Three Female Israeli Artists Use Buried Personal Histories to Counter Zionist Myths

Michal Baror, Tamar Nissim, and Maya Zack go digging in archives

Between May 24 and Nov. 5, 1948, kibbutz Yad Mordechai in Southern Israel was abandoned. The communal rooms, cowsheds, lawns, dining hall, kindergartens, and yards were emptied of their inhabitants, forced to evict by an occupying Egyptian Army. This was the height of the 1948 War, which later ended with an Israeli victory. The comrades found a temporary shelter in a nearby estate, owned by Ali Kassem Abed El-Kader, a Palestinian informant collaborating with the Jewish resistance organization, Ha’Hagana (Defense). El-Kader was later suspected to be a double agent. He was executed, his family was deported and his property was appropriated by the state.

When members of the kibbutz returned to their derelict lands in Yad Mordechai, they realized that their Palestinian neighbors had disappeared. All that remained was forsaken objects, which no one ever returned to claim. These objects, their histories and movement between spaces, became the focal point of a visual and contextual research conducted by artist Michal Baror in the kibbutz archive. This is one of three exhibitions by female artists that opened simultaneously in Israel this summer, which subvert official narratives by exposing personal testimonies. Crucially, these projects, by Baror, Tamar Nissim, and Maya Zack, begin in archives created by states and organizations such as kibbutzim. Each meticulously highlights the ways in which communities remember contested histories.

Commissioned by curator Ravit Harari to create an exhibition at the local gallery, Baror became intrigued by what she identified as a gap in the archive: a silence surrounding these six months and the ensuing status of left-behind objects. Exploring these objects, she outlines a complicated story of displacement. Although the kibbutz began amassing archival documents, photographs and meeting agendas already in 1943, the comrades avoided documenting their time away from the kibbutz. Baror located photographs, items and remnants of private recollections kept in private spaces. “I was looking at objects around the kibbutz, focusing on artifacts that might seem insignificant, believing in their silent testament,” Baror wrote in an email exchange. “Yad Mordechai’s narrative is tightly coherent, like any story told numerous times. It is written on signs across the kibbutz, in biographies, in the kibbutz notes and in history books. It arises in every conversation, like oil emerging on the waters, fabricating glistening surfaces. When I listened to the story telling itself over and over again, I felt a choir was accompanying the speakers, like ghosts chanting, blending in their voices. Only by obscuring our view or looking sideways could we uncover deviations from the story, and see cracks that might not appear as such to those who do not wish to recognize them.”

The question of Jewish refugees and their changing status is also central to Operation Baby by artist Tamar Nissim, shown at Ha’Kibbutz Gallery in Tel Aviv. Here, the artist uncovered testimonies and archival documents outlining the evacuation of 8,000 Jewish residents from kibbutzim in 1948, mostly children and civilian women. This project also began in the archive of kibbutz Yad Mordechai. “I arrived at the local archive to learn more about the eviction,” she shares in an email, “After the kibbutz recreated the event, and repressed traumas surfaced.” Although testimonies were captured in video, it was actually a text the archivist showed her in 2014 that triggered a new route for this project: Nissim read about a woman who left the kibbutz with her children, although travel was forbidden for security reasons. This individual act of disobedience suggested there might be other accounts waiting to be discovered. This became the basis for a video in which two women, portrayed by the artist, depict opposed positions regarding the evacuation.

Whereas Baror assumes the role of the artist-as-archivist as an outsider beholder, Nissim gestures toward central conflicts in kibbutzim and the Zionist movement by using her body. Seen in a field, standing tall, almost as though participating in a commemorative ceremony, dressed in periodical garments, the artist monologues the women’ dilemma: to fight for the kibbutz and let their children leave without them, or abandon the community for their young ones. The scene takes place next to a well-known monument, an abandoned tank at Yad Mordechai. Short, monotonous sentences reveal the women made different choices, and were forced to suffer the consequences of each.

In the inner space of the gallery, the viewers encounter testimonies told by contemporary children, who, like the artist, delve into the stories, and take on their physical presence. “The decision to work with written texts led me to different types of archives,” Nissim says. “I decided to focus on kibbutzim, since they maintained testimonies and letters written by children, as opposed to institutional archives that are concerned with the organizational dimensions of the evacuation. When I began to read the children’s words, I felt like hitting an unmediated, unfiltered, exposed nerve. I tried to imagine who were these children: when were they writing, what is the narrative hidden behind the texts, so over-burdened with national pride, and how did they process the trauma. I noticed some words repeated in different texts, and that they described similar events and experiences. I was particularly interested in ‘glitches’: the appearance of a youthful tone in texts that seemed to have been edited to fit the national narrative.”

The children in Nissim’s video read texts from books, as though taking part in an eerie story time. “This is Abu Shusha that was once our place and home,” a child reads, “We had friends there. We are now ruining it. Burning and destroying it. But not to worry, the kibbutz will be rebuilt.” The image of Zionism that emerges here is convoluted and fragmented, calling for empathy against a backdrop of endless battlegrounds, enemies from within and without: wars, crumbling nuclear families, failing national bodies and disobedient private individuals. “This child knows in 1948 what we needed more than fifty years to admit (although some still deny this): that there was a Nakba, and we caused expulsion and destruction,” Nissim says. “The possibility of identifying the mechanism of the Zionist narrative was for me like lifting a veil, allowing me to go back in time and understand that period better. The search in the archive resembles a procedure in which organs are seen exposed and bleeding on the operating table.”

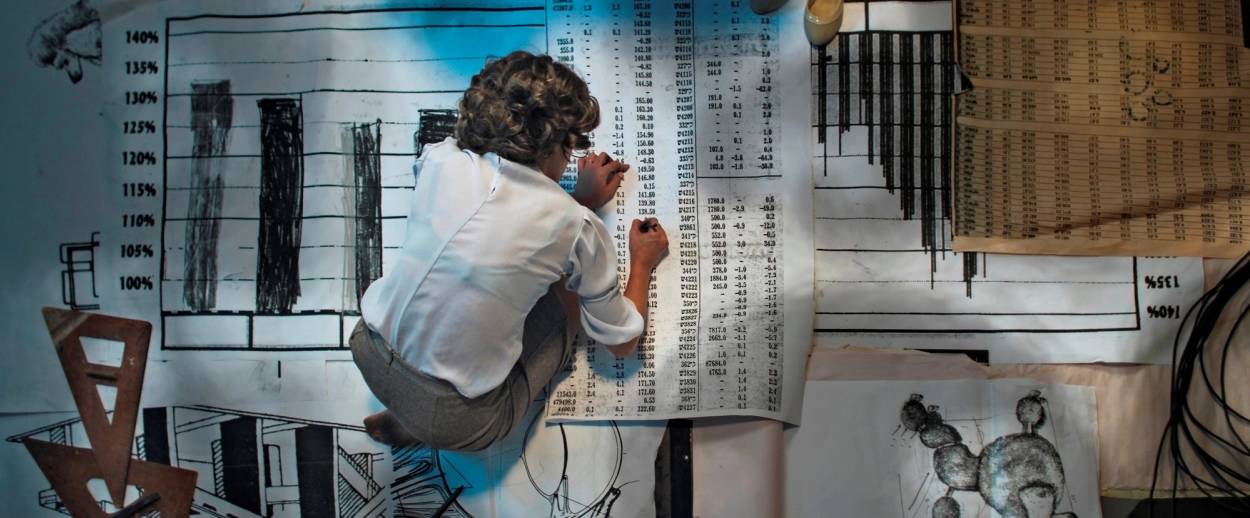

That visceral reflection on archival research suggests a connection between Nissim, Baror and Maya Zack’s recent exhibition. Zack presents an almost surreal exploration of the archive and its impact on identity in Counterlight, currently on view at the Tel Aviv Museum through Aug. 20, 2016. In a poetic, mesmerizing video work, large-scale illustrations and sculptural installations, Zack prefigures a female archivist who preserves the memories, ideas, and aspirations of Paul Celan: a pseudonym used by the Romanian born poet and translator Paul Antschel. His first book was published in 1947, after both of his parents died in a Nazi concentration camp; he himself was interned for 18 months. Zack therefore negotiates a different Jewish space than Baror and Nissim, another domain of national tragedy, which shaped an identity that Zionism later tried to erase.

Listening to Celan’s audio recordings in German, Zack’s heroine analyzes his archive in surgical manner, obsessively browsing through documents, maps and images, blurring boundaries between past and present, between her presence and the subjects of her research. She then becomes part of the archive, suddenly appearing in a photograph, and meeting Celan’s mother baking challah—an act that takes on magical qualities.

Traversing Jewish traditions, rituals and their manifestation in private and public domains, Zack investigates an eradicated cultural arena that would have been frowned upon by Baror and Nissim’s Sabras, who unexpectedly endured the experience of forced deportation. The vulnerability inflicted by their displacement, disclosed in private archives and testimonies, suggests a connection to Celan and his Diasporic heritage, which is seemingly opposed to national and physical ideals shaped by Zionism. Looking through the cracks, these artists uncover new ways to consider private histories and the public mechanisms that preserve them.

“Many things around us carry an excess baggage of pain and exile,” concludes Baror, “In that sense, I believe we have a responsibility in our research, to know what is around us, how did it get there, and how does its presence affect us.”

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

Rotem Rozental is an Israeli photo-historian, curator, and writer living in Beacon, New York. She is currently writing her dissertation about Zionist photographic archives.

Rotem Rozental is an Israeli photo-historian, curator, and writer living in Beacon, New York. She is currently writing her dissertation about Zionist photographic archives.