Isaac Bashevis Singer’s Treatise on God

In a recently discovered manuscript, the great writer reflects on the good and evil within the divine

Isaac Bashevis Singer is known for his storytelling, whether in short stories, novels, memoirs, or stories for children. But he was also a thinker with a strong yearning for faith that was always in conflict with his intellectual doubts. Singer spent many years working out his own position on the various elements of religious life—divinity, tradition, custom, ritual, piety—discussing them in hundreds of articles that he published in the Yiddish daily Forverts, and deploying them to varying degrees in his numerous characters.

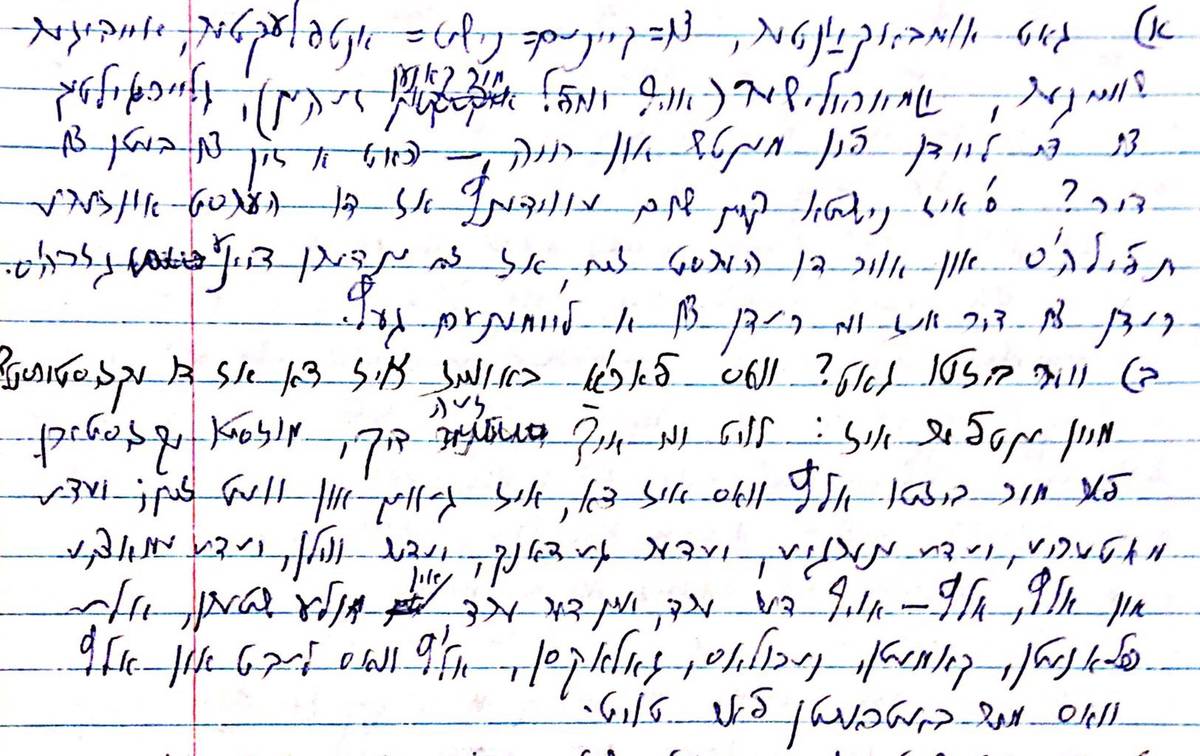

But there is another layer to Singer’s thinking about the crossroads of spiritual and intellectual life in handwritten manuscripts. This material, which presents Singer’s ideas at their most raw, has slowly begun appearing in translation, starting with a 1952 Hebrew prayer published by Tablet earlier this year. The piece published here, which was also found in the Singer papers at the Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas, lacks any identifying marks as to when it might have been written, though it appears to be long after the prayer. One clue is the phrase, “Everything—you are my God and my idol. I will ascribe to you the attribute of mercy.” In The Penitent (1983), published a decade earlier as Der bal-tshuve, Joseph Shapiro says to Pricilla, a woman he’d met on an airplane some weeks earlier, “If there is no God, or if God is amoral, then I want to serve that idol who is supposed to be moral, who loves the truth, who has compassion for people and animals.” There is a subtle difference between Singer’s own words and the words of his character. Publicly, he focuses on the idea of protest as a religious act, as in his author’s note to The Penitent, where he writes, “although I believed in God and admired His divine wisdom, I could not see or glorify His mercy.” Privately, it seems, he developed another approach, one more often expressed by characters in his stories than by his stated position as an author.

Singer never intended to offer any solutions to the quandaries of faith. But he did develop a personal wisdom, formulated in clear language, in which this conflict was embedded. His treatise on God goes further than any known text in expressing the degree to which his conception of divinity combined both evil and benevolent forces—bringing biblical, Talmudic, and kabbalistic modes of thinking together with a modern perspective on human history, the supernatural, and the cosmos.

Yet it also lays out his connection between religious thinking and literary fiction. “I will try to do what others before me have done,” he writes, “to turn you into a game and to play it for my own satisfaction.” This game, for him, is the game of literary fiction, and here we have evidence of Singer’s conception of literature as a spiritual practice. Beyond this, Singer’s treatise is also a personal cry, like Job’s, to a God that he insists must, in addition to everything else, have some measure of mercy toward the creatures that live on this planet.

—David Stromberg, Jerusalem

Untitled (Treatise on God), Incomplete, Date Unknown

1. God unknown, unrevealed to anyone, eternally silent, amoral (as far as we can see), indifferent to the suffering of humans or animals – is there any sense in pleading with you? There exists no evidence that you hear our prayers, and, if you do hear them, that they change your decrees. Speaking to you is like speaking to a clay idol.

2. Who are you, God? What proof is there that you exist? My answer is: as I see you, you must exist. For me, you are everything that is, was, and will be; all matter, all energy, all thought, all will, all emotion, and every single thing on the earth and in the earth, and all the stars, planets, comets, nebulae, galaxies, everything that lives and everything we consider to be dead.

3. You are time and you are space, you are the categories of our thinking and you are the thing-in-itself. You are consciousness and unconsciousness, cause and effect, faith and doubt, what we call reality and what we call dreams. You are the web of all our fantasies, every will and whim. In you roars the lion and hisses the snake, in you the righteous cries out and the evildoer laughs. In you Moses wrote the Ten Commandments, and in you Genghis Khan and Chmelnitsky and Hitler buried children alive.

4. Since you are everything, nothing can be outside of you. Everything cannot be increased, it cannot be doubled, and it also cannot be split. Everything has no boundary, no beginning and no end. Everything can have no cause, since the cause of everything would also belong to everything.

5. The great Jewish thinker Baruch Spinoza tried to ascribe two attributes to you that we as humans know, and an endless number of attributes that we know not. But what can the human mind know about everything? What can language express about everything? We know nothing more than the images or the dreams of our consciousness, all of us according to our own little thoughts, our bits of experience. Our mind isn’t built to comprehend everything, our language has no words for everything. Anything we say about everything, we say about ourselves, our senses, ideas, concepts, our sense of continuity, the dreams we dream by day or by night.

6. We dream that we’re alive; we dream that our dear ones are dead; we take medicine to extend our dream that we’re alive; we lament those who we believe no longer dream our dream, or no longer dream at all. We cry from pain and laugh for our pleasures and we are horrified that soon both will end, and sometimes we comfort ourselves that, no matter what happens to us, we will nevertheless have been a moment in eternity, a line, a page, or a chapter in the endless work that we call everything or God.

7. In God, we say, nothing can be lost. In God, yesterday never left, and today’s still here. In everything, there’s no place for loss. The time of everything is the past, present, and future – this is dictated by the reasoning of our dreams.

1. God of everything, I neither know you nor have any hope of knowing you – your divine thoughts, your essence, the purpose of our existence, if there is a purpose, the meaning for our suffering, if there is a meaning. But I maintain the right to dream of you, to fantasize about you with my tiny mind, with my spark of life. If you are everything, I tell myself, then I – an infinitely tiny part of everything – cannot be completely blind, cannot be only lies and deceit. Some trace of truth can exist even in my illusions and false conclusions. If I cannot truly know God, let me play with God, like a child with its playmates. Isn’t this what the philosophers have done? Isn’t this what religious thinkers have always done? They turned you into a game and ascribed to you all kinds of made-up and arbitrary virtues. They called you by all kinds of names. Some convinced others – and themselves – that you showed yourself to them.

2. Some say you are fire, and some that you are water; some have carved you out of wood, and some have abstracted you using logic; some have portrayed you as an almighty power that can create the cosmos with a word, and some as a dummy bound by his own rules; some have slaughtered others for you and your satisfaction, and some have themselves gone to the pyre for you.

3. Since you are, as I propose, everything, is it possible that no one has ever been completely wrong, and certainly no one has spoken the complete truth.

4. I will try to do what others before me have done: to turn you into a game and to play it for my own satisfaction. Since you are everything, and nothing can be outside of you, my game is you too. God of everything, in you is my faith, and in you are my doubts, in you are those who deny your existence, and in you are those who supposedly know all your ways.

5. God who brings death and life, brings down darkness, yet raises up. You are our correct conclusion and false conclusion, our truth and lies. You worship the idols and you worship yourself. You are the wound and the cure, the illusion and the reality, the murderer and the murdered. You are the fooler and the fooled. You are the hope and the disappointment. You are the dust on the surface of the moon, the center of the sun, the highest heat and the most absolute cold.

6. You are the natural and the supernatural. You are the law and the miracle. You are the Jew who digs his own grave, and the Nazi who mocks him and his situation. You may have countless attributes, or you may have no attributes. You are the monad of all monads, and blind will. You are the scent of the rose and the stench of the refuse. You are the plan and the chaos.

7. Can I pray to you? Do you hear my prayer? Can you help me? Perhaps you can, but don’t want to? Or you want to, but can’t? Do you know that, as things are, so they should be, or are you, as the materialists assert, an inanimate God, without thoughts, without goals, a cosmic inkwell which has been poured out and which has poured for so long that it wrote the universe?

8. So to whom, then, should I pray if not to you?

9. I’ve assumed for some time that you are not blind, but that you see. You aren’t deaf, you hear, you aren’t inanimate, you’re alive.

10. If everything is alive, I tell myself, death is nothing more than that part of life to which we have given the name “death”; if everything thinks, then there’s a spark of thought in the dullest of dummies.

10. [sic] Everything – you are my God and my idol. I will ascribe to you the attribute of mercy.

11. If everything is cruel, can it have a merciful essence? Might everything be a collective of an infinite number of idols, among which there is one called mercy?

12. To you God, or idol, of mercy I will say my prayer.

13. To me ...

Translated by David Stromberg

Untitled (Treatise to God), Fragments, Date Unknown © 2021 by the Isaac Bashevis Singer Literary Trust. Translation © 2021 by David Stromberg. Used with permission of the Susan Schulman Literary Agency.

Isaac Bashevis Singer (circa 1903-1991) was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1978.