Jacob de Haan, Israel’s Forgotten Gay Haredi Political Poet

Assassinated for his opposition to Zionism, de Haan’s life was a succession of scandals, from sex with young Arabs to radical diplomacy

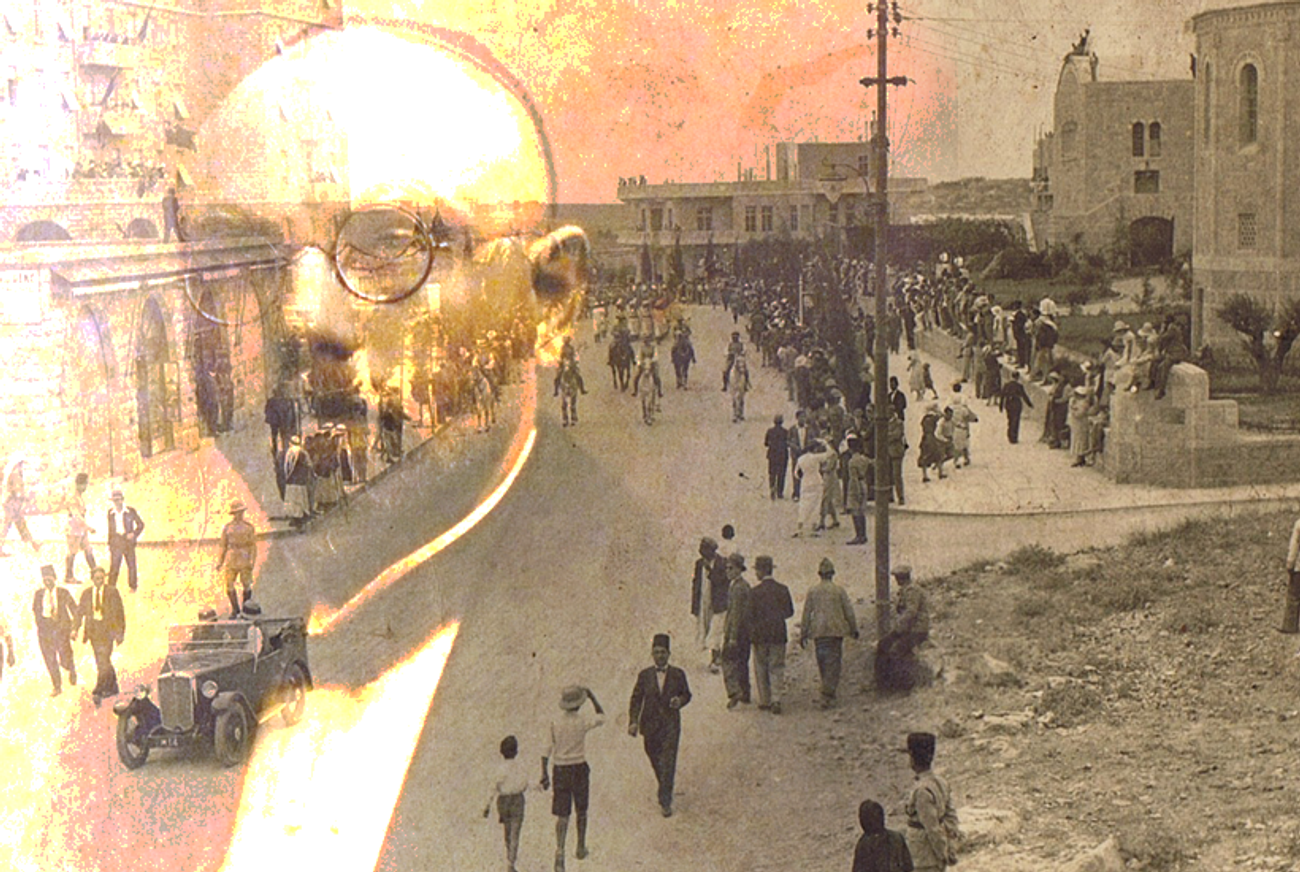

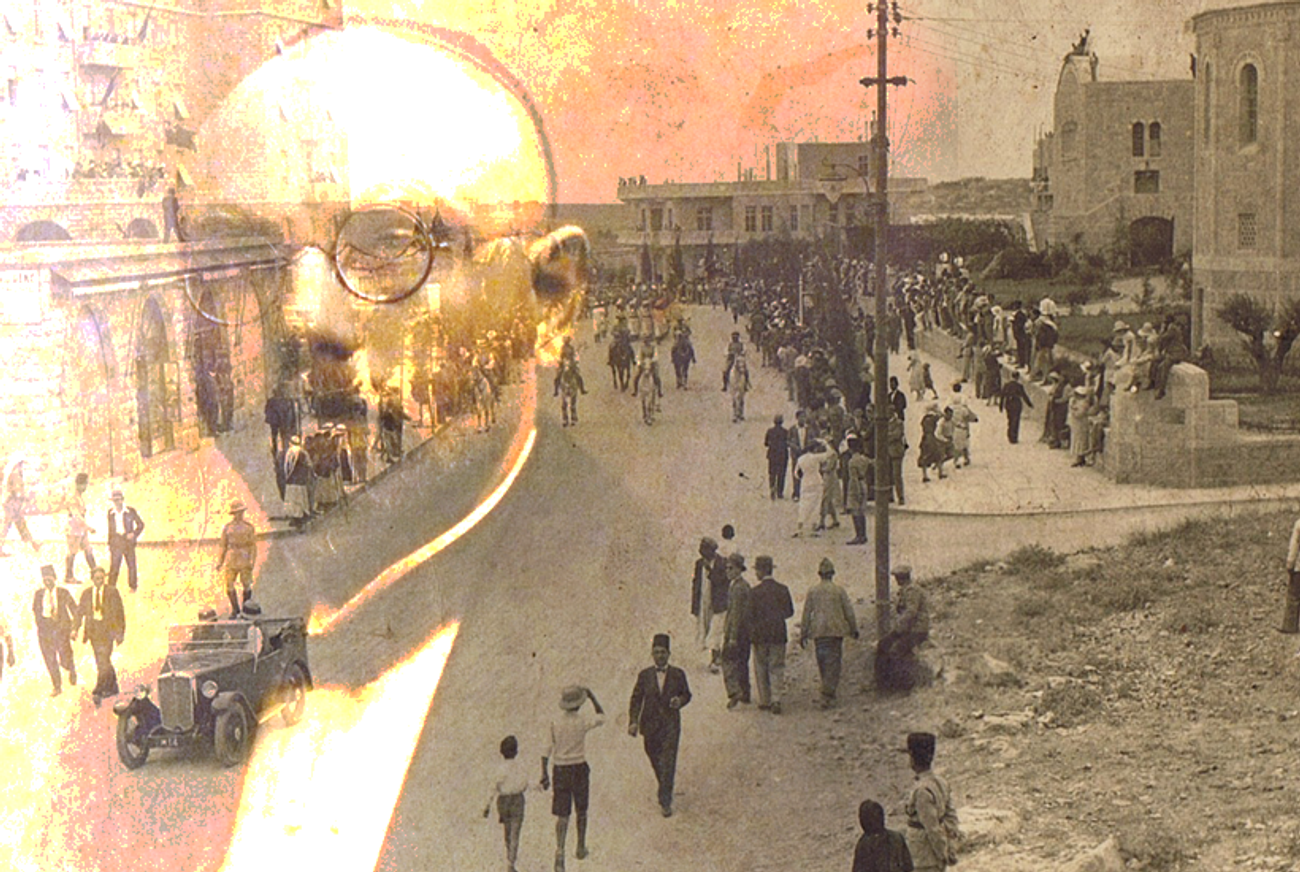

It was late afternoon on Friday, June 30, 1924, and the shopkeepers along Jaffa Road were rolling down the thin screens of corrugated metal and shutting down for Shabbat, shouting greetings at each other and slamming doors. The din didn’t seem to bother Jacob de Haan: Walking out of the makeshift synagogue in the back yard of the Sha’are Tzedek hospital, he stopped in front of the building’s imposing façade, lost in thought.

He had much on mind: The new book he had just published was scandalous, its 900 short poems much more candid than de Haan had ever been in print about his love for young Arab boys. And there was the upcoming trip to London, to convince the government there that not all of the Jews in Palestine were hell-bent on independence; the Zionists, incensed, had threatened de Haan more than once, but he didn’t care. His convictions, like his poems, were deeply felt. He started marching down the street.

A tall man, all dressed in white, approached him and asked him for the time. De Haan reached into his pocket and tugged on a thin gold chain, removing an ornate watch and straining to read its hands. The tall man reached for his own pocket and pulled out a long revolver. Just as de Haan looked back up at the tall man’s translucent blue eyes and his shock of black hair, three shots rang out, clearly audible even amid the noise. The tall man ran into a nearby backyard, his loose white shirt flapping in the breeze like a ghost. De Haan fell on the sidewalk, grasping his chest, bleeding. A few minutes later, he was dead.

Growing up, I often heard the story of de Haan’s assassination: He was the confidante and the right-hand man of my grandmother’s grandfather, the great Rabbi Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld, the leader of the anti-Zionist haredi community in pre-state Jerusalem. I’ve been to the spot where he was struck—the building now houses the state-run broadcasting authority—and tried to imagine him lying there, his magnificent and unending forehead against the cool pavement, looking up at the trees and the limestone walls, his vitality flickering, his breast wet and warm with blood.

But while I knew much about how Jacob de Haan died, I knew very little about how he had lived. When I finally bothered asking—reading old newspaper accounts and transcripts of interviews, sifting through my ancestor’s multi-volume biography, and perusing the surprising number of online tributes to a largely forgotten man now dead for ninety years—I understood why: a former communist, a contrarian, an Orthodox Jew, a secular intellectual, a terrific writer, a one-time ardent Zionist, a homosexual, a fan of the local Arab community—whatever fault lines divided Israel in the early years of its struggle to be born, de Haan seemed to embody them all. Somehow, it seems just right that he would be the victim of the Jewish community’s first-ever political assassination: To both the men who killed him and to those who supported him in life, some of whom were my relatives, de Haan was more convenient as a martyr than as a living friend or adversary. But in the snippets of his diary accounts that survived in archives, in his poems, and in the printed recollections of those who knew and cherished him, de Haan remains every bit as vibrant, as vital, and as impossible as he’d been in life.

*

Jacob de Haan was born in 1881 in a small Dutch town named Smilde. His mother came from a well-to-do family, but suffered from depression, delusions, and a host of other mental afflictions. His father was a foul-tempered cantor, butcher, and teacher who moved his family to Zaandam in the north when Jacob was young. As a boy, Jacob was sent to a heder and raised religious, but when he reached his teenage years he enrolled in a teachers’ college in Haarlem and cultivated his adolescent rebellion with a ferocity matched by few. He denounced his faith, moved to Amsterdam, joined the Social Democratic Party, and married Johanna van Maarseveen, a non-Jewish physician a decade his senior. Even more important, he fell in with a pride of bohemian psychiatrists who, as their colleague Freud was writing his ideas in Vienna, went much further in their assertions on the nature of the human psyche.

Frederik van Eeden, for example, his eyes intense and his mustache trapezoid, infused his writings with concepts he borrowed from the Hindus, believing we are all in possession of a manifestation of a universal soul, collective and eternal and glorious. Moved also by Thoreau, he established a commune called Walden, and lived there in squalor, helping for free anyone who sought him and writing convincingly about “lucid dreams,” a term he had coined. Another friend, Arnold Aletrino, found another path to controversy, becoming among the first physicians of the period to assert that homosexuality was not deviant but a wholly normal condition. Both van Eeden and Aletrino wrote irreverent novels and poetry, both of them preferring the bleak and the realistic over the prettily artificial: van Eeden’s famous work was The Deeps of Deliverance, a description of a woman succumbing in body and mind to the terrors of morphine addiction.

This frank discussion of vice made de Haan giddy. He had long noticed in himself what he considered abnormal tendencies. Working as a tutor, for example, he admitted that whenever he meted out punishment, he took a touch of pleasure from watching his young charges cry. He was soon writing as well, and was quickly acknowledged as a capable enough poet to merit a job writing for the Social Democrats’ newspaper. He published scores of poems, mainly for kids, about inspirational topics like the railway workers’ strike. But it wasn’t enough; de Haan needed to get personal.

Entitled Pijpelijntjes, or Pipelines, de Haan’s first book, published in 1904, was a sweet love story. “Give me a kiss,” says one of its protagonists in a typical passage, to which the other replies, “No and no. If you want it, you’ll come and take it.” The first protagonist smiles, saying, “We’re not doing anything bad; it’s just that I love you.” The protagonists, Joop and Sam, were both men, making the book Holland’s first published tale of homosexual love. If that wasn’t scandalous enough, Joop was a popular nickname for Jacob, and the book was dedicated to Aletrino, champion of same-sex desire. Soon, a rumor was spread that Pijpelijntjes was the autobiographical account of de Haan and Aletrino’s love.

Distraught, Aletrino alerted de Haan’s wife, and together they bought most of the book’s existing copies. When its publisher insisted on a second edition, Aletrino had the dedication removed and the characters’ names changed. But the damage was already done: Even in tolerant Amsterdam, the author of an explicitly gay novel could not hold any prominent position, and de Haan was fired.

He spent the next decade erring in the wilderness, sometimes mentally and sometimes literally. An impassioned crusader by disposition, he traveled to Russia and wrote a fiery book about the abysmal condition of its prisons. He went back to school, and received his law degree shortly after his 28th birthday. He dabbled as an attorney, and wrote two other books, Pathologies and Nervous Stories, both dense with homosexual affairs, sadomasochism, and other titillating stuff. His soul, however, was never at rest; it was missing, he felt, some great calling.

The Bitter Edge agreed. A biblical demon who first appeared to de Haan when the poet turned 30, The Bitter Edge would, de Haan wrote in his journal, “torture me, confuse my soul and my senses.” Above all, the demon wanted de Haan to find his way back into the fold, inundating the young man with messages of piety and teshuva, or repentance. One evening in May of 1913, strolling through an Amsterdam park at dusk, de Haan heard a childlike voice that he had never heard before. He stopped strolling and listened. “Return, oh Israel, to the Lord your God!” the voice said. “Return to me for I have redeemed you!”

It was all the convincing de Haan, already profoundly moved by his visions, needed. Before too long, and with the same fullness of spirit common to all of his pursuits, he once again became a religious Jew. In 1915, he published his new collection of poems; it was entitled The Jewish Song and contained none of the psychosexual provocations of his earlier work.

Thrilled with a talented writer so outwardly passionate about his faith, the Jewish community in Amsterdam embraced de Haan as a luminary. He was thrilled, but quickly realized that being married to a non-Jewish woman was a liability for his new round of reinvention. He asked Johanna to convert, but she refused; a proud agnostic, she saw all religions as fraudulent, and refused to affiliate herself with any. De Haan was furious. Frequently, he would humiliate Johanna, often in public. She forgave him every time.

Merely being a famed Jewish poet, even in a community as large and as vibrant as Amsterdam’s, was not quite enough for de Haan’s metaphysical appetites. He wanted more. He craved the tremors of a colossal drama, and was fortunate enough to find it with the Balfour Declaration, the 1917 letter from Great Britain’s Foreign Secretary to the Baron Rothschild confirming the British government’s commitment to establishing “a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine”: if a Jewish homeland was rising from the ashes of history, then de Haan needed to be there and play a part. In 1919, he wrote a letter to Chaim Weizmann, the declaration’s key facilitator, and announced that he was ready to join the struggle. He was, he wrote, “anxious to work at rebuilding Land, People and Language.” Lest Weizmann think that his correspondent was just another provincial laggard, de Haan took pains to describe his situation as plainly—and as grandiosely—as he could: “I am not leaving Holland to improve my condition,” he wrote. “Neither materially, nor intellectually will life in Palestine be equal to my life here. I am one of the best poets of my Generation, and the only important Jewish national poet Holland has ever had. It is difficult to give up all this.”

Cloaked in the thin veil of self-sacrifice, then, de Haan prepared for his departure. Johanna, it was clear, would stay behind, and her husband would make a living by writing the occasional dispatch for the Dutch papers, an assignment for which he was handsomely paid. He didn’t care much, however: as soon as he got to Jerusalem, he was sure, all he had to do was present himself to the leadership there and he would immediately become the fledgling community’s mightiest literary lion. On the day of his departure, thousands of fans crowded Amsterdam’s train station, waving frantically and singing “Hatikvah.” At least one chronicler of the occasion joked that many present just wanted to make sure that he’d really gone.

*

De Haan arrived in Jerusalem in February 1919, on a bitterly cold day. He had sent a telegram to several senior Zionist leaders, and expected a delegation of dignitaries to greet him at the station. None appeared. Under heavy rain, he found his way to the Hotel Amdursky.

Situated right across from the Tower of David, the Amdursky has long attracted a certain brand of mystic seeking revelations in the Old City. Staying there in 1857, Herman Melville described it as a “chamber low and scored by time, / Masonry old, late washed with lime / Much like a tomb new-cut in stone.” De Haan took his place in this tomb and waited for the rain to subside and for the Zionists to come calling. Neither happened, and a few days later, feeling wronged, de Haan presented himself at the Jewish Agency’s headquarters.

“I, the poet of The Jewish Song, place myself and my great capacity at your service, to build the homeland,” he told the junior clerk who finally showed up and agreed to meet him. The clerk sneered. “We’ll take care of the building,” he told de Haan. “You just make sure there’s cash in our drawers.”

Offended and disheartened, de Haan nonetheless resolved to remain in Jerusalem and work his way into the Zionist movement’s inner circles. The Zionists, however, were impervious to his charms: bespectacled, quick-witted, and excitable, with a receding hairline and a jumpy manner that reminded more than one observer of a frog, de Haan was far from the New Jew the men who populated the upper echelons of the Yishuv’s leadership had in mind. Two years after the Balfour Declaration, the Yishuv, the Jewish community in Palestine, needed farmers and soldiers, not self-aggrandizing poets who cracked jokes and spoke in foreign tongues.

While the Zionists rejected him, however, the British officers entrusted with the Mandate found him charming. He was playful, and had a manner of winning over, by sheer persistence, even those who did not like him. De Haan, one acquaintance sighed, just grew on you; as outrageous as he could be, he was impossible not to like. Not that the British probably needed much incentive to feel amicable: in a Jewish community thick with men and women busy being reborn as tanned and terse redeemers of the land, De Haan was, to the British, a more familiar creature, brainy and wordy and well-mannered. Soon, he was invited to all of Jerusalem’s parties. And no party was more socially essential than the annual Hannukah reception of Annie Edith Landau.

Miss Landau—no one ever seemed to call her anything else—was the closest thing the small and sun-bitten town had to a grand dame. She ran the legendary Evelina de Rothschild school for girls, which she transformed from a finishing school to a first-rate academic institution by reforming the curriculum, which had included only religion, sewing, and arts and crafts when she arrived, to which she added math, history, geography, and science. Eventually appointed an M.B.E. by King George V, she also ran her own salon, which drew representatives of all of Palestine’s warring circles. She was just as respected by the Orthodox Jews, whose faith she shared, as she was by the British administrators, her fellow aristocrats, and the Arabs, who saw in her a figure of dedication and grace. All three groups were heavily represented at Miss Landau’s annual Hannukah shindig, and De Haan managed to shock them all with a few cutting sentences.

“Two people can’t sit on the same chair,” he was said to have bellowed to no one in particular. “This land was given to us, and you”—he was now addressing a notable sheikh—“should take your wives and your children, load up your camels, and go away. The Arab lands are large, but here there’s no more room for you.”

So, at least, went the rumor that began circulating while the custodians were still piling up the dirty glasses and stacking up the chairs. Soon, it reached all corners of Palestine, making de Haan the small country’s enfant terrible. Which sounded strange to the man himself: De Haan had no recollection of ever speaking such lines, and didn’t precisely share the sentiments know so vociferously attributed to him. He set out to defend his good name, but discovered quickly that his version had few takers. The British authorities, pressured to show evenhandedness toward Palestine’s Jews and Arabs alike, launched an official inquiry.

De Haan, flustered, appealed to the Zionists to support him in his denial; not wishing to be aligned with the voluble and mercurial Dutchman, the Yishuv’s leadership refused, distancing itself from de Haan. It was a blow from which he would never recover. “Here,” he wrote in a dispatch at the time, “everything is wilderness and emptiness. Control lies in the hands of professional and materialist Zionists.”

Unable to forgo the strong romantic currents that had brought him to Jerusalem, however, he sought another object of infatuation, and found the city’s Arabs. The old pattern resurfaced: the Arab cause was now his obsession. Ever the polyglot, he quickly studied Arabic, and took great pleasure in upsetting the Zionists he’d meet by demanding that they speak to him in Arabic, an official language according to the British bylaws. He developed a similar passion for Arab politics, and sharply distanced himself from the Zionist cause.

The deepest expression of his newfound passions, however, was carnal. Arab men—very young men in particular—became his obsession. He wrote poems about men like Mahmoud the stable boy, being explicit about his lust. As always, he saw his stirrings in metaphysical terms. In one poem, entitled “Doubt,” he wrote: “The year sneaks in in God’s capital city / Near the Western Wall / Tonight, what is it that I long for? / The sanctity of Israel, or an Arab male prostitute?”

Taking residence with a well-heeled Jerusalem family, de Haan demanded that the family’s Jewish maid be barred from his quarters—she stole from him, he argued angrily—and hired instead a handsome young Arab man as his valet. Each afternoon, de Haan and his friend would lock themselves in the room. No one in Jerusalem had much doubt as to what the two were doing behind closed doors.

“Last week, I had a sort of adventure,” the future Nobel laureate S.Y. Agnon wrote to his wife. “I was looking for an apartment, and was handed from one Arab to another until I made the acquaintance of one Arab who spoke fluent Ashkenazi… When I told Mr. Greenhaut the man’s name etc., I was informed that the man was the good friend of de Haan, curse him, meaning his wife, darned devil.”

De Haan didn’t care much; he was no stranger to the wagging tongues of detractors. But, as always, he sought to align himself with a higher cause, and when Zionism failed him, he turned again to religion. O, more accurately, he turned to Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld, my great-great grandfather and the leader of Jerusalem’s haredi community.

*

Brilliant, ascetic, temperamental, and immensely charismatic, Sonnenfeld was as well-versed in the intricacies of world affairs as he was in the mysteries of the Talmud. When, for example, Tomas Masaryk, Czechoslovakia’s philosopher president, visited Jerusalem late in his career, he made a point of consulting with the hunched-over, robed sage.

Like de Haan, Sonnenfeld was a man of intricate extremes. He’d emigrated to Jerusalem from Slovakia, and was so moved by seeing Eretz HaKodesh, the sacred land, that he climbed on board the ship’s mast, vying for a better view. Once in Palestine, however, he became a fierce opponent of Zionism, which he saw as utmost heresy, believing, like most religious Jews, that it was strictly forbidden to try and “hasten the end” and that a Jewish homeland was only possible once the messiah arrived. It was a subtle contradiction: Sonnenfeld opposed Zionism with all his might, but would only do so once firmly ensconced in Zion.

Rabbi Avraham Yitzhak Kook had different ideas. Sonnenfeld’s close friend and main rival, Kook believed that Zionism’s stirrings may very well be the beginning of redemption, and that the muscular and secular pioneers in the kibbutzim were the unconscious heralds of salvation. In 1913, the two rabbis, accompanied by a few of their colleagues, rode mules to Palestine’s north to meet the young Zionists in person. Elated, Kook joined the tanned youth in dance; Sonnenfeld, distraught, wept. Upon their return to Jerusalem, Kook wrote enthusiastically in support of the Zionist ethos, even celebrating calisthenics as a mystical exercise that not only makes the body stronger but prepares the soul, too, for the holy task of building the Holy Land. Sonnenfeld, furious, published an essay accusing Kook of “praising the wicked.”

The two rabbis maintained a mutual admiration, but the stage was set for a fissure. Kook, naturally, was embraced by the emerging Zionist leadership, if not always unproblematically, and appointed Jerusalem’s chief rabbi. Sonnenfeld, sensing that his war was being lost, sought an ally with a gift for politics. De Haan was a natural fit.

When he first met Sonnenfeld, in May of 1919, de Haan wrote in his journal that the rabbi stood in stark contrast to the petty Zionist leaders who ruled the roost in Jerusalem, and that Sonnenfeld was as holy and devoted as the secular bureaucrats were narrow-minded and uninspiring. But even such deep admiration was not enough for de Haan; before too long, he was writing poems about his new shepherd, Sonnenfeld. “Above all, the Torah is his treasure,” went one of them. “From morning until evening, he desires nothing else. / Even though he is impoverished, his life is happy and secure / More than the lives of all those who revel and rejoice.”

Sonnenfeld was quick to make it clear that the admiration was mutual, admitting the Dutchman into his inner circle and appointing him his right-hand man. The confidence moved de Haan greatly: Here, for the first time in his life, was a man in a position of authority who recognized his genius and sought to reward him for it, with no caveats or reservations. In March 1920, de Haan was elected to the 70-member City Council for the Ashkenazi Community, the haredi community’s governing body, with the expectation that he would lead it into battle against the Zionists.

After a botched attempt at a coalition with the religious Zionists against the secularists, de Haan finally had a strategy in mind. The British, he knew, categorized the people under their rule according to their religious affiliation; as far as the Mandatory government was concerned, all of Palestine’s Jews belonged to the same ethnic and religious group, which, for convenience’s sake, was represented by the Zionist leadership, the best-organized Jewish group around. For His Majesty’s administrators, then, Jews were synonymous with Zionists. It was that assertion that de Haan sought to challenge.

Like a man possessed, he set out to convince the Brahmins in London that there was another Jewish community in Palestine, one that abhorred the idea of independence, one that was ready to make common cause with the Arabs, one that welcomed the crown’s continued sovereignty. He wrote long and eloquent letters to Winston Churchill, then Secretary of State for the Colonies, as well as to the Foreign Secretary, Arthur Balfour himself.

All that, however, transpired in private, and politics, de Haan knew, was one part procedure and three parts spectacle. He needed his big coup de theatre, and he got it with the visit of Alfred Harmsworth, the First Viscount Northcliffe, in February 1922. Publisher of The Times, The Daily Mail, and other newspapers, Lord Northcliffe was among the most influential shapers of the United Kingdom’s public opinion. So great was his renown that, during the Great War, the German Navy, exasperated by his tireless anti-German propaganda, sent a warship to shell his country home in Kent, killing his gardener’s wife. Northcliffe, it was known, was a man of great passions, fond of fast boats and car racing and women—he fathered his first child when he was seventeen, the mother being a sixteen-year-old maidservant in his family’s employ. A man like that needed to be engaged not with politics but with poetry.

The poet, de Haan, had the perfect plot in mind. He purchased a round-trip ticket on the train to Alexandria, the one he knew would carry Lord Northcliffe from Egypt to Jerusalem. Dressed in his finest, he boarded the train and paced around until he spotted his target. Then, as if by serendipity, he befriended the influential aristocrat, reciting some of his verse and, more important, regaling his new friend with tales of how terrible and cruel those dastardly Zionists really were.

When the train pulled into the station in Jerusalem, a committee consisting of the Zionist leadership’s brightest lights was there to welcome him. Banners were prepared, and the mood was festive. Then, however, the train’s doors opened and down walked Northcliffe, arm-in-arm with de Haan, shooting the Zionists a disdainful glance and walking right past their receiving line. It was a major blow.

Immediately, and with rarely paralleled vitriol, conspiracy theories started swirling. De Haan, went a popular one, had managed to convince his new friend Northcliffe to press Balfour into retracting his famous declaration in support of a Jewish homeland. “Traitors and provocateurs in the guise of Orthodox Jews,” wrote one Zionist newspaper, “are severing their nation with their tongues, teaming up with the Arab delegation in an effort to extinguish Israel’s last hope.” Other publications were not so subtle: a popular weekly magazine ran a poem about de Haan that left little room for interpretation. “The man is insane,” it ran, “and his villainy without end / And no one throws stones at him / And no one bashes him with a bat.” These last lines were not so much a statement of fact as a lament: to most Zionists, de Haan was despicable enough to merit a swift and violent end.

This burning hatred delighted its recipient. The same bureaucrats who failed to genuflect when he’d first arrived and offered his services were now in awe of his powers. He took pleasure in being Jerusalem’s most hated man. One day, showing a Dutch visitor around, de Haan encountered a group of people who, at the very sight of him, spat on the ground in contempt. De Haan’s visitor was stunned by the crude gesture. “They’re not doing this out of respect for you,” he noted. “No,” de Haan said gleefully, “they’re spitting on the floor out of respect for you! If I was by myself, they would have spat in my face.”

While some spat, however, others took more extreme measures. “I hereby inform you that unless you leave our country by the 24th of this month, you will be shot like a rabid dog,” read a note de Haan received in May of 1923. It was signed “The Black Hand.”

De Haan filed a complaint with the police, but he greeted the death threat with his signature gusto. Whenever making appointments now, he’d smile and add, “that is, if I’m not murdered beforehand.” On the May 25, the day after the ultimatum had expired, he wrote in his journal: “how innocent is the 25th when one is not assassinated on the 24th.” But with every day that went by, de Haan grew more convinced that the threats against him were idle, and that the Zionists hadn’t the guts to gun him down. It was time for his next act.

*

Early in 1924, King Hussein visited his son, Abdallah, in Amman, Jordan, eager to form a united Arab federation that would include all of Palestine. Recognizing Hussein as a powerful regional actor, the Zionist leadership dispatched a delegation to Amman to meet with the king and impress him with the necessity of Jewish sovereignty. De Haan put together a delegation of his own; to the Zionists’ great chagrin, Hussein received it with great fanfare. De Haan’s message, the Zionists knew, was one that the king was likely to endorse: the real Jews, went de Haan’s main talking point, had no patience for all that talk of independence, and would be His Majesty’s most loyal subject should he establish his kingdom and oversee the Promised Land. The Zionists tried to convince de Haan—desperately, angrily—not to meet with the king, but de Haan refused. He left his meeting with Hussein with a royal promise to take the haredi point of view into account, as well as with a sizeable financial contribution to a number of haredi institutions in Jerusalem. Even worse, de Haan returned to Amman a few months later, and convinced Hussein to sign a statement denouncing “the anti-religious Zionist movement as unjust towards Muslims, Christians, and Orthodox Jews.”

And now he was about to travel to London, the Zionists knew, to meet with God-knows-who and ask for God-knows-what. Reading reports about de Haan in the papers, Avraham Tehomi, a senior member of the Hagannah, the pre-state underground army, was livid. “I saw that we, too, had traitors,” he said in a later interview. “And not Communists, who, by their very nature, are traitors to their country, but a Jew organizing a crusade against Zionism.”

Tehomi was born in Odessa and emigrated to Palestine as a young man. Legend had it that upon his arrival, he walked from the port Haifa to Jerusalem, and then set up a tent in the holy city and lived in it for months. Even if not true, the story was believable: Tehomi was a tough Jew with a penchant for action, whose shock of black hair and burning blue eyes made just as much of an impression as his decisive demeanor. Soon, he found his way to the top ranks of the Hagannah, and, later in life, to the Irgun, the Revisionist movement’s military group.

As a senior Hagannah officer in Jerusalem, Tehomi began circulating the idea that de Haan should be shot. Among those he consulted were Yitzhak Ben Tzvi, the Zionist leader who’d eventually become the State of Israel’s second president. And while the precise details of just who had ordered the assassination are still, even after all these decades, unclear, there’s little doubt that many in the senior Zionist leadership in Jerusalem knew about the proposal to kill de Haan—and that none objected. And there is no doubt that Tehomi was put in charge of the operation.

In later interviews, Tehomi recalled that reading about de Haan’s travels to Amman, he was so livid that for days he could think of nothing else. But once he was entrusted with the operation against the Dutchman, he grew calm and focused. Meticulous in his work, Tehomi began following de Haan, studying his daily routine and mapping his usual routes. Before too long, he was ready. But the assassination of a fellow Jew was a tall and terrible order, and Tehomi felt he needed to allow de Haan one more chance to repent. He followed him to the Sha’are Tzedek hospital one afternoon, and sneaked into the pew directly behind de Haan’s.

“There’s a lot of bitterness towards you in the public,” he whispered mid-prayer. “We don’t understand what you’re trying to do. We came here from Russia after pogroms that killed many Jews. We came here to save our souls, and here comes a Jew like you and destroys our last place of refuge. What are you doing to us?” Stop doing what you’re doing, Tehomi concluded his hushed message, “or it won’t end well.” De Haan, however, was in no mood for a conversation. “Epikores!” he yelled at Tehomi, a word that connotes a Jew who’d abandoned his faith. Tehomi got up and, with de Haan still shouting, quickly left the synagogue.

The encounter left de Haan shaken. In typical fashion, he saw his poetry, his politics, and his persona as one indistinguishable drama. One of his friends recalled seeing him lost in thought; suddenly, de Haan looked up, speaking of himself in the third person, and said dreamily, “In a few days you will hear that Dr. de Haan was murdered.” He injected the same anxiety into his art. A new poem, called “Betrayal,” took the bullet as its central metaphor: “As a tender chick flies / So flies my poem / Until the gun / Shoots my heart.”

Sonnenfeld and other colleagues begged him to take precautions, but de Haan refused. He was sick, he told them, of living in fear. “I’m afraid of the past, because I can’t forget it,” he wrote shortly before his death. “I’m afraid of the future, because I can’t prevent it. And this is how I live in the present, like a tightrope walker. It must end in disaster.”

It did. On June 30, 1924, as he was walking out of the synagogue late on a Friday afternoon, a man in white walked up to him, asked him for the time, and shot him three times at close range. That man, most likely, was Tehomi. Asked repeatedly throughout his life if he was the shooter, Tehomi neither confirmed nor denied. Even before de Haan’s body was interred, however, the identity of the shooter became the subject of wild speculation. Who one believed had shot de Haan said everything about one’s politics: was it one of his Arab lovers? Was it a fellow haredi, outraged after having discovered de Haan’s homosexuality? Was it the Zionists?

Paranoia ran deep: senior Zionist leaders, including David Ben Gurion, blamed each other for the bloodshed, escalating their rhetoric, threatening more violence. The haredi community, too, was gearing for a fight. Hundreds attended de Haan’s funeral. “This murder,” Rabbi Sonnenfeld thundered at de Haan’s graveside, “was committed by the descendants of Jacob who acted with Esau’s sword and Esau’s craft in order to silence Jacob and Israel … Look at the abyss into which the heads of the Zionist leadership had tumbled and shout out loudly that you wish to be no part of this evil congregation.” After the funeral concluded, the throngs headed to the city’s center to confront the Zionists. The police just barely curbed the violence.

*

The storm, however, died down within a matter of weeks. Maybe it was the shock and the shame inevitable in a small, close community having suffering its first political assassination. Maybe it was the Fourth Aliya—the largest wave of migration the small Jewish community in Palestine had known—thickening the ranks of the Yishuv by more than 80,000 people and making the community larger, more diverse, and less apt to care about the arabesques of political infighting. And maybe it was de Haan’s new book, published very shortly after his death and rich with poems about his affairs with young Arab men, candid revelations that made him, in the eyes of many of his pious friends, a less-than-ideal martyr. Whatever the reason, the memory of de Haan soon faded away, his assassination a curiosity and the circumstances of his life largely forgotten.

Perhaps it’s only right. In a century of passionate and purist ideologies, de Haan straddled too many fault lines, embodied too many possibilities and potentials, and refused—even in his most fervent phases—to ossify into something dead and hard. He was alive in a way that the affairs of men could never really contain. And he knew it. In his final collection of poems, one poem accurately charts the course of de Haan’s life and afterlife: “I have fled God in the paths of lust / To where? To God, only to Him. / I wish to return to my Godless life / And God, and only he, will secure my return.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Liel Leibovitz is a senior writer for Tablet Magazine and a host of the Unorthodox podcast.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.