The Industrial Removal Office

Letters to and from the early-20th-century immigration service that sent thousands of Jews to America’s heartland

“After seven weeks without work in the sucking whirlpool of New York, and being a greenhorn, you can just imagine how I suffered—hunger, thirst, torn and insulted from all sides. I somehow managed to survive. But in truth, I was in agony. … I ran around half starved from 5 o’clock in the morning until evening looking for work that pays a meager wage. And did I find anything? Yes! A bench in Hester Park. … But now, after being sent here by the Removal Office … to a beautiful and clean city, I feel as if newly born. My head no longer pounds from the elevated. My feet no longer shake from the subway…” This letter in Yiddish was sent by Morris Goldstein in October 1907 to the Industrial Removal Office, the organization that sent him to Columbus, Ohio.

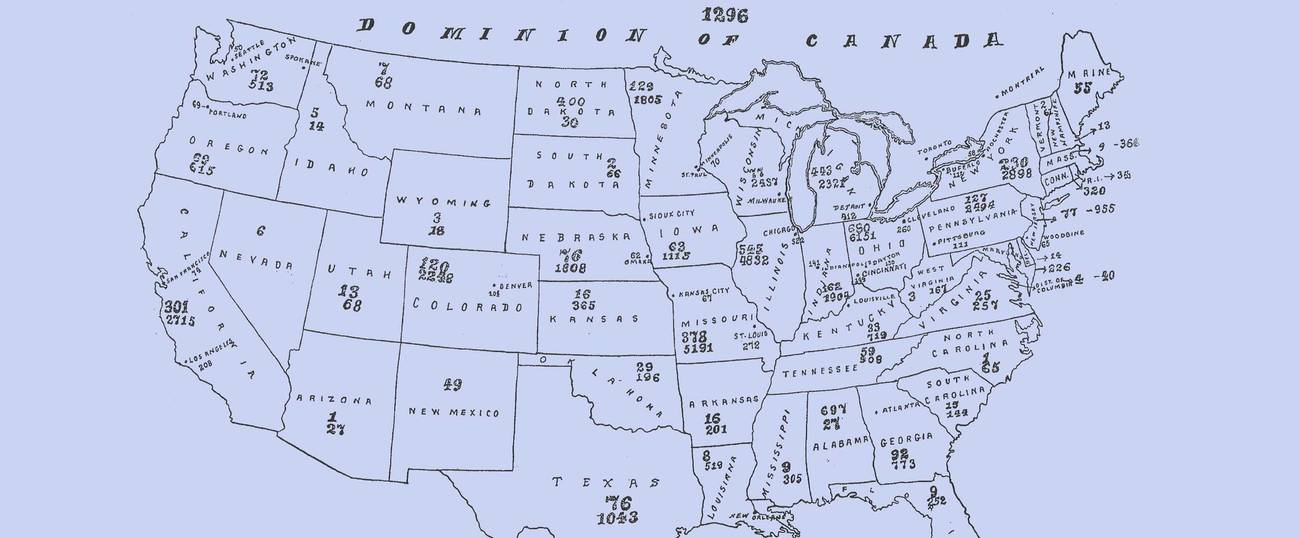

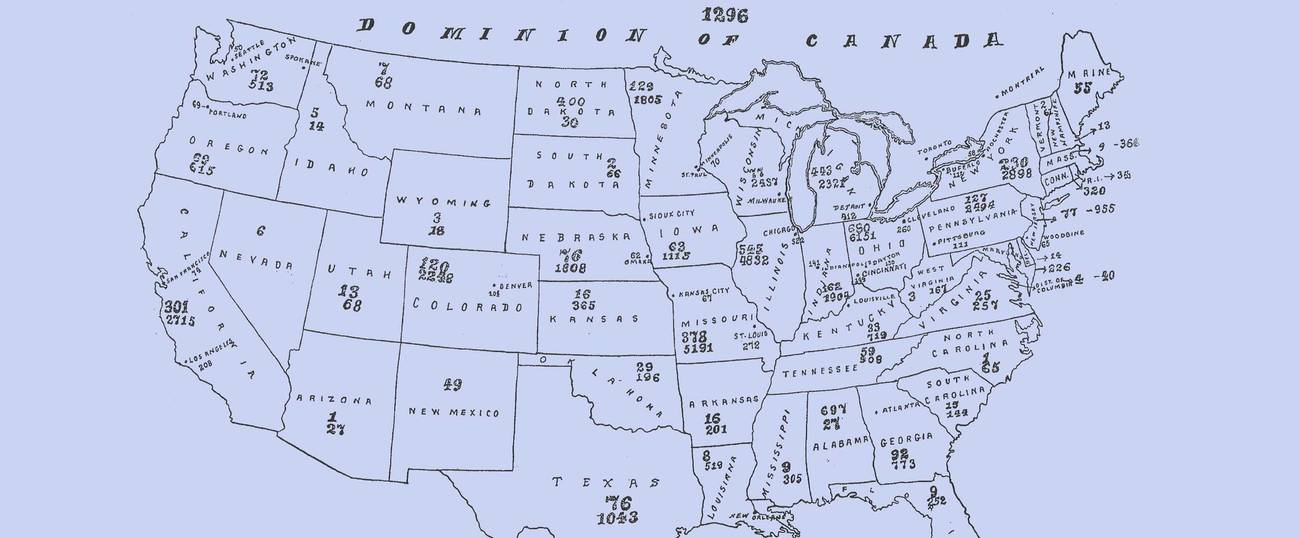

German American Jewish leaders created the Industrial Removal Office (IRO) in 1901 to remove unemployed eastern European Jewish immigrants from New York City and relocate them throughout the United States to smaller cities where Jewish communities and jobs existed. From its inception to its liquidation in 1922, the IRO dispatched 79,000 Jews to more than 1,000 American towns and cities. The IRO enlisted the cooperation of the local Jewish communities to secure employment and housing for the men they sent and to ease their settlement into the communities. The central office in New York City was staffed primarily by German-American Jews, who exhibited the same ambivalent attitudes toward the newcomers as did other German-Jewish philanthropies.

A number of factors motivated the German-Jewish leaders to create this organization. By 1900, New York held more than 500,000 Jews, the largest Jewish population of any city in the world. The unending flow of Jewish immigrants into New York’s Lower East Side generated enormous problems for the immigrants and the city’s Jewish establishment. Packed together in the Jewish quarter, the newcomers endured filth, poor sanitation, disease, and soaring rates of delinquency and crime. Dispersing the immigrants would alleviate some of these problems. It would also ease the immense burden placed upon New York’s Jewish charities by hundreds of indigent and sick newcomers.

Another factor also influenced the IRO’s founders. They and other native-born American-Jewish leaders believed that New York’s huge eastern European Jewish enclave offered a prime breeding ground for radical movements such as socialism and anarchism. Detaching the immigrants from this environment and shipping them to smaller Jewish communities in the Midwest, South, and West would forestall their subversion and facilitate their Americanization. IRO leaders, like others of their class, also worried that even the most admirable and assimilated American Jews would be judged as being no better than the worst of the immigrants. So they took measures that they believed would protect their own standing. They hoped that distributing the immigrants and thus aiding their Americanization would enhance the image of the Jew in the eyes of the general public and lessen anti-Semitism.

The IRO founders hired the German-born David Bressler (1874-1942) to manage the organization’s central office and direct its activities. Bressler came to the United States in 1884, and spent most of his adult life working with Jewish immigrants. He directed the work of the IRO till 1916. He then joined the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, in which he played an important role till his death.

All of the IRO’s activities were subsidized by the Jewish Colonization Association (ICA) and the Baron de Hirsch Fund. The ICA and the Fund had been established by the German-Jewish financier and philanthropist Baron Maurice de Hirsch (1831-1896). Hirsch believed that emigration provided the only permanent solution to the plight of the Jews in Russia. To this end he founded the ICA to settle Russian Jews on farming colonies in North and South America, and the Fund to provide aid to Jewish immigrants in the United States.

In order to secure the cooperation of Jewish charities and organizations in as many cities as possible, the IRO subsidized their operations by paying a local representative or agent a salary of $50 to $75 per month, and giving the Jewish community an allowance for every family or individual they placed. The IRO expected its local agents to find jobs and arrange for lodging, board, transportation, and other necessities of daily living for the immigrants. The local agent canvassed the city’s economy and job market and reported his findings and recommendations to the IRO. Upon receipt of the information, the IRO forwarded the resumes of men with pertinent occupations and awaited approval for them to be sent.

The IRO advertised its functions in the local Yiddish press and in settlement houses. Interested immigrants filled out applications at the main office, and the IRO placed qualified applicants on a list of prospective removals. Furnished with a small stipend and sometimes tools, each man was sent to an agent in a specific city who found him work in his trade or something reasonably close to it.

Although most immigrants remained in the cities where they were sent, some did not. The causes for their leaving varied. Loneliness, the fact that they had more relatives and friends in New York, and the lack of a Jewish environment or work seems to have been the chief motives for their departure. Sometimes the urge to try their luck somewhere else prompted men to leave. For whatever reason, a number of removals relocated several times before settling down.

Wherever they were, hundreds of the immigrants, or “removals” as they were called, wrote letters to the IRO. Most wrote to request that family, friends, or belongings be forwarded to them. Many wrote to complain about the treatment they received or about conditions in the place where they had been sent. Some, like Morris Goldstein, wrote to express their gratitude and praise for the IRO and their agents. Others wrote to describe their successes or failures and to articulate their hopes, dreams, and disappointments.

The letters give voice to ordinary people who were not prominent or movers and shakers. The letters speak about their worries and cares, their trials and tribulations, and how they adjusted or did not adjust to their surroundings. From their letters, we can gain some knowledge of the attitudes and ways in which eastern European Jewish immigrants looked at the world. Since the letters to the IRO were not written for publication, as letters to the Yiddish press often were, they also offer examples of the attitudes, tensions, and misunderstandings that poisoned relations between the immigrant eastern European Jews and the established German-Jewish community as represented by David Bressler and the IRO.

The vast majority of the immigrant correspondence was written in Yiddish. Most of it was translated into English by bilingual persons employed by the IRO. Some letters in English were written for the immigrants or by immigrants who knew English. What follows is a selection of the letters and the responses by David Bressler.

Letters of Gratitude

This immigrant’s experience with his friends and family contradicts the myth that Jews assist one another in times of crises and need. His personal experience, however, does not dissuade him from later contributing to the relief of Jews who are suffering in Russia. At the time, Wichita, Kansas, to which he was removed, contained approximately 150 Jews out of a general population of 45,000. Russian immigrants constituted 60 percent of the Jewish population. Wichita’s Jewish community supported one Orthodox and one Reform congregation, a Hebrew school, and a B’nai B’rith chapter. The Mr. Mann alluded to in this letter was B.I. Mann, a businessman, community leader, and the local IRO agent.

Wichita, Kansas

March 16, 1906

Dear Brothers of the Jewish Removal Office:

I beg you to forgive me for not thanking you when you sent me to this city a year ago, or when you sent my family to me six months ago. Now I come to thank you for me and my family from the bottom of my heart.

I see that you are the real doctors, bringing people back to life again. You need not look far, but take me as a living example. The day I came to your office asking you to help me leave New York, I felt like a dead person. I told myself that if you refused to send me, I would commit suicide. Those five weeks that I was out of work in New York seemed to me like 15 years, because I was without money.

My best friends from Europe, those who met me when I landed, humiliated me and made me feel as though I was being stuck with needles whenever I asked them for a piece of bread. In order to keep away from my so-called friends, I was forced to go to a free kitchen to get something to eat. Just imagine, my own brother-in-law reproached me and made me choke on every morsel he gave me.

Now, dear brothers, you sent me here to a person named Mr. Mann. He tried his best for me and found me a job. You can just imagine how thankful I am. I worked and made a living. Then, with your help, I brought my family here. And, thanks to God, I am making a respectable living.

I do not forget you for a single day, and my family and I always pray for you. I wish all of you, who work for such a good cause, health and a long life. I only wish other Jews can be helped the way you helped me a year ago. Now I have contributed some money to our society’s fund to help our suffering brethren in Russia.

From me, your best friend,

Chaim Zadik Lubin

My wife, who you sent to me, is named Chaye, and my 3-year-old son’s name is Zvi Hersh.

***

In addition to thanks, the following letter provides an interesting portrait of a small Jewish community in the deep South, in this case Meridian, Mississippi, seen from the perspective of an eastern European Jewish immigrant. The writer comments on the relations between Christians and Jews and hints at the rivalry between the older, more established German-Jewish community and the newcomers from eastern Europe. He also notes crimes committed by the immigrants, something the native Jewish community was always loath to publicize. Although undated, this letter was likely written in 1906 or 1907.

[Undated]

Dear Sir:

With a feeling of thankfulness I am writing to you this letter. You will recognize me as one of the clients of the Removal Office by the name of Leo Stamm.

It is five months since I have arrived to Meridian, and with pleasure will describe to you the condition in which the Jewish immigrants are around this neighborhood. The city of Meridian, where I am living, consists of about 75 Jewish families. They have been here for 8-10 years, and are all well-to-do. The most part of them are very rich, doing business in the millions. Three quarters of them are German Jews and the rest of them are Russian Jews, but every one of the Russian Jews is trying to get the title of a German Jew. Most of the business in the town is in the hands of the Jews and they are growing very rapidly in both power and riches.

The Christian population is very friendly to the Jews and the anti-Semitism is very low. This is because the Jews in this town are very honest and do business on business principles. Yet, there are some exceptions to this situation with the Russian Jews. That is because there were some crimes committed by Russian Jews against a few natives of this city. One misfortune was that a Jewish peddler stole a gold watch and chain from a farmer. Another case involved a clerk who ran away with hundreds of dollars from his employer. And what is done in New York every day is unexpected in a small town like this. And the natives of this city very often remember that these crimes were committed by Russian Jews.

For an honest working man, the South is a very good place to live. And here I send my advice to the enslaved Jews of New York, to leave that town as fast as they can, and come here to get the benefit of the good climate and the chance to make a good living.

To you I send my gratitude for all your kindness to the people who are applying to the Removal Office for help. I will never forget that immigrants with hardships are meeting such people like you….The Davidson family, who you sent here a few months ago, send their warmest regards. They settled themselves very well, just as I expected. They remember you as the one who helped them to leave New York. They are especially thankful that you sent them by way of Washington, as it saved them many hours of travel.

I hope you are all as well as you wish.

Yours very respectfully,

Leo Stamm

***

Although expressing thanks to the IRO for its help, this letter writer evinces resentment at the attitude displayed toward her by David Bressler when she applied for assistance. This letter highlights the misunderstandings and tension that sometimes occurred between the immigrants and those charged with assisting them. What the German-Jewish philanthropies perceived as efficient, modern, and “scientific” procedures, the eastern European Jew often saw as insensitive, impersonal, and heartless. The questions asked by Bressler to ascertain the financial status of the applicant were viewed by him as a necessary formality before granting the loan. Mrs. Friedman , however, saw the questioning as a humiliating and demeaning experience. At the time the letter was written, the Jewish population of Minneapolis numbered about 15,000. The community supported eight Orthodox and one Reform congregation, and a variety of Jewish social and charitable organizations. The Miss Foxe in the letter was the IRO agent in Minneapolis.

Sept. 15, 1912

823 15th Ave. S.

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Mr. Bressler,

Industrial Removal Office

Dear Sir:

Inclosed [sic] please find ten dollars ($10), the balance of the debt, which we contracted for my transportation to this city.

Allow me to thank you for your kind favor, which can really be called “good deeds”. You are reputed to be an educated and clever man, therefore you will not resent criticism that is extended to you. I mean to give mine in good intention.

There are different ways of doing things. The most important is courtesy. If the party that is looking for a favor should be refused gently, he will feel better then [sic] if he were granted the request and treated as if he was not among those that can be classed as human, and spoken to as if that party did not know the meaning of insult.

When I applied to you for transportation, I told you everything and the truth only. Yet it was not enough. You humiliated me by asking why I do not pawn my jewelry, which was pawned for the last five years, why I did not sell my furniture, which we did sell to pay my husbands [sic] way to Minneapolis. Then you went on asking me, why I do not borrow from friends, and when I told you I owe everybody, you suggested that I should leave my child some place with strangers and go to a hospital to have my second baby. At last, when I told you I intend to pay it all back as it is only a loan, you made me sign a note for $20. My husband had it all arranged with Miss Foxe to pay her $15 as soon as we are in position to do so.

Sir, I do not complain! In fact I am grateful to you. But the reason I mention it all is because you should not think everyone that comes into the office to ask for aid must be a cheat, a liar and ignorant. The few hours that I sat waiting, I had a chance to study the characters that came in. Some may be such I admit, but there are exceptions and a man like you ought to know the difference.

You will excuse us for not settling the bill as promised, because we paid the bills in turns. We are now clear from all debts. Nevertheless we are not less grateful to all our friends and good people for their kindness.

Mr. Friedman would like to have the note if possible.

Respectfully yours

Mrs. Samuel Friedman

***

Sept. 19, 1912

Mrs. Samuel Friedman

823 15th Ave. S.

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Dear Madam:

We are in receipt of your kind favor of the 15th instant with check for $10 as a balance in full of the loan made to you some time ago by this office. Thanks for your suggestions contained in your letter. We beg herewith to return your note signed by you Nov. 10, 1911, duly receipted.

Yours very truly,

INDUSTRIAL REMOVAL OFFICE

Letters of Complaint

No matter where the immigrants were sent, large numbers of them found their expectations unfulfilled. Many of them wrote the IRO to voice their complaints and vent their anger. Some felt they had been misled or lied to by the IRO. Others resented the attitude of the IRO and its agents. And some found adjusting to their new homes and jobs, or lack of jobs, difficult, and blamed the IRO for their troubles. A surprising number of these letters contain threats by the writer to expose the IRO or to commit suicide. A few of the suicide warnings were serious; most, however, were used to gain sympathy and force the IRO to act.

This removal accuses the IRO and its South Bend, Indiana, agent of “murdering” him. The letter contained no return address.

Benny Gerskoff

Aug. 23, 1905

Murderers! What did you want from us? Why did you send us to South Bend? We are going around hungry, and no work is found for us. We will die from hunger. The agent doesn’t care at all. Now there is no other way for us, but to go straight to the river.

Benny Gerskoff

South Bend, Indiana

***

The following letter from Seattle, Washington, complains about the lackadaisical attitude of the local agent. Seattle had a Jewish population of approximately 4,000. The Jewish community supported four Orthodox and one Reform congregation, a number of Jewish fraternal and social organizations and a settlement house for Jewish immigrants. A large number of Turkish Jews settled in Seattle before World War I. Leo Kohn was an elderly Jewish businessman who served as the IRO agent in Seattle.

Seattle, 16 Oct. 1909

Gentlemen of the Removal Office:

Alter Battler is writing to you, praying to pay attention to his words.

By sending me to Seattle, you have really killed me, as I am out of work over four weeks, destitute, lonely, naked, and in a position of starvation.

You ought to know that Seattle is a place for rich people only, but not for working men, who never can get work there for lack of factories.

Mr. Kohn provided me with work in a certain factory, but after I stayed two weeks I was discharged, having been accused of organizing a strike. Further, he does nothing for me. He is always occupied with young ladies, and when he sends me sometimes to employers, he takes their addresses from advertisements.

Nothing remains for me but to commit suicide. I appeal to you to help me go back East. Otherwise I will be compelled to write to the immigrant society.

I do not know why you inquired about my character and integrity. You are familiar with Seattle and know there is nothing here to steal but air and wind. Please answer soon.

Alter Battler

Seattle, Washington

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Robert Rockaway is professor emeritus at Tel Aviv University, and the author of But He Was Good to His Mother: The Lives and Crimes of Jewish Gangsters

Robert Rockaway is professor emeritus at Tel Aviv University, and the author of But He Was Good to His Mother: The Lives and Crimes of Jewish Gangsters.