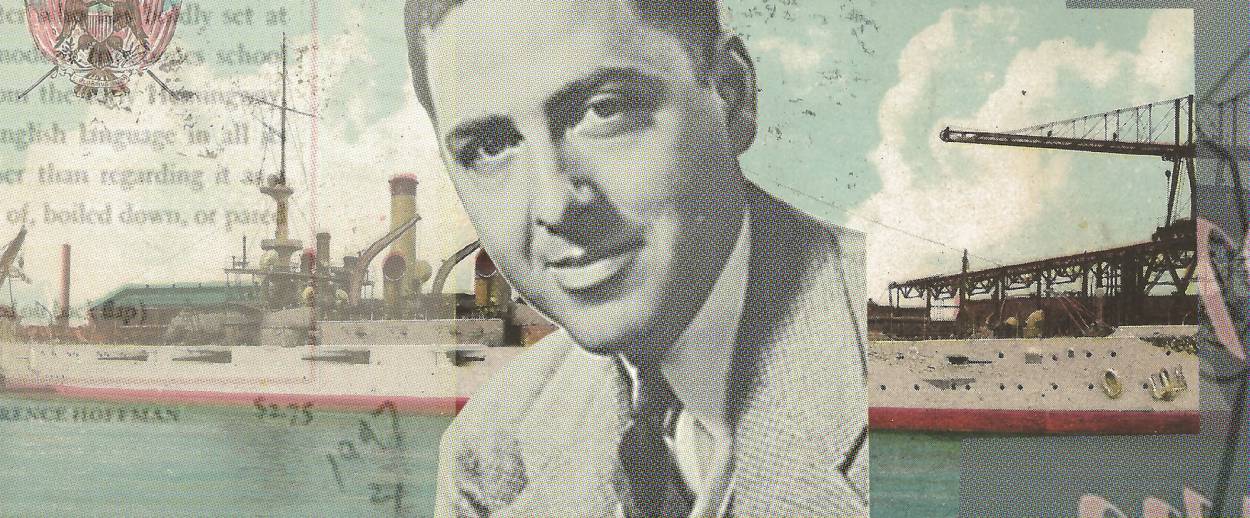

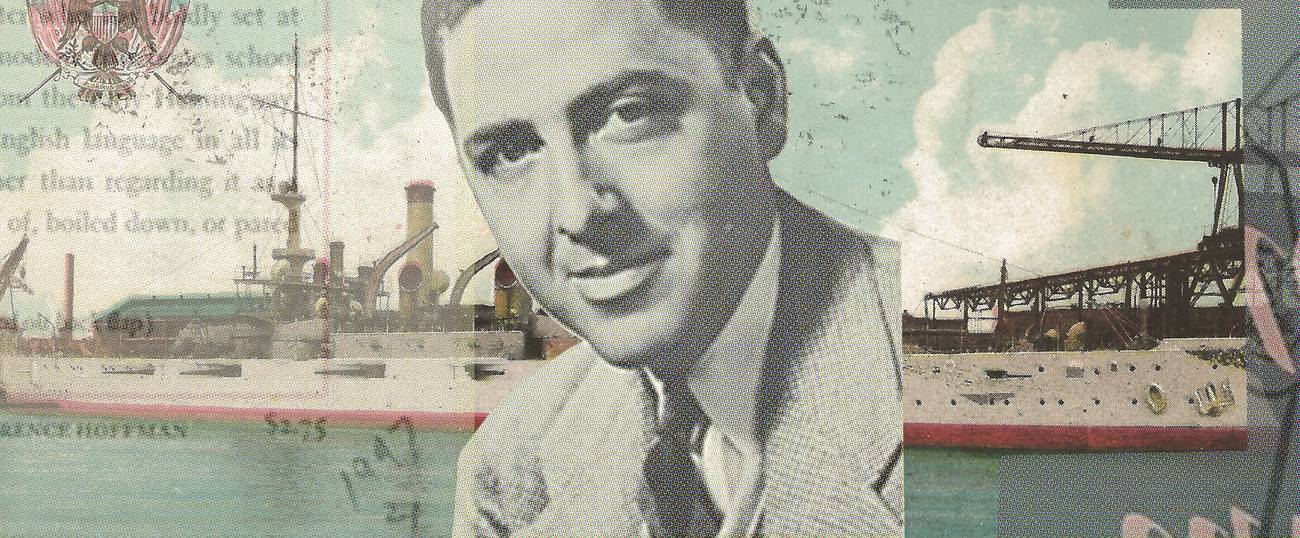

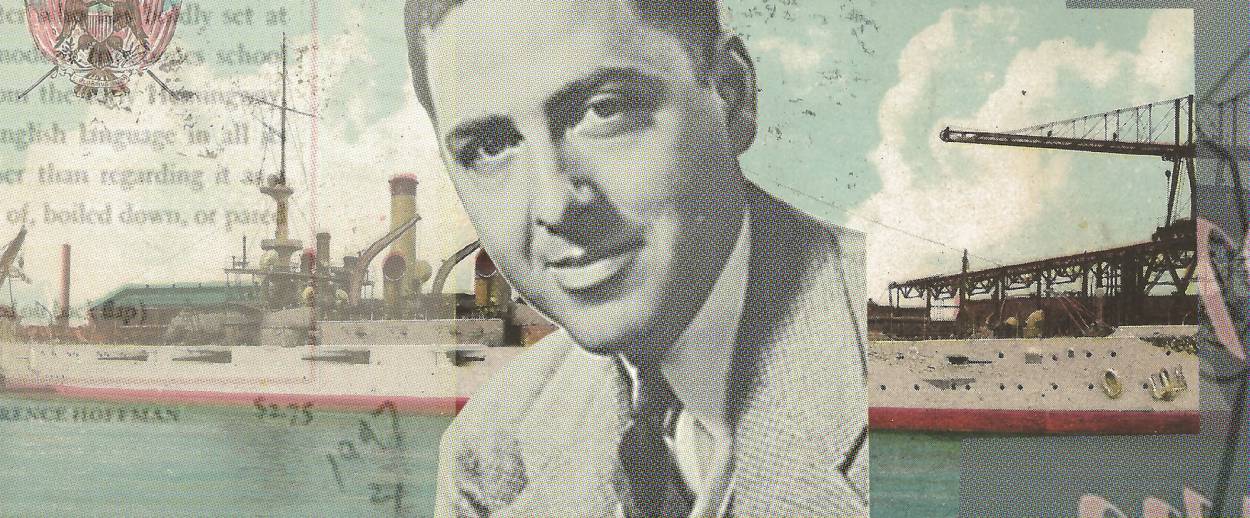

Herman Wouk, the American Jewish Writer Who Wrote Huge Best-Sellers and Wasn’t Especially Neurotic

The 100-year-old titan of American letters recalls his very happy publishing career, in the new ‘Sailor and Fiddler’

Looking back on it, the triumph of American Jewish literature in the 20th century seems like something foreordained. Take a people, Eastern European Jewry, that had always cherished literacy and give them a freedom they had never been granted before, and the result is a creative explosion—Death of a Salesman, The Adventures of Augie March, Portnoy’s Complaint, The Catcher in the Rye (not to mention the Broadway musical, Tin Pan Alley, and Hollywood). Why is it, then, that the American Jewish writers who were most successful, whom we now regard as classics, did not make success their theme? On the contrary, they generally wrote about failure, alienation, neurosis, and guilt—to the point that these subjects came to seem stereotypically Jewish in American culture. If the American Jewish story is, on balance, a very happy one, why are our books so miserable? Where are the well-adjusted Jewish writers?

The answer is that such writers did exist, but the critics who dictate literary posterity had little use for them. Just look at Herman Wouk. Bellow and Roth, for all their popularity, never dominated the best-seller lists for years at a time the way Wouk did with books both explicitly Jewish, like Marjorie Morningstar, and completely non-Jewish, like The Caine Mutiny. Indeed, the sheer number of his readers, over a span of four decades, means that Wouk did more to shape Americans’ image of Jews than any other Jewish writer. In his World War II books The Winds of War and War and Remembrance, and in his Israel books The Hope and The Glory, and above all in his best-selling primer on Judaism, This Is My God, Wouk presented a vision of Judaism at one with itself: proud of tradition, pious toward the past, devoted to Zionism, yet totally open to the American experience and all its rewards.

In his slight but charming new memoir, Sailor and Fiddler: Reflections of a 100-Year-Old Author, Wouk shows that this description of his Judaism was also a description of himself. If ever a man lived the American Dream, it was Wouk. Through the sheer power of his imagination, he became rich, famous, and beloved, while enjoying a loving marriage (just one, unlike many writers of his generation). The only tragedy he records was the accidental death of his first son, who drowned in a swimming pool at the age of 5. Wouk has never written about this experience before and alludes to it in this book in only the most restrained terms. Overall, however, Wouk was so fortunate that, when Isaiah Berlin suggested he write his memoir, his wife—“Betty Sarah Wouk, the beautiful love of my life”—discouraged him with the words, “Dear, you’re not that interesting a person.” Wouk agreed but thought that a memoir by a contented writer might be interesting simply as a contrast: “Biographies of writers were then much in fashion, confessional books by or about Jewish authors all shook up with angst. I was not one of those, and might that not be a piquant novelty?”

Happiness and introspection do not usually go together, and so it proves in Wouk’s case. Why was Wouk so at home with his Judaism, remaining an observant Jew all his life, when most American Jews of his generation fell away from strict observance? His only explanation is that his father read him Sholem Aleichem stories: “Reading Sholem Aleichem today, I hear in his warm, clear prose my father’s Friday-night voice—the lover of Jewish characters and traditions, the Zionist, the unshakable optimist, the naive American patriot who freed himself from czarist Russia.” This is misleading as a description of Sholem Aleichem, who was far from an optimist and had little use for America. But it is a telling misinterpretation, since it is colored by Wouk’s nostalgia for his Yiddish-speaking childhood. “For some of the last century’s literary elite, mostly Jewish, my books were outside their ‘canon’ of protest and alienation,” Wouk scoffs. “They were entitled. They never heard my father read Sholem Aleichem on Friday night.”

The title of Sailor and Fiddler alludes to the two institutions most important in shaping Wouk: the U.S. Navy, in which he served during WWII; and Jewish tradition, as embodied in the title of Fiddler on the Roof. (Again, leave it to the intellectuals to deride Fiddler as kitsch. Wouk, like most American Jews, sees it as a moving and authentic portrait of the Jewish past.) In This Is My God, he unites the two in an image I have always found lovely: Being Orthodox, for Wouk, is like being an officer in the Navy, the “senior service.” Jews are subjected to a lot of duties, a lot of commands and onerous routines, but these are marks of distinction and honor, which they embrace with pride. Wouk writes little in Sailor and Fiddler about Jewish observance, but he makes clear that he always kept kosher, whether on Park Avenue or on a Caribbean island. If there is a tension between Jewishness and Americanness, between rigor and opportunity, it is one that Wouk seems never to have felt. If he had, he might have become a different kind of writer altogether.

In his telling, however, becoming a writer was more a whim or accident than a calling. Wouk started his career during the Depression as a gag writer for Fred Allen on the radio. He made a good living and does not mention any particular deprivation in the 1930s, nor any experience of anti-Semitism. Gag-writing was the same kind of work that started Mel Brooks and Woody Allen down the path to stardom, and it instilled in Wouk a key ethic of the entertainer (or storyteller): “one paramount rule, hold the audience. In radio that rule was life or death.” It was not until he enlisted in the Navy that Wouk first thought of writing a novel—Aurora Dawn, a show-biz comedy about a “radio preacher who soared to such astronomic ratings that he could tangle head-on with the bullying know-nothing soap magnate and his craven admen.” Looking back, Wouk speculates that he turned to fiction simply because it was the first time he did not have to write for a living: “after all, the Navy was feeding, clothing, and sheltering me.” You’d have to look a long time before you found another American writer who credited the Armed Forces as a muse, rather than a hindrance.

If the American Jewish story is, on balance, a very happy one, why are our books so miserable?

From there, Sailor and Fiddler bounces from book to book, telling the story of how each came to be written. There were distractions along the way, especially from Broadway. After a play based on The Caine Mutiny became a hit, Wouk spent a year working with Charles Laughton on a farce that went nowhere. All things considered, however, there are few bold-face names dropped in this book. Wouk seems to have had little to do with the famous writers of his generation; his closest literary friend was the now-obscure Southern novelist Calder Willingham. He is prouder of his friendship with American and Israeli military men, and in fact Sailor and Fiddler is dedicated to two of them: Mickey Marcus, the American officer who died fighting in Israel’s war of independence, and Ilan Ramon, the Israeli pilot who took part in the bombing of the Osirak nuclear reactor.

Wouk’s love of things military might suggest a certain political slant, but in Sailor and Fiddler he avoids contentious issues entirely. His is an old-fashioned patriotism that sees valor and honor as pre-political virtues. Indeed, Wouk detours around just about anything that could be controversial: If he had any love affairs, he doesn’t mention them; his relationship with his children is not plumbed; he remembers bad reviews but doesn’t seem anguished about them. The impression he gives is of a man who loved researching and writing big historical novels and spent his life doing exactly that. Not until the very end of the book does Wouk mention, as if in passing, that he has kept a lifelong diary, which fills “more than a hundred bound volumes.” Those volumes might tell a very different story than the mild retrospective of Sailor and Fiddler, and perhaps one day we will get to read them. For now, Herman Wouk remains what he has been: a rare example of a happy Jewish writer.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.