Is the U.S. Constitution Pro-Slavery?

Sean Wilentz says it’s complicated

I.

Several months ago a slender volume on slavery and the United States Constitution by my friend Sean Wilentz waded ashore in Massachusetts, courtesy of Harvard University Press, found a friendly reception at Harvard itself, fought its way inland, captured a lower hill at The New York Times Book Review, penetrated the swamplands of The Nation, came under withering attack from tanks and airships at The New York Review of Books, returned fire, came under further attack in the letters column, attracted allies, escaped into the hinterlands, and by now has a good prospect (if I judge the reviews correctly, and especially the outcome of the pitched battle at The New York Review, this past June) of planting its flag above the United States as a whole. It may take 20 years, but the result will be salutary.

Wilentz’s book is No Property in Man: Slavery and Antislavery at the Nation’s Founding, and (if I allow my predictions likewise to march hither and yon) the argument it proposes will reshape American thinking on a deep American matter, which hinges on an absurdly simple question, to wit: When the United States was founded, was it fundamentally a center of oppression, pretending to be a progressive advance in human affairs? Or was the United States authentically a progressive advance, disfigured by some inherited traits?

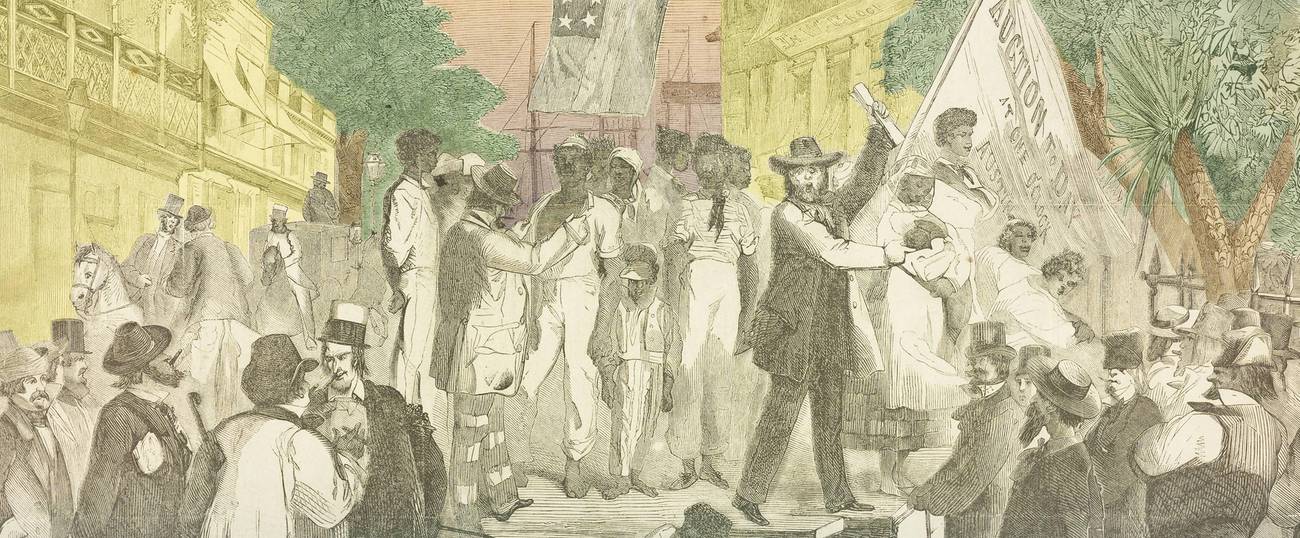

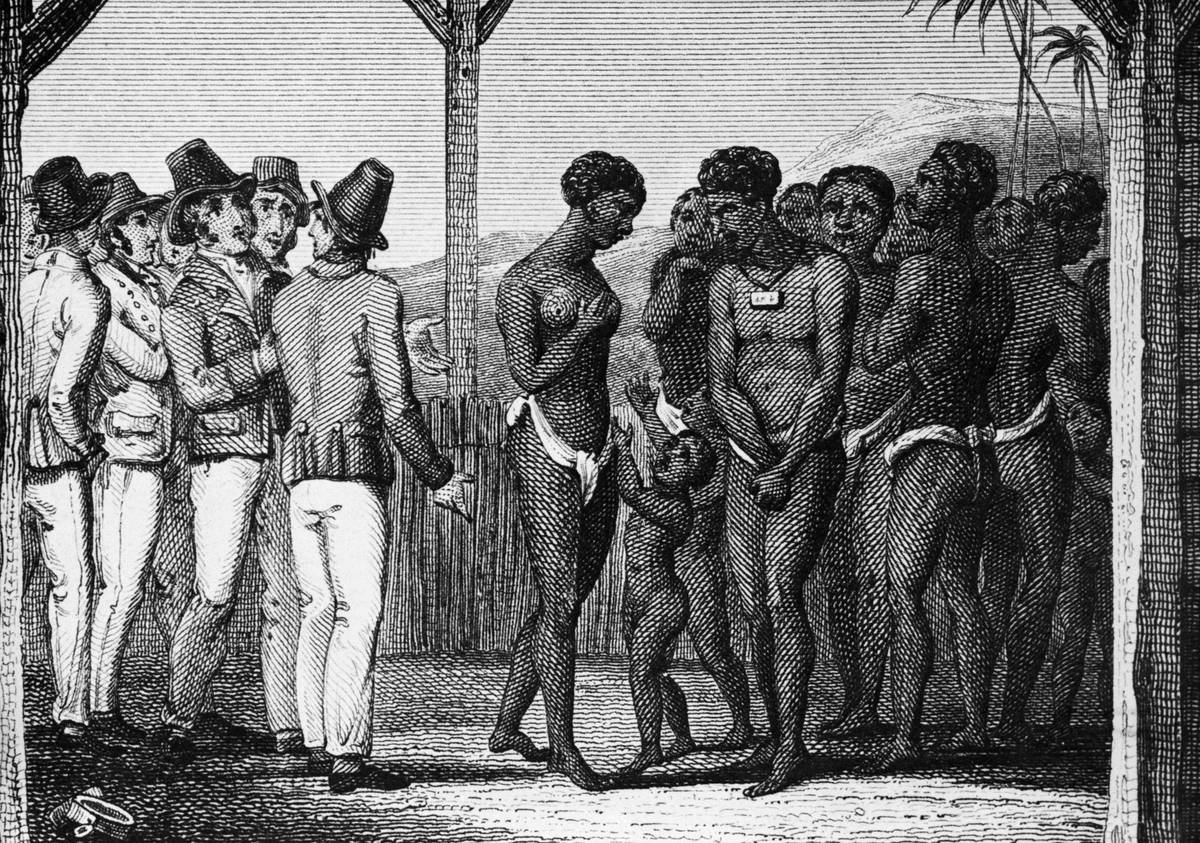

The immediate topic is the several clauses of the Constitution that bear on slavery, and how to interpret them. Those are the barbarous clauses—the clause that distinguishes between “persons” who are “free,” and “persons” who are not, with the latter to be tabulated as three-fifths of the former; the clause mandating that any “person” who is “held to service or labor” in one state and escapes to another state shall be returned; and, among other stipulations, the clause forbidding Congress for 20 years from interfering, except in a small way by taxation, with the “Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit”—which was a delicate reference to the African slave trade.

The clauses were approved at the Constitutional Convention at Philadelphia in 1787, principally on the demand of pro-slavery zealots from the Lower South. And the dispute over how to interpret them began at once, with the pro-slavery zealots taking an expansive view. The clauses, in their interpretation, signified a larger constitutional endorsement of slavery, which rested on respect for slavery’s underlying principle, which was a right to an extreme version of private property, with property deemed to extend to the ownership of human beings.

Wilentz tells us that, after the convention, the pro-slavery zealots launched something of a campaign to sell the world on their interpretation. And the campaign had successes. The leaders of the white South as a whole came to insist on those particular understandings, and Federal judges ended up accepting the interpretation. Eventually the Supreme Court itself agreed and, in the Dred Scott decision in 1857, imposed a broadly pro-slavery interpretation of the Constitution on America as a whole, and not just on the slave states, as if branding a giant S on America’s forehead.

Nor was it only slavery’s proponents who accepted these views. The intransigents of the abolitionist cause were known as the “immediatists,” and they, too, ended up subscribing to the same interpretation, except in an upside-down version, which led them to reason that, if the Constitution legitimated slavery, slavery must surely delegitimate the Constitution. The immediatists responded by disavowing the Constitution in toto, and disavowing the government that came out of the Constitution, and disavowing the government’s procedures, too, such as voting.

And a few hints or seedlings from those ideas, wafting their way out of the 18th and 19th centuries, have found fertile ground here and there amidst the glooms of our own moment. Several generations of historians, by conducting serious studies of American slavery, have succeeded in darkening the national mood, and a great many people, contemplating what the historians have revealed, have ended up concluding that, all in all, the immediatists may have been right: The Constitution was a shameful thing. And, by extension, the temptation has sometimes been strong to look upon the American Revolution as a whole and the early American republic as an immense crime, such that, whenever we glance far enough into the past, we are bound to recoil in moral embarrassment.

Intellectual fashion in modern-day America has, in these ways, fallen into the same mood of penitence and humility that has overwhelmed a portion of the European imagination in the present era. Except that, where the Europeans have reproached themselves for the history of European imperialism, and have lost confidence in their own culture and have halfway given up on the idea of achieving anything large and magnificent in the future, we Americans have pinned our own dismay on the history of American slavery, with a side glance toward the history of the Indian wars. And we, too, have lost confidence in our own culture and have lost the belief that we have the moral right to try to achieve anything grand or impressive in our own future. The political crises of Western Europe owe something to those guilt-stricken reflections in their European version, not just to economic and demographic trends and the rise of right-wing movements. And the political crisis in America has followed a parallel course—a crisis that owes something to a left-wing despair over the national history and a revulsion at the American claim to democratic glory, and not just to larger developments on the political right.

But those are my own reflections. I do not mean to attribute them to Wilentz’s book. He is a politically engaged writer, happy to participate in present-day disputations and to bang the table on behalf of his chosen heroes from among the Democratic politicians. But his political essays have never occupied more than a small corner of his work, and, in any case, he has always been scrupulous about keeping his present-day preoccupations from bleeding into his other interests. You can see this in his commentaries on American popular music and the American bohemia (for instance, in a touching and autobiographical introduction he contributed last year to a volume of historic Greenwich Village photographs, New York Scenes, by Fred W. McDarrah, the Village Voice photographer)—which are cultural essays pure and simple, and not contributions to a political cause.

II.

The writings that stand at the center of Wilentz’s work are his scholarly studies of American history. Those studies draw on what seems to me to be the authentic gift of a natural historian, something rare, which is the ability to experience the long-ago past as if it were a personal memory, or a family wisdom passed down through rumor and the grandparents, and not as a construction worked up from the quarrels and aspirations of the present.

His book on slavery and the Constitution goes to the heart of the present-day consternation over the national identity and its history. But his method of inquiry is to acknowledge the modern debate, and to linger over it for a moment or two, and then to leave it behind, as if with a sigh of relief, in favor of the past, where he appears to feel at home. The past in this instance means an 18th-century era, difficult in our own day to remember, when slavery was an all-but universally accepted social practice.

The practice was solidly established not just in the colonies that went on to become the Southern half of the United States, but in all of the British colonies, and, for that matter, in almost every part of the world. Slavery was thought to be common sense; was known to be traditional; was acknowledged in the classical literature that stood at the core of higher education; was thought (except by a handful of Christian dissenters) to be divinely endorsed, as recognized not just by one religion, but by all the religions; was a key to the economy; was regarded as an imperial interest by all of the competing empires around the world.

But Wilentz also reminds us that, in the middle years of 18th century, the doctrines of Enlightenment philosophy were beginning to gain adherents in one corner or another of European life, and were spreading to other corners, sometimes with amazing speed. One of those corners was across the seas, where, in the American colonies, the philosophical doctrines struck roots more deeply than anywhere else.

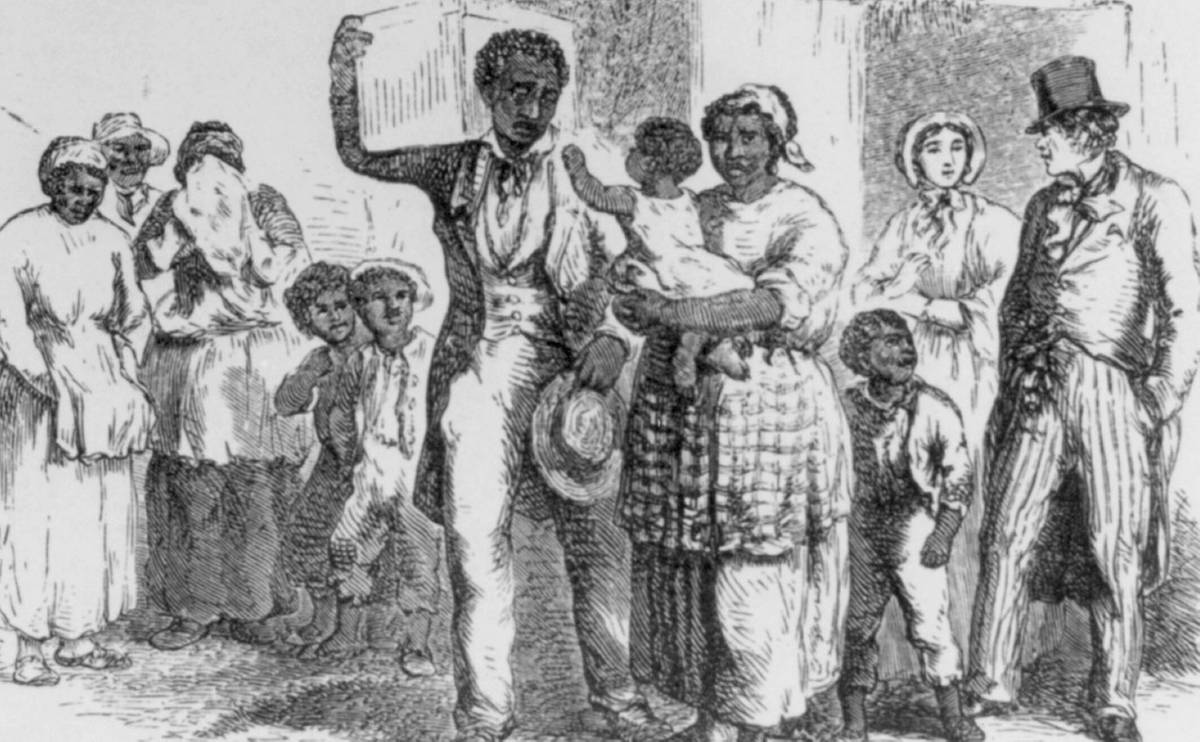

In America, a radical protrusion from those same doctrines began to generate, here and there, a vigorous questioning of ancient and universal principle in regard to slavery. This was something new—a questioning not just on grounds of a certain unusual sort of Christian piety, or as an idiosyncratic interpretation of law, which already could be seen in Great Britain, but with an eye to practical action. “Organized antislavery politics,” Wilentz tells us, “originated in America,” which is not a small thing to consider.

The organized politics figured as a tiny strand within the larger Revolution of 1776, which right away swelled into a larger strand. In 1777, the republic of Vermont—not yet a state—adopted what he describes as “the first written constitution in history to ban adult slavery.” Benjamin Franklin’s Philadelphia Abolition Society became, in 1783, the world’s first anti-slavery organization. Wilentz tells us that, in New York City in that era, 20% of the households included at least one slave, which was a higher percentage than in the Southern states. Even so, a group of New Yorkers, Alexander Hamilton among them, got up their own anti-slavery committee.

By the time of the Constitutional Convention, a handful of states in the North had either done away with slavery or were on their way to doing so. A few abolitionist breezes began to stir even in the Upper South, though without leading to practical action.

III.

The Constitutional Convention was bound to bring about a major showdown, then, on this one issue. Only, instead of pitting the new Enlightenment doctrines against the unreformed customs of an earlier age, the showdown pitted one American understanding of Enlightenment doctrine against a second American understanding—pitted the delegates who considered that, logically speaking, the principles of the American Revolution ought to rid the new United States of slavery, against the delegates who rallied around their extreme concept of private property. Here was the Enlightenment in its two versions, the humane and the inhumane. Anyone who has read Wilentz’s earlier historical studies will recognize that he commands an additional talent or perhaps a gusto for distinguishing among the components of complicated debates, as if slicing a pear, and in No Property in Man he looks into the minutes of the debate at Philadelphia and the private notes of James Madison and other documents, together with the Constitution itself, and, with a flick of the knife, separates the parts.

He dismisses out of hand the interpretation that reduces the convention and the Constitution that it produced to a shady deal between the slave owners of the South and the sellout delegates of the North. There were, instead, four parties to the debate, all of whom he takes seriously, or perhaps more than four, given that certain of the participants, being politicians, expressed themselves disingenuously at one moment or another, and, in that fashion, lathered a foam of inauthentic arguments over a solid base of authentic arguments. The pro-slavery firebrands from the Lower South comprised the first of those parties, and they presented their case with a ferocity that led them repeatedly to threaten to bolt the convention and remove their states from the proposed new union—quite as if those people had already intuited that a slave society such as their own was not going to find a stable home within a project like the United States.

The delegates from Virginia and the Upper South were likewise pro-slavery, but in a different manner, vexed and contradictory, which led them to be anti-slavery on philosophical grounds, even while determined on pragmatic grounds, or perhaps on grounds of panicky desperation, to preserve slavery for the foreseeable future. Madison was one of those contortionist Virginians. It is strange and a little appalling to consider what the man was like—the supreme intellect of American political theory who, together with his fellow Virginians, lived in terror of the enslaved population and of what might happen if the shackles were removed.

What may have been the single most dramatic anti-slavery speech at the Philadelphia convention was delivered by the very wealthy George Mason of Virginia, who owned 300 slaves and ended up freeing none of them. The mixture of anti-slavery eloquence, terrorized support for slavery, and lofty intellect appears to have been a kind of acid, which dissolved the delegates from the Upper South into a puddle of confusion at Philadelphia—now voting for measures that were plainly and nobly designed to bring slavery to an end someday, now for measures that were designed to shore it up in the meanwhile.

The ambivalent slavery-supporters of the Upper South had their Northern counterparts, who were philosophically opposed to slavery and nonetheless voted with the South on questions of slavery, and did so for reasons that appear to have been honestly arrived at, in conformity with their own business interests, and in conformity with their political interest in securing a national union, but also in conformity, or so they imagined, with philosophical principle, in the sincerely held belief that slavery was on its way to extinction, anyhow. And the fourth party in the debate were the frankly and consistently anti-slavery delegates, who seem to have harbored confusions of their own, such that Benjamin Franklin, a world leader of the abolitionist cause, who ought to have delivered an even sharper and more persuasive denunciation of slavery than the slave-owning Mason of Virginia, chose instead, for reasons that Wilentz uncharacteristically fails to explain, to bite his tongue (though he spoke up afterward).

The outcome of these convoluted deliberations, in Wilentz’s summary, was not, in fact, an endorsement of a right to private property in human beings. Nor was the outcome the creation of a slave republic, not on the national scale, anyway. The outcome was a puzzlement. The pro-slavery delegates secured their several clauses, but they were unable to secure the point that chiefly mattered to them, which was an explicit recognition or endorsement in the Constitution of the legitimacy of slavery. They said they secured it, and their claim to having done so has had an immense and unfortunate influence on American history.

But the anti-slavery delegates and some of the ambivalent-on-slavery delegates were adamant in giving them no such recognition or endorsement—adamant in refusing to acknowledge a right to “property in man.” Madison, the aspirationally anti-slavery slave-owner, was one of those adamant people. The odd-sounding circumlocutions in the crucial clauses—the references to “persons” instead of slaves, as in “persons” who happened not to be free, or “persons bound in labor”—were adopted precisely in order to avoid inscribing the fateful words slave or slavery into the Constitution.

Some of the delegates may have preferred elliptical language on cosmetic grounds, in the hope of sparing themselves the disgrace of having voted for a visibly ghastly document. But the principal motivation was philosophical. A majority of the delegates genuinely wanted to avoid writing barbarism into civilization.

The Constitution acknowledged and abided the existence of slavery in some of the states, which was a social reality and could not be avoided. But the federal union was not yet a reality. The purpose of the Constitution was to bring a new reality into being. And the delegates, in their majority, were determined to prevent the founding charter from offering any hint of legal approval for slavery.

There were practical implications, too, which everyone understood. Everyone knew that the American republic, as of 1787, was destined to grow, both in the population of the already-existing states and in the number of states, once some of the federal territories in the West had acquired a sufficiently large population to advance into statehood. By preventing the Constitution from recognizing the legitimacy of slave-ownership, the delegates insured that nothing from a federal standpoint was going to impose slavery on the federal territories. This made it easier to imagine that free territories would remain free, and made it easier to imagine that, in the future, when the free territories ripened into states, their statehood would likewise be free. No one could know in 1787 whether the free states would eventually end up more numerous and populous than the slave states, or less so.

But by keeping an explicit endorsement of slavery out of the Constitution, the delegates left open the possibility that, sooner or later, the free states would, in fact, become more numerous and more populous, with a larger representation in the federal Congress and the Senate, and more electors in the Electoral College. And everyone understood that, if and when the free states got the upper hand, a Constitution that conferred all sorts of powers on the federal government but failed to confer a legitimacy on slavery would leave the free states free to take action.

Would the free states choose to do so? Another unknowable. But the delegates did know they had left open the possibility—even if the delegates from the Lower South, who had their worries, were intent on persuading the world otherwise.

The Constitution, in sum, was a “paradox,” in Wilentz’s phrase. It was the expression of a conflict. It was not even a truce. It was pro-slavery and anti-slavery both, with the pro and anti aspects set up to operate in stages—favorable to the slave-owners in the short run, and favorable to the abominators of slavery in the long run. And nothing was odd about the arrangement.

Short-run, long-run paradoxes were the story of the American Revolution as a whole. The Revolution came to power in a society filled with feudal and aristocratic customs and legally endorsed religious bigotries of many sorts, much of which was left in place in the short run, and all of which was left exposed and vulnerable, in the long run, to the predictable logic of the republican project and its democratic implications.

As it happened, the long run, in regard to slavery, arrived quickly enough in the Northern states. But abolition’s spread into the South, which so many people had anticipated, failed to occur—because of the cotton boom, and the intimidating ferocity of the pro-slavery ideologues, and the skillful maneuverings of the pro-slavery politicians in national politics.

Still, Wilentz has a second large purpose in No Property in Man, after pointing out the battle over slavery at the Philadelphia convention, which is to observe that, in the following years, the national debate over that one question continued openly and officially, not just as a matter of social movements or what is called civil society, but in Congress.

The congressional debate persisted, not just in a small way, even during the administration of George Washington (who himself was one more contortionist Virginian on these matters). And from each decade to the next, the debate tended to revolve around the same original points, as if perennially trying to resolve the constitutional paradox, with one side pro-slavery, and the other side anti—and a range of people in the middle, trying to have it both ways. There were anti-slavery stalwarts in those congressional debates—Congressman James Sloan of New Jersey, Congressman James Tallmadge Jr. of New York, and others—whose names have disappeared from the national memory, perhaps because the tide of events flowed against them for a few decades, but who kept up the argument even so, now trying to prevent Louisiana from becoming a slave state, now trying to prevent an extension of slavery into the territories.

When, at last, the anti-slavery side began to prevail, it was precisely on the original basis, now presented for consideration to a wide public by popular agitators like Frederick Douglass (whose thinking had to evolve on the constitutional question, but did evolve), and subsequently by Abraham Lincoln. Douglass and Lincoln, both of them, tended, for political reasons, to oversimplify the constitutional complexities in anti-slavery directions—or so Wilentz acknowledges. But he judges their simplifications to have been more right than wrong. He admires the subtlety in Frederick Douglass’ remark that, even given the complications, the Constitution “still leans to freedom.” And Lincoln was a monster at hammering home the necessary points. He did it in his oratory and in his debates with the formidable Senator Stephen A. Douglas, the last national champion of the have-it-both-ways position, whose arguments, having come under a pummeling, remained on their feet for a year or two, and then went down.

It was a debater’s triumph. But—this is Wilentz’s point—the debater’s triumph did not represent anything new. Lincoln’s victory was the culmination of the argument that had gotten started in 1787—though, to be sure, in order to culminate the culmination, the word slavery finally did have to be inscribed in the Constitution, which took place in 1865 in the form of the 13th Amendment, prohibiting it everywhere.

IV.

I do not mean to predict too easy a success for the several contentions in Wilentz’s book. A couple of obstacles do stand in the way, beginning with a pesky difficulty that was introduced by the Constitutional Convention itself and generally by the founders of the republic. This was the decision to express themselves in a language of law, instead of a language of Enlightenment philosophy or of philosophically influenced theology. The language of law is designed to mandate procedures and to clarify them, and not to express ideas or describe realities. The result of this choice has been to condemn the whole of American political culture to a certain kind of inarticulateness, as if with tape over the mouth.

We have been living through a frustrating example of this phenomenon just now with Robert Mueller, who, on legal grounds, has refused to tell us straight-out what we have wanted to know, in favor of besieging us with hundreds of pages of disconnected details. And so it was in 1787. One of the anti-slavery stalwarts at the convention was Gouverneur Morris of New York, who called down “the curse of Heaven” on states where slavery prevailed, and who declared, he and another delegate, a “moral repugnance,” which must have set off quite a vibration in a room filled with arrogant slave masters.

But mostly the debate at Philadelphia stayed on a narrowly legal path, and likewise the congressional debate over the decades. And downward veered the narrow path into the caverns of committee work, subcommittees, new committees, and quibbles over language, until the black depths of a still more perfect inarticulateness were achieved, and euphemism (“persons”) and a legally-significant silence turned out to be crucial elements. It is dismaying. It makes for a chronology of murky disputation that is a lot less exciting than a history of slave revolts and underground railroads and the oratory of the immediatists, who enjoyed the freedom to shout themselves hoarse.

Here is the problem that has always beset even the greatest of the American historians. The actual history of the country is thrilling. It is the story of democracy, or, as Wilentz puts it in the title of his principal book, The Rise of American Democracy. But the choice was made, back in 1787, to wrap the thrilling history in a language that, for 222 years now, has ushered Sleep on winged feet into the reading rooms of America. Lincoln was a great president not only because he did the right thing, but also because he knew how to explain why the right thing was right—though even Lincoln watched his words.

But there is a larger and probably insuperable obstacle to clarifying and refining our sense of the history. Even if we grant that some of the founders of the republic and the congressional abolitionists from the early generations were nobly intentioned people, and, even if we grant that, in the face of great difficulties, they never relented, our hearts sink anyway. It is because, in the end, those people agreed to participate in a system that incorporated the enslavement of millions of people, and we simply cannot sympathize or nod in approval. The people we approve are the slaves themselves, plus the handful of immediatists, whose phrasing was sharp, even if their practical contributions were fuzzy. Ultimately we are bound to feel that, between those times and ours, a wall has arisen, consisting of a moral advance, and we are the beneficiaries of the advance, and, in order to look back on the events of earlier times, we have to peer over the wall, which is difficult to do.

That is the obstacle. It has the look of a major obstacle. And yet, it is a curious obstacle. What leads us to suppose, after all, that we are morally advanced, compared to the early generations of the American Revolution? The early generations disturb us by having agreed to abide and even to profit from utter horrors, but it may be that we ourselves are not above such a practice, with the difference being that, in our case, we make a system of averting our eyes.

Half a century ago, Americans bought their sea food from fishermen who labored under conditions of, at least, freedom. Today we obtain a percentage of our seafood products from an East Asian fishing industry that relies, in some degree, on slave labor—a shocking reality that was revealed by, among other journalists, Ian Urbina in The New York Times a few years ago (which is a basis, I presume, of Urbina’s about-to-be published book, The Outlaw Ocean). But well-meaning Americans are not aboil with outrage about the fish that they eat.

Half a century ago, Americans bought their clothes from manufacturers whose factories in New York and Los Angeles and other places had fallen under the control of the garment unions, which meant that Americans could feel generally confident about the labor conditions under which their clothes had been made. Union labels were sometimes stitched into the clothing, as a point of pride. Today we prefer to buy clothes that have been manufactured in Bangladesh or Vietnam. This, too, does not upset us.

If it did upset us, we might find it easier to glance back at the Revolutionary era and the early decades with a more sympathetic eye—with an appreciation that dreadful compromise is the human condition, and no one is excepted, not even us. It could even be that, if we gazed back sympathetically, we might begin to suspect that a good many of the people of the Revolutionary era and over the next decades displayed a sharper acuity on moral themes than we ourselves tend to display, and felt a deeper repugnance, in Governeur Morris’ phrase, to the extremes of oppression than we tend to feel, and showed, in any case, a superior commitment to what Wilentz calls “organized politics.”

Circumspection is not the modern style, though. We lack the necessary historical imagination. Putting it another way, our problem is bourgeois smugness, an old story. Bourgeois smugness, in my definition, consists of moral loftiness conjoined to a zest for low prices. It amounts to a skill, which allows us to gasp admirably at the horrors of the past and continue shopping in the afternoon.

Is there an antidote for this sort of thing? An appreciation for serious people is the antidote. Wilentz’s book attends to political arguments and legal positions more than to personalities and individuals, but, even so, some remarkable individuals do wander across the page. I am struck by the New Jersey and New York congressmen and other stalwarts from the earliest years of the republic, less famous and more glorious than James Madison, who insisted on putting up a congressional fight against “property in man,” even when they knew that, for the moment, their cause was hopeless—insisted on putting up a fight out of a conviction, I suppose, that, under the bright sun of the Revolution and its Constitution, good arguments would eventually turn out to be effective arguments. Or I do not know why they insisted on putting up a fight—but they did insist. Their portraits should go on dollar bills.

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.