Sports Book King Jeff Pearlman Dishes on the Lakers, Wishes He Had an Afro

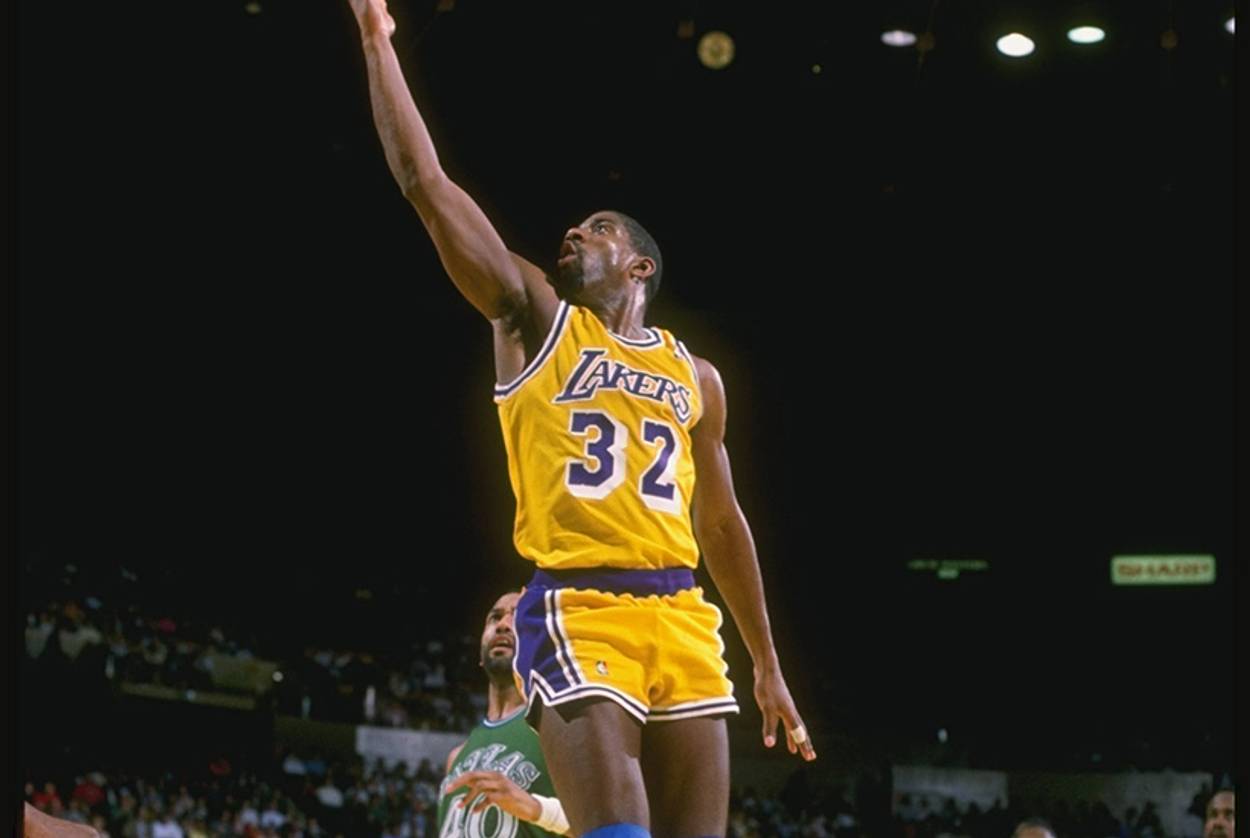

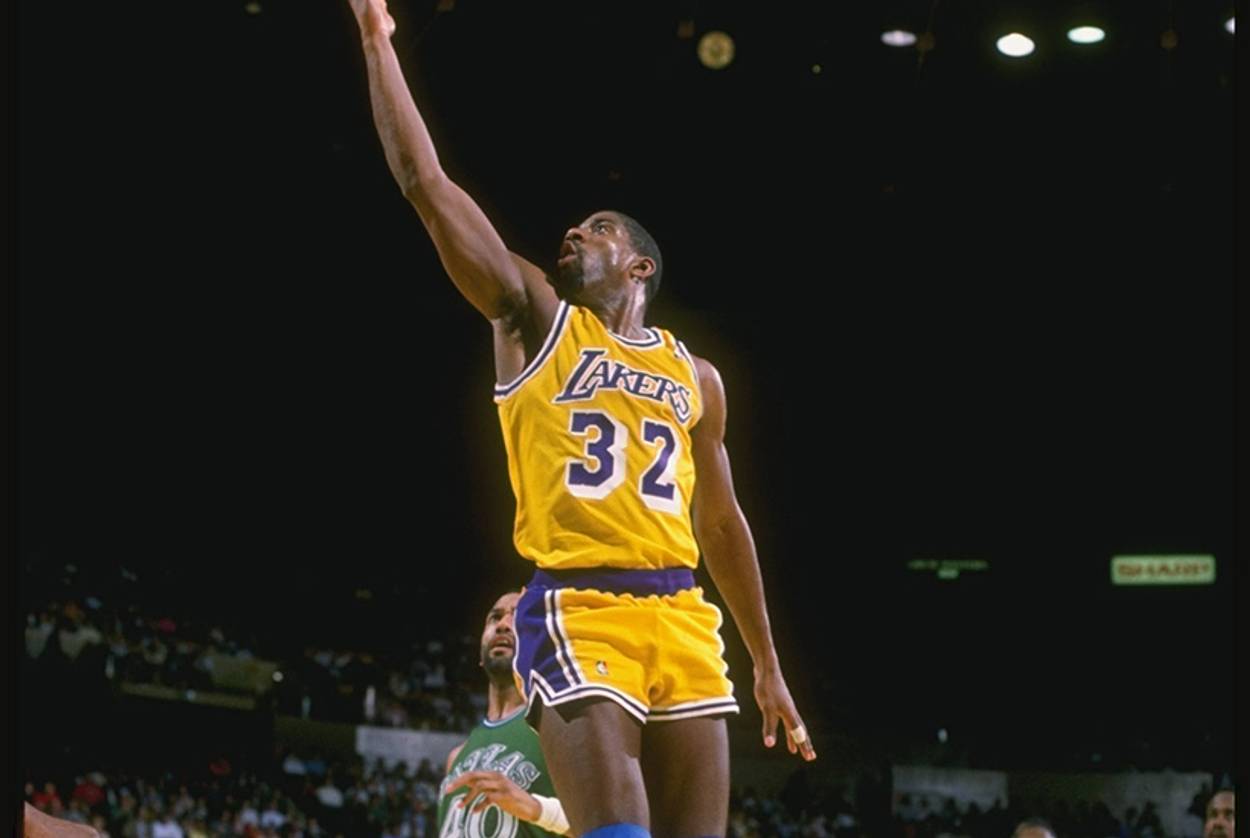

As the NBA playoffs begin, a new book revives the big stars, drugs, sex, and rivalries of Magic Johnson’s 1980s basketball dynasty

When Jeff Pearlman was a boy in the upstate New York town of Mahopac, he used to field phone calls from the local librarian—a woman named Gerry. Pearlman was a regular at the library, enthusiastically checking out all the newest sports biographies. He would bring home the latest book on Bo Jackson, or Ron Guidry, or Rod Carew, sit on his bed, and plow through them. After a while, the librarian noticed his voracious hunger for sports books, and started holding new arrivals for him behind the counter. “I would get calls at my house: ‘We have the new Warren Cromartie book about playing in Japan’ ”—the delightfully obscure Slugging It Out in Japan: An American Major Leaguer in the Tokyo Outfield. “ ‘I’m going to hold it for you.’ It was a mile-and-a-half walk from my house. [I’d] run to the library, get the books, go home, read through them.”

A sports-besotted Jewish boy in an overwhelmingly white town in Putnam County found himself fascinated by the glimpses it offered of another world. “As a kid, I frickin’ loved Afros, and I wanted a cool name,” said Pearlman, now 41. “I wanted to be a baseball player with a toothpick in his mouth like [longtime Kansas City Royals shortstop] U.L. Washington.” Pearlman’s parents considered Sports Illustrated too expensive, so they bought him a subscription to the now-defunct Sport magazine, which he regularly devoured. One day, his neighbor left a handful of cardboard boxes crammed full of back issues of Sports Illustrated by the curb for the garbage collectors, and Pearlman snuck over and smuggled them into his house like contraband. Visits to his friend Dennis Gargano’s house offered a chance to talk to Dennis’ dad Vinny, a former Dodger fanatic who had embraced the Mets as a substitute passion. “I was in love,” Pearlman writes in the prologue to his book about the 1986 Mets, The Bad Guys Won!, “and even though Teresa McClure, my schoolboy crush, habitually ignored me, the Mets never let me down.”

Pearlman is now a well-regarded sportswriter, former Sports Illustrated contributor, and biographer, with a terrifically enjoyable new book about the 1980s Lakers dynasty, Showtime, but his reading life today is not all that different from that of his childhood. Once Pearlman has settled on a new topic for a book—previous works have tackled the 1986 New York Mets, the Dallas Cowboys Super Bowl teams of the 1990s, disgraced baseball stars Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens, as well as NFL great Walter Payton—he heads to the library to research his topic.

Frequenting the Sports Illustrated library and the Los Angeles Public Library for Showtime, Pearlman uncovered every article, every interview, and every transcript on the Lakers of the 1980s that he could find, accumulating a file thousands of pages thick. He then got his hands on every book written about the Lakers and the NBA of the 1980s and dutifully made his way through them, too. “My wife is always reading these books that bring her joy, and I’m reading Michael Cooper’s autobiography from 1982,” he joked. “You become obsessed beyond obsessed with the subject.”

Pearlman did not always understand the process of writing a sports book with the same precision. Jack McCallum, a colleague and quasi-mentor at Sports Illustrated, remembers getting a call from Pearlman, then a novice journalist, after McCallum had co-written Shaquille O’Neal’s autobiography. Pearlman wanted to know how much of the book McCallum had written, and how much O’Neal had contributed. “And I laughingly told him, ‘Come on, man, I wrote everything!’ ” remembered McCallum. “We always had a joke about that afterwards, when he started writing books.” Pearlman soon joined McCallum at Sports Illustrated, where he made a name for himself covering baseball for the magazine.

Selling a book like Showtime is an effort in guesswork and pretense. The library work provided the rough outline of the material, but the real effort came later, after the book was sold, when Pearlman began the arduous task of locating and interviewing former Laker players, executives, coaches, staff, spouses, and opponents. “You don’t know who you’re going to track down, you don’t know what stories will be told, and you certainly don’t want to write a predictable book that reads like every other book that’s ever been written about the Lakers, or comes straight off of newspaper clips,” Pearlman said. There was an inherent challenge to writing a book about these Lakers as well, one McCallum warned him of: their reputation as being “difficult to deal with.” “A lot of the guys turned into closed doors,” McCallum said. “Kareem [Abdul-Jabbar] was one, James Worthy was one, Pat Riley changed. Byron Scott never said much. In terms of being able to tap into the main characters, I told him it was going to be a challenge.”

Each book tends to take Pearlman about two years from start to finish, with a year and a half devoted to research and interviews and the last six months devoted to writing. As would be expected, a good portion of Showtime is dedicated to the larger-than-life icons of the Lakers’ five-title run: veteran center Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, who made a habit of dissing fans and ignoring journalists; longtime Head Coach Pat Riley, whose burgeoning self-regard turned him from a highly effective steward of the Lakers’ impressive assembly of talents to a me-first egomaniac; and of course Magic Johnson, the 6-foot-9 point guard whose flair helped revitalize professional basketball after its drug-addled seventies nadir. (All three have led productive, engaged, and diverse public lives since retiring as players.)

The Lakers played a glamorous, energetic style of basketball crafted, as Pearlman takes pains to note, by their Coach Jack McKinney, his time with the Lakers cut short by a traumatic bicycle accident. “When you had Magic pushing the ball, and Byron [Scott] in the right lane and James [Worthy] in the left lane, running, and Kurt [Rambis] rebounding, well, it was as good as it could get. Basketball paradise,” longtime Assistant Coach Bill Bertka told Pearlman.

The team’s mystique was as much about the go-go 1980s as the basketball itself.“Showtime was loud music, big breasts, screaming adoration, fans dressed in their absolute best,” writes Pearlman, and Showtime turns much of its attention to matters off the court. Pearlman chose not to write a book overly devoted to Johnson’s sexual exploits, but the permissive lifestyle of NBA players crept in, regardless.

Like: How could anyone write a book about the Lakers without making mention of the Forum Club? The private club inside the arena where Lakers could indulge their vices away from the prying eyes of fans and the media was so alluring that opposing players often rooted for games to end so they could enter its sanctum. Even the notoriously standoffish Abdul-Jabbar was said to have had recurring dalliances at the Forum Club after games.

Pearlman’s previous sports-team books—The Bad Guys Won!, about the ’86 Mets, and Boys Will Be Boys, about the ’90s Cowboys—were breathless accounts of wildly successful teams that struggled with out-of-control egos, misbehavior, and intra-team dissent. Pearlman sees Showtime as distinct from its predecessors, but the template—of big stars, drugs, sex, and intra-team rivalries—remains much the same. These Lakers, like those Mets and Cowboys, were not just champions but idealized representatives of a place and time: The Lakers were symbols not only of glitzy L.A. but of the excess that pervaded the era.

Showtime is also a book about the racial politics of the NBA of the 1970s and 1980s: the racist antics of fans, the mostly white owners’ sense of superiority over their African-American players, the ever-present white bench players. “There was this mentality among owners that it can be a black team, but it can’t be too black,” said Pearlman. “You have to have some white element on the team.”

Pearlman was as excited about talking to the lesser names on the team, who often offer better, fresher material. You start interviewing guys like Johnson and Riley, and “they don’t actually remember events anymore, they remember what they’ve told about the events,” Pearlman said. “You start getting carbon copies of what they’ve said in their books and in a million interviews.” So, he spent a day with former Lakers reserve Wes Matthews at a diner in Bridgeport, Conn. “I would take a diner lunch with Wes Matthews over a diner lunch with Magic Johnson,” he said. “My philosophy is, he has not told these stories to anyone for 30 years, and Magic Johnson has told these stories repeatedly for 30 years. Do you want the fresh memories of the era, or do you want the recycled memories of the era? I want the fresh memories.”

Pearlman is mining in search of what he calls “nuggets”—lesser-known tidbits of information, or forgotten stories that illuminate the character of his subjects. (One of my favorites is his casually mentioning, in The Bad Guys Won!, that Mets third-base coach Bud Harrelson went home and impregnated his wife after a particularly memorable game during the 1986 playoffs.) Showtime is crammed full of hilarious, and occasionally moving, stories about the ’80s Lakers. On a White House tour after one of the Lakers’ championships, taking in the portraits of ex-presidents, shooting guard Byron Scott wondered aloud, “Why are there only white people on the wall?” Riley’s predecessor Paul Westhead, a former English teacher at the University of Dayton, once suggested Johnson get the ball inside to Abdul-Jabbar during a timeout by quoting Macbeth: “If it were done when ’tis done, then ’twere well it were done quickly.” Legendary Lakers General Manager Jerry West flees to the bathroom, crying, after he cuts from the team longtime Laker Jamaal Wilkes, emotional about how Wilkes, whose wife worked with his wife, would have to go home and tell his spouse that he no longer had a job.

Unlike many other sports dynasties, the Lakers’ unparalleled 1980s run ended all at once, on Nov. 7, 1991. Magic Johnson was in Salt Lake City preparing for an exhibition game when he was urgently called back to Los Angeles by team doctors. There they shared the shocking news that he was HIV-positive.

“I really can’t think of a more improbable story in our lifetime related to sports than Magic Johnson has HIV. We all assume he’s going to die in a couple of years,” said Pearlman. “We all imagine him with lesions and the weight loss and hooked up to an IV, and the horrible, horrible heartbreak that came upon so many people with HIV.” Showtime ends with appropriate abruptness, as the real Showtime did, with Johnson’s announcement, and the stunned responses of his teammates and onetime rivals. Kurt Rambis, a former teammate of Johnson’s then with the Phoenix Suns, left for Los Angeles, telling his coach, “ ‘I have to leave. … I can’t tell you why. You’ll just have to trust me on this one.’ ”

Pearlman understandably defers on sharing the tentative subject of his next book, since he has yet to sign a contract for it. But he does share, unexpectedly, that his dream project is a biography of the tragically short-lived Blind Melon lead singer Shannon Hoon, who died of a drug overdose in 1995. “I thought this band made some genius music. It’s this brilliant music that nobody ever really appreciated in a big way. And now they just live on the fringes of ’90s music history because of the girl in the bee suit from ‘No Rain.’ ” Given his preference for sporting stories with defined beginnings and endings, perhaps Hoon’s story offers a similar arc in a different field: a brief burst of achievement, bookended by tragedy. For Pearlman, telling stories about flawed heroes is less a matter of digging for dirt than an opportunity to revisit a magical past: “It’s not about the dysfunction, it’s more about the nostalgia.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Saul Austerlitz is the author of Sitcom: A History in 24 Episodes from I Love Lucy to Community. His Twitter feed is @saulausterlitz.

Saul Austerlitz is the author ofSitcom: A History in 24 Episodes from I Love Lucy to Community. His Twitter feed is @saulausterlitz.