Gay, Muslim, and Jewish in Berlin

A new biography explores the life of Hugo Marcus, a gay Jew who played a key role in the establishment of Islam in Germany before fleeing from Hitler

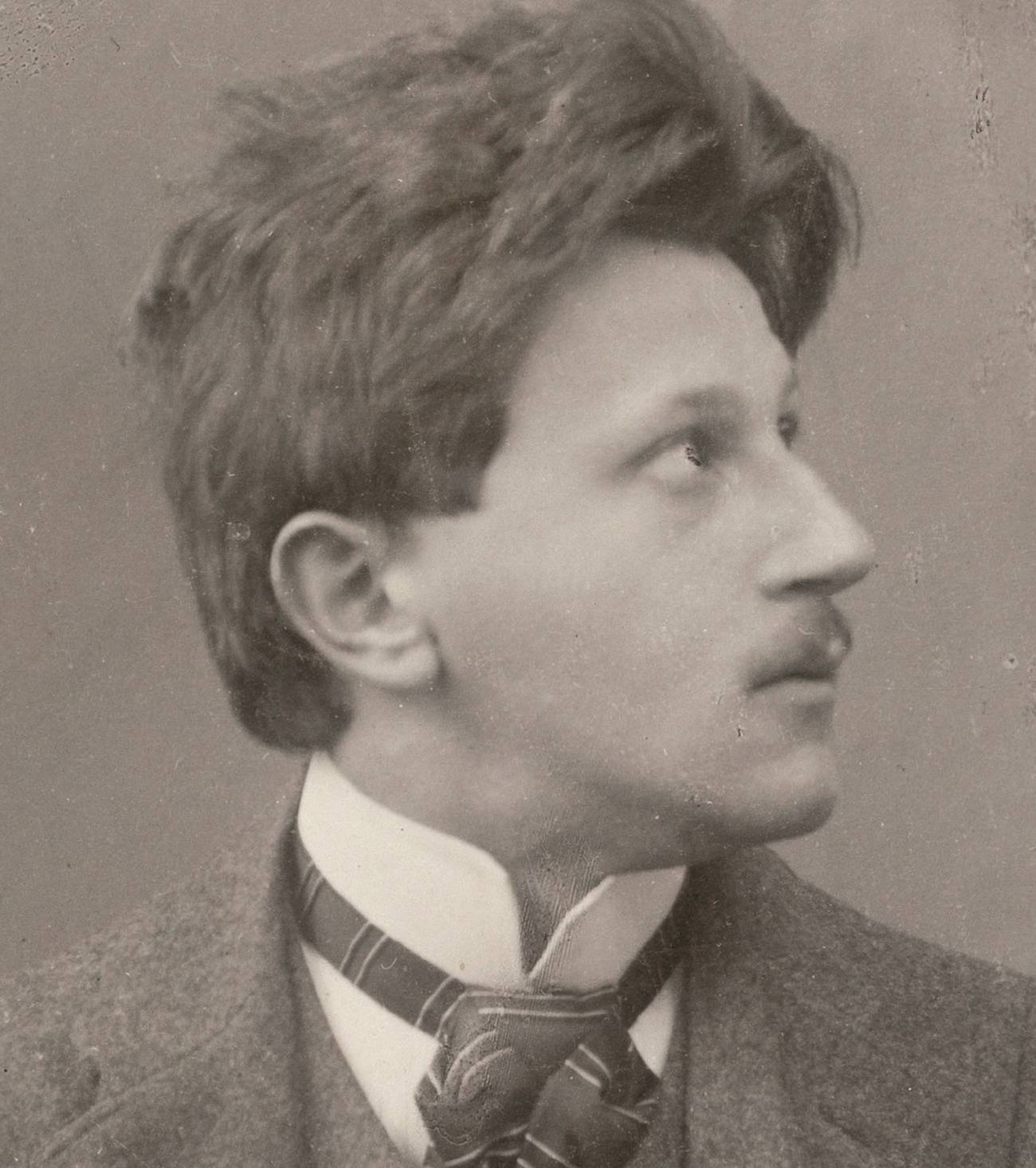

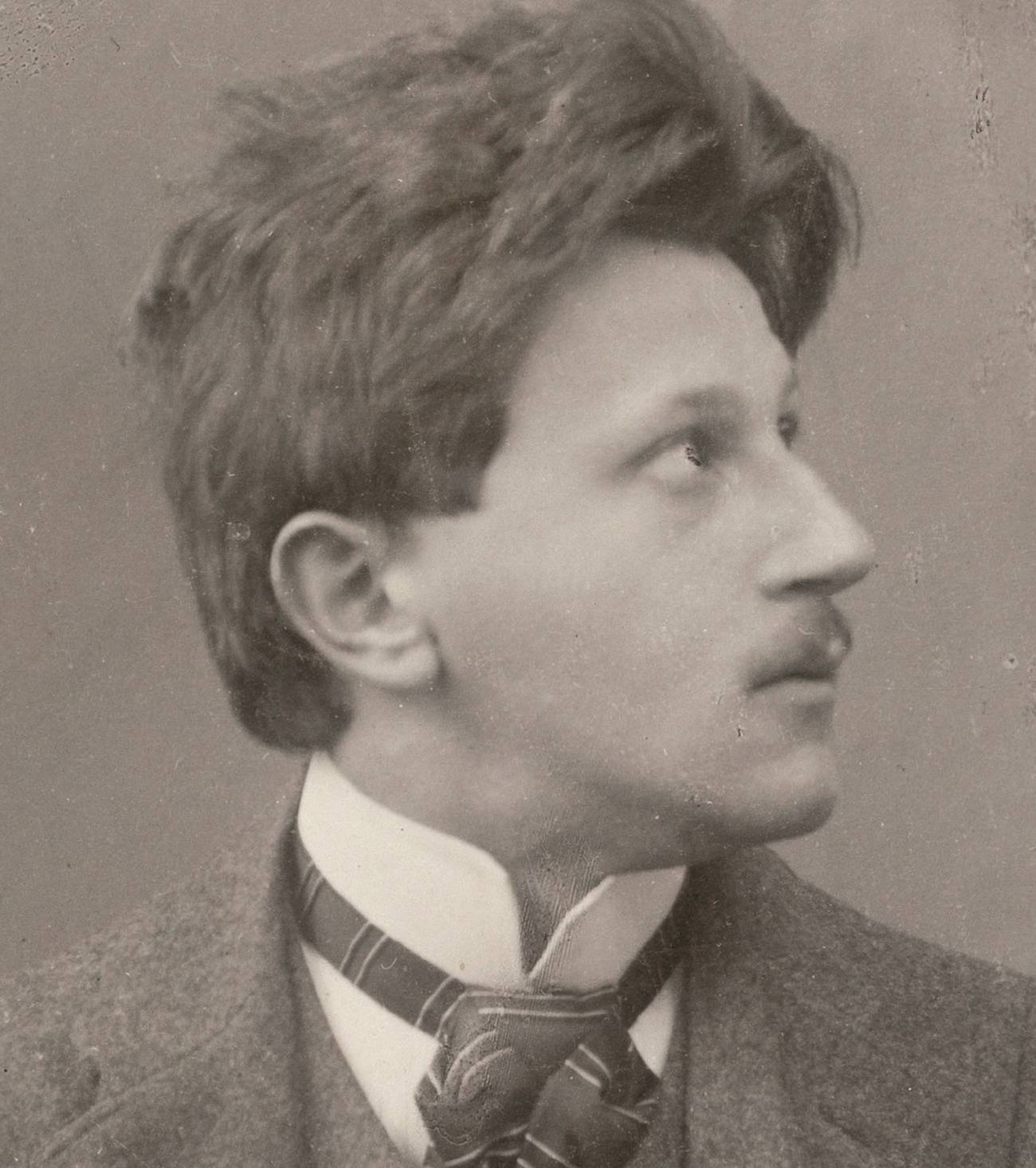

Before the Nazis came to power, the most important German Muslim was a gay Jew. In a new biography, Marc David Baer, a historian at the London School of Economics, chronicles the mostly unknown life of Hugo Marcus (1880-1966), “the only figure to have played an important role in the gay rights movement and in establishing Islam in Germany.” German, Jew, Muslim, Gay weaves Marcus’ life story into the intellectual, cultural, and political complexity of his time. Baer’s book is forensic and rich in its scholarship, as well as tender and evocative as an account of a peculiar life. He explores the instability of ideas and beliefs in time: He is highly attentive to the contingencies that shape historical moments and the interplay of the individuals and movements responding to them. In narrating the fate of daring projects of societal transformation, he shows how the astonishing era in European history through which Marcus lived enabled, and then destroyed, an immense sense of potential.

Marcus was born in Posen (which moved from Prussian to Polish control in 1919) to a “bourgeois, liberal and highly Germanized” provincial family. He was a precocious and prodigious writer. His father owned a wood finishing business (handed down from Marcus’ grandfather) and Marcus was expected, like many of his aspirational Jewish peers, to further his education before joining the family business himself. Instead, Marcus’ early adulthood was defined by moving away from family, and by moving from province to city. His complex feelings about love, place, and fellowship would soon find expression through his writing.

On a hiking trip in the Harz Mountains, as part of a movement of nationalistic singing hikers called the Wandervogel (wandering bird), a 19-year-old Marcus was “suddenly overjoyed” at the sight of the landscape. His emotions were accompanied by a rush of positive sentiment toward Germany. But he also felt “violated” by a “secret protest” which made it palpable that “as a Jew, as a cosmopolitan” he was only experiencing—could only experience—the true scope and potency of nationalism vicariously. Spring Luck (1900), Marcus’ first novella, links the status of the Jewish people to his own ideas about love and longing. The novella, a “meditation on the superiority of homosexual to heterosexual relations,” draws parallels between the perceived misfortune of heterosexual love and the relation of Jews to Israel, “which they loved like a far-away lover.” Later, as a 20-year-old doctoral student, Marcus wrote a work about “elitist, philhellenic homoeroticism” and on “pederasty, the master-discipline relationship, and a search for a new utopia.”

Following in Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s footsteps, Marcus was attracted to the “oriental” aesthetics and culture of Italy—perceived as a bridge to the possibility of gay pleasure—and went on a trip at age 21 to Capri. There, Marcus imagined the steel magnate Friedrich Albert Krupp, a guest at his hotel, as the Hadrian to his Antinous, and fantasized about serving him in exchange for Krupp successfully appealing to the Kaiser to institute a universal eight-hour work day. Krupp did in fact have relationships with younger men, but after observing this “wealthy man surrounded by a circus of ambitious, pleading artists, painters, and singers” from a shy distance, Marcus went home unsatisfied. When Krupp committed suicide a year later after being outed by Vorwärts, the social democratic newspaper, Marcus hoped that the scandal would translate into greater awareness of his “secret” cause.

Monarchist writer Hans Bluher said that the period which produced groups like the Wandervogel was characterized by “a struggle of youth against age.” In the words of Peter Gay, a historian cited by Baer, the dynamic behind youth movements in this period was that of “alienated sons [seeking] out other alienated sons”; the Wandervogel aimed to “restore primitive bonds” and form a “common existence” to “escape from the lies spawned by petty bourgeois culture” and as “a critique of the adult world.”

Marcus’ own “desire to find a utopia or to join universal brotherhoods” reflected a complicated blend of influences and experiences—some widely shared, some delicately personal. Following World War I, as Europeans searched for “a new source of guidance among the ruins of their erstwhile beliefs,” Marcus would propose Islam, as a state religion and object of mass conversion, as the solution for Germany.

Despite the startling idiosyncrasy of that project, however, Marcus partook in broader movements of change, prominently involving other Jews. Around 1901, Marcus joined the first homosexual rights organization in the world, the Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee (Scientific Humanitarian Committee). Marcus was close to the WhK co-founder and most lastingly significant member, Magnus Hirschfeld, a prophetic advocate of sexual minority rights and pioneer of modern transsexualism. Hirschfeld asserted that “no one is simply male or female; rather, “each person is characterized through a unique male-female mixture of characteristics.” In a film promoting Hirschfeld’s views, a sexologist explains that “between all opposites there are transitions, and this is also true of the sexes”; he used the term “the third sex” in reference to homosexual men and women. He coined the term “transvestite,” sought to grant transvestites medical protection from prosecution, and even supervised the first sexual reassignment operation in the world. Marcus assisted Hirschfeld in his legal efforts, accompanying him to the extraordinary Eulenburg trials of 1907-09, which concerned gay intrigue within the Kaiser’s cabinet but also addressed questions of German-Jewishness, where Hirschfeld testified as a “medical expert on homosexuality.” Marcus also served as an editor of Sexus, Hirschfeld’s journal.

In 1919, by permission of the postwar Social Democratic government, the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (Institute of Sexology) was founded to further this work. The WhK’s call for legal and institutional change aimed at protecting homosexuals and sexual minorities was intertwined with broader programs of reform that also encompassed women’s rights and pleasure: suffrage, contraception, abortion.

Like most of the gay activists of their generation, Marcus and Hirschfeld did not openly assert they were gay. Their need for personal concealment was accompanied by an outward-looking tone, “as if it were only for scientific and humanitarian reasons that they fought on behalf of the unjustly persecuted.” The WhK petitioned the German Reichstag repeatedly between 1897 and 1926 to abolish paragraph 175, a set of laws prohibiting homosexuality adopted upon German unification. Marcus assisted in crafting one of those petitions, which failed due to a lack of political majority support in the Reichstag, but which are today viewed as constituting the origins of the gay rights movement worldwide.

The aftermath of the mass murder and destruction of World War I seemed to present new possibilities for European civilization. Baer notes that in the “demand for new formulations, new interpretations, new symbols, new explanations,” and an atmosphere “marked by its iconoclasm and syncretism,” “intellectuals blended contradictory elements into blueprints for the future.” This turbulence also made itself known in matters of demographics and sexuality. Condom production and divorce and abortion numbers rose; historian Eric Weitz notes that in 1933, Germany had the lowest birth rate in Europe, half what it had been in 1900. Huge crowds greeted the likes of Theodoor Hendrik van de Velde, a Dutch physician who promoted the importance of sexual pleasure and chastised male sexual performance in marriages.

He was finally dubbed ‘Hugo Israel’ by the Nazis, who forced on him the inherited Jewish identity he sought to transcend and removed him from the country he adored but wished to change.

Berlin was home to the largest Jewish community in Germany and was the nexus of its cultural rebellions. Hirschfeld noted the “richly functional and highly diverse architecture of homoerotic desire” in Berlin, with its “multitude of tunnels, train stations, and public baths.” He described how the city offered homosexual couples “anonymity, legions of hiding places, a communal sense of like-affected individuals,” and how that moral and social freedom was undergirded by familial distance: “It was possible for native Berliners who were homosexual to continue living in Berlin and not encounter family members for over two decades.”

Meanwhile, after WWI, Muslims established their first mosques in Paris, London, and Berlin. Baer notes that while Bosnians and Tatars had lived in Germany and fought in Prussian wars, and the sight of Ottoman students and figures had been familiar in Berlin and Potsdam, the novel Muslim element in Germany following the war was “Berlin’s nondiplomatic civilian Muslim population.” These numbered between 2,000 and 3,000, an “Islamic middle class” of “businessmen, physicians, doctoral students, anticolonial activists, intellectuals and university lecturers” often sponsored by their homelands.

In the interwar period, the Berlin mosque was “crowded with men driven by the war and economic crisis” drawn from all over the Middle East and Asia. “In those days,” wrote Marcus, “there was no Islamic people that did not have its representative in Berlin”; the city was “as filled with diverse Muslims as was Mecca.” A report on the Berlin mosque’s opening ceremony described seeing Muslims of different races from all over the world “embrace one another like members of the same family.”

The two main Muslim groups in Berlin were Ahmadi and Sunni, and they competed for public recognition with the right to build and control the Berlin mosque, preaching opportunities, converts. This contest “forced the reluctant involvement of German authorities.”

The majority, however, were Ahmadi, a group who deem Indian author Mirza Ghulam Ahmad (1839-1909) to be their promised Messiah and Imam Mahdi, and are not accepted by many Sunni Muslims. The Ahmadi competed with their archenemies in the Islamic community, established by Sunni socialists who challenged the Ahmadi on religious and political grounds, to target “members of the middle class and intellectuals, who were facing severe financial and spiritual distress” for conversion. The Ahmadi appealed directly to Jews, speaking out against European nationalism and racism and promoting a vision of pansemitic harmony that combined race and religion.

Marcus encountered the Ahmadi in 1921. Their engagement with him reflects the strategy their missionaries also used in England: “Establish a mosque and a journal in the local language, win over high-profile converts, set up an organization headed by converts to propagate their vision of Islam, and translate the Qur’an into the local language.”

Marcus soon began working as the German tutor of the Ahmadis, a job which brought together his Germanness, spiritual fascinations, and homosexuality. The chance to have “multidecade relations with younger Muslim South Asian men” tapped into Marcus’ long-held desire, first outlined in his writings as a doctoral student, to pursue “idealized, intergenerational, erotic pedagogical/pederastic Greek love.” In 1923, Marcus was hired as an editor for life of all of the Ahmadi movement’s German-language publications. In 1925, he converted to Islam, becoming the only Jewish convert to and member of the Ahmadi movement in Berlin.

Marcus played “a key role in articulating the meaning of Islam for Germans, a European Islam.” He lectured at the Berlin mosque’s “Islam Evenings,” whose attendees included Thomas Mann and Herman Hesse. He played diplomat, linking “foreign Muslim dignitaries at the mosque to crowds of German guests and embassy officials from Muslim-majority lands.” One imam at the mosque said that Marcus “made our community life bloom.” But Marcus also used his platform to publicly address rising “racist-nationalist intolerance” of minorities, linking anti-colonial struggles with rising antisemitism in Germany.

Marcus’ attachment to Islam had precedents in 19th-century Jewish scholarship, whose practitioners led the study of Islam in Central Europe and had a more positive perspective on the religion than their Christian colleagues. “Jewish sensibilities,” writes Baer, including a “desire for Jewish civil equality,” “antipathy to Christianity,” and “rejection of Orthodox Judaism” led to Islamophilic interpretations of the past as well as the promotion of “a genuine Muslim-Jewish symbiosis.” The Christian history of antisemitism was contrasted with the “inter-faith utopias” of Islam, inevitably embodied by Al-Andalus and the Ottoman caliphate. This was partly founded on a conception of Islam as “rational, tolerant and philosophical” and “the religion closest to the ideals of pure monotheism first introduced by prophetic Judaism.”

The influential Hungarian scholar Ignaz Goldziher, a devout Jew, attended prayers at a mosque in Damascus in 1890, and was so deeply impressed by the religion that he “became inwardly convinced” he “was Muslim,” since Islam was “the only religion which, even in its doctrinal and official formulation, can satisfy philosophical minds.” Frankfurt-born Abraham Geiger, a key figure in the development of Reform Judaism, was deeply moved by Islam; despite not converting, he said he “believed the prophecies of Muhammad” and “termed [his] monotheism Islam.”

Marcus’ own interpretations of Islam and Germany’s unifiable potential were aligned through his “pole star”: Goethe. There is homoeroticism and Islamophilia in Goethe’s work; Baer notes, however, the exotic nature of Marcus’ perspective: “Marcus is the first and perhaps only writer to maintain that Goethe was Muslim and gay like him.”

Marcus believed in Islam as the future religion of Germany and pointed to the German past to buttress this belief. His “paradoxical utopian vision” paired Islam with “German Enlightenment culture and romanticism.” At its height, believed Marcus, Europe “got so close to Islam as almost to shake hands.” He sought to assert in particular that in the era when German Europe looked “on all humanity as a big brotherhood, just as Islam did,” none “was a better Muslim than the greatest man of those days, the German Goethe,” and therefore, “for Germans, being Muslim was to read Islam in a Goethean way.”

Unlike Muhammad Asad, another significant Jewish convert to Islam from this period, Marcus did not leave Europe and would only leave Germany by force. “Marcus never doubted that one could be German and Muslim,” writes Baer, “seeing correlations in basic approaches to life.” His actions reflected his beliefs that Islam is “compatible with German culture values and philosophy” and “rooted in Germany and German history” and that he “could live as a German Muslim, never leaving German-speaking Europe.” This was “German Islam without a Middle Eastern component.”

Marcus viewed Islam in a “Jewish way,” as a “rational and a pure expression of Jewish monotheism.” But unlike Judaism, Marcus’ Islam, founded on “homosocial bonds,” was radically inclusive. It was a “universal brotherhood that united men of all nations and races” and embracing it did not mean he needed to stop being either Jewish or German. Marcus contrasted himself with other Jews who “became Christian to escape who they were.” He did not sever formal or legal ties to Judaism and Jews, and only did so eventually in an attempt to save his life.

Adolf Hitler himself believed that the vast majority of the people who practiced Islam were racially inferior to Germans, but the Nazi dictator respected aspects of Islam. The Nazi architect Albert Speer notes in his memoirs that Hitler believed Islam’s status as a “religion that believed in spreading the faith by the sword and subjugating all nations to that faith” made it “perfectly suited to the Germanic temperament.” The Nazi party explicitly decreed in 1943 that it accepted Muslim members on the basis of equality with Christian members. As chronicled by scholar David Motadel, Himmler would cite common hatred of Jews in an attempt to rally Bosnian Muslims in the Wehrmacht and the SS.

When Marcus was incarcerated in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in 1938, it was “not as a Muslim or a gay but as a Jew.” His imam secured his release 10 days in, seeking to facilitate his travel to British India by citing a Muslim organizational sinecure. Having obtained travel documents and partly through the “assistance of his international network of gay acquaintances,” Marcus escaped to Basel, Switzerland. Both his Ahmadi network in England and India and his gay friends in Germany “remained devoted to him until the end.“

Hugo Marcus existed in the world under several names: He was known as Hamid by Muslims and Hans Alienus in the gay world. Dr. Hans Marco was how he signed his letters courting approval (and receiving little) from Thomas Mann for his utopian visions. He was finally dubbed “Hugo Israel” by the Nazis, who forced on him the inherited Jewish identity he sought to transcend and removed him from the country he adored but wished to change.

During his exile in Switzerland, letters and small publications became ways for Marcus to secure financial support and maintain ties with his scattered generation of free thinkers and a connection to his lost homeland. Der Kreis (The Circle), a Swiss gay magazine to which he contributed, is movingly described by Baer as “an island of continuity from Weimar Germany.” Aside from these distant points of contact, Marcus’ final years were quiet and isolated. He died in 1966 and was cremated in Basel, contrary to both Jewish and Muslim tradition, for reasons that will probably remain unclear.

Mardean Isaac is a writer and editor based in London. Educated at Cambridge and Oxford, he has written for publications including the Financial Times, Lapham’s Quarterly and New Lines magazine.