Sunday Streamers

Tablet’s film critic proposes five Jewish film-canon essentials to watch at home: a noir, a poetic horror flick, two examples of the 1960s Jew Wave, and a crime story

It may be a new year but 20/20 vision persists. Meaning: Movie houses are still closed and streaming rules. Herewith a selection of near-essential English-language movies that might belong in the Jewish canon—a film noir with an inappropriately innocuous title, a poetic horror flick that sounds more lurid than it is, two prime examples of Hollywood’s late-’60s Jew Wave, and an atmospheric East End crime story all but unknown in the United States.

Mank, the story of Herman Mankiewicz’s connection to Citizen Kane, has stirred interest in Mankiewicz’s other scripts. None come close to Kane although I do have a fondness for Christmas Holiday (1944). Freely adapted from a Somerset Maugham novel that has nothing to do with Christmas, it’s a weird concoction in which Mankiewicz’s contribution (a solo credit) is only one component.

Unfolding mainly in flashback until the past violently erupts into the present, Christmas Holiday could almost be a joke on the wildly popular Holiday Inn, the 1942 Paramount movie that featured Fred Astaire, Bing Crosby, and Irving Berlin’s “White Christmas.” A tale told by a crypto-hooker to a jilted GI stranded by bad weather in New Orleans on Christmas Eve (poor baby), Christmas Holiday’s misleading title is amusingly amplified by the presence of musical stars Deanna Durbin and Gene Kelly.

Durbin, a cheerful little earful who was then Universal’s biggest attraction, plays the resident chanteuse in a sleazy roadhouse (i.e., “bordello”). Kelly, fresh from his breakout role as a charming heel in the Broadway production of Pal Joey, is her soul mate—a compulsive gambler turned sociopathic killer. Durbin does get to sing, biting off the words in a hard-boiled version of Frank Loesser’s ballad “Spring Will Be a Little Late This Year,” however Kelly’s tap dancing is all verbal. There’s also a memorable supporting turn by Gale Sondergaard (the slinky villainous in the previous year’s Sherlock Holmes and the Spider Woman) as Kelly’s overly devoted mother.

Christmas Holiday was produced and directed by two German Jewish émigrés, Felix Jackson (then married to Durbin) and the onetime Hitchcock rival Robert Siodmak, who knocked it off between two other Universal productions, quintessential noir Phantom Lady and the camp classic Cobra Woman. Considering that Mankiewicz and Loesser were also German Jews (albeit American born), Christmas Holiday is one of the most Teutonic of Hollywood movies—a heritage borne out by its moody lighting, expressionist compositions, a soupçon of Krafft-Ebing, and long excerpts from Wagner’s “Liebestod.”

The critic Andrew Sarris once observed that Siodmak’s American movies were more German than his German ones. In Driven to Darkness: Jewish Émigré Directors and the Rise of Film Noir, Vincent Brook argues that Siodmak’s American movies were also more Jewish, maintaining that “feminization is the Jewish trope that leaps most immediately to mind. More than those of any other director … Siodmak’s noirs feature female protagonists or strong women in key secondary roles not exclusively relegated to the femme fatale.” (Brook also makes the point, which may or may not be related, that Siodmak was a rare Hollywood Jew who remained married to his Jewish wife.)

Durbin isn’t as relentless as the spunky protagonist of Phantom Lady or as imperious as the queen in Cobra Woman but the role allowed her to express a hitherto concealed strength. At her peak in 1947, she was the highest paid woman in the United States and perhaps the most alienated star in Hollywood. Having failed to get a comparable role to her part in Christmas Holiday, she retired from movies.

You can find a decent print on YouTube.

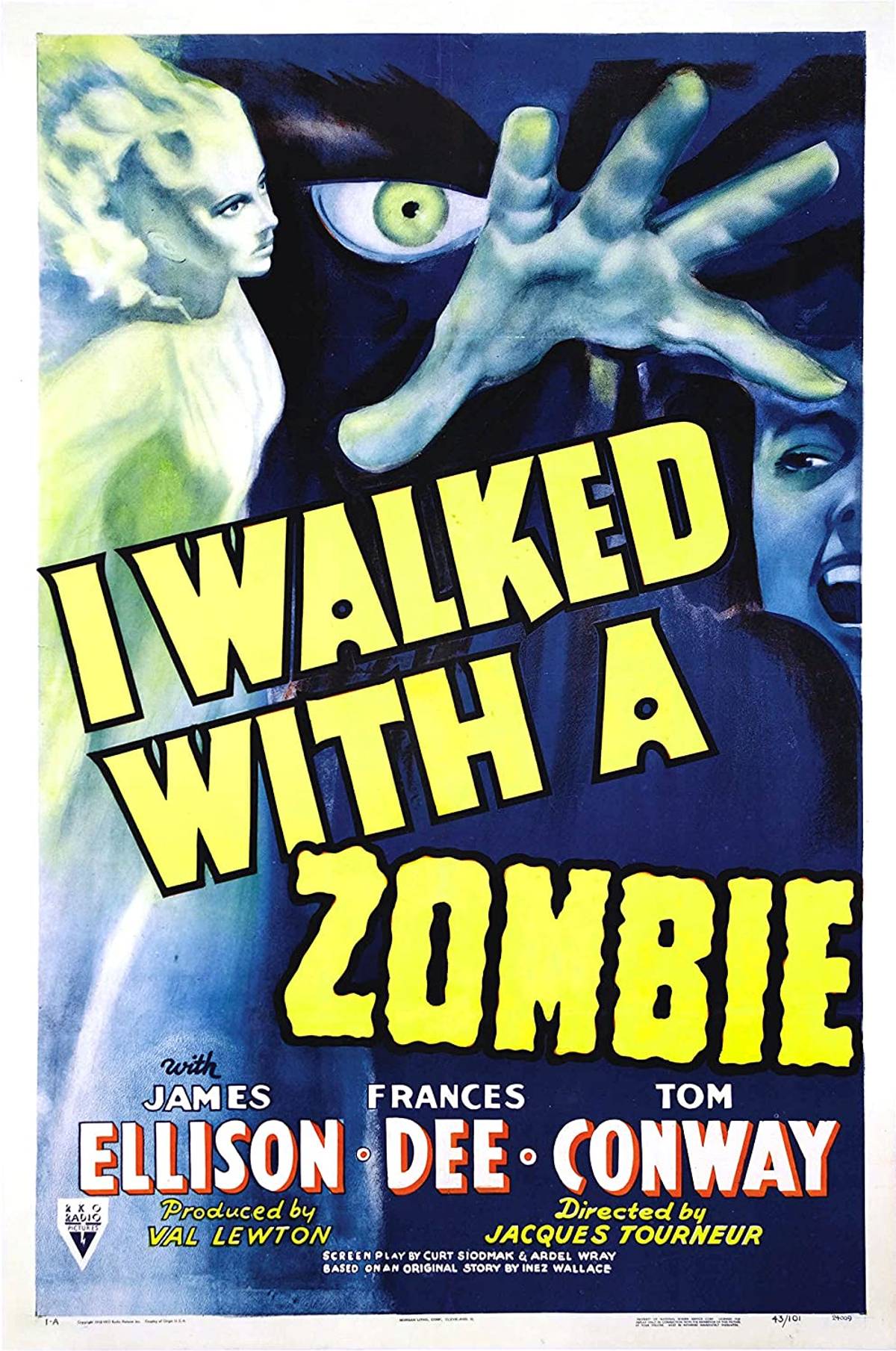

Siodmak’s younger brother Curt (whose great contribution to the horror genre was the invention of the Wolf Man in 1941) had a hand in the making of the 1943 thriller I Walked with a Zombie—a poetic gem that is arguably the greatest of the half-dozen or so B pictures that Val Lewton, the child of Russian Jewish converts to Christianity, produced for RKO during World War II.

Erudite, literary and never totally comfortable in Hollywood, Lewton pioneered a new sort of horror movie. Shock was second to atmosphere. The supernatural was a function of the psychological. Horror was predicated on the power of suggestion. Revered by connoisseurs, these deceptively modest movies are required viewing for any aspiring filmmaker.

Thanks largely to the U.S. occupation of Haiti (ordered by Woodrow Wilson in 1915, ended by FDR in 1934), voodoo and zombies were subjects of popular fascination as well as ethnographic interest. I Walked with a Zombie borrows its title from a sensational magazine story but effects a magical synthesis, using material lifted from Zora Neale Hurston’s 1936 study of Haitian folklore to rework the plot of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre (soon to be filmed as a vehicle for Orson Welles).

Although never less than a movie, I Walked with a Zombie is part of literature as well. It predates and may have even inspired Jean Rhys’ brilliant Jane Eyre prequel Wide Sargasso Sea; it is also one of the movies described in Mario Puig’s Kiss of the Spider Woman. Fluidly directed by Jacques Tourneur, Zombie unfolds in a series of dreamlike vignettes. A willfully innocent Canadian nurse arrives in Saint Sebastian, a Caribbean island very much like Haiti, to care for a brooding white planter’s mysteriously bewitched wife and falls in love with the planter.

The wife is one of the movie’s two zombies. Tall, silent, and glassy-eyed, she has the flowing hair and garments of the surrealist painter Leonora Carrington’s willowy somnambulists. The scene in which the nurse leads her through the sugar cane fields at dusk to a secret voodoo ritual guarded by the movie’s other zombie is among the greatest sequences in the Lewton oeuvre. It also struck some as highly disturbing. The New York Times review is astoundingly judgmental:

With its voodoo rites and perambulating zombie, I Walked With a Zombie probably will please a lot of people. But to this spectator, at least, it proved to be a dull, disgusting exaggeration of an unhealthy, abnormal concept of life. If the Hays office feels it has a duty to protect the morals of movie-goers by protesting the use of such expressions as ‘hell’ and ‘damn’ in purposeful dramas like In Which We Serve and We Are the Marines, then how much more important is its duty to safeguard the youth of the land from the sort of stuff and nonsense that their minds will absorb from viewing I Walked With a Zombie.

This rant is all the more interesting in that by the Hollywood standards of 1942, Zombie was a progressive movie in dealing with issues of race. The white principals are overshadowed in every way by the supporting cast—the multitalented, often-cast and scandalously underappreciated Theresa Harris, the Trinidadian calypso singer Sir Lancelot (popular with left-wing folkies) and the physically imposing Darby Jones, here a mute, slow-moving zombie. The film not only makes the obvious equivalence between the creation of zombies and the institution of slavery but explicitly shows the white planter family, who have the figurehead of a slave ship as a fountain. in their garden, as slavery’s beneficiaries while Jones’ towering figure, guardian of the crossroads, is less a monster than a monument to misery.

Available for rental streaming from a variety of sources: YouTube, Amazon Prime Video, iTunes, etc.

As tiresome as Woody Allen has become, it’s refreshing to revisit his early films. Bananas (1971), Allen’s second self-directed vehicle, is a reminder of young Woody’s comic gifts (not just one-liners but sight gags and physical comedy). It’s also an inventive piece of filmmaking, full of cinephilic references and most evocative of the period during which it was made. As an American new wave film, Bananas is surprisingly similar to Brian De Palma’s independent comedies, Greetings (1968) and Hi Mom (1971), as a Hollywood Jew Wave it’s just below The Producers and Where’s Poppa?, movies by fellow Sid Caesar alums, Mel Brooks and Carl Reiner. Indeed, a mock TV ad for “New Testament cigarettes” got the movie a C (for condemned) rating from the National Catholic Office for Motion Pictures.

Shot largely in New York, Bananas has its documentary aspects. A candy store’s magazine racks are crammed with (now) vintage skin mags, Allen’s Lower East Side crib boasts multiple police locks, and a baby-faced Sylvester Stallone materializes (uncredited) as a menacing punk working the subway. Best of all, Allen makes tremendous use of sportscaster Howard Cosell. The comically self-regarding Cosell announcer first reports, Wide World of Sports style, on an assassination in a Central American dictatorship and, as the film ends, provides play-by-play coverage of Allen’s wedding night with fellow neurotic Louise Lasser. (The pair had been married and their rapport—including a whiny breakup scene that surely gave lessons to Albert Brooks—is hilarious.)

Although their career paths are similar and she has appeared in his plays, Elaine May is Woody’s antipode. While he has made far too many movies, she hasn’t been able to make nearly enough—only four. Each, however, is choice.

May directed herself in her debut feature, A New Leaf (1971), a perverse update of a 1930 screwball comedy, filled with comic supporting characters and society idiots, in which she played a new sort of schlemiel female. Fabulously wealthy and endearingly clumsy, May’s Henrietta is a nerdy botanist whose main indulgence is a taste for Manischewitz Extra Heavy Malaga with soda and lime. She’s stalked by Henry (Walter Matthau), a newly impoverished playboy who plans to murder her for her money.

Matthau makes an amusingly irascible lady killer but May’s performance is unique. She’s naturally attractive and devastatingly klutzy—not a Lucille Ball-like cutup but an expert impressionist who appears to be mimicking several autistic traits. A New Leaf fared poorly at the box office but it has benefited from the belated May revival, selected in 2019 for the Library of Congress’ National Film Registry. Like Bananas, it can be rented from Amazon Prime.

A prime example of the U.K.’s post-WWII, working-class crime films, directed by Robert Hamer in 1947 (two years before his comic masterpiece Kind Hearts and Coronets), It Always Rains on Sunday might be called “kitchen-sink noir.” An escaped convict returns to the old neighborhood, London’s blitzed-out East End, is hidden by his old flame Rose (Googie Withers), a former barmaid, now respectably married to an amiable bloke with two teenage daughters. Domestic squabbling is as constant as the rain.

Aside from the escaped con, everyone is some sort of prisoner. Irascibly presiding over a cramped row house redolent of boiled potatoes and fried kippers, Rose manages to keep her lover under wraps … but only up to a point. While the manhunt provides constant tension (as well as a knockout chase finale that winds up in an active train yard), the movie is rich with incident—petty crimes, would-be seductions, a fixed boxing match—and atmosphere, with several scenes set in and around the outdoor market, Petticoat Lane.

There’s also a smattering of incidental Yiddish, thanks to the extended Jewish family that rubs up against Rose’. The clan features a philandering weekend saxophonist, his gambler brother (what the Brits call a “spiv”), socially conscious sister and traditional father. The latter is played by London’s leading Yiddish actor Meier Tzelniker; the brothers by two young Jewish actors, John Slater and Sidney Tafler. (Eleven years later, Slater created the role of Goldberg in East Ender Harold Pinter’s first production of The Birthday Party; a decade after that Tafler played Goldberg in William Friedkin’s movie version.)

It Always Rains on Sunday can be streamed via Kanopy.

J. Hoberman was the longtime Village Voice film critic. He is the author, co-author, or editor of 12 books, including Bridge of Light: Yiddish Film Between Two Worlds and, with Jeffrey Shandler, Entertaining America: Jews, Movies, and Broadcasting.