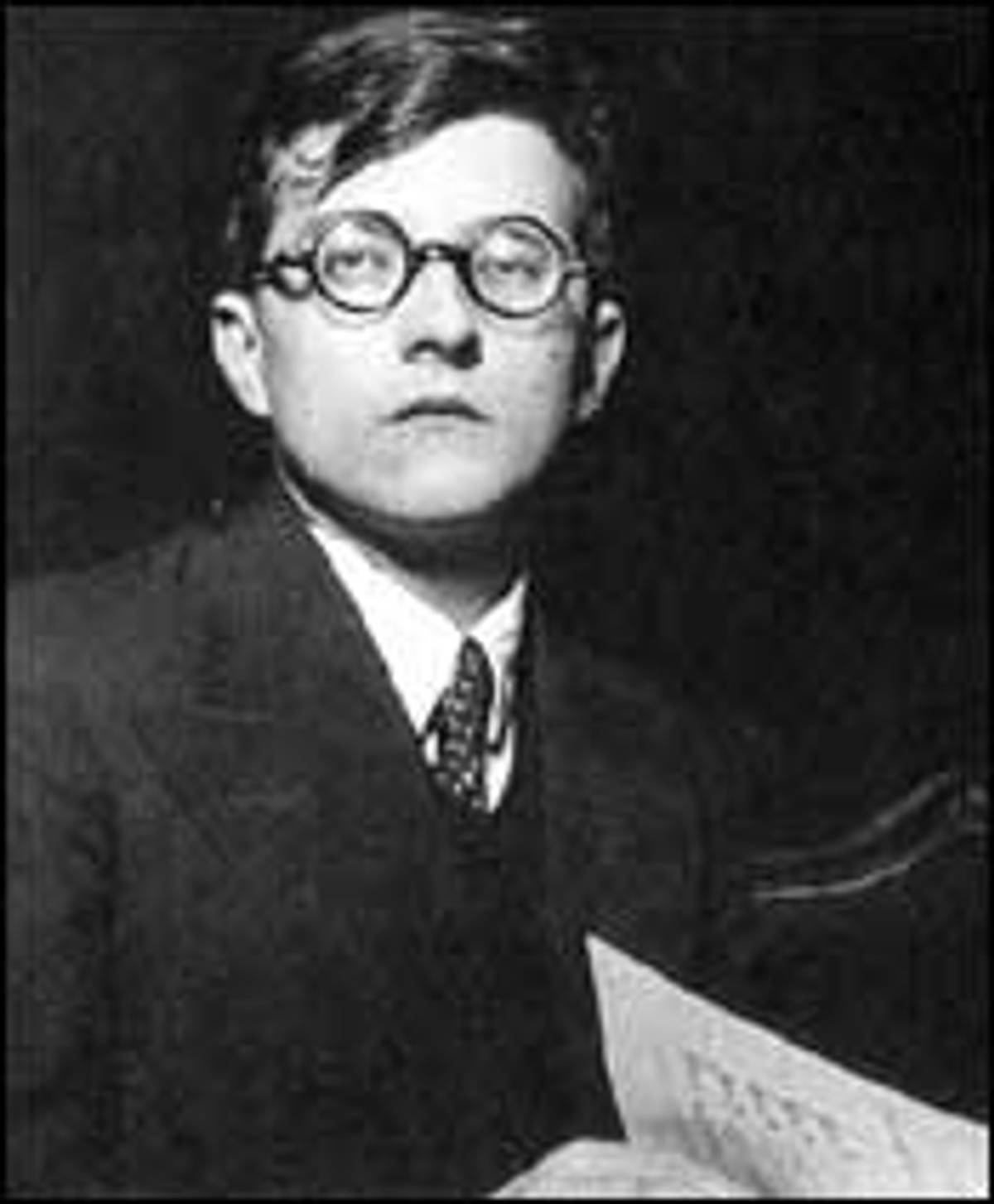

As the Soviet Union’s most famous composer, Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) was many things to many people. For some he epitomized the principled artist, a closet opponent of the Communist regime whose sharp-edged yet deeply anguished music evoked the great suffering of a people under totalitarianism. To others Shostakovich was a Soviet lackey, loyally serving the regime’s political demands by conjuring up fierce, bombastic glorifications of Communist struggle and triumph.

One thing Shostakovich was not was Jewish, by birth or belief. Yet from the frenzied klezmer dance melody of the Second Piano Trio (1944) to the mournful vocal cycle From the Jewish Folk Poetry (1948) to the sweeping sorrow of the Holocaust evoked in the Thirteenth Symphony (“Babi Yar“) of 1962, Shostakovich carried on a lifelong affair with the sound and soul of Russian Jewry. Why would a non-Jewish composer living in one of the modern world’s most bitterly anti-Semitic and repressive societies, where mere possession of Hebrew literature could lead to arrest and imprisonment, choose to make Jewishness a recurrent theme in his work? The answer is tied up with the debate over the man behind the music.

Shostakovich was a Communist Party member and First Secretary of the Soviet Composers’ Union, and his signature appeared on a 1973 letter attacking the dissident physicist Andrei Sakharov. Few doubted his tremendous musical talents, but there was little interest in the West for a composer who seemed such an obedient musical apparatchik.

Then came Testimony: The Memoirs of Dmitri Shostakovitch as Related to and Edited by Solomon Volkov, purportedly dictated shortly before the composer’s death in 1975. Volkov, a senior editor at Sovetskaya Muzyka, the leading Soviet music journal, brought the manuscript to the United States in 1976 and published in English in 1979. Testimony offered a startling image of the quiet, legendarily taciturn composer as a secret freedom fighter, an anti-Soviet liberal who revealed himself only in these private conversations. Volkov’s Shostakovich was boldly courageous and pettily proud, alternately explaining the hidden anti-Soviet political meaning in many of his famous compositions and dismissing former colleagues such as Prokofiev in unflattering, gossipy terms.

The book’s convoluted title was the first indication that this was not a standard autobiography. In fact, charges of forgery immediately began to surface among Soviet authorities and Western scholars. Volkov offered as evidence of Shostakovich’s approval the composer’s signature on the first page of each chapter, certifying that he had read the contents. And in the context of the Cold War and the political movement on behalf of Soviet Jewry, Westerners eagerly embraced the new heroic image of Shostakovich as a secret dissident, making his music a new concert hall favorite and Volkov’s book a bestseller.

Among the themes to emerge from Testimony was the central place of Jews and Jewishness in Shostakovich’s life and creative work. Many of the people closest to Shostakovich were Jews, including his favorite pupil, Venyamin Fleishman, and his best friend, Ivan Sollertinsky. Both men died tragically during World War II, Fleishman as a Red Army soldier and Sollertinsky of illness exacerbated by wartime living conditions. Shostakovich produced musical tributes to each. He completed Fleishman’s unfinished opera, Rothschild’s Violin (1944), based on a Chekhov short story about a Jewish klezmer musician. Sollertinsky he recalled in the mournful, piercing Second Piano Trio, written as word of the Holocaust was reaching Moscow. The final section of this piece includes a freylekhs, a Jewish wedding tune that seems to link the dead and the living in a desperate, sacred dance of joy and sadness.

These are among a dozen major works in which Shostakovich displayed an intense, sustained interest in the larger symbolic meaning of Jewishness and Jewish music. What was the source of this attraction? Testimony provided one answer:

Jewish folk music has made a most powerful impression on me. I never tire of delighting in it, it’s multifaceted, it can appear to be happy while it is tragic. It’s almost always laughter through tears. This quality of Jewish folk music is close to my ideas of what music should be… Jews became a symbol for me. All of man’s defenselessness was concentrated in them. After the war, I tried to convey that feeling in my music. It was a bad time for Jews then. In fact, it’s always a bad time for them.

The problem is we don’t really know if Shostakovich actually said so. In 1980 American musicologist Laurel Fay published an article demonstrating that large chunks of Volkov’s supposedly original oral interviews in Testimony were taken verbatim from previously published articles. The evidence against the book’s authenticity only grew more and more damning over the ensuing years. Leading scholars of Russian music— Fay, Richard Taruskin, Malcolm Hamrick Brown—now agree that Testimony is at best a sloppy embellishment of Shostakovich’s words and at worst an audacious forgery. On the other side of debate are a few highly vocal Soviet émigré musicians and their sympathizers.

Much of the scholarly detective work on Testimony has been assembled in a new anthology, A Shostakovich Casebook. Editor Malcolm Hamrick Brown wants to present the clearest possible case against Volkov’s Testimony; he includes interviews with relatives and close friends, including the composer’s widow, that challenge many factual and linguistic details. Its centerpiece is a new essay by Laurel Fay that exhaustively and conclusively shows that the signatures held up by Volkov as proof that the memoirs were genuine were forged. Despite its slightly monomaniacal air, the Casebook succeeds in demonstrating that Volkov’s Testimony simply cannot be trusted.

Determined not to be outflanked in the Shostakovich wars, Volkov published Shostakovich and Stalin: The Composer and the Dictator, a smooth, erudite attempt to prop up his heroic, cardboard image of Shostakovich. He maintains that Testimony is a faithful document, but because of the “confusion,” he avoids quoting from it, relying instead on a range of colorful anecdotes culled from other interviews and memoirs. Volkov engagingly and skillfully synthesizes decades of complicated Soviet cultural history, but ultimately repeats the thesis first articulated in his introduction to Testimony. To survive under Stalin, Shostakovich adopted the guise of the yurodivy, or “holy fool,” a folk trickster figure who uses craftiness, feigned insanity, and artistic ability to secretly criticize those in power. To demonstrate this subversion, Volkov interprets Shostakovich’s music against his biography, teasing out the hidden anti-Soviet codes in the symbolic language of dark dissonances and jagged rhythms.

Problems with Volkov’s current effort to lionize Shostakovich extend beyond the shadow of Testimony. For instance, Volkov admits he has no convincing explanation—musical or otherwise—for why Shostakovich joined the Communist Party in 1960, when the Stalinist threat was long over and the dissident movement was just beginning. However, on the question of Shostakovich and Jewish music, he zeroes in on a simple, powerful truth: In the postwar Soviet Union, to write music on Jewish themes of any kind was a provocative, explicitly political act, a direct critique of the regime’s anti-Semitism. There is no question, for instance, that a work such as From the Jewish Folk Poetry, composed in 1948, the year in which Stalin began his murderous campaign against the country’s leading Yiddish poets, actors, and writers, was a direct commentary on the brutal Soviet regime. So too the use of Yevgeny Yevtushenko’s poem “Babi Yar“—which caused a scandal upon its initial publication in 1961, when discussion of the Holocaust itself and Jewish suffering was forbidden—as the text of his Thirteenth Symphony. Other recent Russian-language memoirs, such as émigré musicologist Vladimir Zak’s Shostakovich and the Jews (1997), buttress this assertion, documenting how Shostakovich went to great lengths to defend many prominent Jewish musicians targeted by Stalin for persecution. We may not have Shostakovich’s actual testimony, but his music and his actions speak volumes about his respect, compassion, and deep friendship.

Shostakovich fails on all three counts the test once proposed by scholar Curt Sachs, that Jewish music is music created “by Jews, as Jews, for Jews.” And yet in some of his works, Shostakovich used melodies, rhythms, and other musical elements borrowed from traditional Eastern European Jewish folk music. Beneath the thunder of Shostakovich’s archmodern dissonances, the village fiddler and cantor are wailing away. What’s more, Shostakovich’s explicit intention to acknowledge and honor the Holocaust and Yiddish folk poems certainly lends his music a meaningful Jewish theme. These works, then, are Jewish in both form and content.

To that we may add a third factor. A substantial portion of his Jewish audience, in Russia and beyond, continues to claim Shostakovich’s music. Vladimir Zak calls Shostakovich’s musical language a form of Jewish “biblical romanticism.” Rabbi Shlomo Carlebach, the late exponent of American Jewish religious music, spoke of Shostakovich’s music as soaked through with “the sorrow of the Jews…crying out together with the Torah.” And so Volkov’s work, while it may not successfully prove that Shostakovich was a political dissident, does rightly remind us that the great master of modern Russian music was also a great Jewish composer.

James Loeffler is the author of The Most Musical Nation: Jews and Culture in the Late Russian Empire and co-editor of The Idelsohn Project.