Jan Kott Would Have Loved ‘Waiting for Godot’ in Yiddish. No, He Didn’t Speak Yiddish.

I was reminded of the Polish critic and Shakespeare scholar at the New Yiddish Rep’s production of Beckett’s masterpiece

“Wherrrre is the place of the audience wat-ching the play?” I thought of this question—originally asked by Polish theater critic, essayist, teacher, translator, editor, dramaturge, and director Jan Kott—when I went to see New Yiddish Rep’s short-run production of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot. Kott would have felt at home at the Castillo, with the aged theater people in the front rows—the men in turtlenecks and over-sized jackets and the women with henna-colored hair—engaging in shop talk, waiting to hear a language, as he once put it, “close and distant … at the same time.”

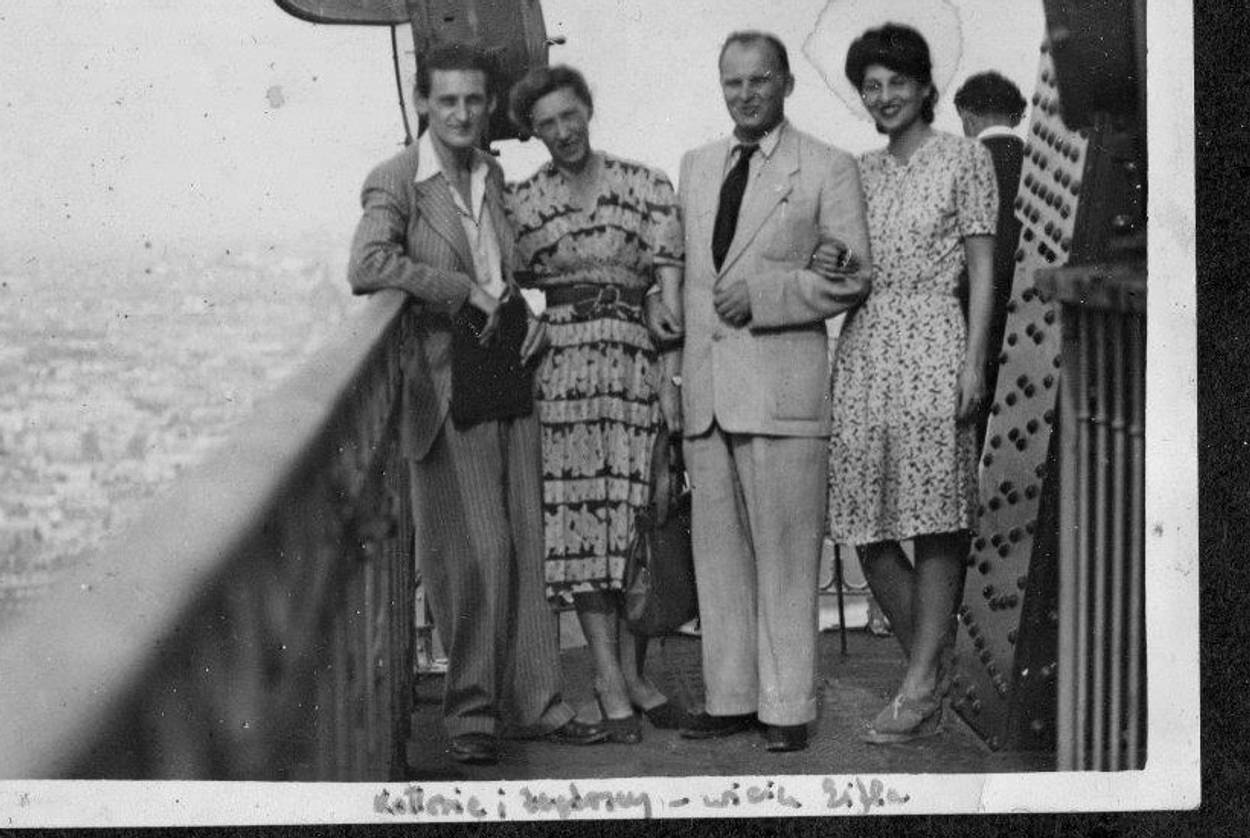

Kott came to the United States in 1966, teaching first at Yale and then at Berkeley before receiving a permanent appointment at Stony Brook. I got to know him in the early 1980s when I edited his essays for a magazine that was published in Chicago. David Levine caricatured him for the New York Review of Books with extravagant elf ears and a gallantly mischievous grin, which he flashed at women with sexy legs. (As his son Michael told me, he did this even after he himself could no longer walk.) Kott was known for some shenanigans but also for his brilliant and associative mind. He made daring, leaping conceptual connections and was fascinated by the seduction of imagination and intellect by politics, violence, and sex. He called this the “serpent’s sting,” and he had his first adventure with it in 1934 when he was a teenager, demonstrating in the Warsaw Jewish quarter with the Polish Democratic Youth who were commemorating, as Kott put it, “the three L’s: Luxemburg. Liebknecht, and Lenin.” Afterward, he spent a week in the Danilowiczowska Prison with the prewar communists. His first academic project (never completed, since the manuscript perished during the war) was a study of Apollinaire as the editor of the Marquis de Sade.

In English, Kott dragged his words behind his thoughts, rolling r’s in raspy phrasing: “An ém-i-grrrré is a man who has lost ev-errr-y-thing ex-cept his ac-cent. You have herrrre a verrrr-y good ex-amp-le of an ém-i-grrrré.” Best known for his book Shakespeare Our Contemporary, Kott was at the center of postwar avant-garde theater, and the world of Beckett was seminal for him. He reviewed the first Paris production of Waiting for Godot for the Polish press, inspiring a Polish translation and Warsaw production in 1957. His interpretation of King Lear, seen through the prism of Beckett’s Endgame and staged by Peter Brook, transformed modern theater.

What would he have thought of the New Yiddish Rep’s production? I think his response would have been a complicated and fascinating one. Kott, who was born in 1914, came from a Polonized Jewish family. Hilary Nussbaum, his great-great grandfather, had translated the Pentateuch into Polish. Kott was baptized as a boy, and more than once he told me that being uncircumcised saved his life. He didn’t speak Yiddish, but he attended Yiddish theater especially to see the great performances of Ida Kamińska, whom he had known since childhood when she lived in the same Warsaw apartment house as his grandmother. Watching Kamińska’s performance of Mother Courage in 1957 in an almost empty Warsaw theater, Kott wrote about her tragic role as a metaphor for the death of the Warsaw Yiddish stage. For Kamińska, there was no choice but to go on, as Kott put it, “against the logic of the world.”

At the Castillo Theatre, a large portion of the New Yiddish Rep’s audience had a connection to the text of Godot and to one another. In Kott’s terms, their remembered time was the same as the time of the actors, which created a great feeling of empathy and comfort in the theater. As a friend said to me, “It was like wearing an old coat.” A less-sophisticated segment of the audience experienced the production—the simplicity of the stage, the derby hats, the insults—Se shtinkt!—as physical comedy, something out of Buster Keaton. It was disconcerting to hear laughter in the dark places, even though the the mixture of high and low is there in the text.

A lot has been written about the task of presenting the annihilated Yiddish language on the contemporary stage (the NYR production provided supertitles in English and Russian), but I think Kott would have been astonished by the transformative and compassionate interpretation of Moshe Yassur and his cast. The emotive quality of Yiddish—and NYR’s production included both the literary, Litvish dialect a well as Warsaw Yiddish—seeped into the characters, creating a three-dimensionality that’s unusual in productions of Beckett. The Yiddish language converts Gogo, Didi, Lucky, and Pozzo into Jews. Beckett’s skepticism becomes Jewish skepticism. Lucky’s tirade, chanted in cadences of prayer service supplication, becomes Jewish despair and goes a long way toward contextualizing his preposterous job as Pozzo’s mule. I know he didn’t mean to say it out loud, but the man sitting behind me couldn’t help himself, “It’s the Holocaust,” he whispered—and I didn’t mind the intrusion.

By translating the poetic text into Yiddish, NYR intended to pay homage to Beckett’s work in the French resistance where waiting had the distinct meaning of awaiting a connection that might or might not materialize because of betrayal, sabotage, bad luck, or human error. During the first European performances of Godot, the theaters were filled with people who understood the danger, boredom, anxiety, absurdity, meaningfulness, and meaninglessness involved in such waiting. The actors, the characters, and audience mirrored one another; almost everyone had suffered and been compromised. During the war, Beckett had been working as an underground courier in Paris when someone informed on his cell. In Poland, Kott was shelled and taken prisoner by the Soviets, placed on a deportation train and released, and transported to Majdanek by the Nazis. He was court-martialed by partisans and sentenced to be shot, afflicted with malaria, typhus, and diphtheria, had a spot on his lung, was sentenced to be hanged, belonged to the Communist Party in postwar Poland, and then resigned.

The first time I met Kott, he was seated behind the branch of a potted palm in the dark lobby of a west-side hotel. He had situated himself carefully, and I remember thinking, “Here’s a man who’s come to an appointment with expertise; he knows how to blend in, size one up, or disappear if necessary.” When you were with Kott (who died in 2001), the stories spilled out in his mangled English, playing back and forth outside of time or, more precisely, in Beckett’s time. In some productions of Godot, the simultaneity of Beckett’s time can be exhausting, but in the NYR production, the intermingling of present, past, and future had a clear logic. The Yiddish Godot was less abstract and more real. One of the gifts of this production is that it’s helped me understand what Kott meant when he said, “We do [Brecht] when we want Fantasy. When we want Realism, we do Waiting for Godot.”

Waiting for Godot from Castillo Theatre on Vimeo.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Frances Brent’s most recent book is The Lost Cellos of Lev Aronson.

Frances Brent’s most recent book is The Lost Cellos of Lev Aronson.