Jerry Lewis Did Kol Nidre in Clown-Face on Yom Kippur, May His Soul Find a Shining Piece of Paradise

Rokhl’s Golden City: The Jazz Singer, and a legendary klezmer drummer bubbe

Git yontev, git yor. It’s that time of year. If you’re the synagogue type, you’ll have the opportunity to attend the Yizkor memorial service that takes place four times a year, including on Yom Kippur.

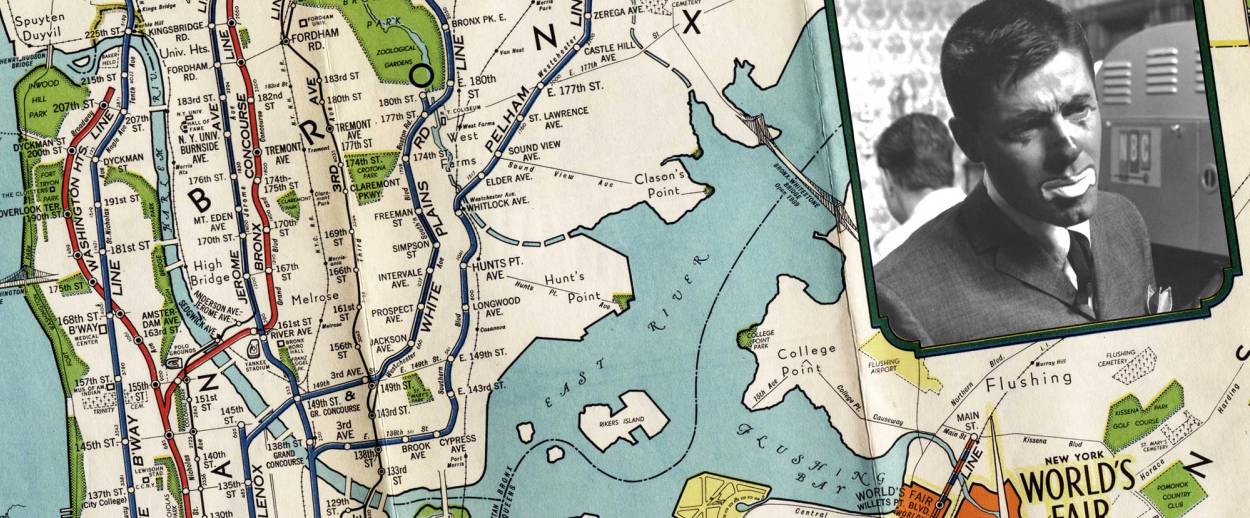

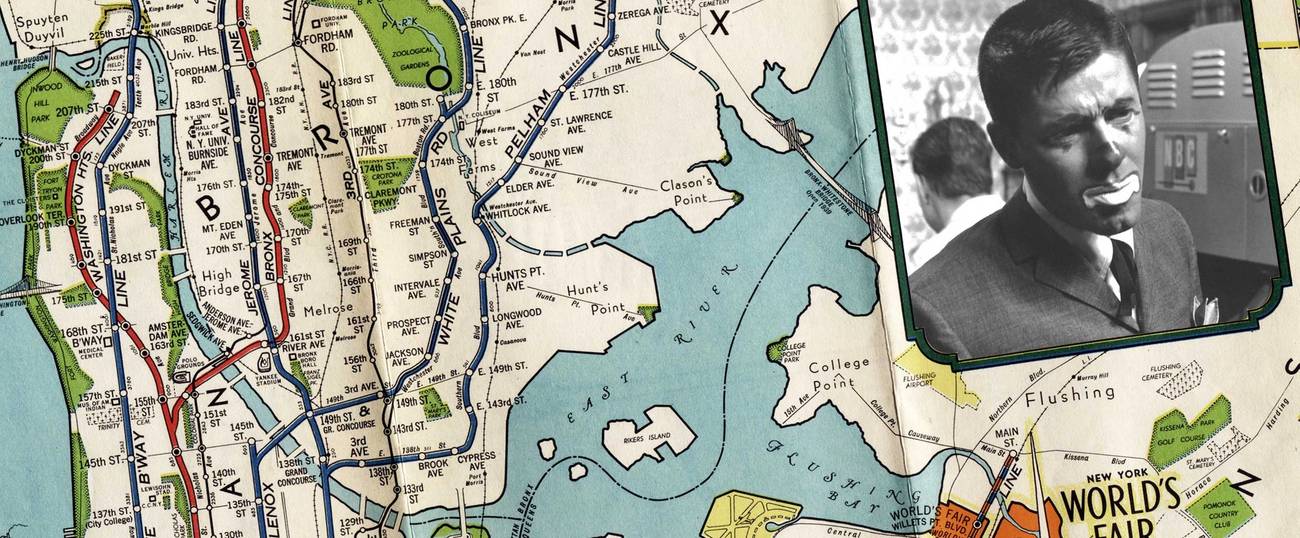

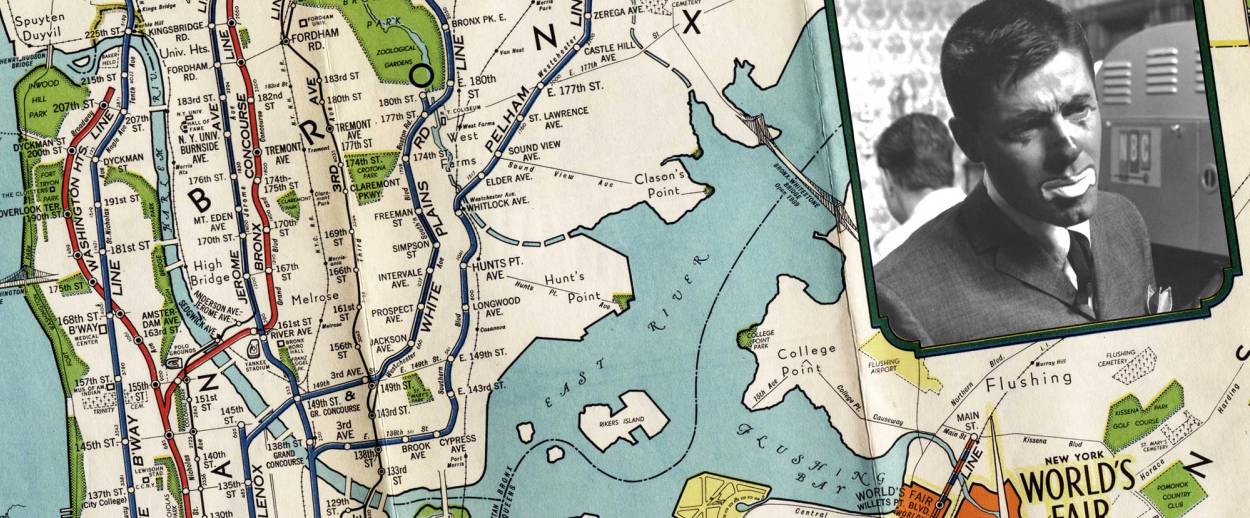

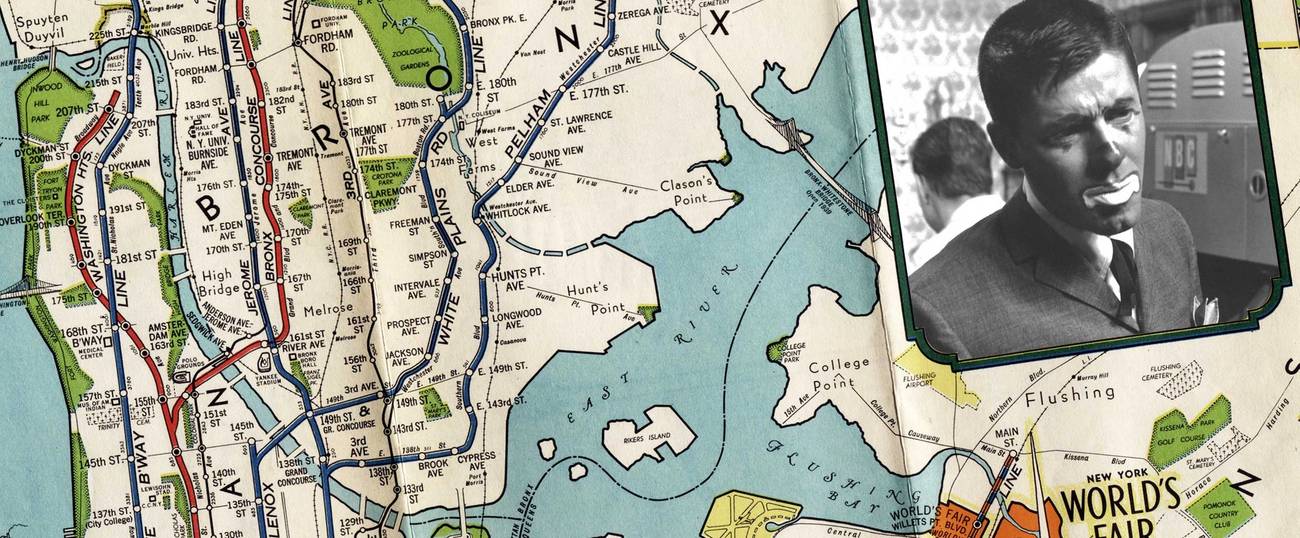

Of all our recently departed, Jerry Lewis (z”l) has been on my mind the most. I blame Shane Baker. Shane comes over to my place for a “study date” and four hours later we’ve watched every dirty vaudeville video on YouTube and not written a word. This last sesh, though, turned me on to something I didn’t even know existed—a 1959 Jerry Lewis TV-movie take on The Jazz Singer. But since it’s Jerry, and it’s 1959, at the climax, instead of singing Kol Nidre in blackface he appears in … clown face. It’s the kind of thing that is hard to believe until you watch it. Now I’m having trouble forgetting it.

Everyone’s khalishing for Jerry’s lost Holocaust atrocity The Day the Clown Cried. Honestly, this Jazz Singer is so much more interesting. Molly Picon, the petite giant of the Yiddish stage and screen, plays Jerry’s mom. The voice of Fred Flintstone (Alan Reed) is his Uncle Nat. And while the script is clunky in parts, damned if I didn’t have tears in my eyes as a forlorn Jack/Yosl kisses the mezuzze on his parents’ apartment after being thrown out.

The most intriguing part of this Jazz Singer is its use of musical motifs. In the first scene, we see Jack Robin doing his comedy and jazz nightclub routine, including a song called “This Is My Town.” Dissolve to Jack/Yosl’s elderly khazn father tutoring a young boy singing a Hebrew tune with a startlingly similar melodic structure. Later on, when Jack returns home for his father’s birthday celebration, Jack sings the same “jazz” version a cappella. Whether it’s an act of unconscious rebellion or miscalculated homage is unclear. The result, in any case, is not a happy one.

The Hebrew tune in question is called “Israel’s Keeper” by A.W. Binder. Binder is a fascinating character, an American-born composer and cantor who revolutionized Reform liturgy and, apparently, had a knack for writing ancient (or at least authentically Eastern European) sounding tunes.

The “jazz” tune based on Binder’s melody is by Jack Brooks and, as far as I can tell, was composed for the movie. Using the Binder tune is a terrifically intelligent piece of filmmaking for a one-hour TV movie that was shown exactly once (the day after Yom Kippur, 1959). Then again, as much as Lewis played the buffoon on screen, he was known to be an obsessively meticulous craftsman when it came to his directing and solo work. Zol er hobn a likhtikn gan eydn/may his soul find a shining piece of paradise.

As I write this homage to Jerry Lewis I’m processing another death, this one much closer to home. On Monday we learned that we had lost Elaine Hoffman-Watts. Elaine was a drummer, the first woman to graduate as a percussionist from the Curtis Institute of Music in 1954. She was also a music educator, funky matriarch of the global klez community, and an esteemed member of a legendary Philadelphia klezmer dynasty. Her daughter, Susan, with whom she often collaborated, is one of my favorite trumpet players. In a music scene so profoundly marked by discontinuities and absences, Elaine embodied connection and wholeness. Her very presence always felt a little bit miraculous.

Elaine’s impact on our community was enormous. She taught a popular class at KlezKanada called “Girls Don’t Play Drums,” whose name alone made me want to pick up a poyk. My friend Josh Dolgin (aka Socalled) sampled Elaine on his 2005 Socalled Seder album. Yesterday on Facebook Josh wrote that Elaine was “the reason I fell in love with klezmer—and found a place in my own culture.” Can there be a better tribute? May her neshome have an aliye.

One last thing. I caught Arthur Szyk: Soldier in Art on its opening day at the New-York Historical Society and want to make sure everyone sees it because, wow. As far as I know, Szyk didn’t speak Yiddish. At the time and place Szyk came of age, interwar Poland, Jews, especially urban Jews, (Szyk was born in Lodz), were becoming increasingly Polonized. People were looking for ways to integrate their Jewishness with a sense of Polish belonging. It’s that search for a new identity, for new modes of Jewish expression, that is so compelling for a Yiddishist like me.

For some, that integration was done in Yiddish. For example, the Landkentenish movement took Jews out into the Polish countryside and showed them how to be at home in the land. For Jews like Szyk, that nationalist feeling took other forms. One of his famous artworks is The Statute of Kalisz, an illuminated illustration of a set of medieval laws granting privileges to Jews.

Once Szyk left Poland, his art reflected the social-political concerns of his new home, specifically the American fight against fascism as well as the fight for a Jewish state, themes well exemplified in the new N-YHS show. Szyk’s art is a gorgeous mix of medieval detail and modern themes and deserves to be seen up close and personally. Don’t miss it.

Watch: I had selfish reasons for wanting to hang around Elaine Hoffman-Watts. My dad’s family is from Philly, and she talks just like my Philly relatives. Having never known either of my grandmothers, I liked to imagine they were a little bit like her: warm, smart, and hilarious.

Visit: Arthur Szyk’s Soldier in Art at the New-York Historical Society through Jan. 21, 2018. (Open late Friday nights.)

Buy: Looking for a unique wedding present? Buy your favorite couple a set of Szyk Haggadot and they’ll love you forever.

See: When reality confounds satire, only absurdity will do. There’s still time to take in New Yiddish Rep’s Nozhorn.

Listen: to Jerry Lewis’s recent interview with Marc Maron. Jerry says that his vaudeville-performer parents did do Yiddish material, but only when they absolutely had to.

ALSO: Correction to my last column: Daniel Kahn’s new album, The Butcher’s Share, doesn’t even come out until mid-November, so I retract my irritated harrumph at not having received a copy yet. Sorry, Dan…

Rokhl Kafrissen is a New York-based cultural critic and playwright.