Hofesh Schecter Makes ‘Fiddler’ Dance

The Israeli choreographer behind the acclaimed new Broadway revival updates the peasant vibe of an American classic

When Hofesh Shechter was offered the position of choreographer for the newest Broadway revival of Fiddler on the Roof, he hesitated. After eight years of sending shock waves through London with his visceral dance-theater productions he had become quite an in-demand artist in the world of contemporary dance. “As a contemporary choreographer and musician, I was not sure if Broadway was for me. But then I remembered Fiddler’s music. After growing up doing folk dance in Jerusalem, I felt this production was part of my DNA.”

The revival at New York’s Broadway Theater, directed by Bartlett Sher, comes 52 years after the original production was staged and choreographed by American dance legend Jerome Robbins. The musical, with a book by Joseph Stein and music by Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harnick, was adapted from stories by the Yiddish writer Sholem Aleichem. As most American Jews likely know, Fiddler is a story of life, love, and transition, carried by Tevye the dairy man, in the fictional Russian Jewish shtetl of Anatevka at the turn of the 20th century.

Most elements of the current revival are closely modeled after the original 1964 production. Danny Burstein gives an impressive performance as Tevye, rivaling both the great Topol and Zero Mostel, as the comedic, conflicted, and soulful protagonist. Other notable performances include Adam Kantor as Motel the wimpy yet lovable tailor, and Samantha Massell as Hodel, Tevye’s prickly daughter who pushes her father’s sense of tradition with her engagement to Perchik, a radical Jewish socialist.

But strikingly, the show veers from tradition in its choreography. There are five major dance sequences: the opening folk dance, a tipsy toast-turned-fête in a tavern, a dream sequence featuring a series of ghosts, a wedding celebration, and another nostalgic, illusory sequence in which Tevye has a vision of his daughter Chava. In all of these sections the dancers depict villagers whose movements express ritual, pride, and euphoria.

While Robbins’ original concepts provide the foundation of the play, Shechter’s modern version intensifies the emotional volume. Robbins was a ballet dancer and Broadway showman, and his original work is full of Cossack-inspired high kicks, multiple spins, jumps and squats from the floor. In Shechter’s Anatevka there are still elements of acrobatics and bravura, but the folk dancers are grittier and less delicate. They vibrate with a percussive, spiritual energy, closing their eyes, shimmying their shoulders, and flicking their fingers. Shechter’s villagers are earthier, lower to the ground, more adept at floor work as they slide on the stage.

The scene most similar to the original production is the iconic bottle dance in the wedding scene. Five men dance, linking arms, sliding in incredible unison on their knees, while each balancing a bottle of wine on their heads. According to Marla Phelan, the show’s dance captain, Shechter was passionate about keeping this crowd-pleasing scene intact, but he added subtle elements to modernize it. The moments of calm concentration are juxtaposed with unbridled joy and release. The Hasidic Jews at this wedding do not just wave their arms gracefully above their heads, they tremble before their God, writhing in an ecstatic trance.

“Hofesh kept coming back to the idea of pride. Pride in who you are as a people and as a community,” said Phelan recently. “There was a rawness that made it feel more real. It wasn’t a ballet show of folk dance, and yes it was more modern, but it was a very real folk dance.”

Phelan, dressed as a boy in all but one section, reveals another modern twist in this new production. Contemporary dance often features female dancers in non-gender-specific roles, and this production follows suit. Phelan was given all the same movements as her male counterparts. Her only role as a female is as one of three dancers in the dream sequence with Chava. In stark contrast to Robbins’ version of feminine arabesques and soft, flowing turns, Shechter’s female villagers stamp their feet, reach their hands to the sky, and daven in a similar fashion to their fathers and brothers that surrounded them in the town.

More than 50 years after the original, it is expected that the movement in a revived musical like Fiddler will and should reflect new approaches to choreography. What stands out about this particular version is Shechter’s vastly different philosophy regarding Jewish culture, its reflection in dance, and the general meaning of the play.

Jerome Robbins, who changed his named officially from Jerome Wilson Rabinowitz in 1944, was the son of Eastern European Jewish immigrants and an artist who dedicated his life to creating an American style in dance. As ballet critic Jennifer Homans writes in her book Apollo’s Angels: A History of Ballet, “It was the classic immigrant story, and Robbins’ life was marked by an intense emotional attachment to the old world and an opposite equally strong desire to assimilate and make it in the new.”

Robbins had already achieved great success before his direction of Fiddler, including dancing with George Balanchine and creating choreography for prestigious institutions such as the New York City Ballet and Broadway hits including the King and I, The Pajama Game, and West Side Story. Fiddler was more than a show for Robbins, it was a reflection of his own conflicted struggle with his heritage—a way to pay tribute to his ancestors all while reinventing them in a brighter, shinier image.

According to theater scholar Alisa Solomon in Wonder of Wonders, “Making Fiddler, Robbins reclaimed that discarded part of himself and in so doing, returned it, in a glittering package, to those audience members who also had left it behind.”

While clearly a celebration of the Jewish odyssey, Fiddler on the Roof has been criticized over the years for its overt attempt to prettify the Jewish experience through song and dance, making it more palatable to the American audience. This original intention is absent in Shechter’s work, and for this reason his new choreography gives the play a deeper feeling of authenticity.

“The show does have very American Jewish sensibility,” said Schechter in an interview last December. “It appeals to a rootlessness many Americans feel and a longing for the past and a simpler time. My connection to Jewish culture is different. The folk dance movement is a part of me, but as an Israeli living in London I relate to the feeling of longing. The longing for a place and tribe.”

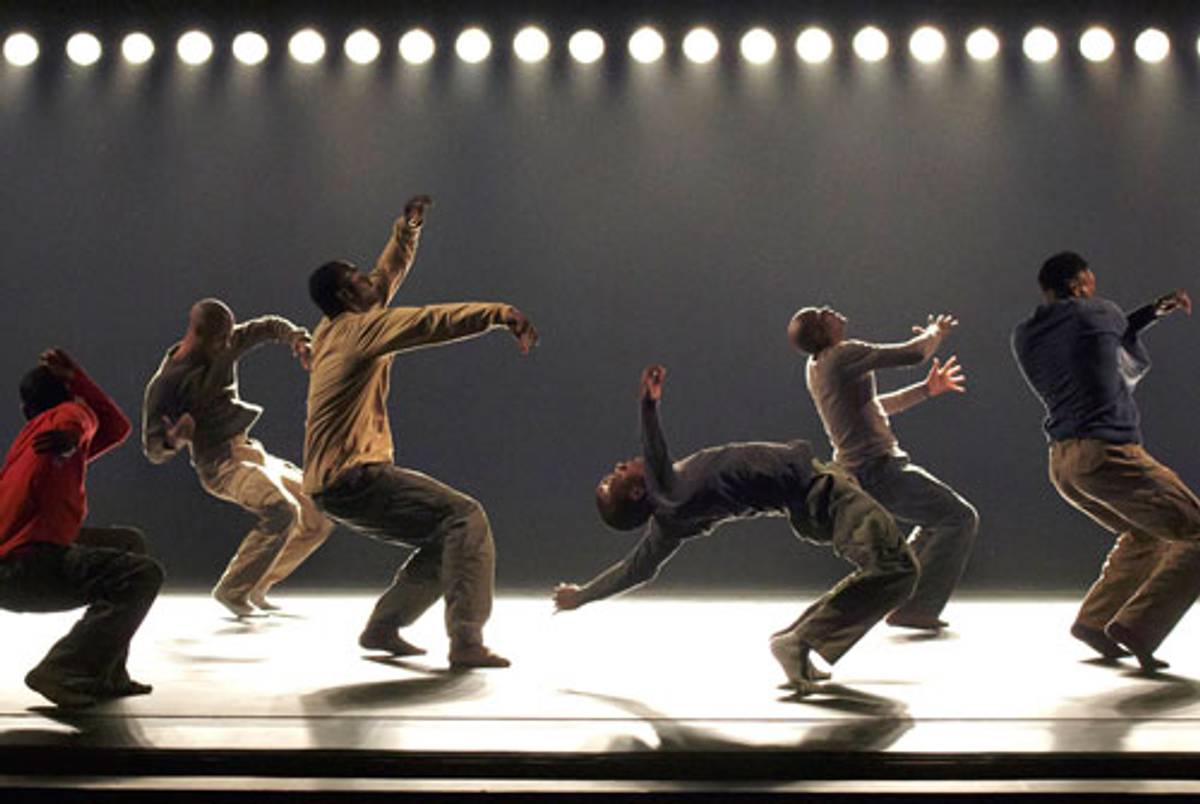

Pretty and palatable are not part of Shechter’s vocabulary. Beginning his dance training in Jerusalem with folk dance and then continuing to emerge first as a dancer with Israel’s Batsheva Dance Company and then as a musician in Paris at the Agostiny College of Rhythm, Shechter makes work that explores conflict and chaos. One of his most well-known pieces, Uprising, was performed recently by the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater during their December season at New York’s City Center.

Set with dark gray lights and smoke effects, this version was staged with seven men portraying the order of the tribe and the fight to be the last man standing. Moments of quiet and stillness were interspersed with staged violence, crawling on the ground, and pounding fists in the air.

His next project, Separate Ways, a half-evening work for the exquisite avant-garde dance group Nederlands Dance Theater due to premiere in The Hague April 28, is a project that brings him back to the world of modern dance. Shechter, like Christopher Wheeldon, the director and choreographer of the current production of An American in Paris, is part of a new wave of choreographers creating dance for Broadway. While focused on new commissions and creations for his London-based dance company, Shechter is excited by the possibility of future collaborations in theater. “I’m not restricted by genre. If the work is interesting, whether it be dance, film, theater, I’ll be there.”

***

To read more of Tablet magazine’s coverage of modern dance, click here.

Stacey Menchel Kussell is a culture writer who frequently covers Israeli contemporary dance.