The words Holocaust and graphic novel generally bring to mind Art Spiegelman and his trailblazing, Pulitzer Prize-winning work Maus, which got its start as a three-page comic in 1971. Fifteen years later it was published in book form, paving the way for an unlikely new genre. In the more than two decades since the publication of the granddaddy of Holocaust graphic novels, Anne Frank’s diary has been published in comics form; the story of the Warsaw Ghetto has been turned into a graphic novel, and other children of survivors have embraced the genre to recount their families’ histories—pointing to the fact that, tragically, Spiegelman’s father wasn’t the only one to “bleed history” (to borrow a phrase from the subtitle of Maus).

With two recent publications, Israel has further embraced the form of the Holocaust-related graphic novel: The first is Michel Kichka’s memoir Second Generation: Things I Never Told My Father, which was originally released in French and, like Maus, recounts growing up in the shadow of a Holocaust survivor. The second is Rutu Modan’s The Property, a fictional account of a young Israeli woman and her grandmother who travel to Poland to reclaim an apartment belonging to the family before the war, published simultaneously in Hebrew and English.

At first, these two works appear to be united solely by the fact that they both fall into the “Holocaust graphic novel” category—one is autobiographical, the other is fictional; one is drawn in stark black and white, the other bursts with vibrant color. Yet while profoundly different in narrative and graphic style, Second Generation and The Property have more in common than meets the eye: Both center on family bonds, secrets, and intrigue; both feature journeys to reclaim something tangible or intangible that was lost; both are characterized by a bittersweet intensity and off-kilter humor.

Kichka opens Second Generation with the line, “My father almost never spoke about his family.” The panel underneath it shows the author, as a child, looking at the tattoo on his father’s arm and wondering, “Who wrote a number under his arm hair?” The book’s first two chapters focus on Kichka’s early curiosity about his father’s wartime experiences, blending well-known Holocaust imagery with his father’s personal story of survival.

Kichka’s father, Henri, made only passing references to his life during the war—whether joking about how his wife’s soup reminded him of Auschwitz because he never ate soup like that there, or lamenting how the Nazis destroyed his feet by forcing him to march in the snow.

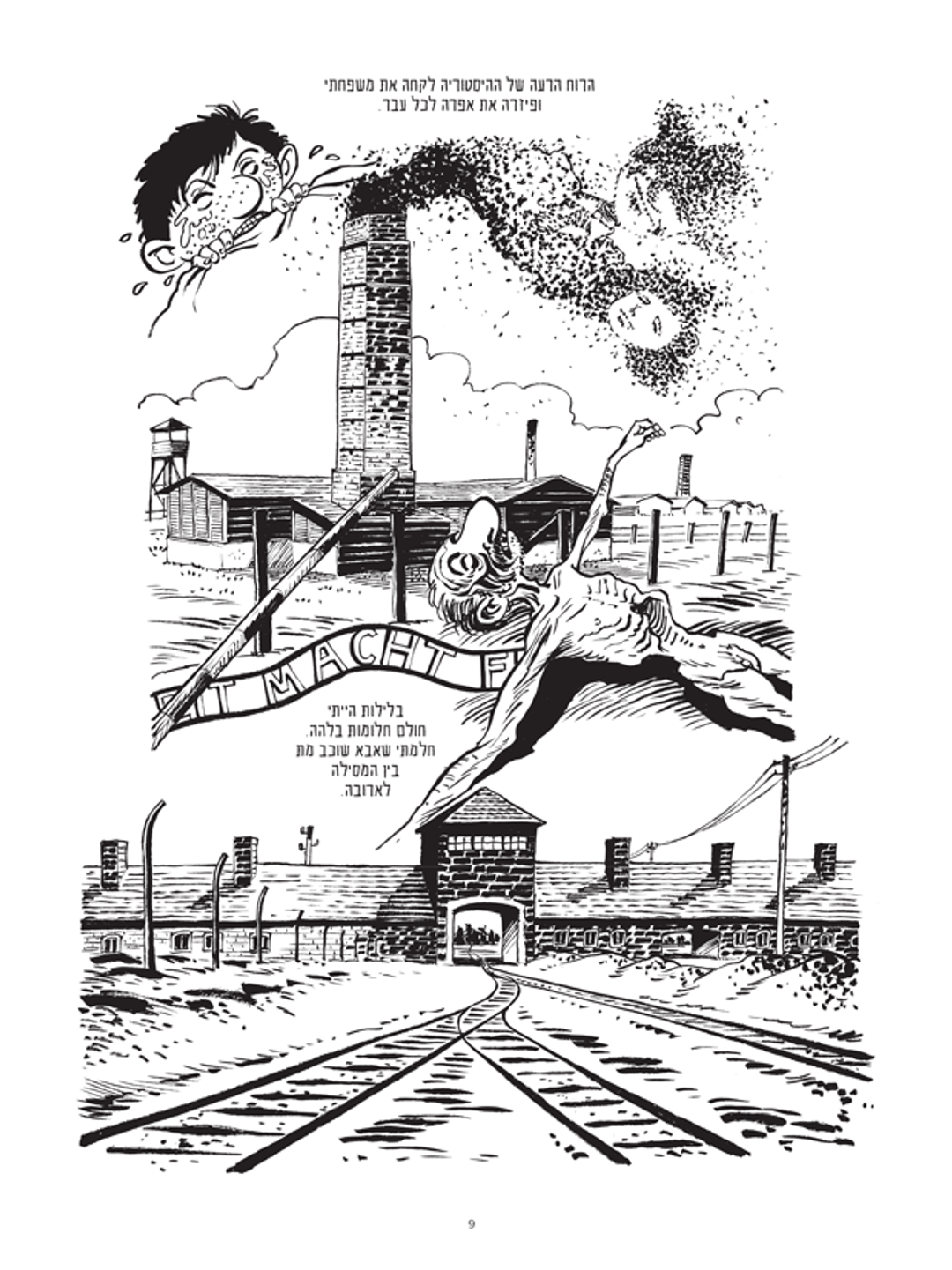

As a child, Kichka searched for his father, to no avail, in the haunting photograph of emaciated survivors lining barracks in Buchenwald on the day the camp was liberated. He writes how he felt like “that boy,” drawing himself as the Jewish youth holding his hands up in the iconic photo from the Warsaw Ghetto. He depicts his childhood nightmares using a combination of his father’s gaunt, naked corpse, the Arbeit Macht Frei sign, railroad tracks, and a crematorium scattering his family’s ashes to the wind. At the top left corner, Kichka appears as a crying, frightened child hiding under the covers.

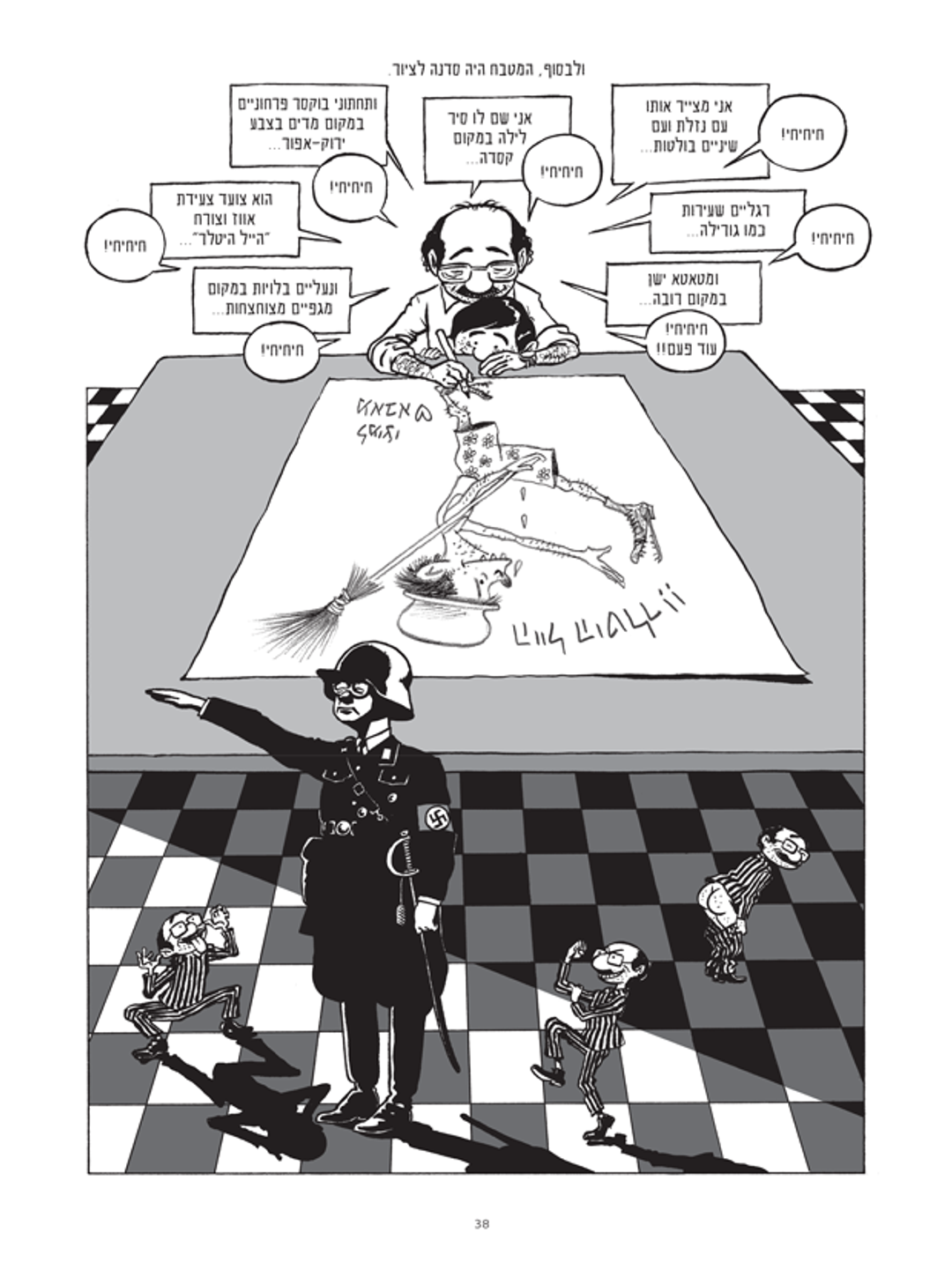

Yet the war featured in some of Kichka’s more pleasant recollections as well. In describing how he inherited his love of drawing from his father, Kichka depicts himself as a child, sitting on his father’s lap while he draws Hitler—with a runny nose and buckteeth, wearing flowered boxer shorts and carrying a broom instead of a rifle. On the same page, below that memory, Kichka depicts a black-clad Nazi surrounded by three drawings of his father: One is mooning the Nazi, one is giving him a bras d’honneur, and one is sticking out his tongue. You can almost hear him say, “I survived Auschwitz—na-na-na-na-na.”

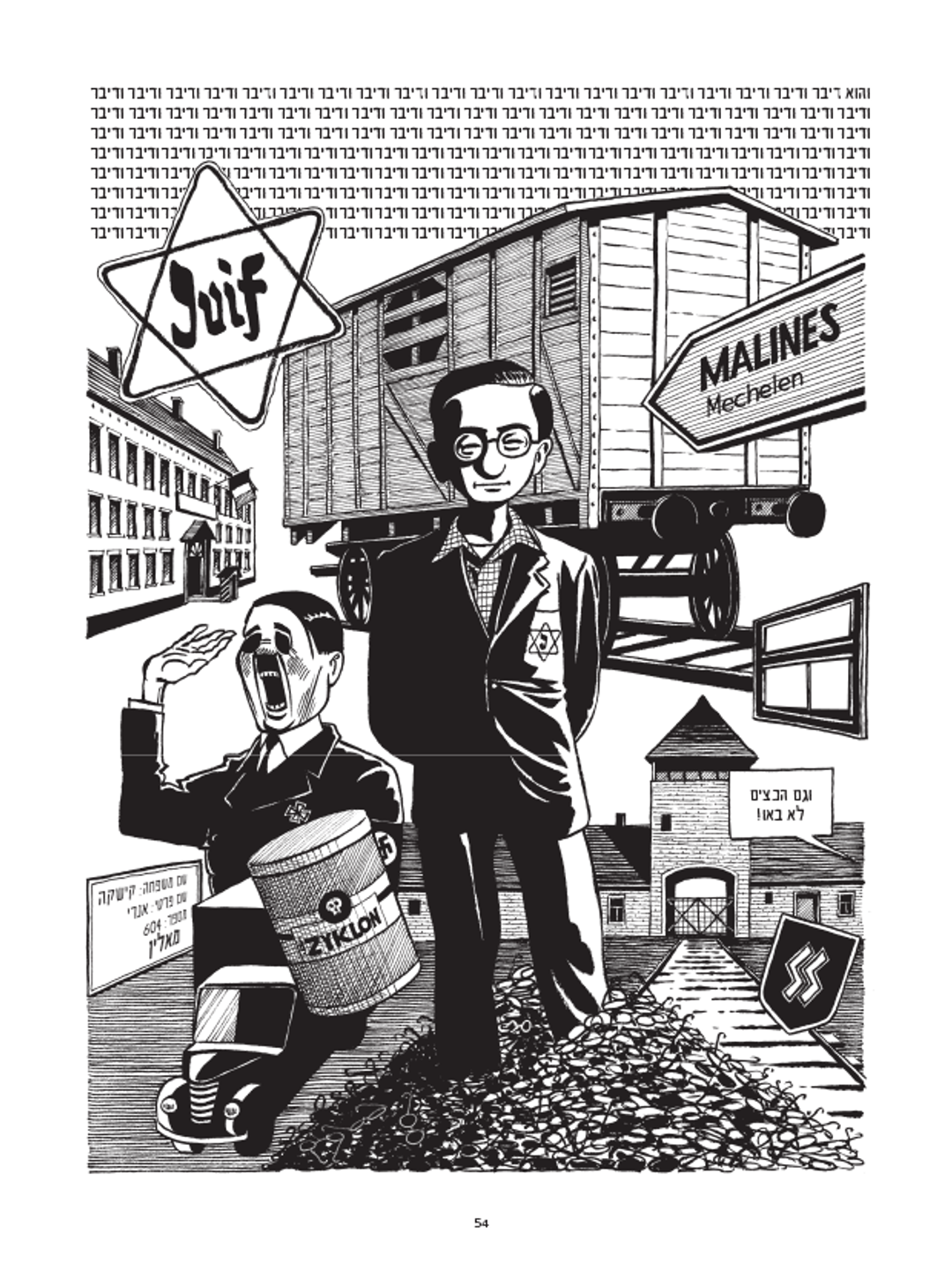

The book’s turning point comes about midway, when (spoiler alert) Kichka’s younger brother, Charlie—whom he describes as the spitting image of their father—commits suicide, and he returns from Israel to Belgium to grieve with his family. On the first evening of the shiva, as the last guests remain, Kichka’s father abruptly says, “On Sept. 3, 1942, the Gestapo arrested us,” while on the next page Kichka tells us, “and he talked and talked and talked and talked and talked,” repeating the Hebrew word for “and talked” more than 100 times. On the same page, he portrays his father as a young man standing next to Hitler, with a yellow Star of David, a cattle car, a canister of Zyklon B, and other Holocaust symbols.

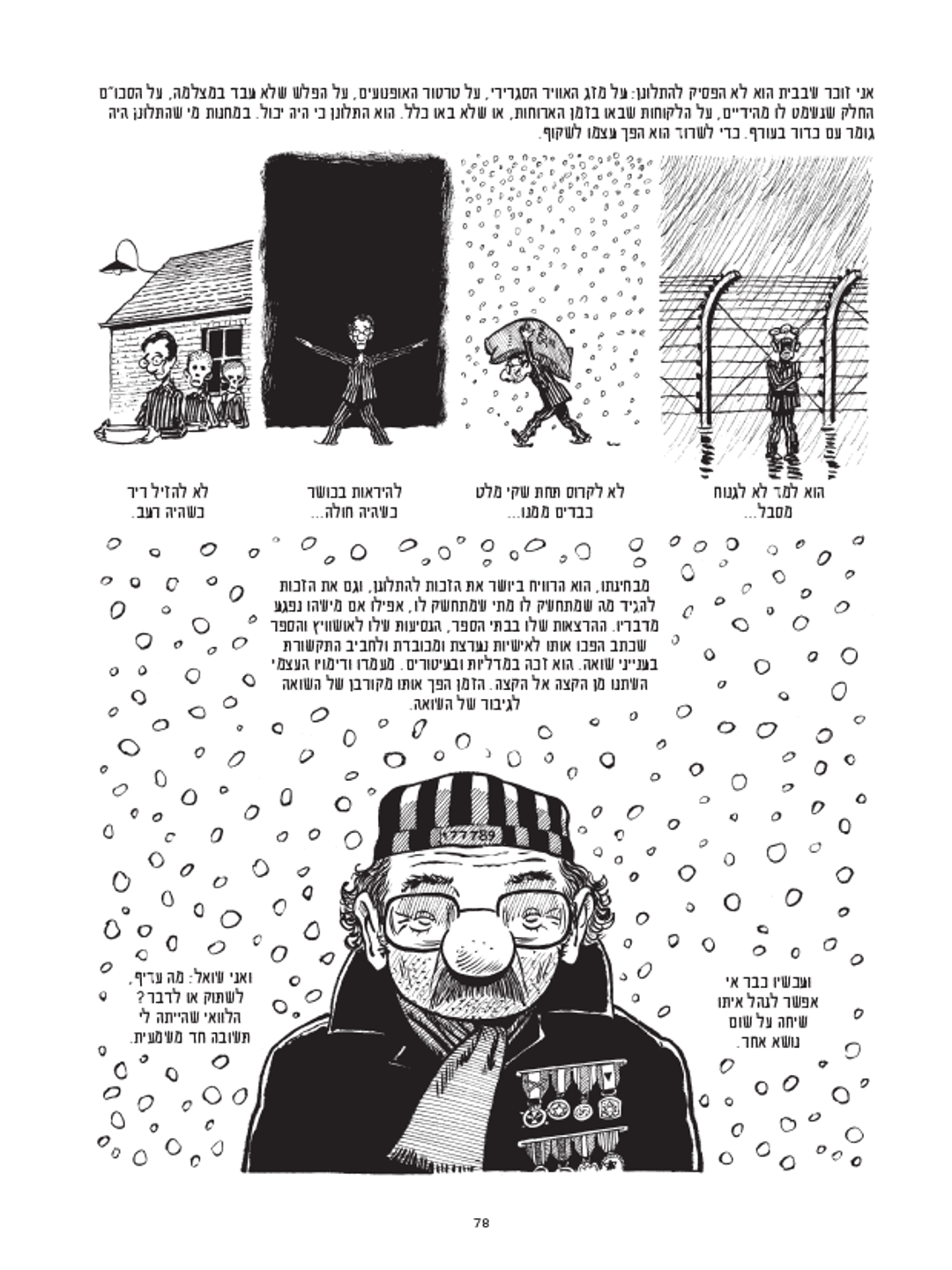

“Suddenly I understood that, for the first time in his life, my father is telling his Holocaust story,” Kichka writes. “But I came to mourn my brother, to talk about him. Instead, Dad is talking about himself, and I can’t bear to hear it. I stand on the sidelines rather than sit down with everyone and whisper to myself, ‘What shitty timing!’ ”

From that moment on, Kichka said, his father began sharing his story at Belgian schools, joining high-school trips to Auschwitz, reliving his past and even writing a book about his lost youth. “Time transformed him from a victim of the Holocaust to a Holocaust hero,” Kichka writes. “And now you can’t talk to him about anything else. So, I wonder: What’s better, to keep quiet or to talk? I wish I had an unequivocal answer.”

Perhaps there is a happy medium, Rutu Modan seems to suggest in her latest graphic novel, The Property. Loosely based on her personal experience of meeting her estranged maternal grandfather, the book opens with an epigraph attributed to Modan’s mother: “With family, you don’t have to tell the whole truth and it’s not considered lying.”

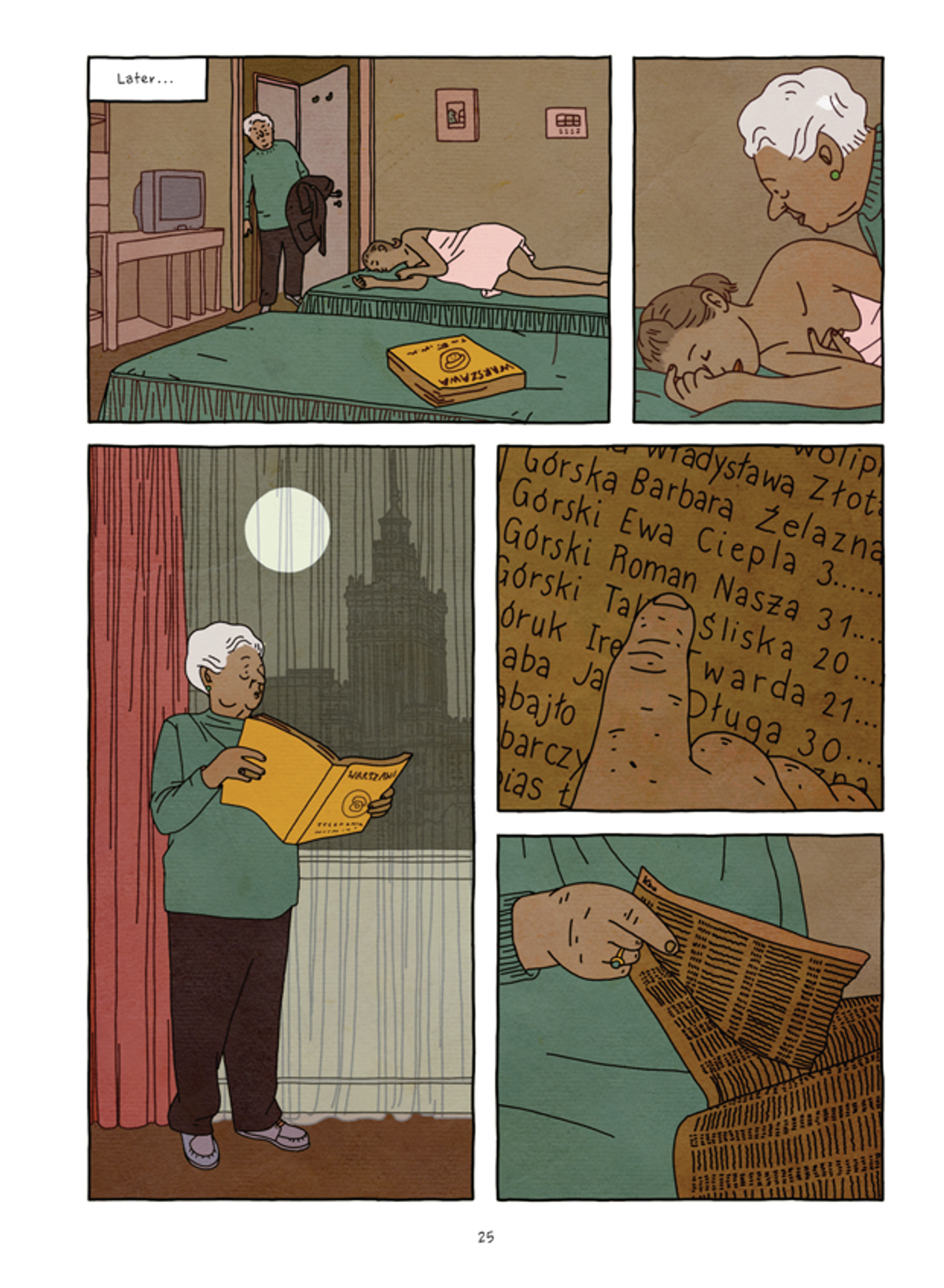

That sentence sets the stage for the fictional story of Regina Segal and her granddaughter Mica to unfold, as the two feisty women travel from Israel to Warsaw ostensibly to deal with prewar property issues. Soon enough, the seemingly straightforward plot thickens into a yarn that’s part love story, part whodunit, part screwball comedy, and part exploration of Jewish-Israeli identity. Modan even uses different typefaces for the different languages—Hebrew, Polish, and English—spoken throughout the novel, adding a graphic element to the drama.

Modan has a knack for using small stories about interpersonal relationships to explore bigger issues: Her first full-length graphic novel, Exit Wounds (2008), delved into complicated life in contemporary Israel, in a tale about a taxi driver who gets a call telling him his estranged father was killed in a suicide bombing. The Property also taps into the zeitgeist of modern-day Israel, where the Holocaust is a perpetual undercurrent and where ever more Israelis embark on “roots trips” across Europe to reconnect with their family histories and, in some cases, recover lost assets.

From the start, Modan depicts the ambivalence that sometimes accompanies such trips. On the plane to Poland, when a guide accompanying Israeli students on a March of the Living trip tells Regina how moving it is to be able to show Mica her old haunts, she responds, “Warsaw doesn’t interest me. It’s one big cemetery,” adding that they’re going simply to claim their property.

Once in Warsaw, however, Regina’s true motives for the trip emerge, as she stealthily tracks down an old love interest—a non-Jewish Pole named Roman Gorski who (spoiler alert) fathered her son, Mica’s late father, before Regina fled to Mandatory Palestine to escape the Nazis. Mica, meanwhile, treks all over Warsaw in search of the lost property; she is alternately accompanied by a gentile tour guide of Jewish Warsaw, with whom she becomes involved, and shadowed by a family acquaintance driven by his own motives.

Unlike Kichka, Modan doesn’t explicitly depict Holocaust imagery in The Property. Instead, her clear drawing style, which is often compared to that of Hergé’s Tintin books, switches from vividly colored panels to sepia-toned ones when characters discuss the past or flash back to it. The only Nazis pictured in the book appear when Mica inadvertently gets “caught” in a reenactment of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and is rescued by the wily family friend.

Fittingly, the action comes to a head as all the characters unite in a Warsaw cemetery on Zaduszki (All Saint’s Day), the day that souls of the dead return to visit their homes, according to Polish tradition. This not only echoes Regina’s remark about Poland being one big cemetery—it also underscores the fact that family skeletons often have a way of creeping back to life despite painstaking efforts to keep them buried.

Anat Rosenberg is a New York-based editor and writer.