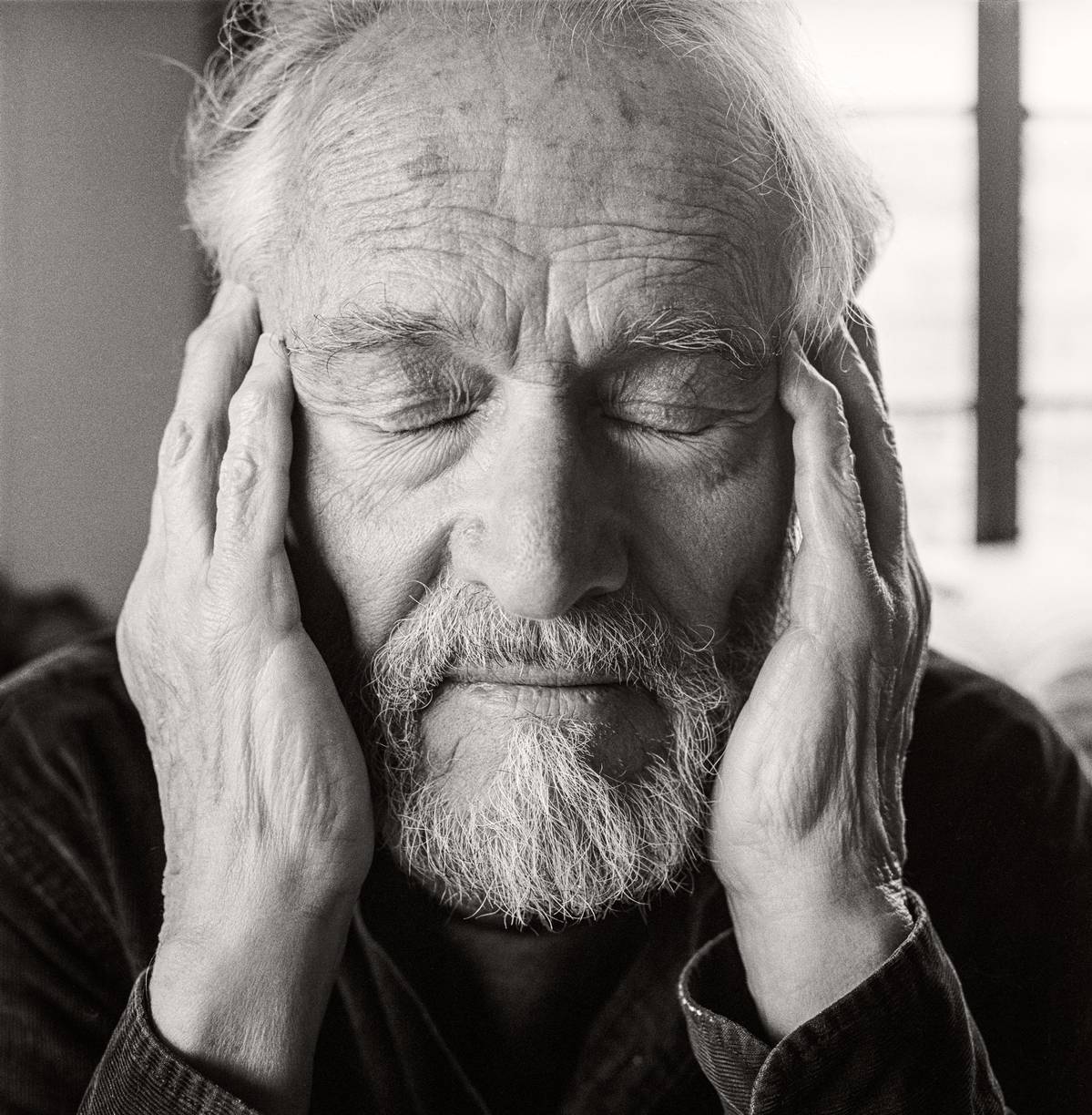

Herbert Gold, 2005© Thomas Kern

I recommended Gold because he was San Francisco’s most celebrated novelist and he frequently appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle’s Herb Caen column. Caen was also on the invitation list. He, too, was Jewish, which I did not know, and it didn’t occur to me that I should care.

I explained to Gold that when the list was pared down to final choices, both he and Caen made the cut, but when I showed the list to my boss, the company’s advertising and public relations director, she raised an eyebrow and looked toward Morse’s adjoining executive offices. I took her to mean: Morse didn’t like Jews, didn’t I know that? Yes, I knew, but I had no way of recognizing a Jew from a Catholic or a Methodist. I’d forgotten an incident when I was in high school and my parents drove through the private tollgate to Pebble Beach for a special dinner at The Lodge. Instantly, they were back and my stepfather was raging. He had been refused a table because they thought he was a Jew. Now, time was running out on Morse’s deed restrictions prohibiting Asians, Africans, Arabs, and Jews from building or living in his private domain. No words were spoken between my boss and me, but I understood the message of her raised eyebrow. Herbert Gold, the Jewish novelist, was scratched. Herb Caen, the Jewish newspaper columnist, made the cut. S.F.B. Morse had his preferences when it came to his prejudices.

Gold was entitled to an apology from me for being a silent witness to Morse’s anti-Semitism. I felt a mental prodding over the passing decades to apologize for Morse’s prejudice, to make it right for Herbert Gold, a man I’d never met. I was complicit in submitting to Morse’s bigotry. To reconcile my role, to cleanse the guilt, there had to be a reckoning. I was apologizing to Herb Gold and to myself because there was nothing else I could do, but deeper I was apologizing to myself for not responsibly fulfilling a career that lived up to my potential.

Gold didn’t remember a celebrity tennis event in 1967. He didn’t even know where Pebble Beach was, but after arriving in San Francisco he became what he sarcastically called a “celebrity” and frequently appeared in Caen’s column. Caen wasn’t a bad player, he said, but not great. “He was an odd duck. Caen didn’t want to be known as a Jew. He squirmed with the idea of being Jewish.”

Gold played at Golden Gate Park’s public courts and also at the private California Tennis Club. He wasn’t a member of the Cal Club, but that wasn’t a problem. He had been invited to join, but he and his wife, Melissa Dilworth, lived on Lombard at the crooked section and there were courts nearby. His answers came slowly, thoughtfully, softly. He was certain he had never been to Pebble Beach.

“What was his name again?”

No, he didn’t think he had ever met Morse, couldn’t place the name. There was a silence. He knew another Morse. The conversation went on, and then.

“Yes.” The name was beginning to surface.

“Oh, yes. A realtor, wasn’t he?”

“You’re making an apology for Morse?”

“You don’t need to do that.”

He said he did know a Haitian Richard Morse, son of white professor Richard Morse Sr. and a Haitian mother and therefore part African. We talked a bit more.

“I’m 96. How old are you?” he asked.

“Why, you’re just out of knee pants!”

Relief. It was over; the awkwardness vanished. It was something that had to be said. I felt cleansed but exposed, as if I had laid bare my darkest secret. Gold understood.

“You should write about this,” he said.

I wrote Gold a letter asking general questions about his life as a Jew in America. He telephoned; he doesn’t use a computer. There were no email exchanges, no iPhone, no caller ID, and no tape recordings. Direct dial, all freehand. A novelist and a journalist conducting their professions the old way, but letters worked. Gold didn’t hear well. At the beginning of one call he said, “Speak as if you were writing. Pause between words.” His instruction was an unexpected metaphor. A rhythm developed. I slowed down, and in his smooth cadence, he answered. Sometimes he’d go back to a thought, expanding a story with great clarity.

I said I wanted him to read the final draft in order to catch any errors in fact, but what I really wanted was his approval of my writing. It was mid-summer, 2020. We talked during the COVID-19 crisis, Trump. “Trump would be an anti-Semite if he didn’t have a Jewish son-in-law and a convert Jewish daughter,” Gold said.

If Gold weren’t Jewish, I thought he could be a Jesuit priest, at least one I might like, trained in the classics, quick sardonic wit. Maybe one with a pre-priesthood innocence of passing carnal knowledge. One who could relate. Not the game-playing Dominican nuns at Saint Catherine’s Academy when I was a slow-reading second grader, or the diocesan priest who raged through the sacristy after I nearly fainted under the incense and walked off the altar during Wednesday evening benediction when I was in the sixth grade. Those memories shadow me. The nun who read my mother’s handwritten postcards to me because I couldn’t read cursive that isolated year my mother left me at the Catholic boarding school. The same benignly smiling nun who never varied in my mother’s message: “Be sure to mind the nuns.” And, I never looked back after that Wednesday benediction when I fled the sanctuary floor where Franciscan Father Junipero Serra was buried. I thought I was going to faint in the haze of frankincense and myrrh. I had violated the sanctity of Serra’s resting place. The priest screamed at me. His ankle-length vestments, black cassock, and white surplice flew like magpies at his heels. How could I be so sacrilegious? Swish. I was unredeemable. Swish. Banished from the duties of altar boy for life. Swish. Years passed. Pope John Paul II, rationalizing Fr. Serra’s vast California mission expansion in God’s name, beatified the Franciscan. No one mentioned how many Indians gave their lives in the name of religious land development, but hundreds of protesters stood at unmarked graves in the side yard shadow of the mission where I had fallen from grace.

“I’m not a practicing Jew,” Gold remarked. “I call myself a Chinese Jew because the Chinese Jew worships his ancestors, but I always say I am a Jew because I am. Sartre said, ‘You become what you are.’” It was as simple as that.

In remembering schoolmates, army buddies, and friends, he said most of them had old-aged into the ground. He told me about growing up in Lakewood, Ohio, a suburb of Cleveland in the 1930s. As a 10-year-old, his schooling coincided with the rise of Adolf Hitler and the Third Reich. German concentration camps were filling up with Hitler’s political opponents and German Jews were forced to live under rules restricting their public and private lives. German university students burned books they believed held foreign influence, especially Jewish literature. In the United States it was a time of isolation. As Hitler was conquering much of Europe, the United States was vacillating on entering the war and opportunistic pro-Nazis took advantage of the country’s inaction.

It was time to read Herbert Gold the novelist. I ordered two of his books: Fathers and Still Alive!. In my anxiety I ordered two copies of Still Alive!, so I followed up with another order of Fathers, unknowing that my wife, Barbara, had also ordered a copy for me. I had two of each, so I gave the extras to a friend. What arrived between the pages of the first used copy of Fathers was a startling discovery. I wrote Herb a letter describing my findings:

Two more of your works arrived in the mail today, actually only one because I apparently ordered two of Still Alive. There’s probably some significant meaning to it. But, what’s amazing, especially if you believe in serendipity, is what arrived in the other book, Fathers. I was thumbing through the pages; back to front, when under the front flyleaf taped with a Band-Aid to the inside hardbound cover was a U.S. half dollar coin! The year on the coin is 1967, the same year the beginning of my story about you takes place. There is also a previous owner’s name. I suppose I’ll recover, but until I do I think I’m going to let the half dollar “ride.”

The work on your piece goes on, a bit slow because I am experimenting with form. At least it is a departure from my usual journalistic writing.

May this find you well, Ray

Herb called a few days later and we laughed and wondered if there was a message under the Band-Aid, but we decided we’d never know and that was it. He offered to split the 50 cents with me, but it’s still in my possession.

I thought about our aging, a subject both of us considered a distraction, an unnecessary subject to dwell on, but I did not want to take for granted that either of us would live forever.

Far-right, pro-Hitler bands were common when Gold was a young student. He said there were the Black Legion night riders in Jackson, Michigan, a three-hour drive from Lakewood, and in the South there was the white-hooded KKK. And then there were the Silver Shirts, led by William Dudley Pelley. Their anthem was the Battle Hymn of the Republic. The far-right Silver Shirts’ colors were different, Gold explained, because they saw themselves fighting the war on an all-American front. Bundles of Silver Shirts newspapers were regularly dropped off at Gold’s junior high school.

“I picked up my copies of the Silver Shirt newspaper at Taft … it informed me that President Roosevelt’s real name was Rosenfelt. It was at Taft that the kids called me a Christ killer and chased me home.”

(Still Alive! is in reprint as the original working title, although the publisher wanted Not Dead Yet. Gold said he settled on a compromise. After his death, the title of the book could be changed to OK, Finally.)

He told me about the German-American Bund, whose membership was exclusive to Americans of German descent, and its student exchange program. Lakewood Emerson junior high students went to Germany and kids from Hitler’s Germany came to Lakewood.

“One Lakewood student returned from Germany and spoke at a student assembly,” Gold said. “He was asked if there was a problem with Jews in Germany and he said no, there wasn’t. Then he was asked if he saw any Jews and he said no, he had not. And they all laughed. I felt as if there were a thousand kids in the auditorium all looking at me. There were only a couple of Jewish families in Lakewood and everyone knew who they were. A school friend who was not known by classmates as a Jew whispered to me, ‘I’m Jewish, too.’ Once when I was playing tennis at Lakewood Park, I heard a player on the next court say, ‘Jews again, Jews again,’ but then I realized he was actually saying, ‘Deuce again, deuce again.’ I was a bit paranoid. Have you seen ‘Night and Fog’? You should.”

I thought about the privilege I was naturally born with and took for granted. I joked about being blond and blue-eyed, Danish on my paternal grandfather’s side and Austrian on my maternal grandmother’s side. It was just the way it was, but my bragging, I can see now, was a thrust and parry, an offensive maneuver of superiority. The grandson of European emigrants, I once declared during a playground recess, “When I grow up, I am going to vote for Roosevelt.” That, too, made me feel good and special.

As Gold and I continued our talks, I thought my Catholicism didn’t have much to do with anything. The story was about Gold. Our religions were a coincidence, but with each rewrite and Gold’s urging me to pull more threads through the loom he encouraged me to look closer at myself and what I was bringing to the story that day I called to apologize. I always referred to our work as a joint effort and he said no it was mine, not his. And there, lurking in the pages of Gold’s stories, was Father Coughlin, the priest from my past.

In Still Alive!, Gold writes,

From the Shrine of the Little Flower in Royal Oak, Michigan, Father Coughlin broadcast his anathemas in a resonant tenor, which echoed from most of the radios up and down Hathaway Avenue on Sunday mornings.

“Mother,” I asked, “what’s a shrine?”

“Who shrine? What farkokteh shrine?”

“Shrine of the Little Flower.”

“Don’t you have better things than why are you asking dumb questions?”

I began to read Fathers, in which he wrote of his junior high romance with Pattie Donahue, whose father hated him because he was Jewish. Gold explained that kids could be rebellious by being friends with someone Jewish.

Appraising me with her turtle-round eyes, shrewd to calculate the value of an investment, she first created a bear market by sighing, Ohh, rustling her dress, and accidentally touching my arm with her transparent turquoise-veined hands. Cologned and dusted with powder, she breathed on me.

“Yes?” I spilled out, naked in summer smells. “Do you like me, Pattie? I like you.”

In Lakewood, Gold lived in a Catholic neighborhood. It was there a girl kissed him for the first time, but it wasn’t Patti.

“Being Jewish worked out well with the Catholic rule of no premarital sex, which was also the advice of the rabbi,” Gold laughed. “From our point of view, Catholics faced dire punishment if they broke the rule of no premarital sex because the Jews had the devil in them. But adolescent hormones will have their way. The result was that I was popular with the girls. I had my first kiss at this time. Her name was Donna Smith. She lived in an apartment building and we were going up in the elevator when she turned off the light and kissed me. It was sort of a brushing.”

In high school, he was editor of the Lakewood High Times. His teacher was Seymour Slater, who recommended Gold for a scholarship to Columbia. The application included a story Gold wrote about a boy and the subject of suicide. Gold didn’t think his character in the story was suicidal, but the admissions dean at Columbia was worried Gold might be a problem.

Herbert Gold, 2005© Thomas Kern

“He asked me about the short story and said he was going to show it to the philosophy professor who would be one of my instructors. ‘Is this guy going to be a menace to other people?’ The professor assured the dean I was going to be OK.” The work was just that of a young inquisitive boy. It was Slater who told Gold he got the scholarship.

“I took the Greyhound Bus to Columbia and later earned a master’s degree. I was a survivor of Cleveland suburbs. When I wrote Therefore be Bold, I dedicated it to Seymour Slater. It’s a description of what Sophocles said to Oedipus.”

Gold left Columbia in 1943 to join the Army Air Corps with his buddy Marvin Shapiro.

“We were going to be fighter pilots and kill Nazis,” he said, “but because of my poor eyesight I was transferred to military intelligence in the Army and studied Russian. I could take an M-1 rifle apart in Russian.”

The skinny city Jew, wearing glasses, knowing too much from books, spilled head over heels into an infantry company—this is an old story. In the movies it precedes on ritual lines, with a folk song fresh from the factory and a conclusion in general brotherhood (soft-focus fadeout.)

During basic training at Fort Bragg, Gold said he was nearly court-martialed. As his story unfolded, I was taken back to 1953. I’m a senior in high school rooting for Montgomery Clift’s Prewitt in his revenge fight against Ernest Borgnine’s Fatso in a scene in From Here to Eternity. The film was directed by Fred Zinnemann, an immigrant whose parents were Austrian Jews.

“We were marching and the guy behind me was kicking my heel and saying ‘Kike, two three four, kike two three four.’ I swung on him, and when I did, I dropped my rifle, which was a court martial offense. The captain gave me a choice of a court martial or a boxing match in the company dayroom. We flailed at each other until we could no longer move. It was all part of the war against Nazism. My friend Marvin became a fighter pilot and was shot down over Germany. He parachuted out and was killed on the ground because his dog tags had the ‘H’ for Hebrew on them.”

Gold, back from the army in 1946 and now a World War II veteran on the GI Bill, was idling his time in the admissions office at Columbia when the dean was called away. Gold’s application file was on the dean’s desk. He took a look at it. The dean had written on the application, “There are enough Jews at Columbia, and while he wouldn’t oppose Gold’s attending Columbia, he would not agree to give Gold a scholarship.” McKnight was the dean’s name, Gold remembered. Without a scholarship to support his Columbia reentry, he worked at what he called “meal” jobs.

The mere babies who were our classmates could dress in their Ivy League tweed jackets from J. Crew, their rep ties from wherever rep ties were striped; proudly we flaunted our khakis, our field jackets, and our paratroop boots if we’d been able to liberate them.

“Columbia College was a small college then. We never talked about being Jewish. Allen Ginsberg was a classmate and we became good friends. I didn’t know Heller or Salinger who were there about the same time. I did get to know Jack Kerouac who also went to Columbia and played football. He was a drunk and a bully and an anti-Semite. Much later Ginsberg went to visit Kerouac, but he wouldn’t invite Ginsberg in and he yelled, ‘No Jews in my house.’ Ginsberg never explained, but he was in love with Jack Kerouac. In San Francisco, Ginsberg and I hung out in a cafe at Columbus and Broadway.”

A well-known novelist when he arrived in San Francisco, Gold met a well-to-do woman who didn’t believe in the “Holy Coast,” as she called the Holocaust.

“I can’t say her name because she’s still alive,” he said. “To prove it never happened, she told me over dinner one night that she had met a very nice man who assured her the Holocaust never occurred. I asked who this man was, and she said, ‘Oh, he was a Saudi or Lebanese.’ I invited her to attend a showing of Night and Fog, a 1955 French documentary depicting the lives of prisoners at Auschwitz and Majdanek. It was at a North Beach theater which at that time showed art and foreign films. I said we should have dinner after the film so we could talk about it. When we left the theater, she said, ‘I just want to go home.’ A year later, I reminded her of our seeing Night and Fog and she had no memory of seeing it. She said, ‘Oh, Herb, did we see Claire’s Knee?” Gold said he lost many relatives in the Holocaust, but two cousins from Poland survived and became doctors. “I have nothing against Germans unless they look my age and then I wonder what they did. It’s not unnatural to mistrust strangers. It’s a natural phenomenon; I don’t forgive the people who treated me as they did in Lakewood.”

He asked if I had watched Night and Fog and I said I tried but I couldn’t stay with it. I’ve never been able to watch movies depicting the cruelty of Nazi Germany, the helplessness of seeing the insane inhumanity of it all, piles on piles of stacked corpses. I am appalled, infuriated with the rationale of Holocaust deniers. I am uncomfortable, self-conscious, when I hear the German accent because to my ear it’s become stereotyped by movies of the Nazi era. Gold said I should try to see the movie again. I understood his feelings, but I’m not sure I will attempt Night and Fog. Maybe he won’t ask.

I thought about our aging, a subject both of us considered a distraction, an unnecessary subject to dwell on, but I did not want to take for granted that either of us would live forever. I wasn’t at ease taking Gold’s story causally. One night before sleeping I said to myself, ‘Jesus, Ray, you’re 85.’ And I answered, ‘Jesus, Herb is 96.’ And I said, ‘It will all take care of itself.’ When I finished writing my last book—after holding to the mental pressure of a self-imposed deadline for six years—I had to give myself permission to let up. I was taking antidepressants for an anxiety disorder after narrowly avoiding a mental breakdown. It wasn’t the first time. In my 40s, I woke up one morning unable to get out of bed. Two psychiatrists and a psychologist eventually got me on my feet. My first two marriages ended in divorce. My third, to Barbara Laiolo, was an answer that couldn’t be foretold 35 years ago. Still, I worried. I worried I wasn’t successful as a journalist who took a near-fateful detour. I worried that writing books was not enough to catch up with my former colleagues, some who went on to cover wars, and were now retired. I worried about my inability to say this much about myself. My lifetime assignment was to write about others, not me. I told Gold I worried about finishing the piece before he died. In uncomfortable confessional words, I told him I was straining under a self-imposed deadline, a deadline neither of us acknowledged, and that was death. He said, “Tell a sad story of your life, and make it funny. Write your own experience, do what you feel is right. Keep running it through the loom.” Over the summer, fall, and into winter, I followed Herb’s advice. I reworked the piece, going deeper with each effort, and sent Herb the drafts. He called weekly. Together, we ran them through his loom, which I learned also meant taking some threads out. And then he reminded me of my promise to let him read the final draft.

“If I don’t like it, I’ll come back to haunt you.”

“But you won’t be able to find me!”

“Ghosts can find anybody. I’ll get a mop. I have a broom, yes. I have a broom or a vacuum cleaner.”

Gold called one afternoon. He said if I ever needed to come to the city he would find some fine brie and good coffee and he added that he wasn’t sure if he had mentioned it, but he preferred ‘Herbert’ in print, though his friends called him Herb.

“We could have lunch at an expensive North Beach restaurant with a courtyard and a fig tree,” he said. “Maybe with a beautiful young woman so it won’t seem to be so expensive.”

If a man finds it within himself to live without others, he can live walled up and quiet for a long time. But then, he may make the next discovery, or life makes it upon him—that he cannot—and he grows a rage for connection, communication, personal fact, knowledge of the company he was born to.