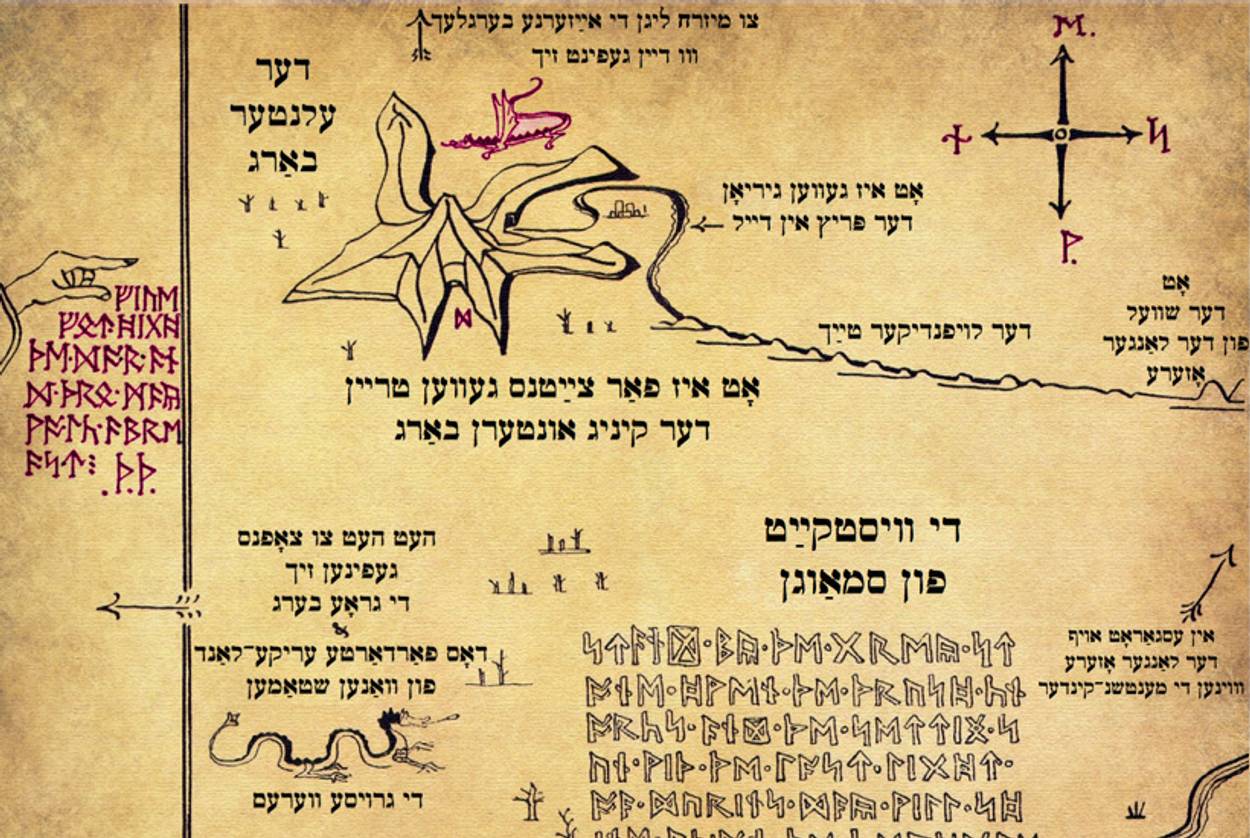

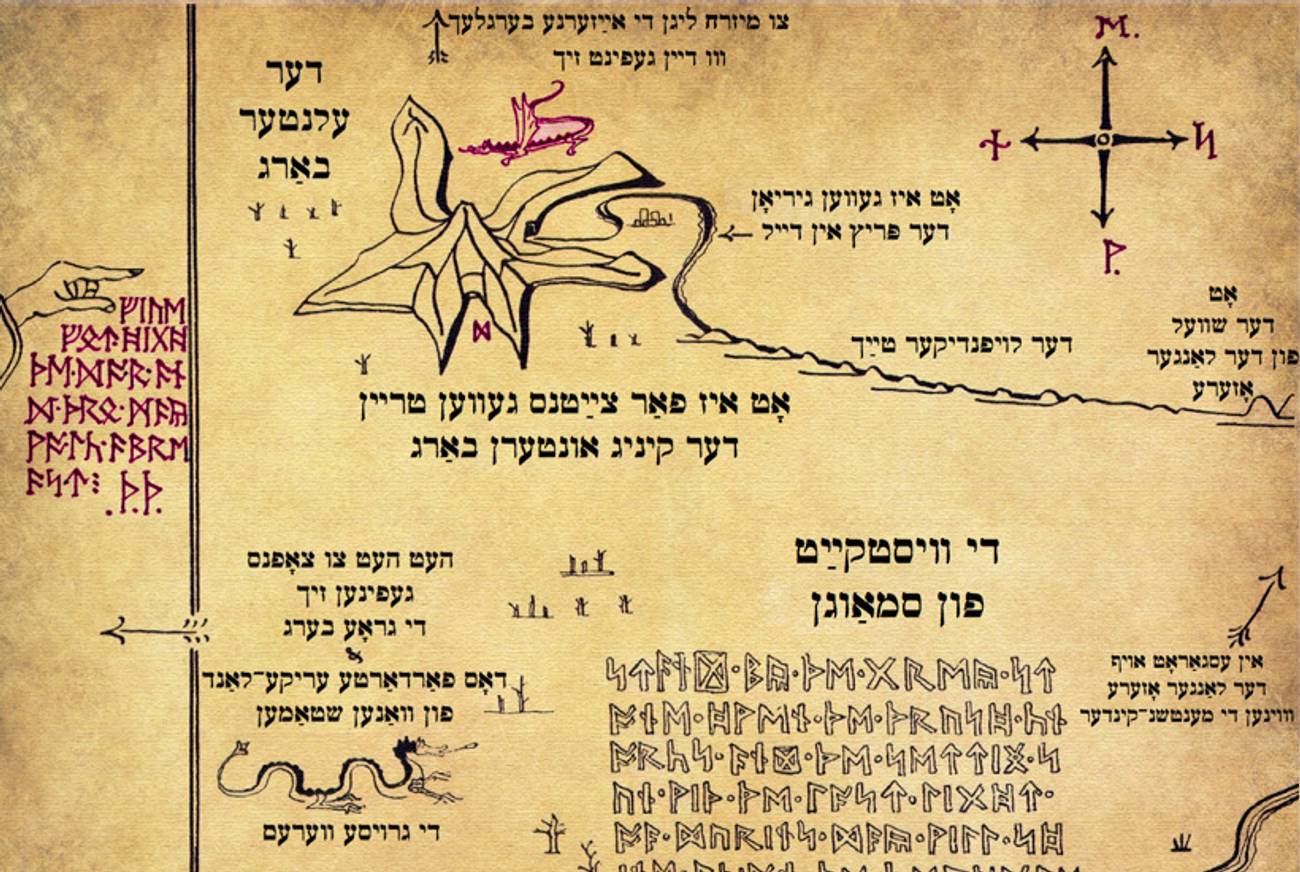

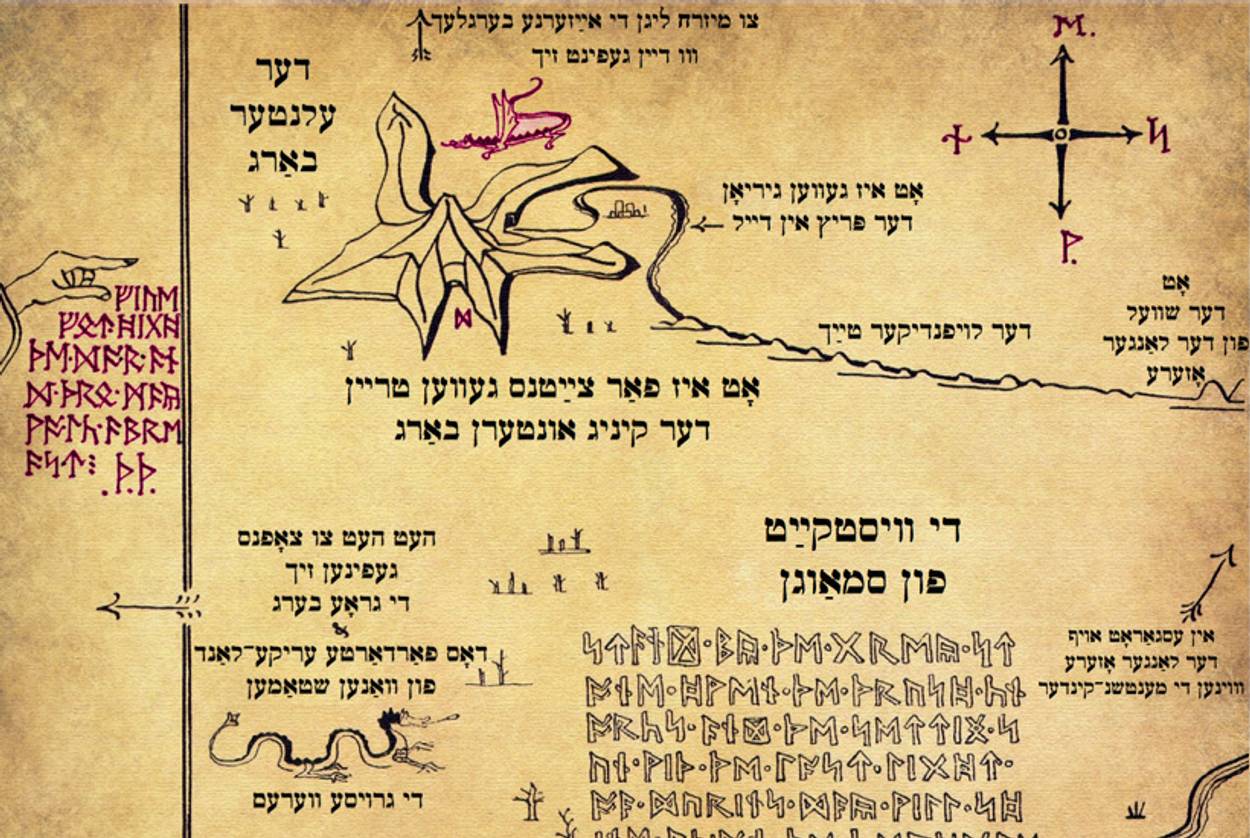

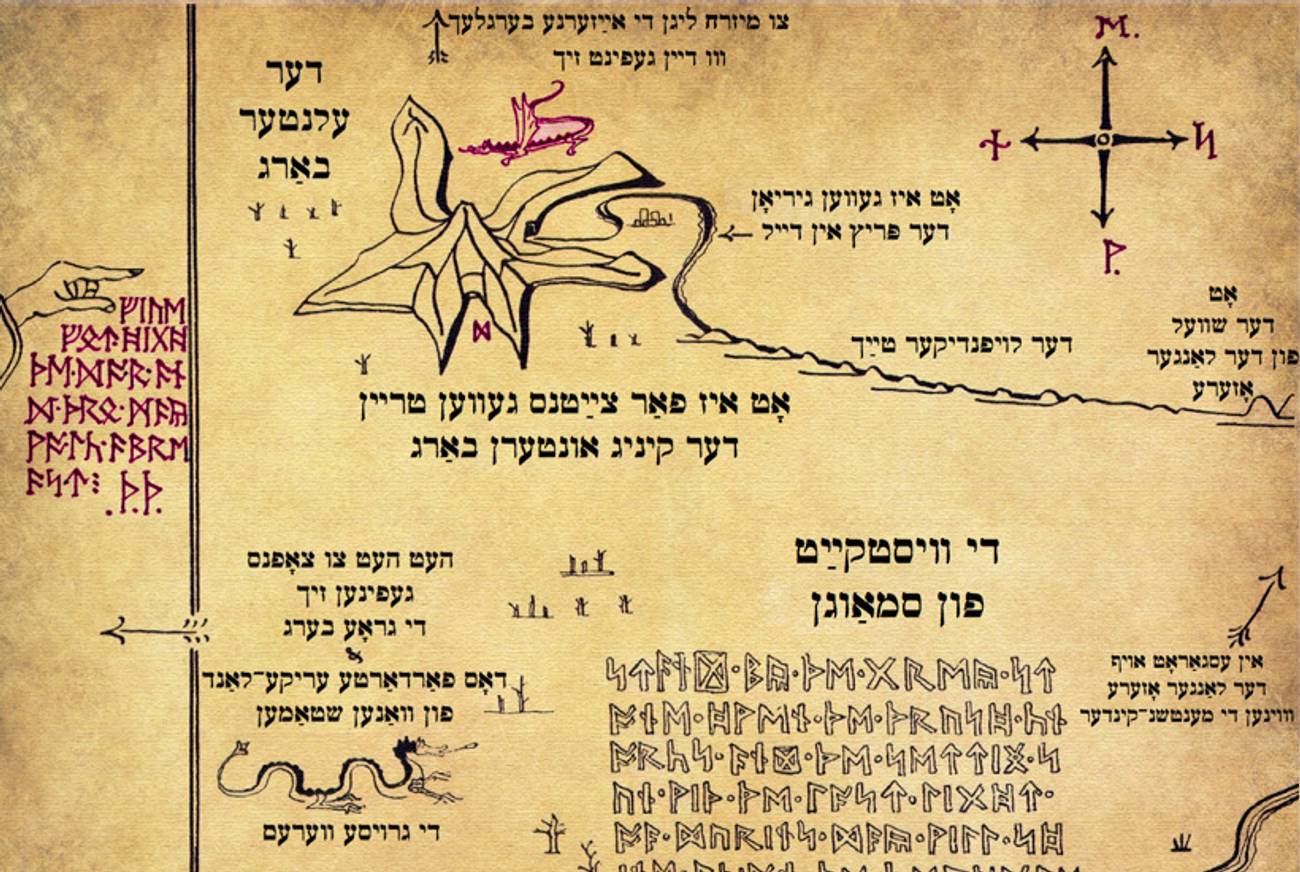

Yiddish-Speaking Wizards and Dragons Invade the Shire in ‘Der Hobit’

J.R.R. Tolkien’s foremost and only Yiddish-language translator is part of a new wave of nonscholar enthusiasts

For one of his first translation projects after his retirement, Barry Goldstein, a former computer programmer, found an empty table at his local Starbucks in Boston and settled in to work on the “Treebeard” chapter from J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings trilogy. But Goldstein soon realized that he needed something more sizable to occupy his time: 95,022 words later, he had translated the entire text of The Hobbit, the prequel to the Ring series, into Yiddish.

Only a little more than 130 copies of Goldstein’s translation have sold since it was released in December. But as Goldstein tells it, he always knew Der Hobit wouldn’t be a best-seller, and the sales were still double his original two-figure estimate.

In the heyday of Yiddish literature, the translation of literary classics into the mamaloshen was entirely commonplace. The prewar Yiddish readership is estimated at about 10 million—many of whom spoke Yiddish as their first language and had a rabid appetite for the classics of world literature. Some of the best-selling Yiddish adventure stories included gems like Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, Jack London’s Klondike series, and Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. “There was a sense that we had to catch Yiddish up with the world and modernism and that any important literary phenomenon that was taking place in the larger world had to be conveyed to the Yiddish-speaking world,” said Miriam Udel, a professor of Yiddish at Emory University. “The cultural ambitions of Ashkenazic Jewry were on the grandest scale, so they didn’t think of themselves as having a small or minority literature or a cultural complex.”

Today most of the world’s more than 1 million Yiddish speakers are used to doing much of their reading in some other language, primarily Hebrew, English, Russian, or French. Readers in ultra-Orthodox communities, who make up a large plurality of those whose primary language is Yiddish, are restricted in what they can read by religious customs and edicts. As the publication of Der Hobit shows though, the quirky, personal interests of translators ensure that popular books still make their way into Yiddish, where they can be read by anyone who knows the language.

For Goldstein, the act of translation was not only a gift to his mother tongue, but also surprisingly relaxing. “After years of obsessing about complicated computer programs, I found reproducing the Trolls’ grobe diburim,or rhyming poems, to be challenging enough, but much less stressful than wrestling with a recalcitrant computer,” he explained. “It drew me right in.”

While Goldstein grew up in a Yiddish-speaking home—his father’s roots were in Lithuania, and his mother was born in Kaminets-Podolsk—he never took to the language as a child. In fact, he vividly remembers the time that he escaped through a window in order to cut class at the Jewish school where he learned Yiddish. Years later though, he started taking Yiddish classes and soon found himself as J.R.R. Tolkien’s foremost and only Yiddish-language translator.

For two to three hours a day, sometimes as many as six days a week, he contemplated how to accurately render Tolkien’s fantastical and heavily Celtic-inflected, Middle-earth dialects into a language rich with its own parables and folk traditions. “The day-by-day process was just page by page,” Goldstein said. He added that he had made about six or seven edits of the text, while also noting that there haven’t been too many people who have asked him much about his process as a translator.

As usual with translation, the fun and the heartbreak are in the details: Rivendell got a phonetic spelling, although it could have been translated in a more conceptually accurate and suggestive way that would have carried the meaning rather the sound of the name. An intricate nest on top of a mountain crag became a hoych nest. Gandalf began to say laden to express his distress, which seems about right for the haimische wizard with the long beard.

But when Bilbo Baggins played with the meaning of his name in a long discussion with the dragon Smaug, Goldstein was forced to admit defeat. “There’s no way to do it, there’s just no way to translate it,” Goldstein said. “So, I put in a footnote and said, ‘This is a pun and I give up.’ ”

Goldstein is not the only one translating well-read books into a little-read language for fun. Other Yiddish hobbyists of late have ensured that classics like Winnie the Pooh and Curious George can take their rightful place in the Yiddish literary canon alongside The Adventures of Mottel, by Sholem Aleichem and Tales of Mendele the Book Peddler, by Mendele Mocher Sforim, i.e., S.Y. Abramovitsh. As Tablet magazine contributor Zackary Sholem Berger, who translated Dr. Seuss favorites like The Cat in the Hat and One Fish Two Fish, Red Fish Blue Fish, agreed, “It’s about the challenge and interest of translation.”

The outsize number of Yiddish-language enthusiasts who share an interest in Goldstein’s labor of love has even influenced an alternative approach to translation itself. Ten years ago, an international panel of distinguished scholars chose titles for the New Yiddish Library series at Yale University Press and commissioned a run of high-quality translations. According to Aaron Lansky, founder of the Yiddish Book Center, though, the scholars soon discovered that almost all of the members of the editorial board were trained by the same handful of people and were therefore familiar with the same few hundred Yiddish-language titles.

“Very few were familiar with the rest of the 40,000 titles of modern Yiddish literature, not to mention countless stories and essays published in more than 3,000 discrete Yiddish newspapers and magazines,” said Lansky. As a result, the Yiddish Book Center has begun soliciting proposals from translators themselves in what Lansky calls “a more Wiki approach.” The new, bottom-up method means that the predilections of Yiddish scholars no longer determine which titles are commissioned for translation. Instead, it is Yiddish-language enthusiasts who choose which books get translated, by translating their favorite books.

In the meanwhile, Goldstein remains committed to ensuring that his own favorites make their way into Yiddish. Upon finishing Der Hobit, he celebrated with a few drinks and wondered whether he had preserved Tolkien’s unique style. Then he realized that he missed the work. “It became strangely addictive,” Goldstein said. At first he decided to attempt to translate Charles Dickens’ Pickwick Papers, which also seems peculiarly suited to Yiddish, but then he missed his old friends. “I’ll likely put that aside for a while,” he admitted, “and try The Fellowship of the Ring.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Natalie Schachar is an editorial intern at Tablet. A recent graduate of Barnard College, she has written for the Times of Israel, The Atlantic, The Argentina Independent and Lilith Magazine.

Natalie Schachar is an editorial intern at Tablet. A recent graduate of Barnard College, she has written for the Times of Israel, The Atlantic, The Argentina Independent and Lilith Magazine.