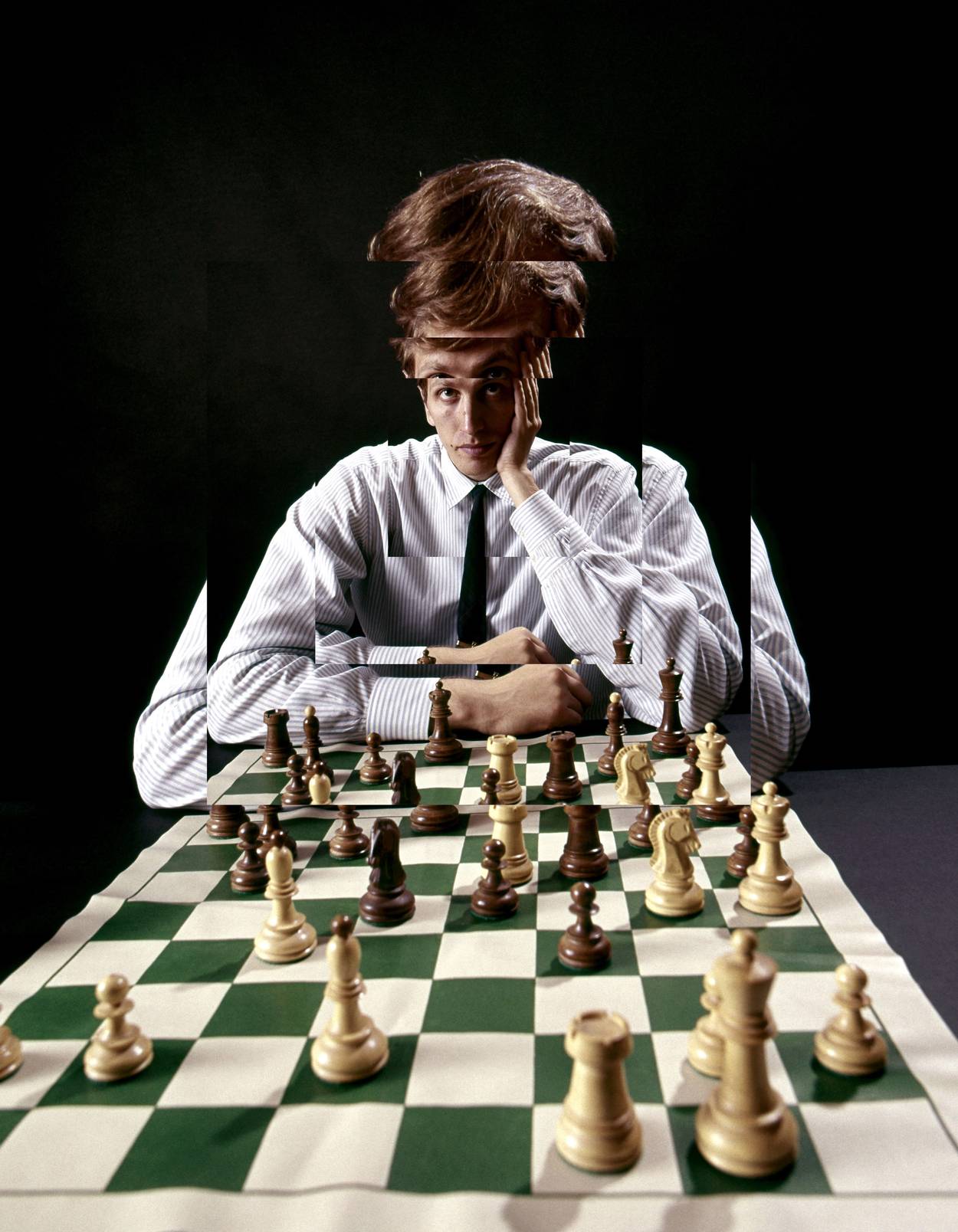

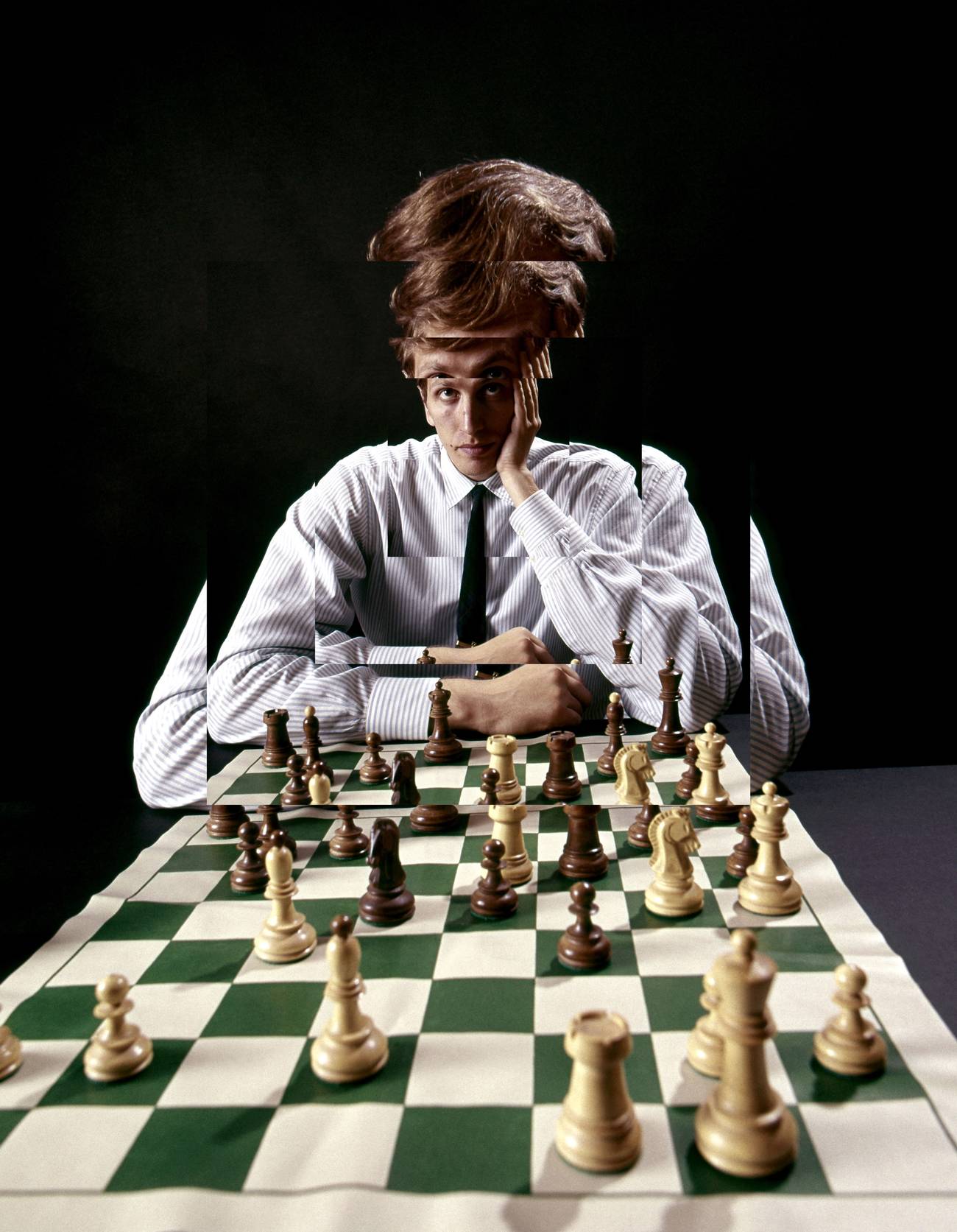

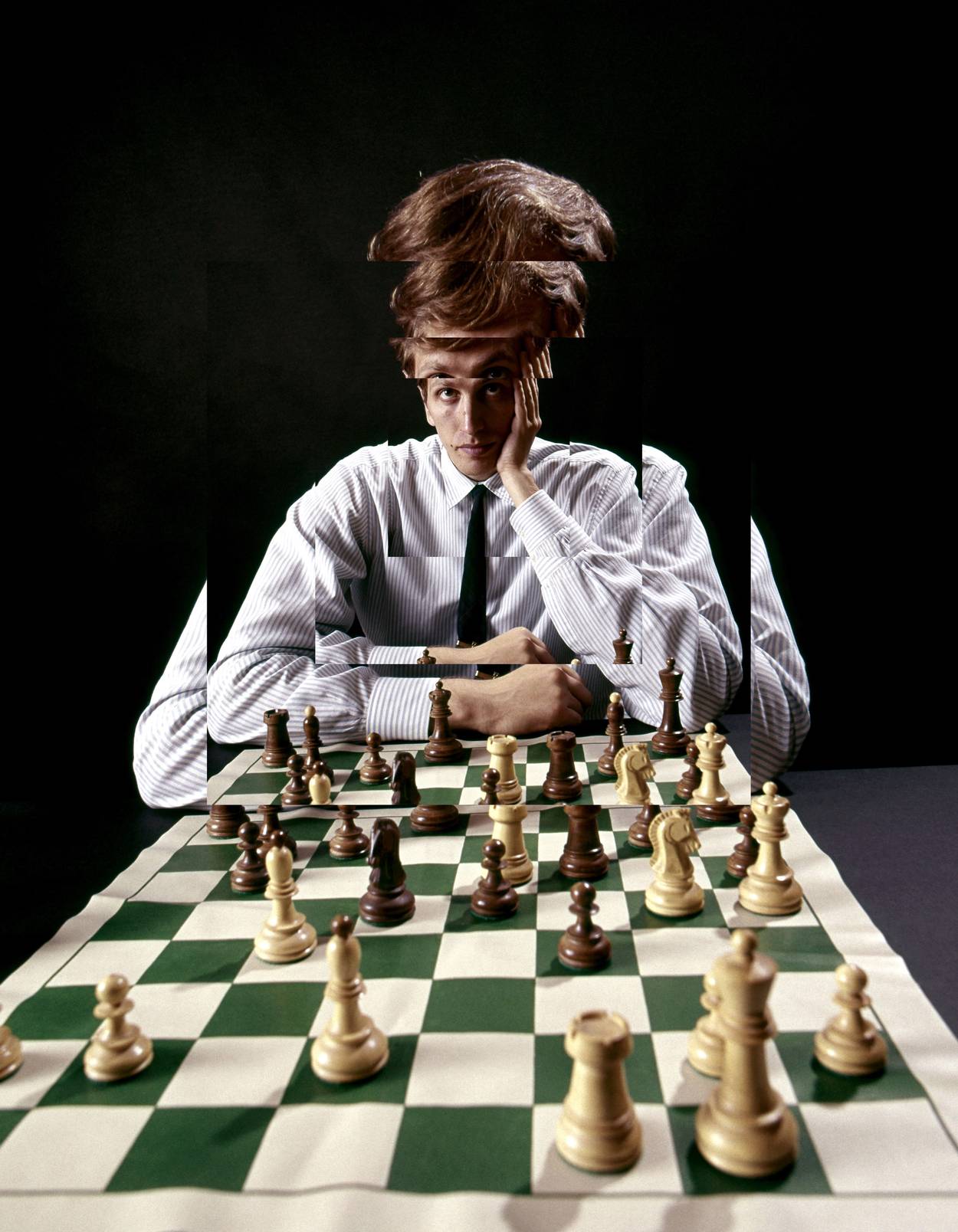

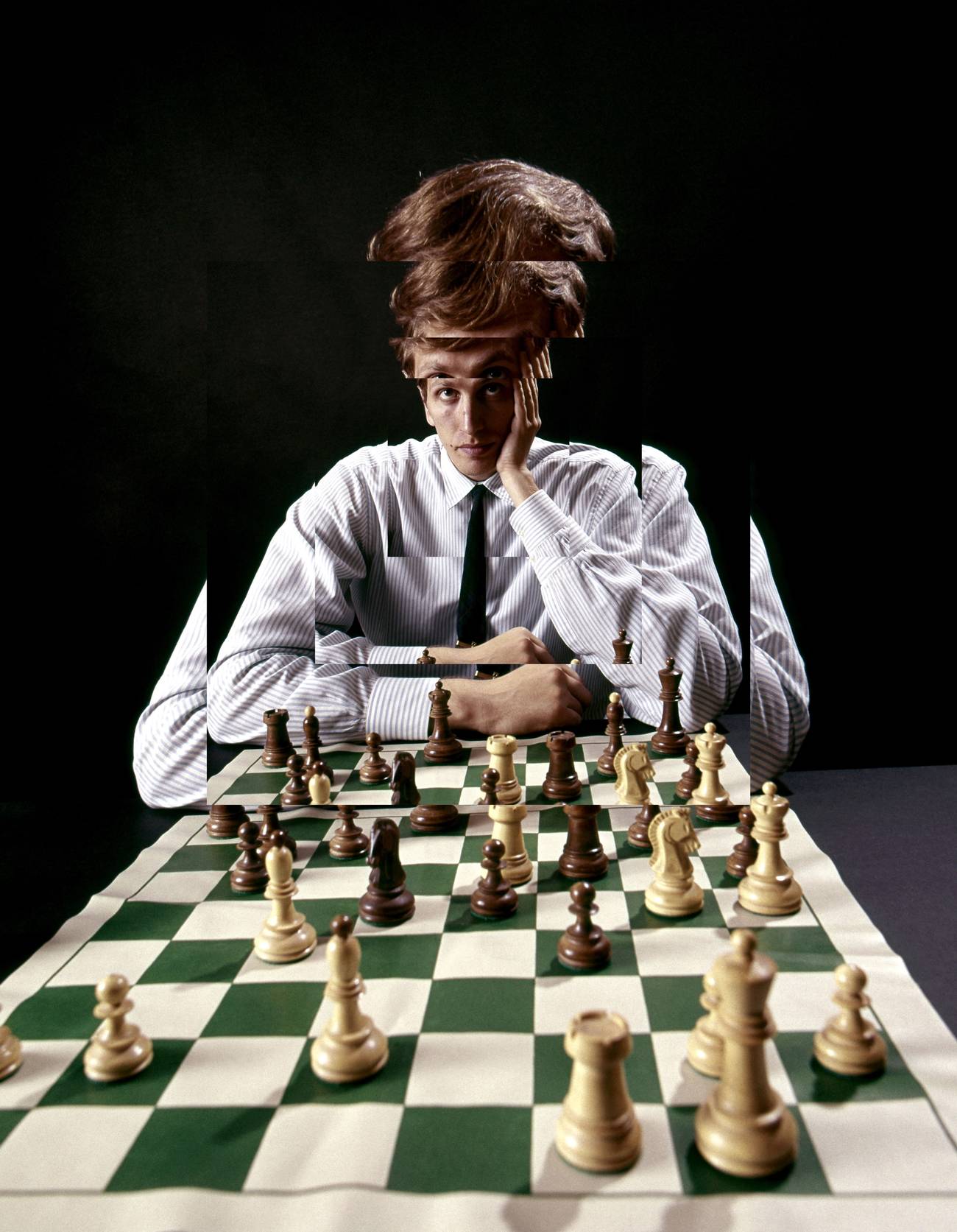

Bobby Fischer’s Greatest Moves

A chess master, reimagined, corners himself

1.

On Sept. 11, 2001, Bobby Fischer, the former world chess champion and perhaps the most brilliant mind that this highbrow sport has ever known, gives a passionate interview to a Philippine radio station: “That’s fantastic news. It was time for those disgraceful Americans to have their heads knocked. It’s about the time to finish with the USA once and for all!” Some people already knew his eccentricities and qualms. They already knew about his infamous beliefs and senseless actions. But no one would ever expect such a statement from the American idol, especially at such a shocking moment for the world.

Bobby, still in a frenzy days after the destruction of the Twin Towers, sends an open letter to his new “friend”: “Dear Mr. Osama bin Laden, I would like to introduce myself. I’m Bobby Fischer, the world chess champion. First of all, I would like to say that I share your hatred for the perverted and murderous state of Israel and its main sponsor, the USA—that Jewish-controlled country, also known as the ‘Jewnited States’ or ‘Yiddishland.’ And we also have something else in common: We are both fugitives from the terrorist system of American ‘Justice.’” What would have led the great chess champion to make these statements? Where did all this abomination come from? How can one understand the mind—as much enlightened as it is crazy—of this American Jew, who became a national hero and the symbol of a whole generation?

Bobby Fischer seemed like a normal child. He smiled, joked, and connected with everyone around him. He was loving, polite, and had a good sense of humor. He valued the presence of his mother and sister, but always suffered from his father’s absence during his childhood. He always wondered where his father was. Why did his friends at school seem to have structured families, and he didn’t even have a father to play with? Why did his mother work so hard and cry so much? What did he do to make his family become like this?

Bobby lived in the shadow of that guilt, that heavy burden, that pain caused by the endless search for a father’s gaze, a gaze he would never find. He witnessed the suffering in his mother’s eyes, always distant, always sad, always exhausted. All this was very hurtful for him. His pain was so great that, at a very young age, he had to find another world to escape from his parents’ impotent eyes. It was then, at the age of 5, that he discovered and became seduced by the subtle and thoroughly alienating art of chess. His most serious delusion. His most fervent passion.

His mother suffered from the anguish and the dissatisfaction of the Jewish diaspora. She was a descendant of Polish Russian Jews who arrived in America, fleeing the pogroms, in search of an unexplainable dream. She was a very clever woman, highly educated, who had studied medicine at one of the most prestigious universities in Moscow. She spoke seven languages fluently. She supposed she would have a brilliant future ahead of her. She longed to be part of the society, culture, and soul of her beloved city. Unfortunately, she never really belonged to that country. She was never accepted there. She was persecuted and threatened like most Jewish people who were either brave enough to remain in that country that always saw them as foreign, or they fled to another place where they imagined they would be welcomed. And so, the option was: to stay in Russia and very likely die there, or to leave, chancing everything on luck and fate. Because of a surge in the persecution of Jews in the early 1930s, she decides to flee. She arrives in America holding tightly on to her socialist convictions.

She and her group of intellectual friends dreamed of a world in which religion would have no importance at all. There would be no distinctions of class, creed, or culture. Everyone would be equal, members of a single human race. The Jewish question should be forgotten, since everyone would be equally accepted in an ideal model. And so, she fought for those ideals, but she ended up being punished for something she didn’t even believe she was apart of. In reality, some people were less equal than others, and she had to accept that and leave.

In her new home, she had to be content with merely surviving. Now she was a foreign citizen, with a different history, a different language, and a different culture. A highly accomplished woman, an ex-medical student who now has to undertake any job just to make ends meet.

She arrived with her daughter, Joan. She had married a German citizen named Hans-Gerhardt in Moscow, but he had never been allowed to enter the United States. When she arrived in America in 1942, she was pregnant with Bobby. On the birth certificate, Hans-Gerhardt appears as the child’s father. This ungovernable child will never know for sure who his father was. But for years he would dream of meeting him.

His mother, upon arrival in America, would meet the Hungarian physicist with whom she had an affair before Hans. His name was Paul Nemenyi, also a persecuted Jew from the diaspora, and he was Bobby’s biological father. An equally absent father, like the German who registered the paternity.

At the age of 5, his sister, through an irony of destiny, receives a chess board as a gift from the corner store where they lived. She is surprised by her brother’s reaction and interest in the gift. He feels drawn by the power of that fantastical kingdom in front of him, where the survival of kings, queens, bishops, and knights would all depend on his own effort. He realizes that the excitement, security, and ultimately the triumph of the kingdom would be his entire responsibility: Nothing external or accidental could alter that scenario. This new game of magic and fantasy becomes an obsession and a source of profound joy for that particularly sensitive child. Would this be the only way he could alienate himself from reality? From persecution? From discrimination? From the absence of a father? From his mother—scholar, doctor, polyglot—who constantly had to submit herself to humiliation just to feed her children? Bobby was at the forefront of a new world with billions and billions of new possibilities. And all the glory and ecstasy of this new world would depend exclusively on him and his creativity.

Over the years, chess becomes Bobby’s entire world. He searches everywhere for books, games, and opponents of his level. All he can think about is chess. Every night he discovers himself in one of the 64 pieces of his heaven. He dreams of great conversations with the bishop, discussing the best position for the rooks, riding and stabbing the knight and playing tricks on pawns. He falls in love with the strength, virtue, and omnipotence of the queen. He desperately loves the only female figure in the most spectacular of games. He desires the queen, the majesty and the magic of this noble woman. A fundamental piece of the game, and of his life. But deep down he knows that, eventually, and not without pain, he will have to give her up. He will have to sacrifice the queen for much bigger gains.

He becomes embodied in the weakness of the king. This huge, masculine and ludicrous piece, which, when killed, represents the end of the game and of life. This dark figure, who always moves in fear and needs to be protected by everyone else on the board. The king—like his father, his homeland, his people—is extremely weak and limited. But Bobby must protect him at any price. He has a recurring dream: He never approaches the monarch, however much he wants to. He always looks at him with a distant gaze and, and if the king looks at him, he looks away. He knows that he must kill the enemy king, and that he must defend his own sovereign, despite the anger, hatred, and submission he feels for him.

He starts daydreaming about chess. His mother, concerned with Bobby’s obsession and alienation, takes him to a psychiatrist. The doctor, ignoring the grandiosity and importance of the game, comments: “There is a lot more to worry about in this world than chess. Don’t worry about it.” Huge mistake. There is nothing else in the world to worry about apart from chess.

His mother accepts the doctor’s advice, since she doesn’t have time for her son. She’s too busy working tirelessly for the family’s future. She deludes herself but already senses that their fate is doomed by this game.

At 8, Bobby takes on himself the responsibility of being the absolute best player. He announces his decision to the world: “I will be the newest and most brilliant world chess champion.” No one, except his mother, gives him any credit. He might be pretentious, arrogant, and stupid, but he is also a prodigy. A few years later, his prediction will come true, to the awe and amazement of the world.

At 13, he is already irremediably audacious, with a sharp technique and a bright mind. In a match against the master of the local club, he sacrifices the queen. The very woman whom he admires most and dreams so much of. The move he made was totally inconceivable. It shocked everyone. It caught even the master by surprise. At that moment, everyone thought it was a foolish mistake, but Bobby foresaw a checkmate 32 moves in advance. Everyone could see faults in his game, but Bobby promised a superhuman strike. Everyone expected an easy defeat, but Bobby won the game with exceptional expertise and prowess. The greatest chess player in the world was born and, eventually, he would end up sacrificing his own mother.

At that very moment the media turned their attention to the young man. Chess, until then, was a game scarcely ever watched or discussed. Only a few knew how to play it. The game was not a subject of admiration or curiosity for hardly anyone. There was a sense that it involved some kind of metaphysical mystery. Something that has always inhabited the collective unconscious. Indeed, the United States are masters at creating idols and then destroying them. And so, based on this unconscious enchantment of the popular imagination in relation to chess, and in possession of the most promising player of all time, the American sport industry decides to dedicate all its efforts and resources to building a perfect image for the game. Bobby emerges as a myth that instills devotion, he represents the geniality and superiority of the American people. He promises to confront the biggest enemy of the United States in a field where the adversary has always been the strongest and unbeatable player. He revisits the Cold War from a new perspective. He is ready to destroy his opponent. USA vs. USSR, now available in a chess game.

At 15, he becomes a celebrity. An icon. A star. He travels across the country showing off his talent in exhibition games. He plays against several opponents at the same time and destroys all of them in a matter of minutes. He gives talks at schools, clubs, on radio and television. Everywhere, he advertises the capitalist flag in a world shaken by the Cold War and the fear of communism.

Chess, a game always dominated by the Soviets, begins to fear the appearance of Bobby Fischer. What would happen if the Soviet Union was defeated? Would the United States become the new leading nation? Would democracy win? The American Dream saw in Bobby a great opportunity to defeat socialism. Of destroying the hegemony of the USSR in Eastern Europe through a messiah of capitalism, Bobby Fischer.

But Bobby still misses the presence of a father figure. It hurts him so bad that he can’t even talk about it. When asked about his father on television, he even cries. He knows nothing about him. He wishes he knew. If only he had someone to be inspired by. Someone to fly kites with, play football, basketball, chess. Someone to take him to the park, to run on the beach with him. But that someone does not exist.

Was it against his absent father figure that he rebelled years later? And could it be that by ditching, escaping, and cursing his own culture, he would be actually fighting the bitter projection of a father who abandoned him? Who forced him to constantly evade reality? Is this the father he will eventually see as the American state? The nation? The culture of his own people whom he now rejects and condemns?

“Chess is my alter ego. For me, there is nothing more rewarding in the world.” At 18, he is the greatest player of all time in the United States. The most talented figure in the world of chess. A living legend.

Despite understanding increasingly more about the imaginative power of those 64 squares, Bobby becomes even less acquainted with reality. He has no friends, he doesn’t relate affectionately to anyone, and he doesn’t enjoy life in any other way. All he wants is to improve and perfect his art. He decides to be the world champion, even though he doesn’t really know what that means. Chess is his only muse, his only companion, and his only comfort. He stops all contact with his mother. He becomes ashamed of her. He doesn’t want to be as weak and oppressed as she always was.

From 1957 to 1967, Bobby wins eight American championships. He is by now the mastermind of the game. An authority. A massive star. And so, he begins to live like the superstar he has created.

He was determined to gain the world championship at any price. This became his only reason for living. He knew he would have a long road ahead. First, he would have to win a tournament with 64 other players, a job he achieved in no time. Then, he would have to beat three grandmasters before he got to play against the world champion. These revered experts topped the world ranking list and were most likely the only players with whom he could compete on equal terms. Despite the instabilities that tormented Bobby’s life as well as his soul, he kept extremely focused, and he was looking forward to facing them. In order to achieve his dream, he would have to annihilate these players one by one.

The games were broadcast live as major events. Bobby Fischer, the most brilliant American mind, a nation’s pride, the glory of capitalism, confronting the world’s best players. This prodigious child, this national treasure, now defying the completely decaying socialist world.

And the first confrontation begins. It would be played in a best-of-11-games format. A victory would mark one point, and a tie would mark half a point. The eyes of the world watch the game between Bobby and the Russian Mark Taimanov, a man who had been champion of the USSR twice and one of the few players to beat six world title holders. This was someone who could end Bobby’s invincibility. Someone who could destroy the American dream while simultaneously testifying to Soviet supremacy. But none of this happens, Bobby decimates Taimanov 6 to 0. An extraordinary score, unthinkable, completely inconceivable considering the level of these players.

The Soviet government, shocked with this embarrassment, demands an explanation from Taimanov. He had been humiliated by an American, shaming the Soviet government and their politics. He had let the nation down, and as a punishment, he would no longer receive a salary and would be prevented from traveling abroad for the rest of his life. A complete disgrace, one that Taimanov should not be blamed for. He did his best, but Bobby Fischer did infinitely better.

In the second confrontation, Bobby Fischer faces the Danish contestant Bent Larsen. The only player to have faced and defeated the Soviets. A gold medalist at the Moscow Olympics, recognized for his creativity and audacity, this player, however, is no match for Fisher. He is defeated 6 to 0. The impossible is beginning to happen right in front the watchful eyes of the world. Fisher does not lose a single game, an extraordinary achievement, far beyond the realms of human possibility. Bobby Fisher now inhabits this superhuman place.

In the third game, he faces Tigran Petrosian, another Russian, known as Iron Tigran because of his solid, indestructible defense. He is a former world champion, feared and revered by many. Now the games start to become more disputed, and the Russian manages to win two and a half points. Petrosian tries to block Bobby’s destructive drive, but the American overcomes him mentally. Throughout the many moves of the game, Bobby shows incredible determination, outstanding concentration and a strength never seen before by any Soviet player. Bobby is there to annihilate his opponent in every way. He wins, and his victory destroys Petrosian’s career. Now, he is ready to face the defending world champion.

Awaiting him now is the great Boris Spassky, another Russian player who glorifies the Soviet’s superiority in this sport. Perhaps he is the one who could defeat the American, he has a huge arsenal of moves and a mental strength far superior to that of all of the other players. Bobby sees him as an enemy. One who is in possession of what should rightfully be his and is preventing him from taking it. He has to be destroyed.

Bobby knows that he still needs something else to be able to defeat Spassky. It’s not that he doesn’t have enough technical skill to win his game, but he needs to train his body to endure the stress of a series of games. And so, he dedicates himself to serious physical training, swimming, running, and stretching. He wants to be completely ready for the world title. His tormented mind is somehow in control, but his body needs to be strengthened. He doesn’t know it yet, but he is doing exactly what Max Nordau proposed years ago: the Muscular Jew. In August 1898, Nordau gave a speech at the second Basel Zionist congress in which he introduced the term Muskeljudentum—the controversial muscular Judaism—into the Zionist debate. Max Nordau would call for a program of Jewish-Zionist regeneration, trying to end the stereotyped belief in the fragility of the Jewish male body, always associated with Orthodox Judaism in Eastern Europe. For Nordau, these Orthodox Jews were considered weak and physically unprepared, the result of the long years dedicated only to the study of the Torah. Bobby, unknowingly, would no longer be one of them. He would show the world that he was courageous, strong, and fearless, in complete contrast to his upbringing and his origins. This new musculature and his highly focused mind would never allow his enemies to bring him down. He was ready, ready as he had never been before.

Finally, the series of matches for the world title begins in Iceland. Best out of 24 games. Spassky would have to score 12 points to keep the title, and Bobby would have to score half a point more than his adversary to be the champion.

He had always dreamed of that moment. He always imagined himself as a world champion. But now that he is so close to that dream, he cannot stop thinking about what it actually means. He doesn’t quite understand. What does it mean to be a world champion? What would he gain from that? Money? Fame? Women? He doesn’t care about any of those things. He just loves the game and wants to be the best. But what will happen after he becomes the best? What will his next challenge be? What will give new meaning to his life? He becomes frightened, he begins to panic, and he starts to lose control.

Now everything seems so real, and Bobby never liked reality. The reality that deprived him of his father’s love, a man he doesn’t even know. The reality that keeps him away from his mother and sister, and that made it impossible for him to experience love. All this just to become the world chess champion? What is chess? What is the real world? What is the purpose of life?

This is the start of Bobby’s ordeal. He begins to impose unrealistic demands in order to play a game. He is very scared, not of losing—that is something he never considered—but of the life that awaits him after the conquest of his dream. And so, the display of madness and hideous eccentricity begins. He demands a car, a helicopter, a tuxedo, a gold vibrator, gourmet food, private parties, dancers, orgies. He imagines meeting with the president, Elizabeth Taylor, getting a blowjob from Brigitte Bardot. He doesn’t even know what to ask anymore, and no one listens. He isn’t really interested in anything, except the game.

He doesn’t even show up to the international press conference. The ambassador, the president, Spassky, and thousands of viewers were present, and Bobby’s chair was empty. He had disappeared and no one knew if he would even play. In the United States, they even imagined that he wouldn’t go to Iceland, because he demanded more money, and the International Chess Committee did not allow it. However, an American millionaire who was a chess fanatic contacted Bobby and promised an even bigger prize to entice him to play. He was still not convinced. Money was not important.

He didn’t get his airline ticket until the last minute. He was seen running through the airport. And he disappeared before boarding. The aliens want to abduct me, they want to tear my mind apart, he thought as he fled. The audience fears the end of the show and the failure of America.

Bobby Fischer is very scared, not of losing—that is something he never considered—but of the life that awaits him after the conquest of his dream.

However, to everyone’s surprise he departs to Iceland, after all, and it seems that he will play. It was as if he was taming his monsters, at least for a moment. He manages to remove himself from the perverse world around him and get back to thinking exclusively about chess. He is reunited with his love and devotion for the game. He decides to face his opponent and destroy him.

The first game finally begins and is broadcast worldwide. Astonishingly, only Spassky is present. Bobby’s chair, empty again. The clock marking the Russian’s initial move is tapped on and Spassky moves the first piece, without his opponent’s presence. The world is silent, waiting for the outcome of this bizarre charade. Bobby is nowhere to be seen. No one knows where he is.

He begins making up stories. That the Soviet secret service is stopping him from competing for the world title. That he is being constantly stalked and watched. How can he concentrate with the constant fear of being murdered or poisoned? His madness becomes a political issue. Diplomat Kissinger is called in to mediate the conditions for him to play. If he wants protection, he will get it. If he wants more attention, he can have it. In a show of supremacy, the government states that they will do everything in their power to ensure everyone follows and supports Fisher. All he needs to do is show up and play.

Eventually, he presents himself for the game. He appears in the middle and starts to complain. He doesn’t like the lights, he can’t stand people so close to him and demands that the judge stay farther away. He is completely unfocused. He is afraid of winning. He is afraid that his dream will end. He is afraid of the future that awaits him.

In the first game he makes a stupid mistake. A move like he has never made before. Not even in the beginning when he didn’t know how to play chess did he make such a terrible move. The world is silent and Spassky wonders. Is this a trap? Is this an even more extraordinary move than the human intellect can ever conceive, or is Bobby becoming crazy? Nobody ever imagined that something so childish could happen at the level they were playing. Especially from the hands of a great master. But unfortunately, it was true. Bobby had finally made a mistake, losing the first game. The whole world questioned whether it was intentional and part of a bigger strategy. But everybody wondered if he had actually gone mad and lost the ability to play.

Bobby goes back home. Suffers. Cries. Hides. His thoughts are racing. He needs to win, he needs to be the world champion, but he is having a panic attack. His childhood ghosts haunt him. Voices and more voices disturb his mind. “You are rubbish, you can’t play chess. Hideous. Stupid.” The monsters do not stop, they will never silence. “You don’t even have a father. Your mother is a housekeeper.” In his dreams he is playing chess with his father, but his father has no face or body. He appears blurry, out of focus. When Bobby wakes up, he is scared, unable even to get out of bed.

Now the second game starts and again he is not there. He had demanded that the cameras were removed and that there should be no noise from the crew. Impossible. What he really wants is for the voices and screams from his nightmares to disappear. He has a fever. He gives up and runs away. He gets completely out of control. Spassky leads by two games to none. Bobby has never experienced such a disadvantage.

But reinvention is part of the life of geniuses and madmen. Bobby dreams of his mother, dressed as a red queen, but sweet, inviting him to dance in a house of mirrors. His monsters recede and he begins to concentrate again. “I love you, my queen.”

Once more he begins to feel the desire to play and to achieve his dream. He begins to focus. His controversial requests are surprisingly accepted and he starts to compete. This audacious, vigorous, and prodigious young man enters the great battle of his life with body and soul. Chess is a game he plays better than anyone else. His mind returns to focusing entirely on the game. Bobby is in ecstasy. Transcendental. Capable of anything.

And so, he wins the third game with a monumental victory, astonishing even Spassky. This is the first time he defeats a world champion. Now he is back in the game, more alive and healthier than ever. He begins to smile again, enthusiastically, destabilizing his opponent. His deliberate effort dismantles the Russian player. Finally, the long-awaited war in search of the title and the glory begins.

The Russians are shocked. The KGB accuses the CIA of sending electromagnetic waves that would have damaged Spassky’s concentration. The Russian champion feels weak, discouraged, and vulnerable. He alleges that his mind has been affected by infrared rays. This has never happened before. He accuses the CIA of poisoning his water and food, and disturbing his precious sleep. All of these charges are investigated by the Icelandic authorities and nothing is found. The truth is that the poison has only one name: Bobby Fischer.

The fight for victory continues. Spassky still manages to win some moves but is unable to stop the American. In a memorable game, Spassky even applauds his opponent. He knows that he will be crucified in the USSR. He knows that he will fall from grace. He knows that the government will condemn him forever. But there’s nothing he can do. He is in front an extraordinarily superior mind, one which has to be honored.

And Bobby, as predicted, wins the championship. At 29, he is the first and only American in history to become a world chess champion. He is finally recognized as the greatest player of all time.

His return to the United States becomes a huge spectacle. He is publicly welcomed as a hero, an international myth, an American living legend. He gives countless interviews and talks incessantly about his title and the superiority of the United States. He becomes a celebrity, worshiped and honored in every city he visits. Chess becomes the game of gods, and the greatest player in Olympus is an American. “Chess is the greatest of all games. It is the most magnificent sport for the human mind.”

Bobby makes a lot of money. He could have become a playboy, a womanizer, or a movie star, but he didn’t really care about any of that. He became a symbol of the success and supremacy of Western intellect, but the monsters in his mind never abandoned him.

Now he feels a disabling weakness. He has no desire to do anything. He needs to find a new path to follow, and he continues to panic despite having achieved his dreams. The monsters in his head reappear louder, stronger, more vigorous, and more hysterical. They yell and shout at him. They scare his reason away. They kill his desire for chess. He sees no point and no reason to devote himself to the game anymore. He also doesn’t see any point in continuing to live. He stops speaking to his mother. So far, they had already become distant, but they still had a cordial relationship. He believes that she underestimates his capabilities. That she makes him weak. She represents his inglorious past. He is lost.

On one of his sleepless nights, he hears an impassioned speech from a pastor on the radio. His eyes shine again. He feels seduced by the conspiratorial ideas of the Worldwide Church of God. “Follow my path, and in the end, you will find a truly peaceful world. UTOPIA: We will resurrect the Roman Empire, and we will reign again.” This madness suits him very well. Now he will dedicate himself to the church, in the same obsessive way that he dedicated himself to chess. He donates 20% of his world prize to the church and receives in return the home of a “future Roman king.” There, for three years, he assimilates the orthodox and prejudiced principles of the sect. He no longer gives any interviews, he doesn’t play chess anymore; all he does is to study the precepts and doctrines elaborated by his new guide and mentor: Herbert Armstrong.

But because he was the world chess champion, he is called upon to defend his title. There is a new, top-level opponent who has defeated all players and now claims the title. Bobby has to confront him if he wants to keep his position. The problem is, he is no longer interested in chess. He is only interested in his new religion, even though, in his heart, he cherishes the fact that he is the world chess champion.

And so, he becomes terrified again. Not of the possibility of losing, but of the possibility of facing real life. He makes 179 ridiculous demands in order to face the new opponent. To make sure that the matches would be held, the management decides to honor every single one, but still, Bobby refuses to play. And so, the world meets its new champion, Anatoly Karpov. The end of Bobby Fischer begins.

He becomes immersed in the cruel pragmatism of the church. He feverishly reads and scrutinizes all the apocryphal texts he encounters, and he believes in them, particularly in those that regard the Jews as a perverse, despicable, and deicidal race. His own people, whom he now hates, become for him the real culprits for the misery of the world. He sees them as part of a bigger plot to seize global power, taking refuge in the protection given by the American government. He focuses all his melancholy and gloom on hatred for the Jews and the American people. He hates his mother. In the middle of the night, he calls her name and curses her. He refuses to be part of her culture and rejects her blood heritage. Without realizing, but he begins a journey of self-destruction.

He falls apart once more when he discovers that the leader of the church, the “kind” pastor Armstrong, has been involved in crimes of extortion, sexual abuse, and corruption. After the tragedy in the Jim Jones community, the United States begins to persecute the leaders of all religious sects. Extremism begins to emerge, arousing great fear in America. Bobby no longer finds refuge in any community and becomes a hermit, full of sick ideas about the world.

Paranoia. Imagination. Schizophrenia. Bobby Fischer is seen wandering around with a suitcase full of pills, which he uses as antidotes against the world’s poison. He believes everybody is conspiring against him, his principles, and his convictions. He feels blamed for something he was never guilty of and feels the pain of a crime he did not commit.

On a given day in 1981, for luck or lack of it, Bobby is mistaken for a bank robber. He is arrested, tortured, and beaten. He becomes even more disgusted with America. He writes a pamphlet entitled “I Was Tortured in Pasadena Prison.” He believes he is being persecuted. “They told me they could have sent me to a mental institution for observation. I was asked what year it was, what month it was, etc. I easily answered all these stupid questions. ... ‘We are going to send you to a mental hospital. You are obviously mentally deranged.’” Now he needs to run away from the Jews, from the Americans, from the Soviets, and from himself.

He is haunted by the ghosts in his head. He disappears. Rumors arise about his whereabouts, but no one knows for sure where he is. The voices now shouting in his mind say there is a plot against him, and that he must protect himself from everyone.

The Protocol of the Elders of Zion falls in his hands, and he is convinced that the America that welcomed him, and which now destroys him, is entirely Jewish. He will not be a member of this disgraced race. He begins to entertain the idea that he is no longer a Jew. He, who has not spoken to his mother in years, and has never had a relationship with his father, convinces his monsters that there is not one drop of Jewish blood in his body. Now he must fight against this fossilized race, a race that deserves to be extinct but insists on living like parasites. He buys all the neo-Nazi literature he can find and becomes an expert on anti-Semitism. He confronts his country and his culture, cultivating a deep hatred for Jewish America.

One day a Hungarian young lady appears and suddenly changes Bobby’s trajectory. She was an ardent fan, passionate about him, his technique, his masterly moves, and his inexhaustible creativity. She fell in love with his art but ended up transferring that love to the artist. And so, she decides to write a letter to him, inviting him to play again.

She is 16 years old and considers him to be the Mozart of chess. “Why are you so reclusive? You are the greatest chess player ever, the ultimate mastermind. You are an Einstein. A da Vinci. You must come back and play again.” When Bobby read the letter and saw the picture of the sender, he instantly remembered a youth tournament earlier in his career, one which he did not win. He lost that tournament due to lack of concentration, distracted by something he considered to be more important than chess.

Back then, an ex-friend, also a chess player, had introduced him to an attractive woman with whom he fell in love. This was the first time Bobby encountered the true beauty of a female body. One night, just before his worst performance in any championship, he would experience the texture, the form, and the scent of a woman’s body. No, the world wasn’t just about chess. Bobby, who was obsessed with the possibility of discovering brilliant openings, of conquering the territory of the enemy, fixing a position in the center of the board, or preparing a sublime attack, realized that life is much better with the scent of a beautiful woman. Seeing that naked body sprawled across his bed would change Bobby’s perspective in life from there on. No more thinking about his opponent’s next seven moves and possible variations. No more memorizing all the games ever played in the world. No. Never again. All he needed was to savor those amazing breasts, sublimely laying there, just within reach of his mouth. All he wanted was to become inebriated by the sap and bitter taste of that breathtaking forest close to his lips. For him, in that instant, it was enough to live the ecstasy of smells, odors and fragrances of that woman’s extraordinary sex. And so, he plunged with his entire soul into an inconceivable sea of senses and lived an intense climax with his true queen.

The next day he was incapable of seeing any beauty at all in bishops, horses, or towers. He was unable to focus his attention on his opponent’s mind. He just wanted to luxuriate in that intoxicating taste again. That sweet aroma that was still in his mouth. He needed to feel the texture between a woman’s legs again, and the painful and delightful pulse of his penis. But sadly, that was all over. The woman had rejected him and began to feel repulsed by his underdeveloped and frail body. To his disgrace, he once again took refuge in chess.

But when he received the letter from the Hungarian girl, it reminded him of the experience with that woman and he thought about the possibility of falling in love again. He writes to his mother and tells her that he is in love. And so, to please his new lover, he agrees to play again. He makes plans to marry her and have a family.

His return to the board is controversial. He was supposed to play a game in Yugoslavia against his old opponent Spassky. But at that time, Americans were banned from entering the country because of a civil war. Bobby makes a public display of his hatred for the West, for the Jews, and for the American flag. In an angry interview, he completely defies the United States, and leaves for that forbidden country.

The United States warns him that if he does play, he will receive a fine of $250,000, as well as a 10-year prison sentence. He displays this official statement in public and spits on it. He insists on playing and receives more than $3 million for the game. He defeats Spassky again, and in a mediocre, outdated, and depressing game he demonstrates the degradation of a brilliant mind. He departs for Hungary in search of his love.

But in Hungary, when the girl meets him in reality, she doesn’t like him. She is not seduced, not even for one moment, by that bitter, bearded, and self-hating man who turned up at her house. With aversion and disgust, she decides to get rid of him.

Bobby is at the bottom of the heap. Without any purpose in life. He has money, but he has neither a home nor affection. He now resents even more the country that is bothering him. He, who was the ex-idol of a generation, is now despised by everybody, including himself. He hates himself, and he hates the world that produced him. For 12 years, he wanders around the world, homeless. He goes to live in Japan, the Philippines, and Iceland, but never returns to himself again.

His mother dies in 1997. His world falls apart. He lost the one love of his life, his queen, and only now does he realize it. He needs to say his last goodbye, but he cannot attend the funeral, as he is prevented from entering the United States. He suffers a lot, and his hatred for the United States becomes even more profound. By that time, he had become closer to his mother. They spoke quite frequently on the phone. He was searching for maternal affection to escape the pain and rejection caused by Zeta, the Hungarian girl who made him come back weaker, with increased repulsion toward himself.

He focuses all his anger on the Jewish people. “These filthy bastards. You know that they have been trying to take over the world. You know they invented the story of the Holocaust. Such a thing never existed. There was no Holocaust for Jews in World War II. They’ve been inventing this persecution rubbish since time immemorial. They are liars and disgusting people. That’s all they will ever be. That is the Jewish mentality. They are all criminals. They torture their prisoners in the worst possible way. It is illegal! They don’t even deny that they practice these tortures. Jews are the bastards of history. They are miserly, the worst crap on the face of the planet. Who else mutilates their own children?” Bobby is destroying himself, blaming himself, annihilating himself, but he doesn’t realize. He is getting older and becoming more sick and more depressed by the hour.

But 2001 is the year of his glory. Of his joy. Of his respite. The collapse of the Twin Towers would edify even more his wrath. A confirmation of his curse.

He would continue to publish hostile articles against the United States and the Jews. His anger never subsided, and he never found peace. He regrets the end of his glorious past and longs for the life he had before. His health is completely deteriorating, and his anger does not go away.

He is alone in his bedroom when he feels that his time has come. He manages to call an ambulance. In the time before he loses consciousness, he never smiles. His anger is intense, and he is sure that he is dying at the hands of his executioners. Even so, he has time to reflect on his life. Bobby remembers his love for chess, that almost sickening desire that life could just be a beautiful mirror image of a chessboard. And he imagines himself as the king, admired, protected, and enchanted by all of his subjects and friends. He takes a deep breath and becomes full of a melancholic longing. He thinks of his mother, and of an affectionate cuddle he received when he was still a child. Perhaps that had been the only one. When he won his first championship, his mother, to his surprise, gave him a kiss and a hug in front of everybody. He had forgotten all about that moment, but now he knows that the reason why he had dedicated so much of his life to chess was precisely that. But his dedication also separated him from his mother. He became too obsessed, too neurotic, and too lost in his search for perfection. The perfection of that tender moment he never experienced again. All that transformed itself in anger and bottomless perdition. Bobby hated himself throughout the path that life took him on. He detested his body, his mind, his ideas. And he hated the other, the stranger, the one who always played with his feelings. He realizes that his moments of pain were much greater than the ones of love. The death that is now approaching seems to him the best option. He surrenders and finally finds relief.

He died vilified and almost completely forgotten in 2008. Many still imagined that he would reappear claiming the world title. Many dreamed of his sublime return, repudiating his hateful ideas and dedicating himself only to his art.

But unfortunately, he never came back. Perhaps he is playing a divine, or hellish game of chess with other madmen, or geniuses and terrorists of mankind. The world is grateful to him for the magnificence with which he treated the most perfect of games, but he will be forever blamed for his infamy as a human being.

Translated from the Portuguese by Elton Uliana. Originally from Meshugá: um romance sobre a loucura (Meshuga: A Novel About Madness), by Jacques Fux, from José Olimpo publishers, Rio de Janeiro, 2016.

Jacques Fux is a Brazilian writer and professor. His books have been translated into Hebrew (Antiterapiot, Carmel), Spanish (Antiterapias, Textofilia), and Italian (Sulla Follia Ebraica, Giuntina).