The Great Riffer

ABC’s and P’s & Q’s, in Jeremy Sigler’s latest book of poetry, ‘Goodbye Letter’

I’ve always found Jeremy Sigler to be a bit of a Jekyll-Hyde type. As an art critic—and Tablet readers know him well in that role—Sigler comes across as droll, edgy, tough-minded, cutting, sardonic, and sometimes, as in his recent riff on Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice, outrageously funny. He is willing to take on the famous and established and show their hypocrisies and weak points with great humor, panache, and a dose of self-deprecation. Sigler—and this is increasingly rare these days—knows how to laugh at himself; he never takes himself too seriously. I have read some 50 essays he has written for Tablet and have found myself smiling, nodding, and sometimes laughing out loud at his commentaries. Go, Jeremy, go!

Sigler the poet, on the other hand, is an austere minimalist attracted to concrete and sound poetry, a poet who writes under the sign of such artist-poets as Carl Andre (Sigler edited the recent DIA Foundation catalog of Andre’s work and he has also produced a controversial book called Carl Andre: Love Poet in Marxist Overalls), Aram Saroyan, Henri Chopin, and Gerhard Rühm. His new book, Goodbye Letter, has, right in its center, a signature of 16 blank pages that bears the title “Stethoscope Poem.” This conceptual piece takes as its source René Laënnec’s 1816 explanation that when “I rolled a quire of paper into a sort of cylinder and applied one end of it to the region of the heart and the other to my ear ... I could thereby perceive the action of the heart in a manner much more clear and distinct than I had ever been able to do by the immediate application of the ear.” So Sigler provides 16 tear-out pages, each with a narrow perforated fold, that can be rolled into a cylinder and hence simulate the stethoscope. The resulting “poem” can be read as an homage to the poet’s father, a physician in Sigler’s native Baltimore. Or, since the stethoscope is designed to hear the subject’s beating heart, the blank pages may be construed as an ongoing love poem.

Is this too easy a game? A mere gimmick using up a wad of thick white cardstock? Sigler the critic might well think so. In a mordant essay titled “I Destroyed a LeWitt,” he begins with a curious account of his tenure as assistant to the conceptual artist Lawrence Weiner. Asked to paint the walls of the artist’s studio, he realized that he’d have to do a frame around a wall drawing by the famed father of conceptualism Sol LeWitt, and that the white paint he was using wouldn’t match. What to do? When he consulted Weiner, the latter shrugged and said, “Go ahead and paint right over it.” The point was that LeWitt’s geometric wall drawings were executed according to a strict numerical system that anyone could replicate. So Weiner planned to call LeWitt’s assistant and have him come over to redraw the work as soon as possible.

Sigler’s little story serves two purposes. For one thing, he wants to remind the reader that LeWitt took at face value Walter Benjamin’s prediction that “in the Modern era, a work of art was destined to become a mere copy of a copy of a copy.” But more important (and less obvious), Sigler uses his little anecdote to distinguish between LeWitt’s mechanical drawings and the artist’s less-well-known and modest little books, on exhibit at a retrospective called Book as System at Printed Matter in Chelsea. This modest exhibition, Sigler convincingly argues, is much more impressive than, say, LeWitt’s massive 2007 retrospective at that “pantheon of minimalism,” Dia:Beacon—an exhibition that, Sigler recalls, “left me with a bad taste in my mouth.” The actual installation process for that show turned the galleries in question into a kind of battle zone, resembling, according to one curator, “an air traffic control room where, in a large string-gridded environment, workers were plotting and cross-checking coordinates across a vast Cartesian abstraction.” And, asks Sigler, “Where was LeWitt while all this hard work was going on? Playing chess? Catching a matinee in a quiet dark theater? At a baseball game?” Perhaps, the critic concludes, one LeWitt wall drawing per show is enough. “Even two may be ostensibly too many. An exhibition of multiple wall drawings, temporary as they usually are, can’t help but distract me with anxiety for wasted human labor—the army of students and/or aspiring plebs assumed to follow King Solomon’s instructions.”

In this context, it is LeWitt’s modest little artist’s books that stand out for their superb artistry:

LeWitt used the book medium not merely to draw, but to draw things out. Before there was any such thing as a personal computer, he used the book system to manipulate the fundamental data of line, value, shape, color (formalism). His line processing gave him a kind of extender, an elaborator, and an exhauster for each and every whim, as if a book’s 20-some pages (with recto, verso, cover, spine) allowed him to expand the most innocent of thoughts into a walloping ballad of metrical verses and technocadence. Each minimal nibble taken to an unprecedented harnessing of unforeseen potential.

Lineate this lyric passage, with its assonance (“minimal nibble”) and serial repetition (“unprecedented,” “unforeseen”), and it could certainly be included in a collection of Sigler’s poems. Indeed, his 2017 collection of prose poems, My Vibe (Spoonbill Books), reviewed for Tablet by Julian Kreimer, consists of short anecdotal and generally absurdist tales, whose tone and valence recall the critical pieces. Here is a sample (the title is always the first word or two of the story):

The

Schindler House. I love to think of that house. Barely there, really. On King’s Road. Awaiting the quake.

It began to rain the last time I read in the grassy courtyard. The first few drops landed in unison with my first few words.

Brandon told me it sounded more like a chant. It’s true. I was exploring a certain tonal register.

I looked out at the audience in their fold-out chairs set up so nicely on the grassy yard. “How about if we switch places?” I said. And the audience stood up, left their seats and came under the eave. And I walked out and sat in one of the chairs, with my stack of poems, which were quickly becoming spattered with soft drizzle.

Someone kindly handed me an umbrella. It was pure theater.

Trivial as this account of Jeremy’s ill-fated poetry reading seems, its subtext is subtle. The house on King’s Row in West Hollywood, designed by the famous architect Rudolf Schindler in 1922, was meant to be a community home with shared living spaces. John Cage, for one, was a resident in the early ’30s. Architecturally novel but badly constructed, the house has witnessed frequent roof leaks and cracked walls, even after some remodeling. In the 1990s, the Viennese MAK took it over and turned it into an avant-garde art center but hardly a comfortable or accessible one: the ceilings are so low that tall people have to stoop, and parking in the neighborhood, now one of high rises and condos, is impossible. So what happened to Jeremy at the Schindler House is hardly surprising and gives him the opportunity to satirize both the venue and the whole process of the poetry reading, with its theatrical separation of reader and audience.

This tale, in any case, could be published side by side with the brilliant essay “Eli Broad’s Selfie-Dome,” Sigler’s brilliantly scathing demolition of the new Broad Museum in downtown LA along with its billionaire owner. Here is the opening:

I generally don’t feel well in a museum until I’ve drifted through its highly surveilled architectonic labyrinth and followed the exit sign back outside. Indeed, the nicest part of my visit to the Broad, Los Angeles’ latest attempt at a world-class modernist treasure hoard, was the time I spent out on the museum’s spacious lawn, where I could sip a $5 iced coffee through a green straw, compulsively checking and rechecking my iPhone and reviewing the many selfies I’d just shot inside the museum in front of legendary paintings by Andy, Jasper, Bobbie, Cy, Roy, Ellsworth, and Ed. (At the Broad, photography is permitted—dare I say even encouraged.) The backdrop of iconic 1960s paintings looked great, and the art from the ’70s, ’80s, ’90s, and onward, a little less so. But the real question: How did I look? I could have sworn I was skinnier on my way in there.

Reading this paragraph, I chuckled with a shock of recognition: Sigler has so beautifully caught the sheer crassness of Eli Broad’s new monument to himself, with its faux greenery and its inclusion of all those famous artists with whom Broad is on a first-name basis, but whose work (the essay later makes clear that Broad owns mostly their second-rate paintings) functions primarily as a backdrop for selfie-taking by the teenagers snaking on long lines to get into this “free” museum—a structure designed by the “starchitecture firm Diller Scoffidio & Renfro, [which] comes across as part Breuer and part Beinecke, with a splash of Bat Cave.” “I felt,” Jeremy tells us, “like I was entering an Apple Store for an appointment at the Genius Bar.”

The comparison of “museum” to Apple Store sets the stage for Sigler’s devastating critique of the whole Broad project. I recall that when the museum opened in 2017, the reviews were mixed with respect to the collection but enthusiastic about the architecture and the whole enterprise, evidently fearing to attack as powerful an art-world figure as Eli Broad. Sigler gets away with it because he is very much in command of the facts—his biographical account of Broad the young real estate speculator in Detroit is detailed and devastating—and because his word play is so funny:

If you change the order of the letters ‘B-r-o-a-d,” you get the word “b-o-a-r-d,” and Eli Broad is nothing if he isn’t chairman of the board. He sits, or has sat, on the boards of MOCA and LACMA; he rescues boards in financial crisis by donating tens of millions of dollars (in big business, this is known as a “hostile takeover”); he gets the right people onto the board, the wrong people off the board, on behalf of all those who are “on board.”

It is similar word play and deployment of repetition that we find in Sigler’s poetry. In the early Crackpot Poet (2010), we find short minimalist lyrics like “Paperback Palms”:

The tide

known to

be up

for the

ride

decides

to sit

one out

to bite

barnacles

under boats

This nicely captures the actual movement of the tide, using rhyme on the soft d (tide/ride/decide) and then consonance on the hard t sound (sit/out/bite), culminating in alliteration of b’s (bite/barnacles/boats) that almost obscure the return of the d sound of “under,” so that the ebb and flow of the water is made palpable before our eyes.

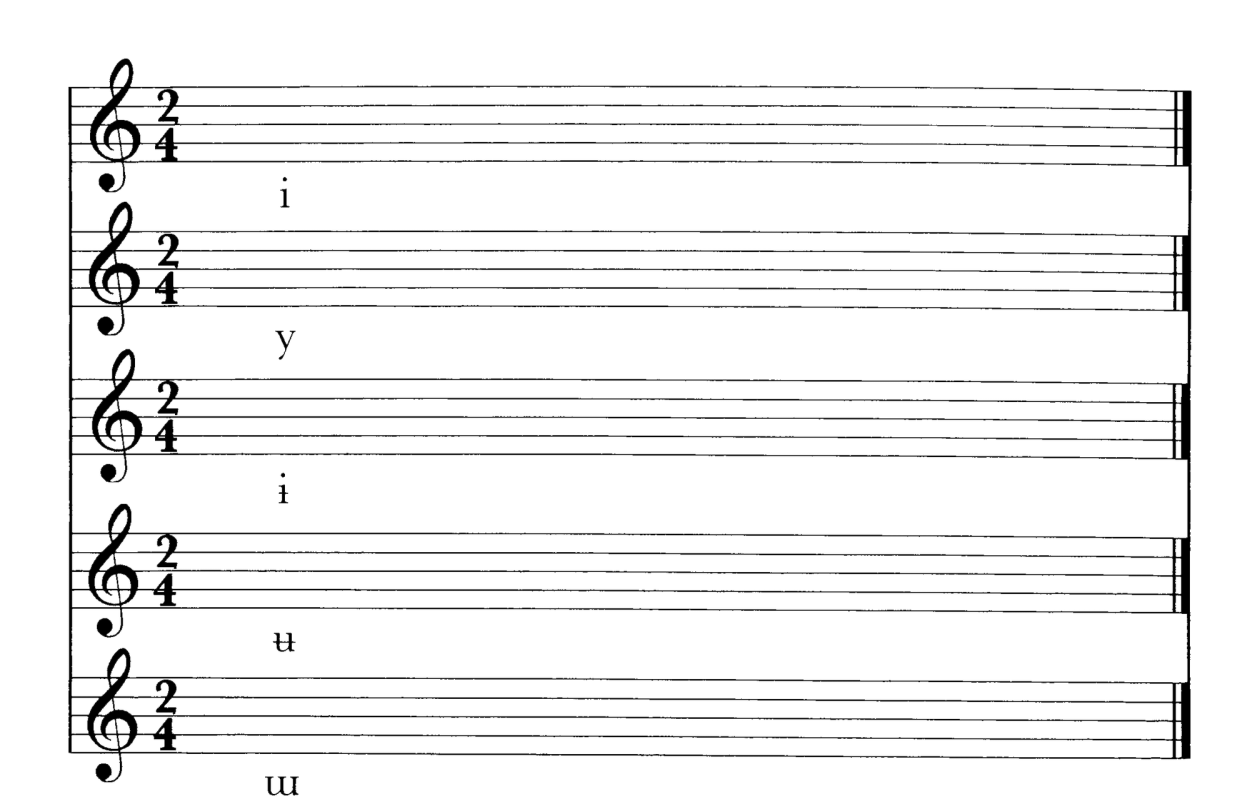

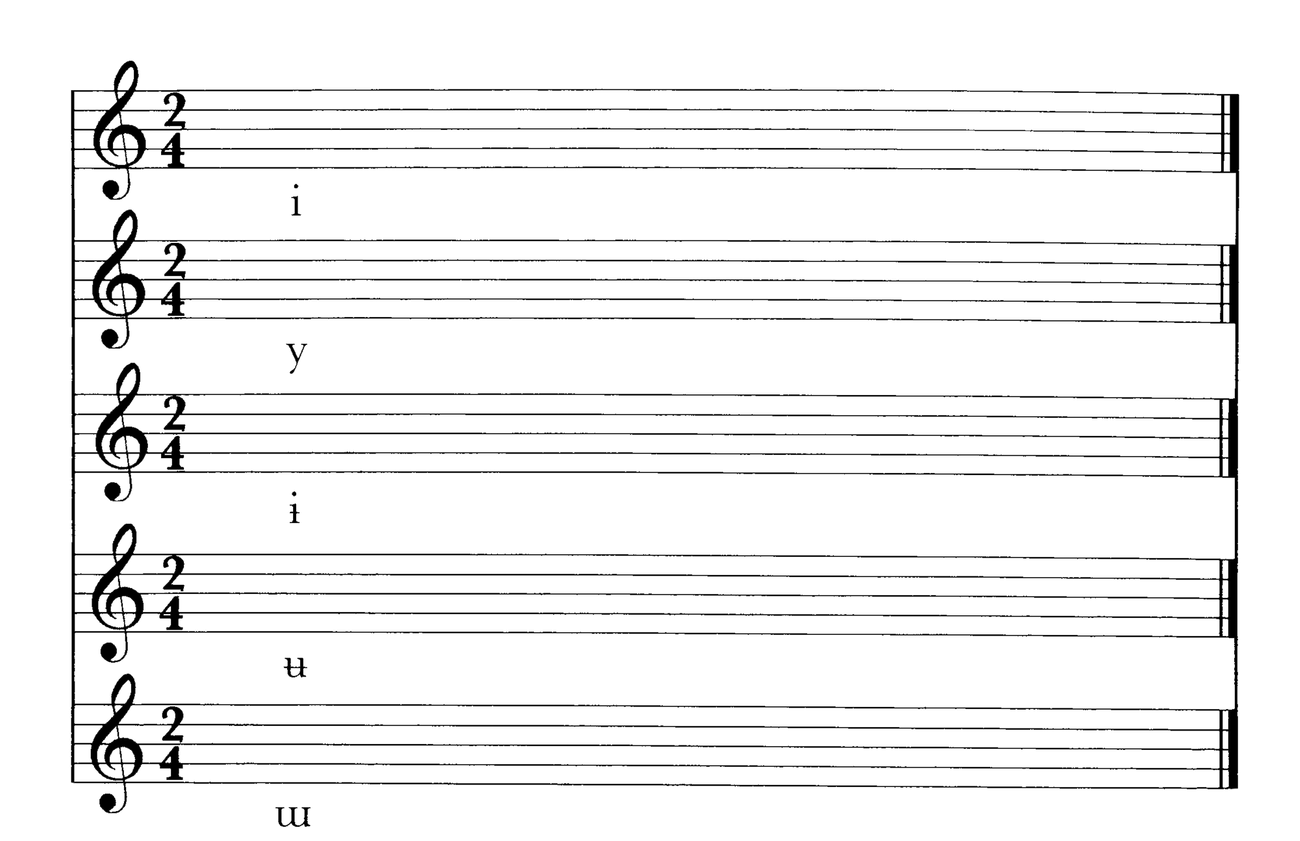

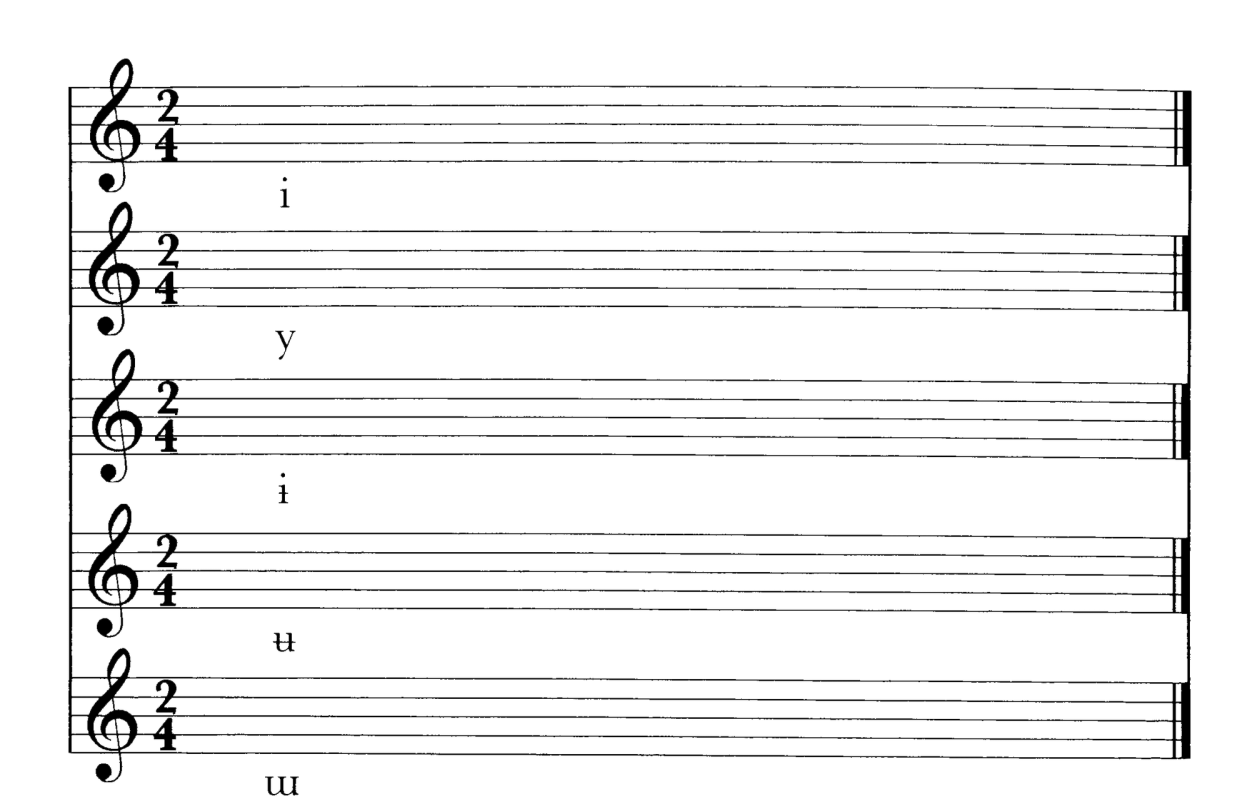

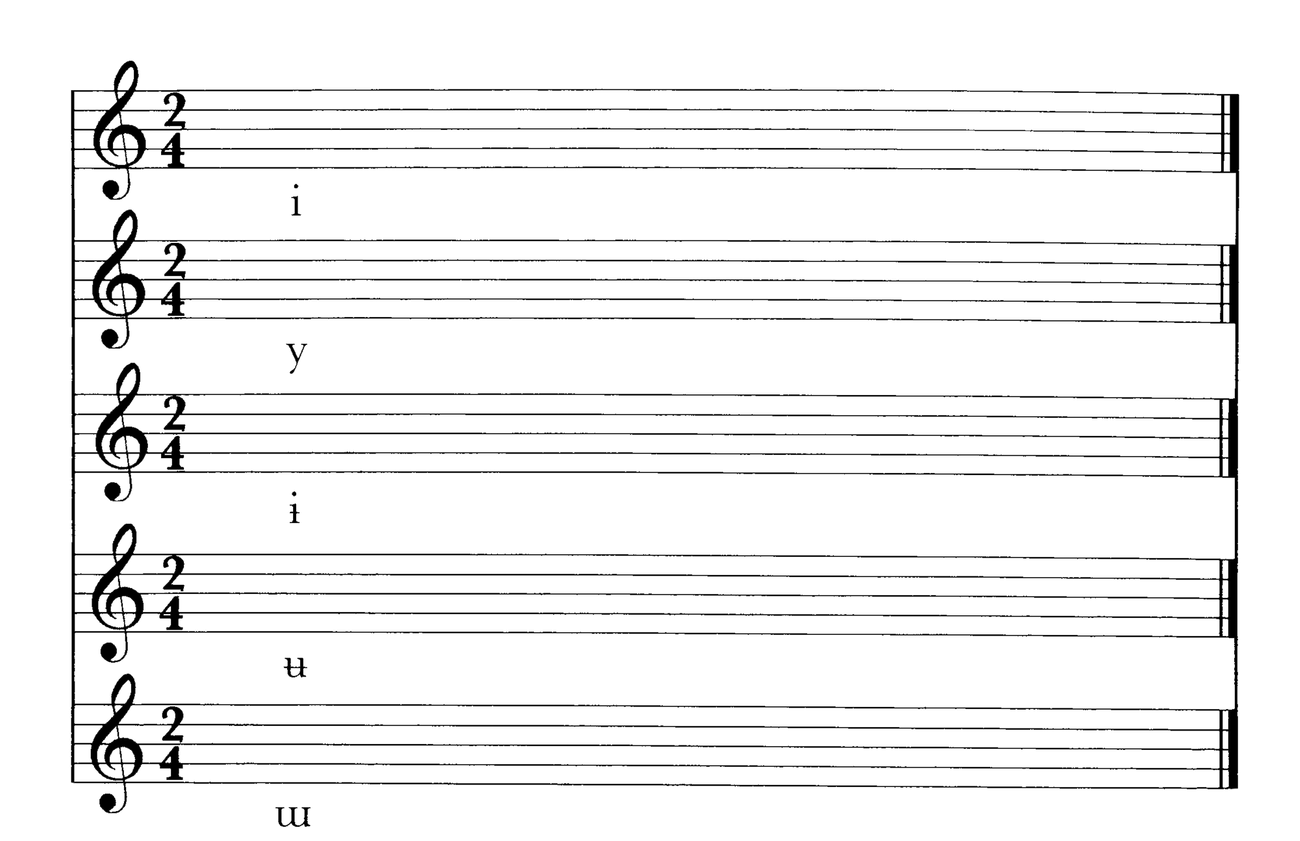

But in the 2014 alphabet book ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ, Sigler takes things a step further, now reproducing word games like continuous alphabets that elide certain letters, so as to form new secret sequences of words, for example, “F-L-E-C-K-S O-F G-L-I-T-T-E-R P-A-R-A-D-I-N-G B-E-A-M-S O-F F-U-T-U-R-E” in No. 4 or “J-E-R-E-M-Y S-I-G-L-E-R” on the book’s last page. It’s fun to play the game of seeing the neutral alphabet reveal its hidden stories, but the joke also wears a bit thin. And the same holds true for some of the sequences in Sigler’s elegantly produced new book Goodbye Letter—a book of alphabets, glyphs, visual poems (e.g., his carefully spaced “p-o-v-e-r-t-y,” morphing into “p-o-e-t-r-y”), and even musical scores.

The first of the alphabet sequences, “The Common Phonabet,” matches letters and sometimes numbers, either individually or in small units, with their phonetic equivalent, as in:

Q cue (or Q que, Q queue)

EZ easy

9T ninety

FMN8 effeminate

The next sequence, “GRAMMATICALS,” arranges the letters in visual units and then provides a “translation” so that

I

I

N

EZ

QT

becomes “I eye an / easy / cutie.” Sigler spins variations on these little units, and oral rendition of the letters produces new phrases, rather as in a game of Clue or Scrabble.

But is this enough to make a poem? Sigler’s model here would seem to be Carl Andre, whose typed blocks of letters, ugly and ordinary to the eye, reveal all kinds of surprises, as when the “ELBOW” print block, with no spaces between words, is seen to spell BOWEL just as easily.

Poetry, in other words, always has an element of surprise. And indeed there are some vintage witty conceptual pieces in Goodbye Letter, like “Voice of a Generation,” with its mock tabulations, giving us such “information”:

Generation Z 2001-2018 Age 5-17

Wouldn’t you like to know what common traits the 5- and 16-year-old Generation Zers share? The second table, “Voices of an MT [Empty?] Generation” tabulates material from 1965 to 1979, only to show that nothing has changed, the numbers, in the 3 millions, fluctuate so slightly that the chart emphasizes the curious mindlessness of the interrogated subjects as well as their interviewers.

But the third item is the funniest. “The Voice of a Generation,” reminds us that Sigler is always ready to laugh at himself:

51, 298, 346

- 1

51, 298, 345

Whose voice, this little figure asks us, is not expendable? And what is the point of all those tabulations that bombard us day after day?

Perhaps it is the feeling of expendability that led Sigler to place, on pages 27-31, a dialogue with Andrew Leland, excerpted from a KCRW podcast of 2018. At the outset, Leland explains that Sigler has been experimenting with the sound of single phonemes and has, most recently, “written a poem entirely absent of words.” Thus his “Phonemadrigal” is “not even a second long.” “To make it, Sigler layered these phonetic sounds on top of each other, to squash language into this single linguistic experience, almost like a punctuation mark.” And Leland explains:

Sigler’s “artistic journey began with traditional poetry and has moved into this experimental territory, where the poem itself has almost entirely been dissolved. ... He’s imagining this future where texting and email and other kinds of electronic communication will make spoken conversation obsolete.

Sigler responds by speculating

What if human language is just something we’ve been using, essentially a flawed technology, that will be replaced by better technologies for communication?” ... [what if] a simple conversation were no longer something we had access to in our daily lives. Instead, let’s say, the technology goes mind to cloud to mind—essentially telepathic communication all handled through algorithms and mathematic machines in order to take a thought from one brain to the other. ... So I kind of thought ... a poem would be a sort of endgame, as if this was gonna be my last poem, and the last poem ever in ... [ellipsis Sigler’s] the human technology of language. ... I think a little bit of Beckett, where there’s an endgame.

Read straightforwardly, this is just plain sophomoric. No, Jeremy, you haven’t written the last poem, and no, with all the algorithms in the world, there are still conversations and language is not about to go away. On the contrary, surely the current problem is that there is too much language—all those blogs and websites, and long citations on Facebook, and scholarly articles published on very specialized topics—not to mention too many slim volumes of poems! Today, as Walter Benjamin so presciently predicted, everyone is an author. Besides, as Sigler himself made clear in “The Voice of a Generation,” he is not at the center of the universe. Even if he never wrote another poem, at this very moment in São Paulo or Seoul, Aleppo or Abu Dhabi, someone is writing a poem and hoping to publish it.

Sigler’s naughty Hyde persona knows this perfectly well. At the end of the podcast, he admits that his own ultimate poem can only be a penultimate one. “That must be why the word ‘penultimate’ exists; it’s all these idiots who think they’re gonna come up with the ultimate poem. [Sound.]”

So much for all the speculation on “the state of poetry.” Let’s hope that Goodbye Letter is indeed a penultimate text and that, before long, Sigler will produce another poetry book, riffing, as only he can, on his daily trauma and erotic encounters, real or imaginary. In the meantime, I’m wondering how in the world he can produce another rumination on pandemics that can outdo the comedy of “Death in Venice Beach.”

Marjorie Perloff is Professor Emerita of English at Stanford University and Florence R. Scott Professor of English Emerita at the University of Southern California.