A Translator’s Masterpiece

Hillel Halkin’s lifetime of thinking about language, Zionism, and writing pays rich dividends in his ‘indispensable’ new collection of essays devoted to the writers who created modern Hebrew literature out of nothing

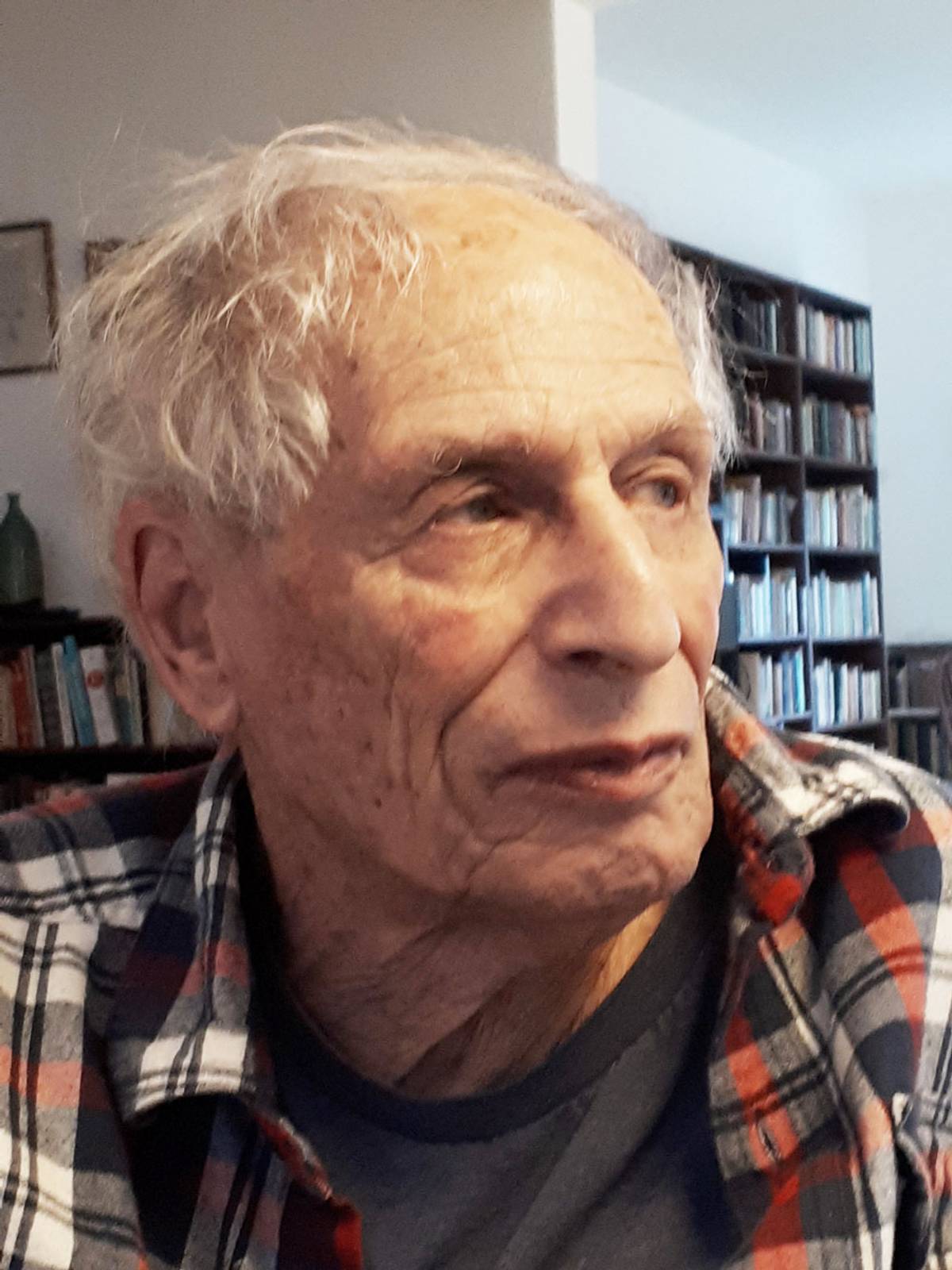

At the age of 81, the writer and translator Hillel Halkin has published his masterpiece—a book that reflects a lifetime of thinking about Hebrew, Zionism, literature, and the relationship among them. The Lady of Hebrew and Her Lovers of Zion is a collection of 11 essays, each devoted to a writer who helped to create modern Hebrew literature in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Each chapter surveys its subject’s life and work, including generous quotations in Halkin’s own translation. But Halkin has created something more than a gallery of individual portraits. The Lady of Hebrew is really a book about how literary ideas can change the world, as well as a penetrating study of crucial period in modern Jewish history.

Halkin is a leading translator of Israeli literature into English, having worked with Amos Oz and A.B. Yehoshua among many others. But Israeli literature is completely absent from The Lady of Hebrew; the most recent work Halkin looks at, S.Y. Agnon’s novel Only Yesterday, was published in 1945, three years before the Jewish state was founded. The earliest, Joseph Perl’s anti-Hasidic satire The Revealer of Secrets, appeared in 1819, long before anyone dreamed that Hebrew could be revived as a spoken vernacular.

Yet as Halkin’s title suggests, the story of modern Hebrew writing is inseparable from the story of Zionism. The writers he discusses—including the poet Chaim Nachman Bialik, the essayist Ahad Ha’am, and the fiction writers Micha Yosef Berdichevsky and Yosef Chaim Brenner—never lived in a Jewish state, but they can be compared to the generation of the Exodus: They didn’t enter the Promised Land, but the journey couldn’t have been accomplished without them.

Like the Israelites in the desert, too, these Hebrew writers were full of doubts, often wondering if they should turn back. “Ah, trusting soul to think that Hebrew has a future and not just a past—a past that will be followed by nothing!” lamented Yehuda Leib Gordon to a friend in 1879, after decades of writing Hebrew poetry. The idea that a modern, secular literature could be created in the Hebrew language was hardly less quixotic than the idea that a Jewish state could be created in Palestine. Both hopes seemed to fly in the face of 2,000 years of history.

After all, Hebrew had ceased to be the main spoken language of the Jews by the first century CE, displaced by Aramaic and Greek. For the next 1,800 years, Hebrew was lashon hakodesh, the “holy tongue” of Torah and prayer, rabbinic commentary and learned correspondence; but it was never the language of everyday life. All of the Eastern European writers Halkin discusses in The Lady of Hebrew grew up speaking Yiddish. Certainly Hebrew wasn’t a language to write novels in; rabbinic Judaism scorned fiction as frivolous if not actively sinful.

That’s why the appearance of Abraham Mapu’s The Love of Zion, in 1853, created such a sensation. Halkin argues that this wasn’t actually the first Hebrew novel—he gives that title to Perl’s book, which appeared three decades earlier—but it was certainly the first to have a sizable readership, and it effectively created modern Hebrew fiction. Today The Love of Zion appears unreadably stilted and artificial; as Halkin shows, practically every phrase is borrowed directly from the Bible, giving the effect of a pastiche. But Mapu’s story of star-crossed lovers, set in Judah in the eighth century BCE, struck his first readers as thrilling. Halkin quotes from a contemporary memoir:

“The novel made its way everywhere, into the academies for rabbinical students, into the very synagogue. The young were amazed and entranced by its poetic flights. … Rabbinical students, playing truant, resorted [to the woods] to read Mapu’s novel in secret. Luxuriously they lived the ancient days over again.”

As this passage suggests, the audience for Hebrew fiction mainly consisted of freethinking young men with an advanced religious education. (Mapu himself was a yeshiva graduate and Hebrew teacher.) The Love of Zion dazzled such readers in several ways. Though written in the holy tongue, it was a story of human conflicts in which God played no role; it was passionately romantic; and it was full of descriptions of nature, converting “the biblical landscape from an abstraction into a reality,” Halkin writes. All of this made a delightful contrast with the legal and religious texts that filled yeshiva students’ days.

In his letters, Mapu imagined the Hebrew language as a personified female figure, the “lady of Hebrew” of Halkin’s title, and addressed her in flowery terms: “Forsake thy domicile and come with me, leave the ancient Eden for the present habitations of thy people.” To actually make Hebrew a part of living Jewish culture, however, it would have to give up the biblical purity of diction that Mapu cherished. Halkin gives a telling example from one of his later novels, The Painted Vulture, which was set in contemporary Eastern Europe. Mapu refers to a theater, almost incomprehensibly, as a “valley of vision,” using a phrase from Isaiah. Halkin points out that he could have used the mishnaic Hebrew word “teatron,” but he shunned any vocabulary borrowed from Greek.

Halkin’s impatience with Mapu shows that he is writing as an engaged critic rather than a neutral historian. The purpose of modern Hebrew literature, Halkin insists throughout the book, was to help bring about a Hebrew-speaking Jewish state, and he judges each of his subjects by how well they understood and furthered this mission. By that standard, Mapu falls short—linguistically, because he straitjacketed Hebrew rather than helping it progress, and politically, because he didn’t arrive at full-fledged Zionism. “What is actually in these novels … is Zionism’s stopping short of emerging, like an idea that trembles on the cusp of consciousness and falls back,” Halkin concludes.

But Mapu had opened a door, and the next generation charged through it. Starting in the 1870s, secular Hebrew writers began to reach a small but elite readership thanks to journals like Ha-Shachar, edited by Peretz Smolenskin in Vienna, and Ha-Shiloach, edited by Ahad Ha’am in Odessa. In their pages, poets and novelists experimented with making Hebrew a modern literary language, while polemicists argued about the Jewish future.

Smolenskin and Ahad Ha’am are among Halkin’s subjects in The Lady of Hebrew, and their stories show how hard it was for even committed Hebraists to envision a hopeful future. Smolenskin proclaimed that the Hebrew language was the Jews’ true homeland: “It puts words in our mouths with which to speak to one another to farthest isles and ends of the earth.” Yet his fictional treatments of Jewish society were bitterly critical. His novel A Donkey’s Burial shows how a spirited young man is crushed by a corrupt community, ending up as an apostate and a criminal. For maskilim, “enlightened” Jews like Smolenskin, Jewish life was in desperate need of rebirth—but where was it to come from?

In the 1880s, a new answer emerged in the form of the Hovevei Zion or “Lovers of Zion” movement, which gives Halkin the second half of his title. After the assassination of Czar Alexander II led to a wave of pogroms throughout Eastern Europe, Jews began to think seriously about the idea of emigrating to Palestine. Only a small number actually took the plunge, creating the first modern Jewish settlements in the land of Israel. But the idea of Zionism quickly transformed Jewish political consciousness, especially after Theodor Herzl convened the first Zionist Congress in 1897.

Hebraists were a natural constituency for Zionism. They were already committed to creating a new Jewish culture that would be secular in content and national in form. One of Smolenskin’s last stories, “A Pact of Vengeance,” is about a young man who converts to Zionism after his family is victimized by a pogrom: “Our flag of vengeance is Jerusalem!” he proclaims. But Halkin shows that there was also a natural tension between the Hebraists’ high-minded cultural Zionism and the practical, political variety of Herzl, who scorned the idea that Hebrew could ever become the vernacular of a Jewish state. After all, he observed, who knew how to buy a railroad ticket in Hebrew?

To write modern literature in an ancient language, secular literature in a religious language, national literature for a nation that didn’t yet exist—these were challenges that Tolstoy and Dostoevsky didn’t have to contend with.

This conflict comes to the fore in Halkin’s chapter on Asher Ginsberg, who under the nom de plume Ahad Ha’am (“one of the people”) became the leading theorist of cultural Zionism. In 1902, Herzl published Old New Land, a speculative novel set in an imagined Jewish state. Reviewing it in Hebrew, Ahad Ha’am attacked both the book and Herzl’s vision of Zionism, which didn’t seem to care if the Jewish state was actually Jewish. For one thing, the residents of Palestine in the novel speak German. “All is a monkey-like aping of others with no show of national distinctiveness,” he complained.

His own program for Zionism was very different. Rather than winning a Jewish state through a grand diplomatic coup, the way Herzl hoped, Ahad Ha’am wanted to gradually build a spiritual and cultural center in Palestine. Most Jews, he believed, would always live in diaspora. The goal of Zionism was to create a Hebrew-speaking community to serve as an inspiration for Jews everywhere—“a miniature of the Jewish people as it should be,” as he put it. Halkin, a Jewish culturist himself, is sympathetic to Ahad Ha’am’s vision, but points out that he was “blind to the menace of anti-Semitism.” The Jews of Europe didn’t have generations to wait for a Jewish culture to be built in Palestine; they needed a refuge immediately.

Both Herzl and Ahad Ha’am knew Palestine only from a few fact-finding trips; neither man thought of moving there himself. It wasn’t until around 1905 that settlement in Palestine became a live option for a new generation of Hebrew writers. The abortive Russian revolution of that year spurred a new round of emigration known as the Second Aliyah, which brought Labor Zionism to Palestine and created the kibbutz movement. A political path to a Jewish state remained unclear, since the Turkish government was adamantly opposed to the idea. Herzlian diplomatic maneuvering wouldn’t achieve a real victory until 1917, when the British conquered Palestine and promised it as a Jewish national home in the Balfour Declaration.

The pioneers of the Second Aliyah didn’t minimize the obstacles, but they were driven by the kind of irrational faith that forces history to bend to its will. In The Lady of Hebrew, this cohort is represented by Yosef Chaim Brenner and A.D. Gordon, the first major Hebrew writers who actually made aliyah. They were diametrically opposed in temperament, yet shared a conviction that Jewish life needed to be completely transformed. Gordon settled in Palestine at the advanced age of 48, throwing himself into a life of agricultural work for which nothing in his earlier career had prepared him. His essays extolled labor and the land in terms that fused kabbalism and Tolstoyan socialism: The Jewish farmer, he wrote in “Man and Nature,” was “a partner in the labor of Creation.”

Brenner, by contrast, was a Dostoevskyan figure, a tormented intellectual unable to believe in any creed. His first novel, In Winter, published in 1903-4, is narrated by a Brenner surrogate named Yirmiya Feierman, who goes through a crisis of faith and emerges a self-hating nihilist: “If I were to listen to the voice of inner reason, I … would not go on living for another minute.” If Gordon’s Zionism was an expression of religious faith, Brenner’s was a revolt against despair. In Palestine he hoped to escape what he saw as the fatal deformation of the Jewish spirit in diaspora.

As Halkin shows, the Yishuv he joined in 1909 was far from flourishing, and in his fiction he trained his unsparing gaze on its defects and illusions. In Brenner’s last novel, From All Sides, he once again fictionalized himself as Oved Etsot, a young man who comes to Palestine, struggles, gets sick, and finally leaves. But Brenner himself stayed, in part because he was inspired by the faith of Gordon, who features in the novel under the name Aryeh Lapidot. “The man, in his quiet way, is a hero,” Oved says about Aryeh. “Prayer like that could make me get down on my knees and pray, too.” Brenner spent the rest of his short life in Palestine; he was murdered by Arabs during a riot near Jaffa in 1921, when he was 39 years old.

Brenner is perhaps the first writer in The Lady of Hebrew who seems compelling on literary rather than historical grounds. (Two volumes by Brenner are in print in English, including Halkin’s translation of Breakdown and Bereavement. Like The Lady of Hebrew, they are published by Toby Press.) But of all the Hebrew writers discussed in The Lady of Hebrew, Chaim Nachman Bialik was the first to stake a claim to literary greatness. More accurately, greatness was thrust upon him whether he wanted it or not. By the early 20th century, Hebrew literature and Zionist consciousness had developed to the point where a national poet was demanded, and Bialik fit the bill. His long poem “In the City of Slaughter,” a bitter response to the Kishinev pogrom of 1903, made a Zionist case for Jewish self-reliance and self-defense. Certainly the poem’s God wasn’t about to rescue His people: “My heart goes out to you, my sons, it truly does./You died in vain, and neither you nor I/Know what you perished for or why.”

Halkin’s chapter on Bialik is the longest and most critically ambivalent in the book. It is titled “He Who Could Have Set the World on Fire,” quoting a damning description of Bialik by a woman named Ira Jan, who loved him and whose love he rejected. Like her, Halkin has a sense that Bialik didn’t live up to his destiny as a national poet. His real genius was for sad, meditative lyrics; when he tried to write a symbolic national epic, “The Scroll of Fire,” the result was a disappointment: “They’ve taken our Bialik, the quintessential artist, and made a prophet of him!” declared one reviewer. Bialik stopped writing verse in his late 30s, focusing instead on editorial work; by the time he moved to Tel Aviv in 1924, his poetic career was mostly over.

Halkin pays intelligent, loving attention to Bialik’s work, as he does with all of his subjects. His original translations show each writer to best advantage, while also serving as a running commentary on the evolution of modern Hebrew into a flexible literary instrument. Yet there’s always at least a hint of impatience in Halkin’s critical stance, a sense that none of these writers managed to solve the quandaries of modern Hebrew literature. Of course, that’s because they were insoluble. To write modern literature in an ancient language, secular literature in a religious language, national literature for a nation that didn’t yet exist—these were challenges that Tolstoy and Dostoevsky didn’t have to contend with. If they had, maybe they wouldn’t have become Tolstoy and Dostoevsky.

For Halkin, the destiny of modern Hebrew writers wasn’t to produce masterpieces but to serve as a spiritual “government-in-exile” for the Jewish people—one that “seemed unlikely, to say the least, ever to have a land or a people to rule.” The emergence of a Hebrew-speaking Jewish community in Palestine isn’t directly attributable to these Hebrew writers—Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, who did more than anyone to resurrect spoken Hebrew, appears in The Lady of Hebrew but isn’t one of Halkin’s main subjects. But it certainly wouldn’t have happened without them.

Now that a Hebrew-speaking society exists, do these writers still have anything to say to it? In his concluding chapter, Halkin writes about watching a group of teenagers windsurfing on the beach near Haifa, and realizing that they are totally oblivious to the literary and intellectual struggles that made their lives possible: “They weren’t worried about the future of their country or troubled by Jewish history. They didn’t care what anyone thought of the Hebrew they spoke. They didn’t know about Ahad Ha’am or Berdichevsky. They had never read a line by either of them and never would.”

In a sense, this ability to live in the present is the fulfillment of the Zionist dream, which always hoped to give Jews a “normal” existence in a country of their own. “All this soul-searching—all this picking and picking at the Jewish soul—who needs it?” Halkin asks. But for better or worse, there will always be a few readers who can’t leave the tormenting problems of Jewish identity alone; and for them, The Lady of Hebrew is an indispensable book.

Adam Kirsch is a poet and literary critic, whose books include The People and the Books: 18 Classics of Jewish Literature.