Maurice Sendak was 15 years old in the summer of 1943, when he first took on Peter and the Wolf, sketching the characters from Sergei Prokofiev‘s orchestral fairy tale to “ward off the boredom of the long vacation and to teach himself something about illustration,” according to Sendak’s biographer, Selma Lanes. And after working with Tony Kushner to adapt Brundibar, Hans Krasa’s opera performed by child inmates at the Terezin concentration camp, Sendak feels the opportunity to again reimagine Peter couldn’t have come at a better time.

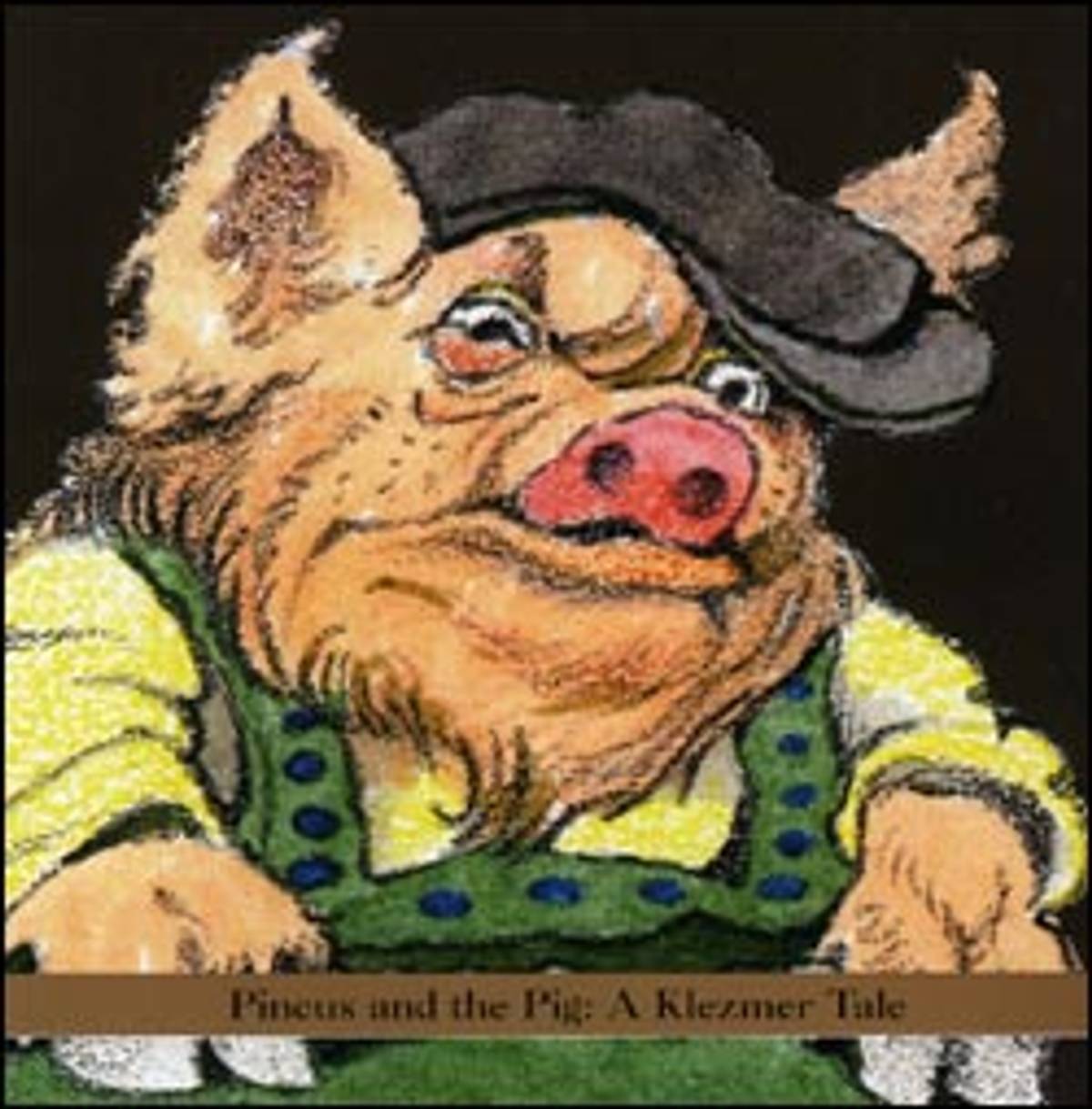

“Brundibar almost suffocated me,” says Sendak, who created the storyline and illustrations for Pincus and the Pig: A Klezmer Tale, a collaboration with the Shirim Klezmer Orchestra that will be peformed next year in Miami and New York. “Pincus is one of the very few things I’ve done involving the shtetl culture that is totally devoid of sorrow or heavy, built-in grief.”

On the CD, which also includes Shirim’s reworkings of selections by Rimsky-Korsakov, Mahler, and Satie, Sendak narrates in what he calls a “memory imitation” of the voice of his late father, whose childhood name was Pincus. “My parents only spoke Yiddish and some critical English words,” he says. “Yiddish, some Polish, some Russian. It was a grab-bag language. Those words float up to my head like flotsam and jetsam, and I’m so grateful when they do.”

When Sendak wrote Pierre, the book ended with the hungry lion eating his hero. “It satisfied me, but it horrified the publisher, who said, ‘We don’t want to scare the dear, darling children.’” Back in 1962, Sendak didn’t have the clout to prevail, so in the book the lion disgorges the boy.

“That’s what’s wrong with this country,” Sendak fumes. “We’re all the time pretending, pretending, pretending. Children live with ambiguity—especially children living now, wondering whether two more towers are going to blow up. Sometimes, there ain’t no happy ending.”

In Prokofiev, Sendak discovered a kindred soul: in Peter (and Pincus), the duck is swallowed alive. At the same time, Pincus is a story of triumph. “I was happy it was about not hurting to be a Jew, not hurting to tell a story that had pain in it. In fact where we win, how ’bout that? We win!”