I’m Not There: The Art of Nathan Hilu

Nathan Hilu, an 89-year-old veteran who lives on New York’s Lower East Side, makes frenzied art from his potent memories of Jewish life and loss

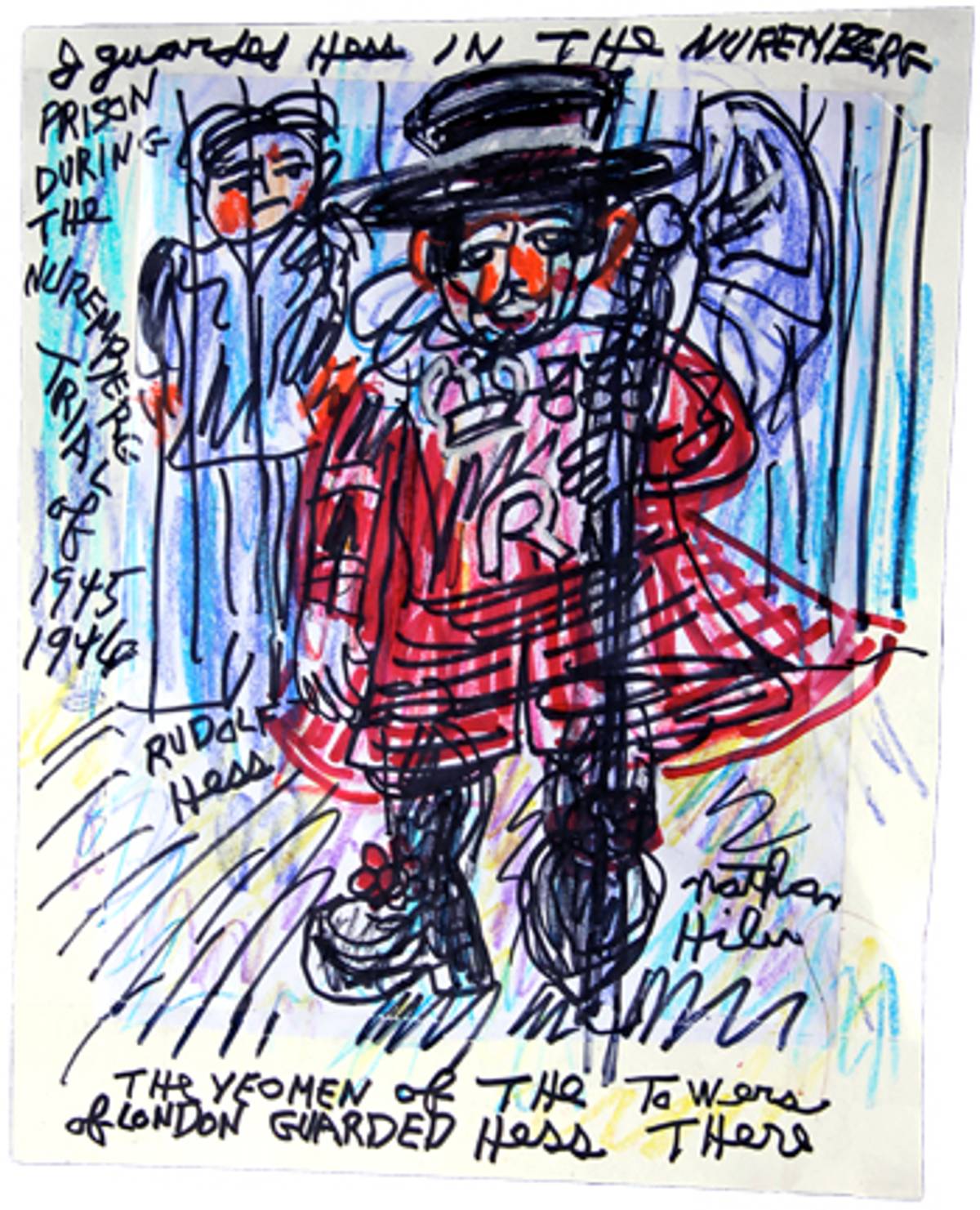

Nathan Hilu, an 87-year-old veteran who lives in subsidized housing adjoining the landmark Bialystoker Synagogue, may be the most significant Jewish Outsider artist you’ve never heard of. He is a denizen of New York’s Lower East Side and has vividly depicted the neighborhood’s shuls, markets, and rituals. Some of his other works, based on memories of guarding Nazi war criminals at Nuremberg, are on display in the Holocaust Resource Center at Queensborough Community College. He also enjoyed brief periods of recognition following a few exhibitions from the late 1970s through the mid-’90s at the now-defunct Cordy and Dalia Tawil galleries in New York and the Davenport Museum of Art in Iowa, since renamed the Figge—where two pieces, “The Kabbalist” and “King David With a Harp,” remain in the permanent collection.

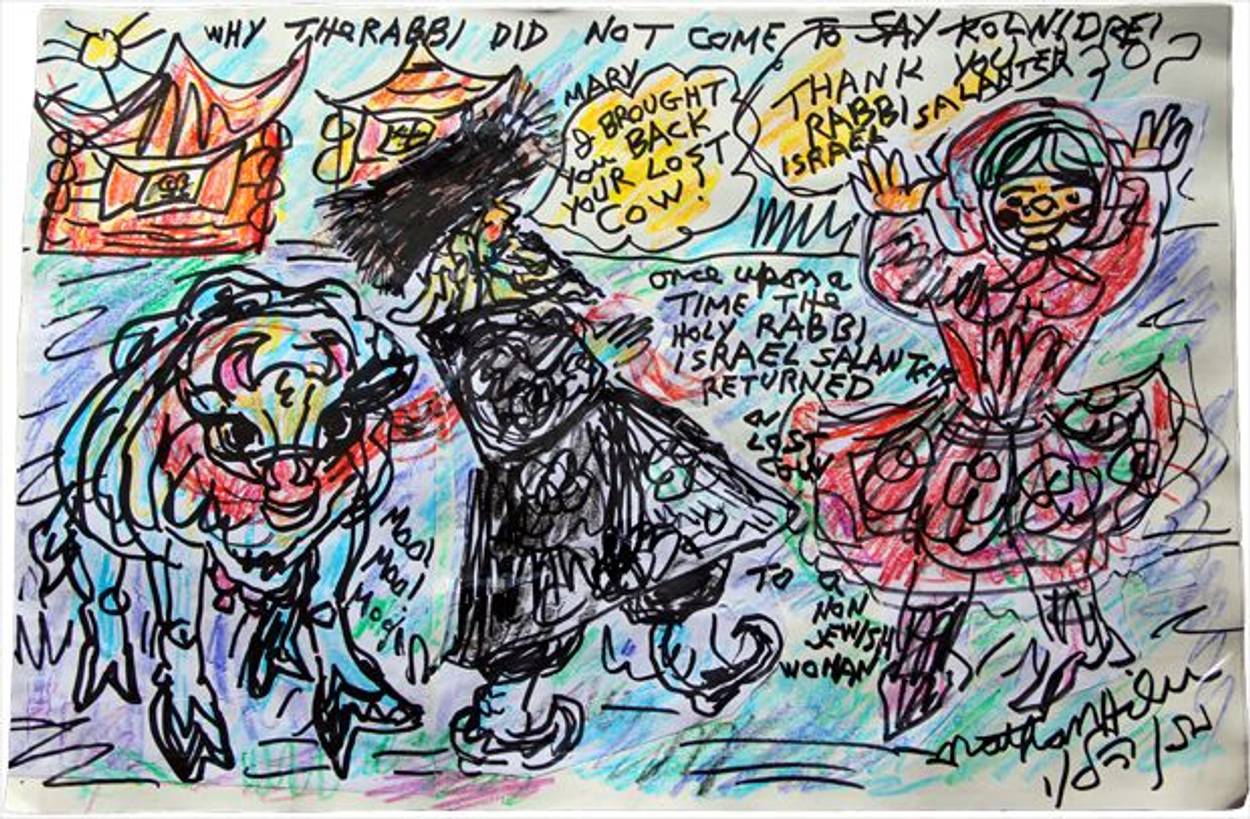

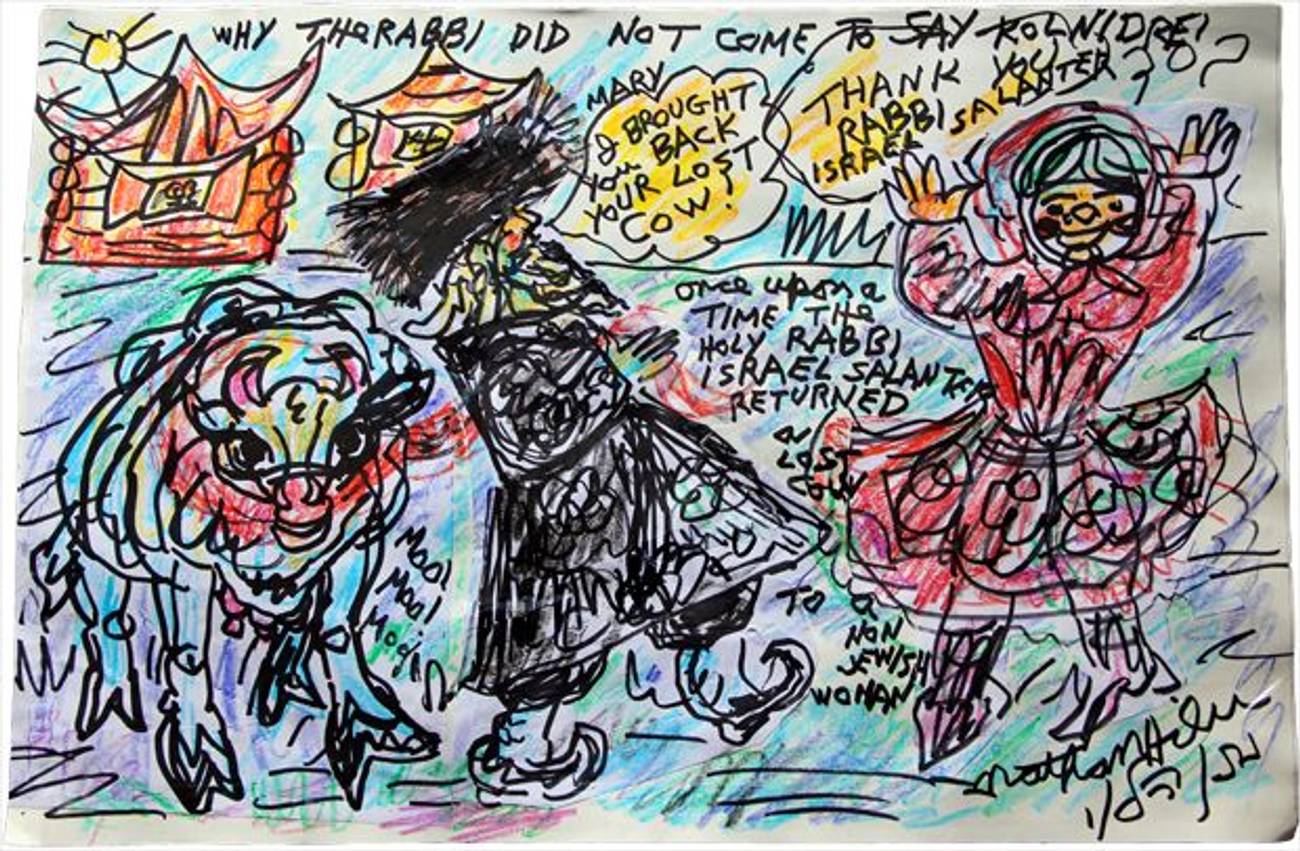

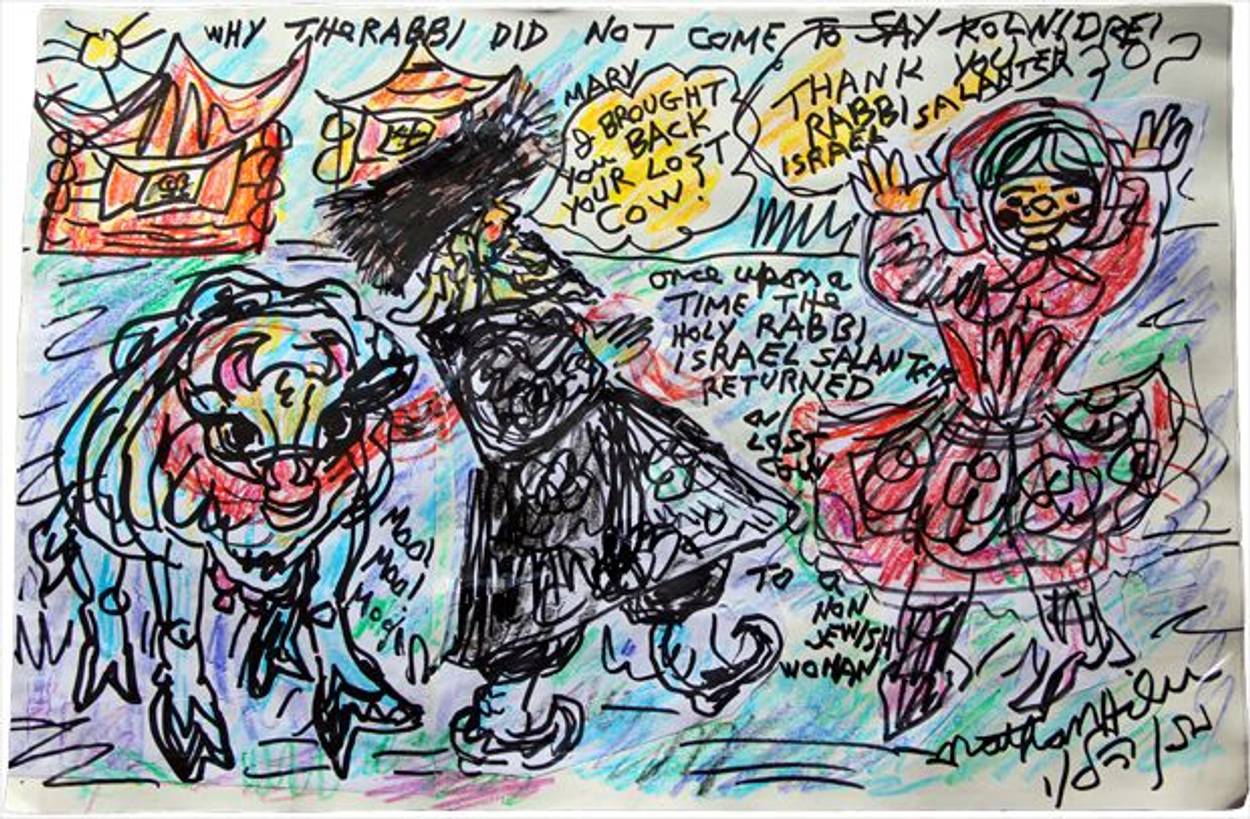

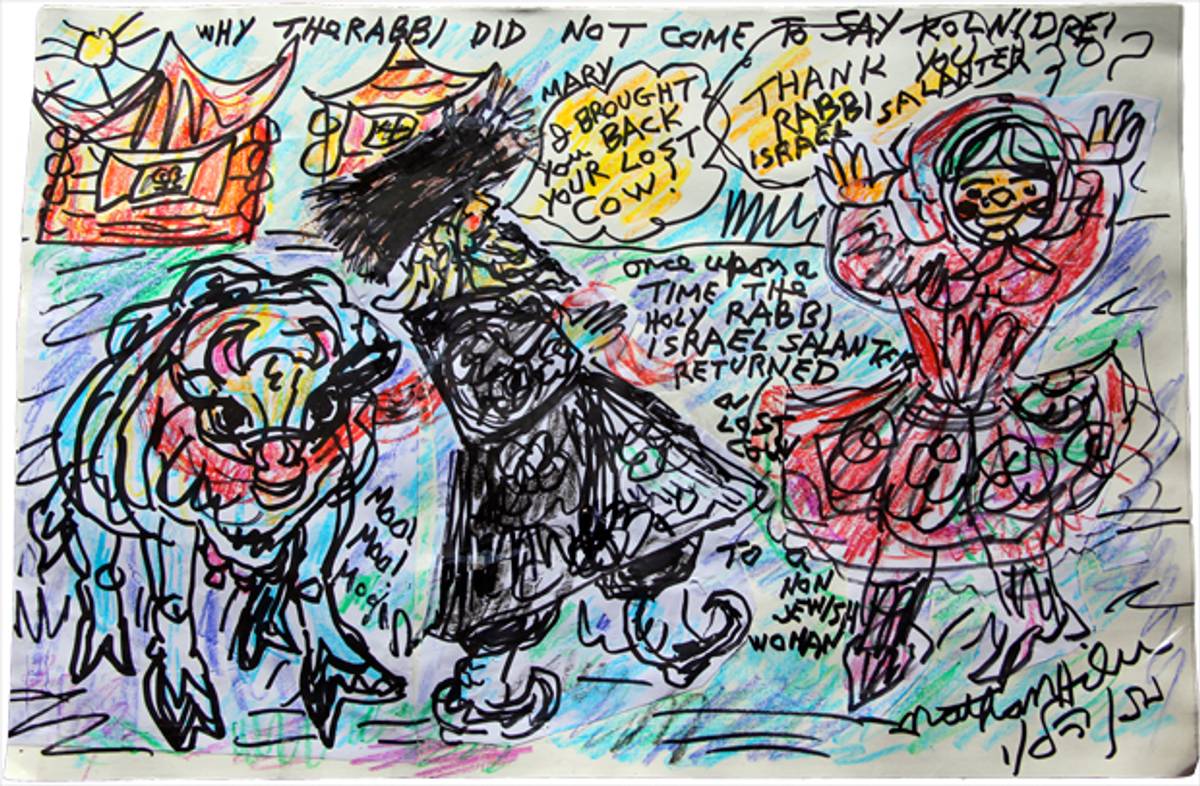

For the most part, however, Hilu has operated beneath the art-world radar, drawing at an almost frenzied pace with any available materials, usually Sharpie markers on office paper or oak tag. Yet his rough-hewn creations—embedded with text, disregarding normal rules of perspective, usually collaged, patched with clear tape, and covered on both sides—are powerful artworks that are also monuments to the Jewish experience. (Hilu doesn’t date or title his drawings, though some have assumed titles based on their subjects or accompanying text, making this body of work especially hard to catalog.)

Hilu is getting some renewed attention thanks to a show at Hebrew Union College’s museum in New York through the end of March. The exhibit offers a glimpse of Hilu’s universe, in which sacred teachings, history, memory, and fantasy intertwine. Curator Laura Kruger, who learned of Hilu through a smaller 2010 installation at the Educational Alliance, has selected 48 examples and archived more than 150 (Hilu brings in fresh shopping bags of material every week). To support Hilu, who subsists on his pension, HUC is selling the works (except for 12 on loan from Rabbi Herman Lowenhar of Congregation Derech Emunah) for prices ranging from $200 to $1,000. Without a dealer, he has mostly bartered or outright given his work away.

The survey covers all of Hilu’s major themes, which also include biblical and midrashic stories and Eastern European folklore. There are richly detailed renderings of Jacob’s granddaughter Serah playing her violin as she tells him that Joseph is still alive (referencing Louis Ginzberg’s Legends of the Bible) and of the “Chofitz Chaim” performing an exorcism of a dybbuk from a young girl (as told to him by the late Rabbi Yaakov Yitzchak Spiegel of the First Roumanian-American Congregation).

Among his more typical, quicker sketches are Jonah swallowed by the fish, somewhat whimsically kvetching “oiy veh” through a speech bubble, and God braiding Eve’s hair in preparation for her marriage to Adam. Annotated portraits of Hermann Goering and other high-level Nazis Hilu encountered at Nuremberg and depictions of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising reflect what Kruger calls the artist’s “almost biblical outrage” over the Holocaust. There is a rich sampling of scenes from a largely bygone Lower East Side, like a poultry shop with chickens lined up for the pre-Yom Kippur kapparot, and homages to historic shuls from Anshe Slonim (now the Angel Orensanz Foundation) to Beth Hamedrash Hagadol.

“It’s a visual journal of his life, back and forth, between the present, the nearby past and the biblical past,” explains Kruger, noting that words and images “are always together” in his work and erupt “like a stream of consciousness.” Indeed, Hilu often conflates ancient and modern legends, history, and his own experiences, a contemporary commentator interpreting the 20th century while also placing himself in it.

It is difficult to reconstruct the details of his past, but some broad strokes have emerged over the years from his stories and his work. Born on the Lower East Side to Syrian immigrants, he moved with his family to Pittsburgh, where he lived in the Irene Kaufman Settlement House, attended the Hebrew Institute, and was raised in the community’s dominant Ashkenazi traditions. At 18, Hilu enlisted and was stationed in France and Austria before serving with the security detachment for the Nuremberg prison and trial. According to Hilu, Gen. Patton himself encouraged him to become a career Army man, saying there were enough Jewish doctors and lawyers.

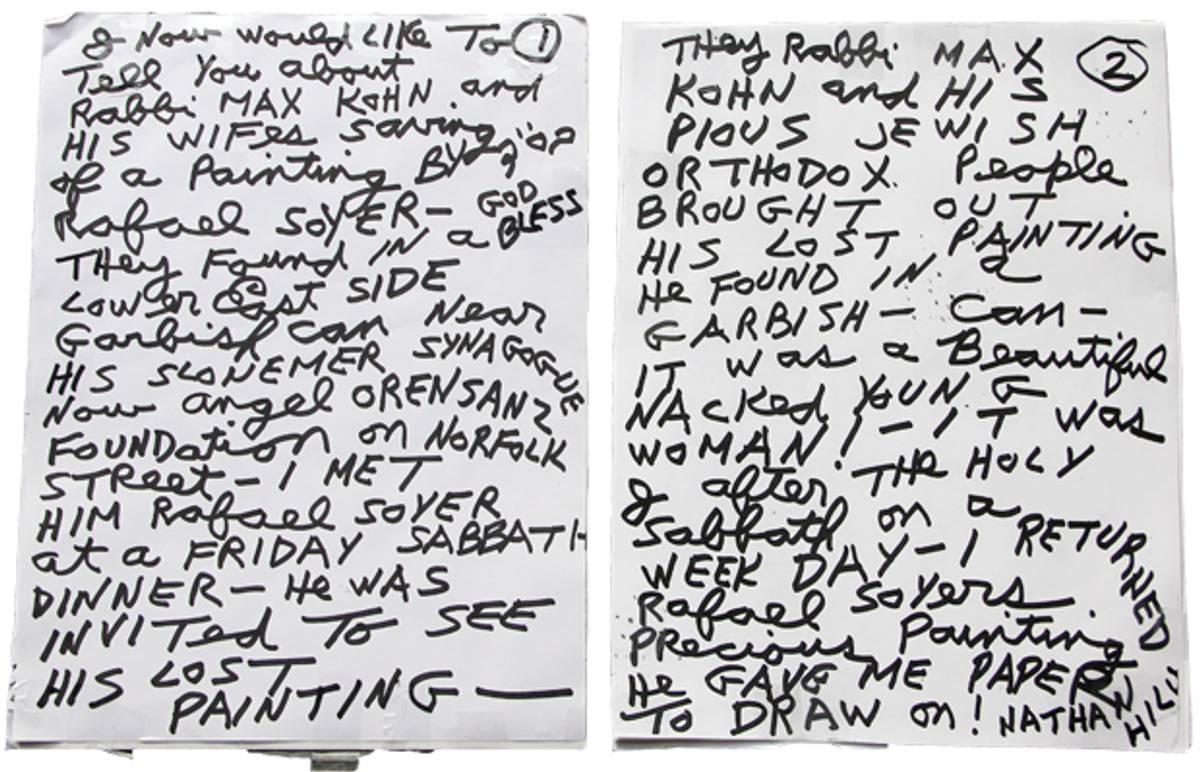

Hilu studied Japanese and Russian at an Army language school in California, was stationed in Japan during the Korean War, and served as a specialist in the Cold War. Following his retirement from the military, Hilu moved back to New York. He worked at a Midtown book and record store called Book Master and had his longest stretch of civilian employment at Bookazine, a New York distributor of books and magazines. The company’s owners, and publisher Harry Abrams, to whom they introduced Hilu, patronized his art and, it seems, supplied him with finer quality Sennelier oil pastels and handmade Fabriano paper that he used to make his most fully developed works.

For a meeting with editors in Tablet’s offices last month, Hilu feverishly spent the prior weekend putting together what he called his curriculum vitae. It was essentially a narrative biography in the form of a unique illustrated artist’s book encapsulating the formative memories, anecdotes, stories, and accomplishments Hilu has articulated so many times now that he recites them almost verbatim. The numbered, two-sided, unbound, out-of-order document—rife with typos, cross-outs, and redundancies, but also poetic, at times elegiac, pictures and verses—reads like a mad if utterly intriguing testimonial.

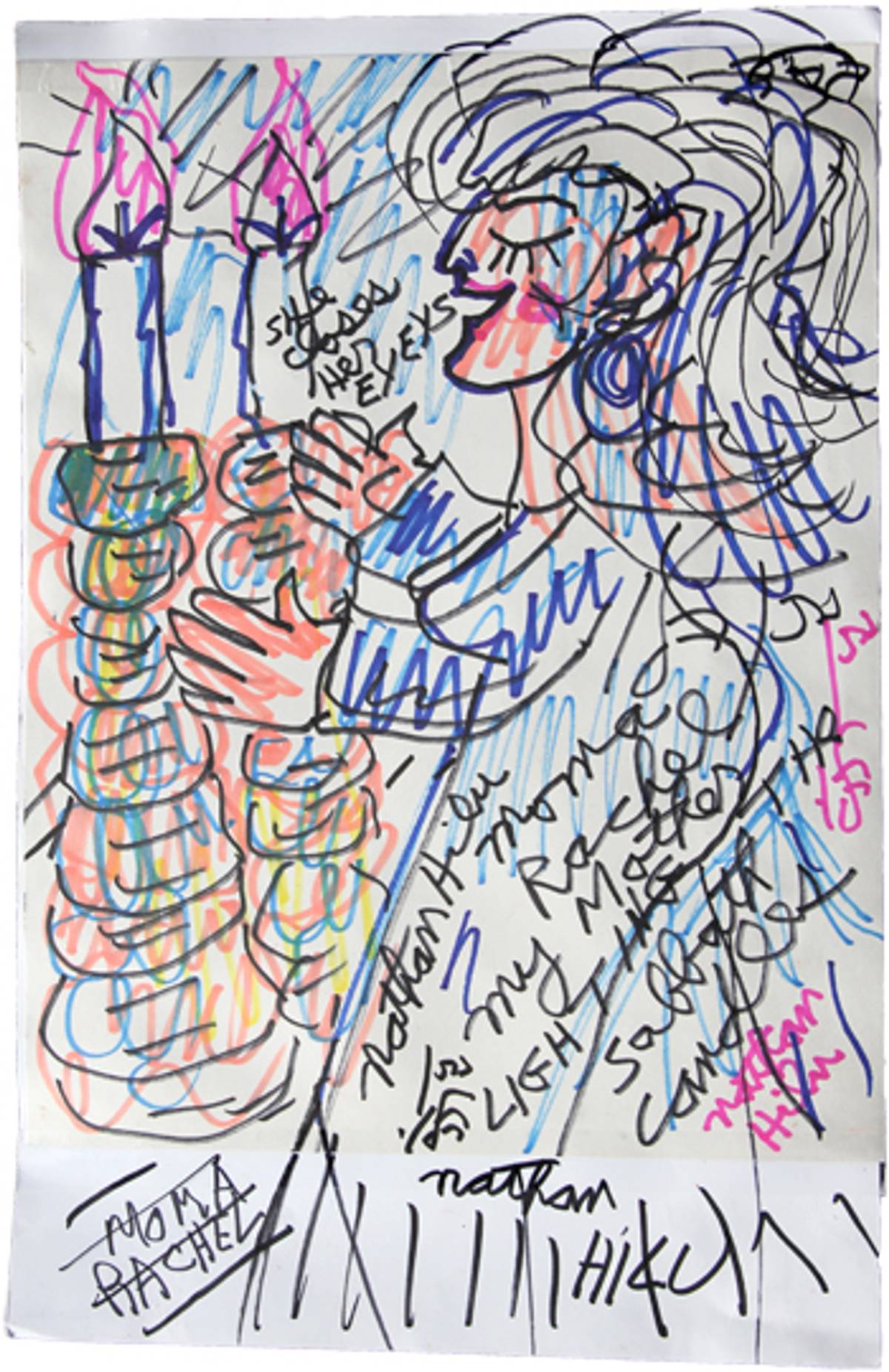

Hilu proudly identifies his grandfather, “Hacham Bashi” Nissim Andibo as the “Chief Rabbi of Damascus,” who supposedly blessed Israeli spy Eli Cohen before his hanging, and poignantly describes his mother, Rachel, as his “first art teacher,” explaining: “She would say draw the bird outside of my window on my pillow case; I would and she would sew a beautiful robin.” He details wartime adventures such as being roped into the Vatican to witness the canonization of Francesca Cabrini, the first American saint, and repeatedly provides his official RA#33969598. He cites every institution that has acquired his work and every publication that has featured it.

He is big on giving thanks. He acknowledges everyone from Emma Kaufman, for giving him a Tarzan coloring book when he was a poor boy, to Rosanne at the Village Copier and Rabbi Gary and “Rebbisa” Pollock of Congregation Lomdei Torah in Brooklyn “for their Jewish kindness in serving me tasty shabbis dinner.” Apparently also essential to understanding Hilu are reminiscences such as one about a vendor who used to sell sweet potatoes on Houston Street and ran over to Hilu as he was drawing him on a snowy day with a free hot potato to keep his hands warm.

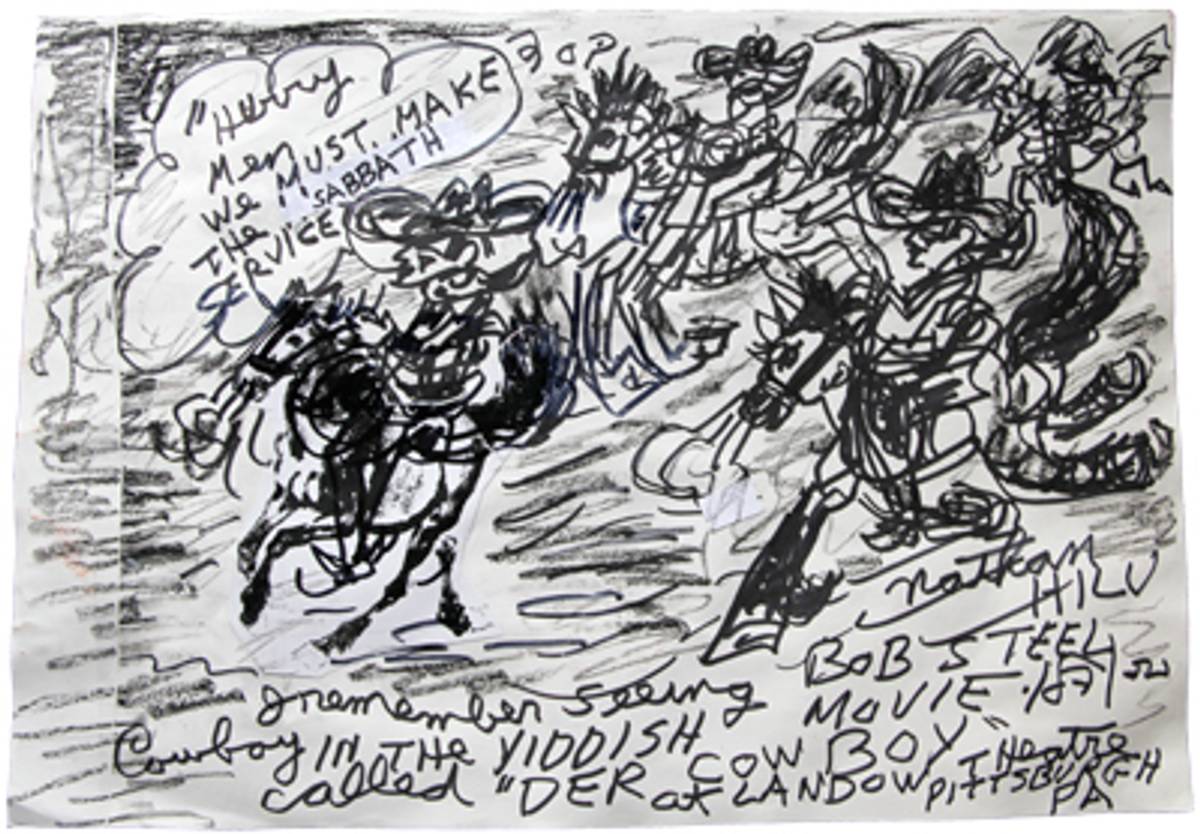

As ever, Hilu came to Tablet with a shopping bag full of work: I.B. Singer in front of the long-closed Garden Cafeteria; a Pittsburgh theater showing a film about a Yiddish cowboy; David slaying Goliath based on Thor from a book of fairy tales; and his version of the famous story about how early 19th-century Rabbi Israel Salanter, father of the ethical musar movement, went missing on Kol Nidre night, purportedly to return a lost cow to a Christian woman. Hilu’s most common refrains were “Shema Yisrael!” and “Hear me out,” reflecting his sense of awe and compulsion to communicate. At one point, with great urgency, he declared, “This is all gone. This is important. You should hold on to this. You should make copies. This is all Yiddishkeit.”

Though not obviously religious, Hilu sees piety in the everyman and spirituality in the everyday. He heeds both the advice of his early mentor Abel Warshawsky, the American Impressionist, that “an artist must have veltshmerz,” or an ability to feel the pain of the world, and the simple wisdom imparted to him by Rabbi Moshe Feinstein: “It’s a joy to be a Yid!” Referring to his associations with a long list of religious figures, Hilu said, “You won’t believe it: I worked with the biggest rabbis in the world and they wrote all the Hebrew for me. I never had anything done without a rabbi.”

While Hilu humbly refers to himself as a “poor Jewish schlepper,” he also compares himself to Proust and Pissarro and is hungry for broader recognition. HUC’s efforts may bring him this; the work made an impression on several dealers in town for the annual Outsider Art Fair in January, and there are plans—still being worked out—for the show to travel to several venues in the United States and abroad. There’s the very real possibility, however, that, like other eccentric artists before him, Hilu’s value won’t be realized in his lifetime.

A few critics have disputed that Hilu is a so-called outsider, noting the sophistication of his cultural references and training as a commercial artist. His purposeful drawings do evade the sentimentality and schmaltz that plague much Jewish religious art, but his raw methods and style place him squarely in the art brut tradition. This doesn’t in any way diminish his output; in fact it helps explain why it is so potent. There is an almost naïf quality to his appreciation for the kindness of others, pure faith, lack of commercial motivation, and impulse to draw, making his life and work all the more authentic.

We may not be able to confirm every detail of Hilu’s mesorah, just as we cannot prove whether Jonah was swallowed by the fish, if God actually braided Eve’s hair, or what delayed Rabbi Salanter on Kol Nidre night—but does it even matter? These tales and, like them, the American Jewish immigrant experience and Holocaust, have become indelible parts of our tradition. Hilu, through his modern folklore, plays no small role in keeping them alive, and like Kilroy, another recurring motif, he asserts he was here.

Jeannie Rosenfeld, a Tablet Magazine contributing editor, writes about fine and decorative art.