A Holocaust Fairy Tale From France

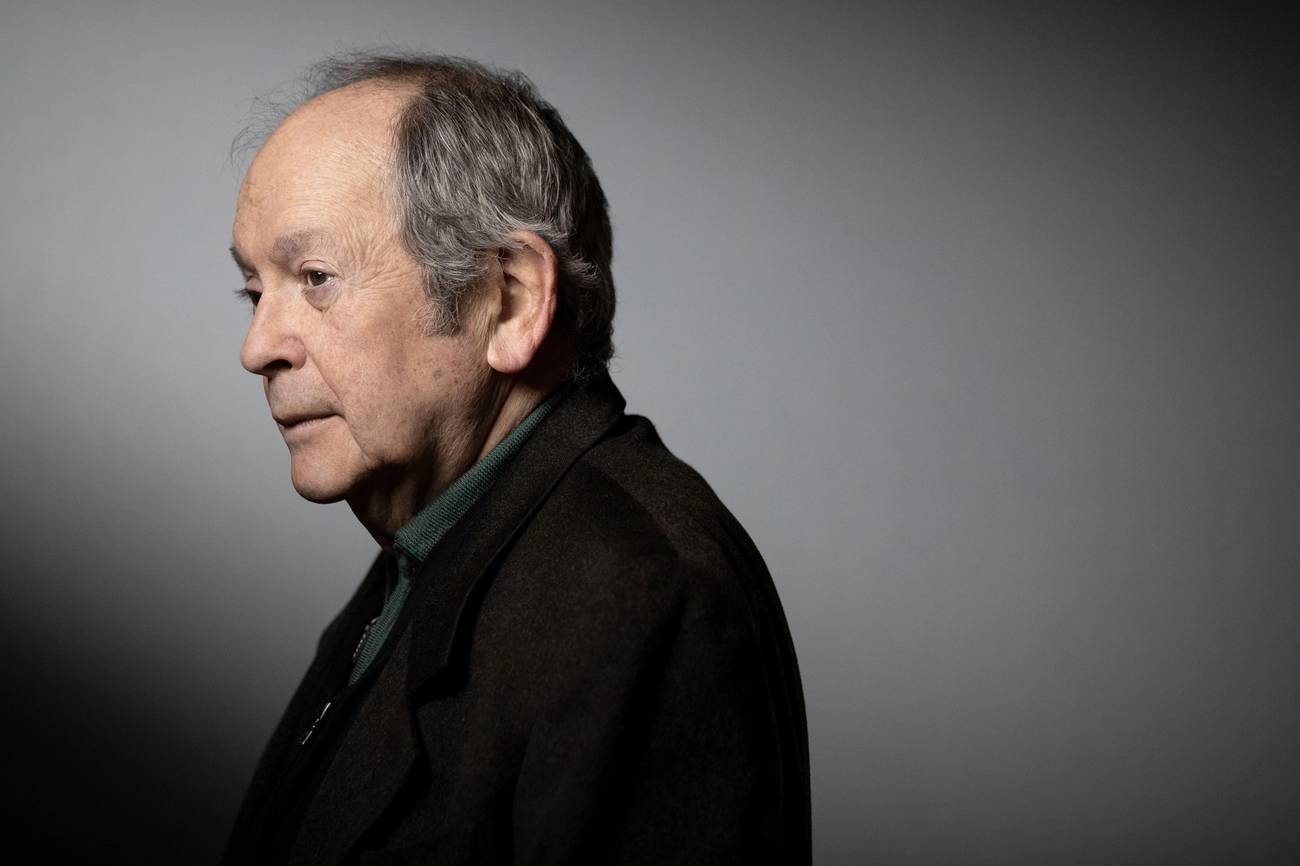

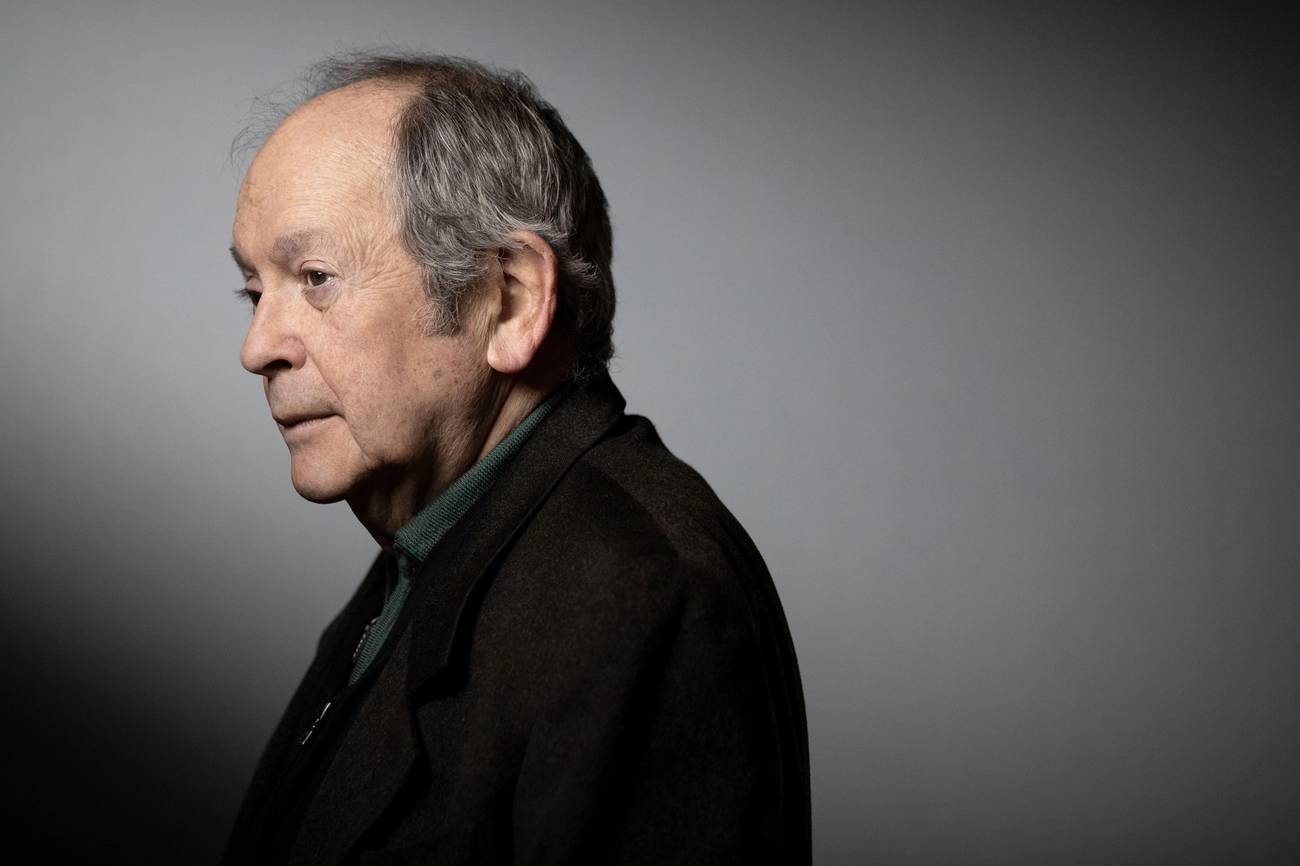

Jean-Claude Grumberg finds the unbelievable truth in ‘The Most Precious of Cargoes’

In Hop o’ My Thumb, a fairy tale published by Charles Perrault in 1697, a poor woodsman abandons his seven sons in a great forest. The youngest, smallest, and pluckiest of the boys outwits an ogre and saves the children.

The Most Precious of Cargoes also begins with a poor woodsman in a great forest, but its narrator immediately assures the reader: “No, no, no, fear not, this isn’t Hop o’ My Thumb. Far from it. Like you, I hate that mawkish fairy tale.” However, this story begins with the familiar incantation “Once upon a time” and later affirms: “this is indeed a fairy tale.” Jean-Claude Grumberg’s utterly disarming and distressing novella entices with the simple syntax and innocent vocabulary of a fable for children. But he doth protest too much. Grumberg’s repeated insistence that the painfully crushing plot is just a fiction merely emphasizes how the barbarity he evokes was all too real.

The year is 1943, and a cattle car is carrying its human freight from Drancy, the internment camp outside Paris, to “the pit of hell.” Crammed on board are a father, a mother, and their infant twins, male and female. During a brief stop in the forest, the father resolves to save at least one of his children from certain death. Making a kind of Sophie’s choice, he has barely enough time to push his baby daughter—swaddled in a fringed prayer shawl embroidered with gold and silver thread—through a slat and out into the open air. The train barrels on to its sinister destination, where, after failing an immediate selection process, the mother and their infant son vanish “into the thin air or the boundless depths of the desolate Polish sky.” The father, a medical student, is spared to labor as a barber, shearing the hair of new arrivals.

Meanwhile, a poor woodsman’s wife who longed for a child finds the abandoned Jewish baby by the side of the tracks and determines to adopt her. Repulsed by what he calls this “misbegotten abortion of a Christ-killer,” her husband aims to turn the tot over to the authorities. He argues that the kind of people who would throw their baby from a train are “heartless” and that the child must surely inherit her people’s heartlessness. Besides, saving a Jew could get them killed. “Don’t you know,” the woodsman asks, “that to shelter the heartless is forbidden on pain of death? They are the ones who killed God.” However, his wife is adamant about keeping the baby. Eventually, the husband warms to the young addition to his family. Despite the danger from “hunters of the heartless” (i.e., anti-Semites), they provide a safe and loving haven for the beautiful young girl.

Few of the plays and children’s books that have established Grumberg’s eminence in his native France are available in English, but François Truffaut’s 1980 film The Last Metro, on whose screenplay Grumberg collaborated, is certainly known in the United States. Though he is a Holocaust survivor, both his grandfather and his father, who were rounded up and killed in Auschwitz, were not. A precious cargo himself, like the baby adopted by the woodsman’s wife, young Grumberg got through the war precariously, sheltered by courageous families in the town of Moissac, in southern France. An appendix to The Most Precious of Cargoes—reporting that only two of 778 in the convoy that took his grandfather to Auschwitz and only six of 1,000 in his father’s convoy made it back alive—makes explicit the author’s personal connection to his “fairy tale.” Of the 330,000 Jews in France in 1940, 75,721 were deported to a camp. Only 2,654 returned.

Grumberg grapples with the enormity of the Shoah through the principle of synecdoche—a part standing for the whole. Paring away superfluous verbiage and nonessential details, his spare prose, trenchantly translated by Frank Wynne, bears the weight of Six Million. Though Grumberg calls the father who saves his infant daughter by abandoning her by the tracks in the forest “our hero,” he never names him, as if individuation would diminish the general devastation. To appreciate the anonymous man’s heroism, and the generosity of a strange benefactor, it is necessary to reach the heartrending conclusion of a story meant to be read in a single bated breath.

The work’s epilogue teases the reader’s credulity. “You want to know if this is a true story? A true story?” Grumberg asks. His answer, “Of course not, absolutely not,” reaffirms his claim that it is all a fairy tale. But then he proceeds to support that claim through a long series of disavowals that only the most obdurate and malicious of Holocaust deniers could support: “There were no cargo trains crossing war-torn continents to deliver urgently their oh-so-perishable cargo. No reunification camps, internment camps, concentration camps, or even extermination camps. No families were vaporized in smoke after their final journey. No hair was shorn, gathered, packaged, and shipped. There were no flames, no ashes, no tears. …” Since we know that these genocidal horrors did occur, that—hard as it is to believe—there were in fact cargo trains that transported human beings to extermination camps, we are forced to read Grumberg’s indelible “fairy tale” as accurate history.

For all his cunning irony, Grumberg is probably sincere about his distaste for “mawkish” fairy tales. His own fairy tale, a story of villainy and valor, loathing and love, earns a reader’s fears and tears without being sentimental. The standard disclaimer on the copyright page—“This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously and are not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, organizations, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental”—is a blatant lie in the service of truth.

Steven G. Kellman is the author of Redemption: The Life of Henry Roth and Nimble Tongues: Studies in Literary Translingualism.