American ‘Auschwitz’

A late-1970s surge in interest in the Holocaust coincided with a new ‘survivor’ mentality found in unexpected places, including Detroit and the Bee Gees

In the early 1980s, I worked as a psychotherapist in Wyandotte, Michigan, a town in the Downriver area south of Detroit. Like the famous River Rouge, most Downriver communities were built around auto plants, steel mills, and related heavy industry. Between the end of the Second World War and the mid-1970s, life was generally predictable. Most workers expected to have their jobs for as long as they chose, rising with seniority in rank and reward. The work itself was often bone-breaking, but pay and benefits were good thanks to union contracts. Many employees called Ford “Ford’s”—as though they were part of a large family business. Above all, the mills were the center of social and cultural affiliations—clubs and leagues, parades and picnics—which stitched together “the life” even if one worked elsewhere.

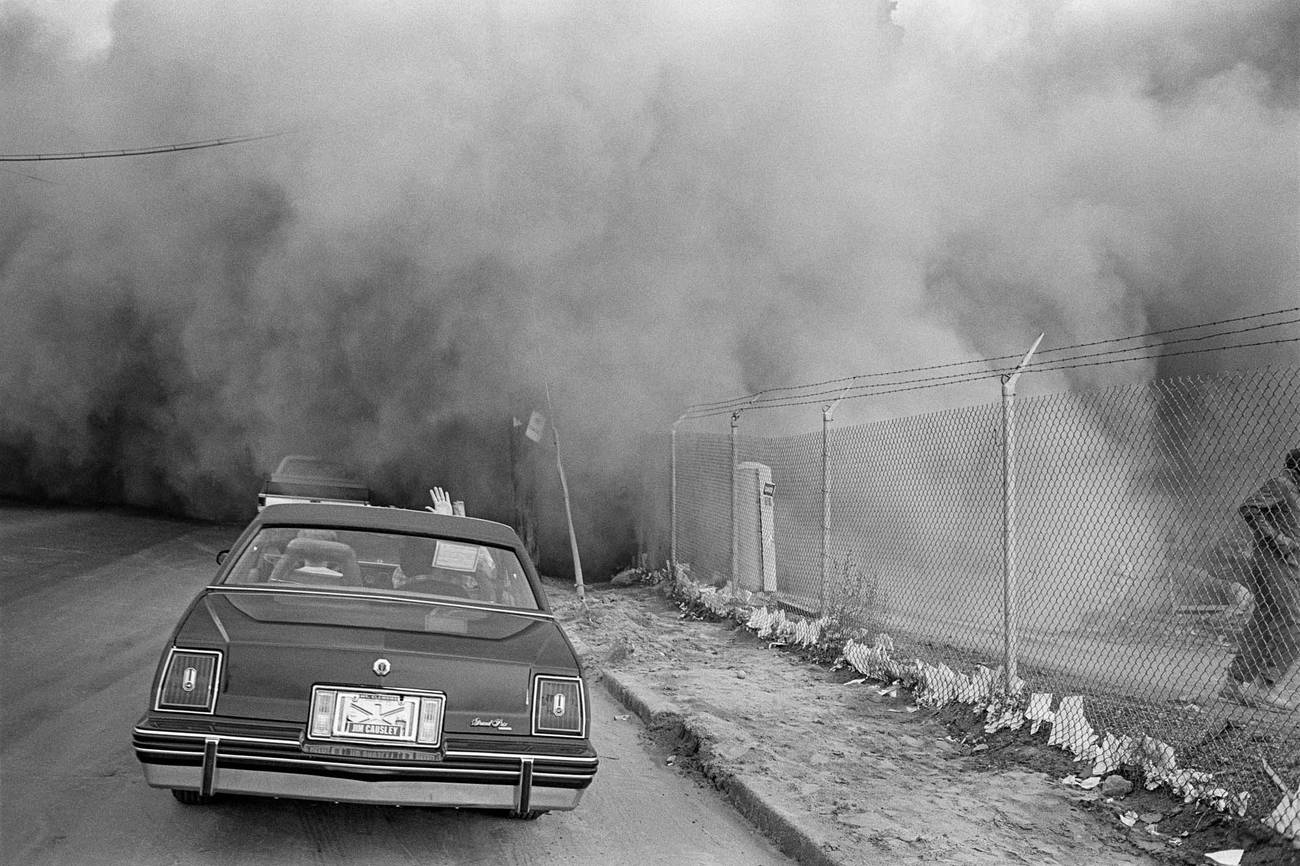

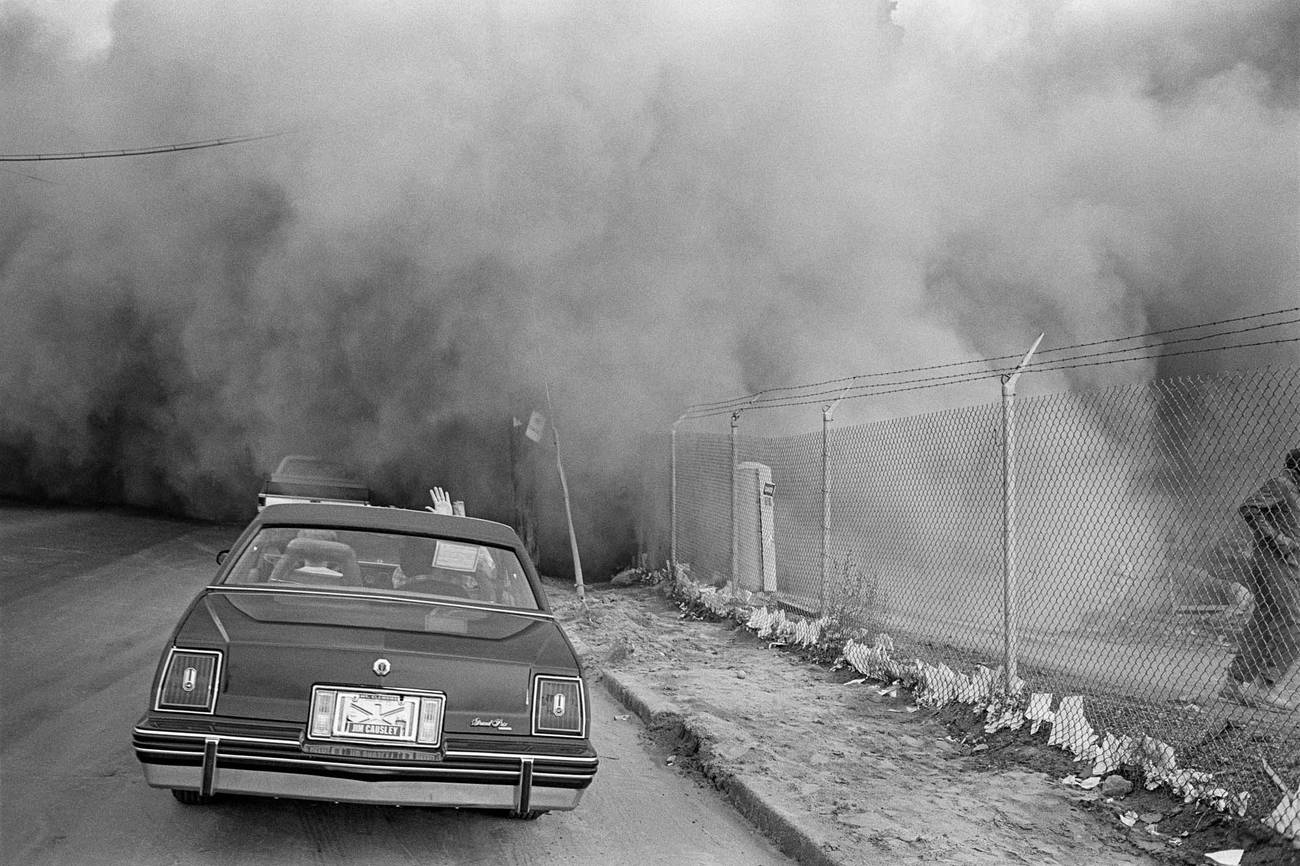

Beginning in the middle and especially late 1970s, “the life” began to unravel. Plants, or large parts of them, shut down. For most workers, their jobs, along with the factory itself, were gone forever. The loss of jobs went beyond the loss of jobs. People lost touch with each other; marriages frayed or broke; suicides, drug, and alcohol abuse rose—exponentially. The communal one-liner was “Last one out of Michigan turn off the lights.”

One of my patients was a smart, young chemical worker who still had his job, although its demands were increasingly onerous. Part of the day, he worked suspended over a toxic pool, barely able to breathe. He had just changed shifts in the hope of getting better work. One day, at the end of our session, he remarked, “So now I go back to Auschwitz.”

It is a certainty my patient was not aware of my own Holocaust scholarship. He didn’t need to be. His plant was BASF, a German-owned chemical company. Along with the drug manufacturers Bayer and Hoechst—and a group of smaller companies—BASF formed the conglomerate I.G. Farben in the 1920s. In collaboration with the SS, Farben ran Buna/Monowitz, the industrial slave labor camp at Auschwitz.

I don’t know how much my patient knew about BASF’s Auschwitz past; we never discussed it. Either way, by the early 1980s, Holocaust images were in the American air, and the Holocaust had become a trope for disasters more generally. Raul Hilberg, the “Dean” of Holocaust historians, noted that the surge of both scholarly and popular interest began suddenly in the late 1970s. “Here, in the United States, something happened. We can almost pinpoint when. It was roughly 1978. … Here we see the multiplication of books about the Holocaust, of courses about the Holocaust, of curricula about the Holocaust, of conferences about the Holocaust.” Focusing on feature films, historian David Wyman noted that “from 1962 until 1978, Hollywood made almost no films directly related to the Holocaust.” From 1978 onward there was a steady stream of American film and television productions about the genocide. The Holocaust became central in American apocalyptic iconography.

No one can say with certainty how widely the Holocaust played in Rust Belt imagination during the catastrophes of late ’70s and ’80s. But rhetoric of battlefields, bombings, and survivors was ubiquitous, including images of the Holocaust, in commentary on the economic meltdown. The Museum of Industry and Labor in Youngstown, Ohio—also known as Youngstown’s “Steel Museum”—was described by a reporter in the 1990s as “our Holocaust museum.” He elaborated:

A large part of it [the museum] evokes horror and shock and loss that the Valley must have felt beginning in 1977. … Watching those blast furnaces get torn down must have been like staring in disbelief as someone bursts into the living room, carts off all the furniture and then leaves you, stunned and helpless and alone, in the middle of the floor. You wonder how you can get on with life after experiencing such devastation.

Obviously, pillaging a living room, or even a whole community of living rooms, is not genocidal extermination. But the point is the role that the Holocaust had come to play in everyday American imagination—one of a cluster of images that stood for the end of a world.

When a plant goes down, it takes everybody with it. During the time I worked in Wyandotte, I saw plenty of managers as well as blue-collar workers lose their jobs. But the big hit to white-collar workers came in the ’90s with the wave of “downsizing” in major corporations. In 1993, IBM laid off 60,000 people, essentially overnight. There was no precedent in postwar American life for such mass dismissals. Other large companies soon followed suit. As with the plant shutdowns of the ’70s and ’80s, it was clear that these jobs would not be coming back.

We have become so accustomed to contingency in employment, as in other spheres of American life, that it is now hard to imagine the expectations that were shattered by becoming abruptly disposable. As The New York Times put it, “the notion of lifetime employment has come to seem as dated as soda jerks, or tail fins.” But, as in Downriver, lifetime employment was precisely what was assumed. That one could work hard and work well and work loyally over decades—and then be discarded—was unthinkable.

Like my BASF patient, the “survivors,” who called themselves that, did not necessarily have it easier. The Times quoted the diary of an executive secretary who wanted to remain anonymous:

Entry: Every day I have lunch with my friend G. … We will probably not see each other again …

Entry: My boss left last month. There’s no one left to report to.

Entry: I ran into B today. He wasn’t offered a job and is devastated. Any sense of joy I had at being on the ‘Schindler’s list’ of employees who’ve got jobs with our new parent corporation has been wiped out by experiences like this.

Entirely private, these entries, including Schindler’s List, obviously have nothing to do with the public assertions of victimhood with which Holocaust invocation is sometimes associated. They are about loss, pure and simple.

There are many analyses of the changes in the U.S. economy that began in the 1970s. The key here is that the change was foundational. In the ’90s, a Chase CEO spoke of the “seismic transition” in American economic life. “Since 1985 we’ve been going through a secular change as great as the Industrial Revolution. And we don’t know how it will turn out.” Many Americans believed it would not “turn out”—at least not for themselves or their children. The change was systemic, going far beyond the impact of particular events like Watergate or the fall of Saigon. The titles of the most cited histories of the ’70s—Pivotal Decade, The Great Shift, The Age of Fracture, Stayin’ Alive, Something Happened—suggest the tale.

The Holocaust had come to play a role in everyday American imagination—one of a cluster of images that stood for the end of a world.

What happened? The most sensitive writers describe both loss and being lost. Thus, Philip Roth said of the period: “Everything now is ‘was.’ The old system that made order doesn’t work anymore. All that was left was … fear and astonishment … now concealed by nothing.” “Stayin’ Alive,” the disco anthem of 1977, is mainly remembered for John Travolta’s strut in Saturday Night Fever. But the song ends: “Life goin’ nowhere/Somebody help me/Somebody help me, yeah/Life goin’ nowhere/Somebody help me, yeah/I’m stayin alive.” The lyric is repeated eight times; in the music video, set within a landscape of rubble and ruin. “Stayin’ Alive” is obviously not about swagger. It is about surviving.

Beginning in the mid-1970s, images of “survival” and “survivors” emerged everywhere in American culture. Concepts that originated in serious work with victims of violence—including genocide, torture, and rape—became signatures of the times. As Christopher Lasch was the first to describe, everyday coping as much as life and death struggle was suddenly portrayed as “survival.” Applied so broadly, the rhetoric of extremity served both to express a persistent sense of crisis and, by ironic overstatement, to dilute it. Either way, the sense of underlying apprehension remained.

In 1979, The New Yorker published a cartoon depicting two men marooned on a desert island, one palm tree between them. The caption has one saying to the other: “That’s what we are all right—survivors! People will say, ‘Hey, those two are real survivors! Talk about survivors—look at those two!’ Yes sirreee, no doubt about it, when it comes to survivors, we really …” That The New Yorker published the cartoon is proof enough that readers would get the joke: Identifying as a “survivor”—and wanting to be known as a “real survivor”—had become ubiquitous.

However hyped, being a “survivor” is a minimalist aspiration, a constriction of hope and horizon. Stayin’ alive is what you hope for when economic, cultural, and political life discourage hoping for much else. As Lasch summarized: “The hope that political action will gradually humanize industrial society has given way to a determination to survive the general wreckage.”

Understanding the survivalist turn in American culture in the context of pivotal changes in American economic and political life is essential to understanding the surge in Holocaust invocation in the same period, and especially a new fascination with Holocaust survivors. The change was not one-directional. As Lasch notes, images of mass death already prevalent—whether from the Holocaust, nuclear war, or predicted environmental catastrophe—themselves contributed to a rhetoric of extremity. At the same time, in an age that had its own reasons for loss and foreboding, the temptation “to reinterpret every kind of adversity in light of Auschwitz proved almost irresistible.” The 1978 NBC miniseries Holocaust both reflected and catalyzed the explosion of Holocaust invocation at the time. Based on survey research conducted after the broadcast—watched by an extraordinary 60% of Americans—sociologist Robert Wuthrow concluded that the Holocaust had become both “a symbol of contemporary chaos” and a sign of how bad things could get. Imagining the Holocaust was a way of “touching bottom”: One was not entirely in the dark about what was in the dark.

Ironically, perhaps, the ways Americans imagined Holocaust survivors served to mitigate the ways they imagined the Holocaust itself. Holocaust survivors were “real survivors”—apex survivors—and they were so appropriated. Hardcore survivalists prepping for social meltdown became obsessed with the Jewish armed resistance. Partisans not only had guns but also knew woodcraft, folk medicine, and how to build bunkers. One survivalist popular on YouTube recommended the video, “Resistance: Untold Stories of the Jewish Partisans.” She reported a “TON of requests.”

Holocaust survivors are featured in everyday “survival guides,” especially those that focus on “resilience” and a field that calls itself “survival psychology.” Holocaust survivors’ own responses have been various. In recent years, some have published “how to survive” self-help books, reprising the Victor Frankl tradition. Earlier on, many were more reticent. In the early 1980s, for example, Sally Grubman, a survivor of Auschwitz and Ravensbruck, reflected:

There is a tremendous interest in the Holocaust that we didn’t see when we came … but also some confusion about the reality. … We are not heroes. We survived by some fluke that we do not ourselves understand. And people have said, “Sally, tell the children about the joy of survival.” And I can see they don’t understand it at all … We went through fire and ashes and whole families were destroyed. And we are left. How can we talk about the joy of survival?

Recently, a textbook required for the UNC minicourse “21st Century Wellness” was skewered for suggesting—as a headline read—“Holocaust victims who died failed to find their inner strength.” The actual text included: “The people in the camps who did not tap into the strength that comes from their intrinsic worth succumbed to the brutality to which they were subjected.”

It is tempting to dismiss such versions of “survival psychology” as simply silly, but I believe it would be a failure of sociological imagination if we stopped there. Both survival psychology and apocalyptic survivalism tell us very little about the Holocaust or its victims (including survivors). But they do suggest some of what is darkest in our own time. Becoming abruptly disposable, the loss of ways of life, the erosion of predictability, the devaluation of craft and commitment in favor of “survival” have at least a thematic affinity with popular Holocaust representations—as the reporter in Youngstown tried to suggest.

It is also true that such invocation collapses distinctions between widespread loss on one side and mass murder on the other. Such rhetorical meltdown may itself reflect wider meltdown in the ways we denote crisis since the ’70s. Little bad happens anymore that is not described as “trauma” requiring “survival.”

In the mid-’80s, Robert Bellah asked: “Is it possible that we could become citizens again and together seek the common good in the post-industrial, post-modern age?” Ironically, perhaps, it was in the wake of national catastrophe—the attacks of Sept. 11—that a new age of American citizenship was proclaimed. For a brief moment, many imagined that the fragmentation of the prior three decades would be reversed. Survivor, the television show, briefly went off the air. But even the “new reality” was quickly framed in survivalist terms. Regarding the 2003 Iraq war as Sept. 11’s sequel, Bush speechwriter David Frum wrote, “It is victory or holocaust.”

Saddam’s holocaustal threat, at least to us, turned out to be overrated. The committed American citizenship for which Bellah yearned was stirred again—at least for some—by the brief (in retrospect) era of “Yes, we can.”

The Trump era is equivocal, characterized both by survivalist flight and activist fight. A 2017 National Geographic survey found that “forty percent of Americans believed that stocking up on supplies or building a bomb shelter was a wiser investment than a 401(k).” Silicon Valley elite—the not “left behind”—are building survival bunkers in New Zealand. Recent work suggests that for many who are left behind—especially white Americans without a college degree—even surviving can be a lot to expect. The world I found Downriver in the 1980s—especially the lost solidarity once provided by union membership, social clubs, and relative predictably—has become more desperate and disengaged. Beneath cynicism or stoicism are layers of pain, shame, and barely mitigated hopelessness. The much-discussed “divisiveness” of contemporary American politics is not only about differences in policy. For many, it is about whether politics and policy are relevant at all.

This is the context in which the coronavirus pandemic emerged. The large numbers of dead, the rhetoric of war, the sense of pervasive threat, and the uncertainty of the future realistically compel a preoccupation with survival. Hardcore survivalists congratulate themselves for having seen it coming and having “prepped” accordingly. Protesters of lockdowns invoke the image of “compliant” Jews who “went like sheep.” A Kansas newspaper featured an anti-lockdown cartoon captioned, “Put on your mask and step into the cattle car.”

Far more gently, there is the surge in “survival psychology” in which Holocaust survivors are commonly featured. The host of “Resilience During Challenging Times,” an online series of interviews with survivors, reflects: “I thought we could all find solace and wisdom from those who survived the Holocaust, even in our own current circumstances.” In a double segment broadcast in early April, 60 Minutes featured a report on “interactive” survivor testimonies. Lesley Stahl introduced the program:

As the world struggles to contain and recover from the novel coronavirus, we offer a story we completed just before life changed so dramatically. It’s a story of history, hope, survival, and resilience which has its roots in another time when the world was convulsed by crisis, World War II.

Minutes after writing this paragraph, I received an email promoting a new film specifically on Auschwitz survivors: “In these times, we all need to see this valuable film showing us a road map to survival and finding meaning in our lives.”

Some survivors have questioned the juxtaposition, not only because of the obvious differences between targeted genocide and pandemic, but also because the emphasis on personal resilience obscures the role of pure luck—“some fluke,” as Sally Grubman put it—and the practical importance of particular relationships (useful to survival but not necessarily positive) during the destruction. Understandably, however, stories of “history, hope, survival, and resilience” are what we want to hear.

It is too early to know the wider impact of the pandemic. As after Sept. 11, some imagine genuine transformation. Our being “in it together” is not only a communitarian ideal but one that is empirically grounded in epidemiological data. Others foresee social disintegration, particularly if the death toll continues to soar, uncertainty increases, and economic collapse is severe and sustained.

In the United States, the pandemic arose in a society already riven by class division, political disunion, and cultural fragmentation. Rather than a new solidarity and commitment to the common good, this scenario anticipates, in Lasch’s phrase, ever more ferocious “determination to survive the general wreckage.” Whatever its long-term outcomes, the public health disaster—terrifying in itself—becomes the most recent unanticipated place in which Americans invoke Auschwitz, cattle cars, and Holocaust survivors as we struggle to endure our own catastrophe.

Henry Greenspan is a psychologist, oral historian, and playwright at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.