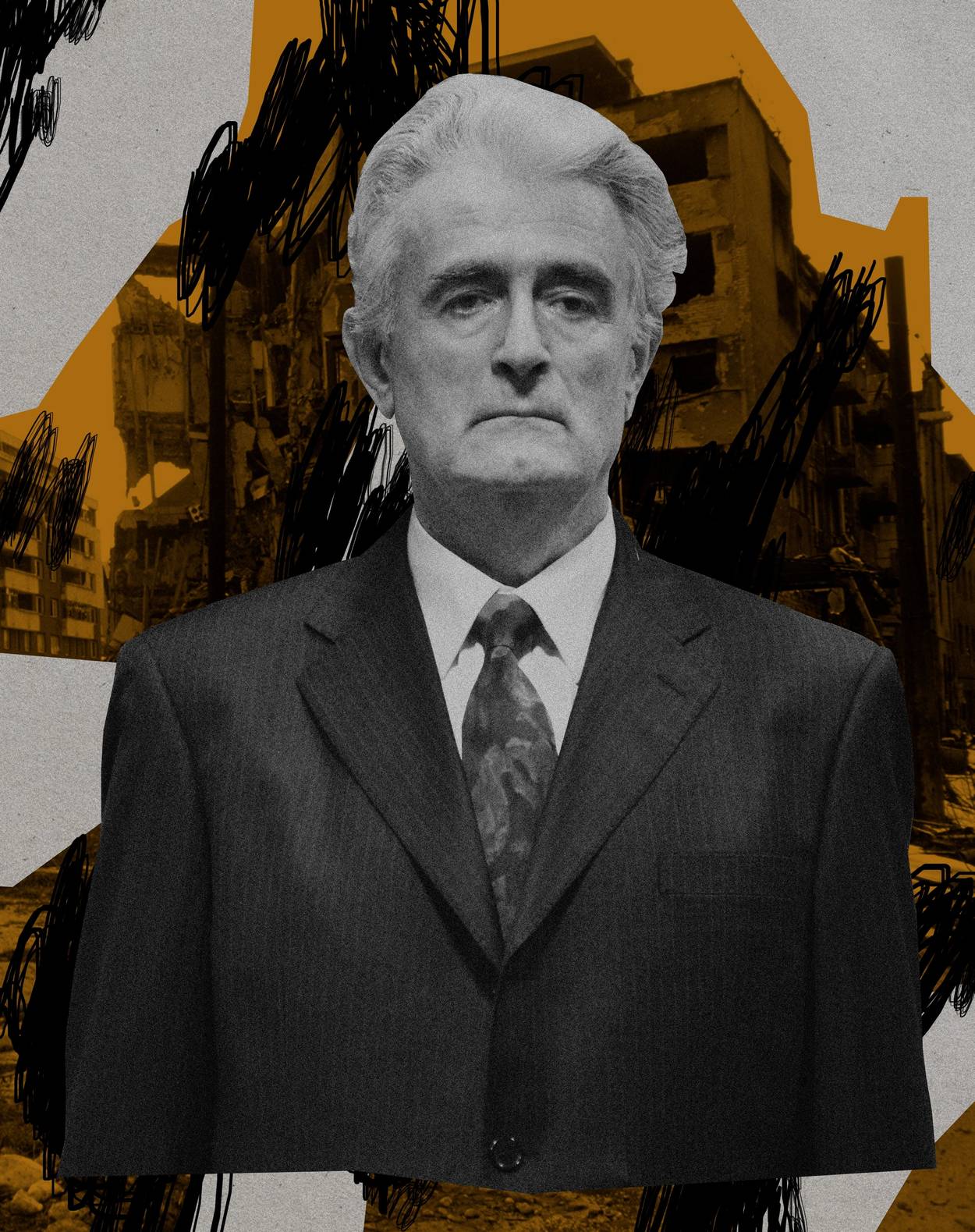

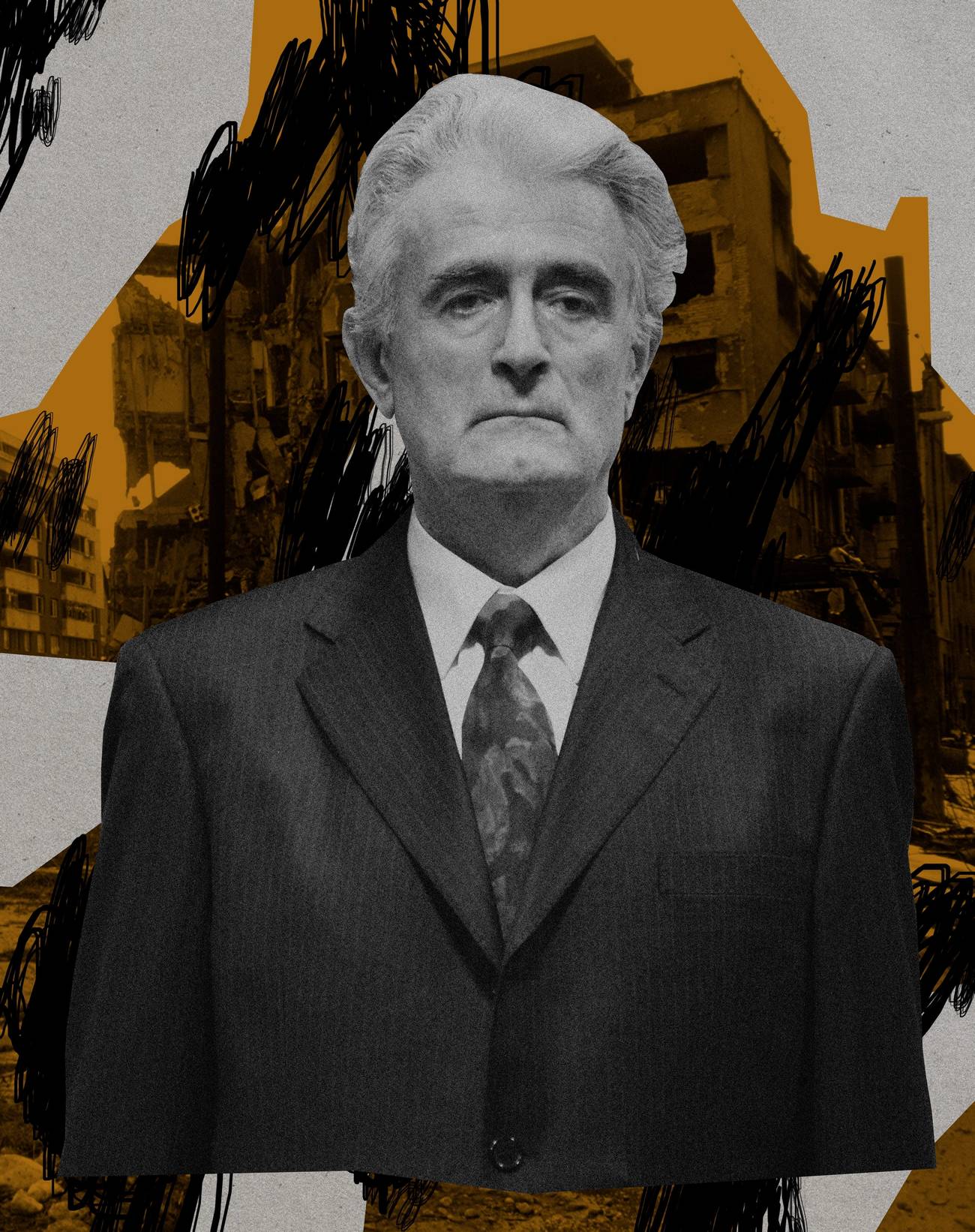

The initial response to the publication at the beginning of this year of My War Criminal: Personal Encounters with an Architect of Genocide, terrorism scholar Jessica Stern’s book on jailed Bosnian Serb leader Radovan Karadžić, was negative enough for her publisher to cancel all promotion in its wake. Karadžić was a key figure in the genocide of Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims) during the Yugoslav Wars of the early 1990s. While Stern expected some people to be “really unhappy” that she was interviewing “an evil person responsible for a genocide,” she had assumed those who would go after her would be Russians or Serbian nationalists. But the outcry in fact originated mainly from figures in the Bosniak community, who began to comment on the book on social media after an excerpt was released in The New York Times prior to the book’s publication in January.

Her publisher made the decision to “[cancel] absolutely everything” after a lunch “with two other publishers who were facing similar results from the so-called cancel culture.” One Bosnian American activist celebrated the termination of scheduled bookstore discussions for this “hagiography of a genocidal maniac,” and led a fresh call to drop future events. Stern “understood” the publisher’s decision, and blamed a lack of attentive reading and manipulative social media algorithms for the pile-on: “People respond to each other’s social media posts without necessarily reading. They don’t even bother to read [the NYT excerpt]; they’re responding to what someone else says and they have no idea they’re part of a mob.”

But it soon became clear that no investigation was needed to explain why the book received a negative early reception. Stern had written a bad book. But dreary, unedifying calls for a boycott drowned out the possibility of her being challenged in open, intelligent discussion.

Stern, the daughter of a Holocaust survivor who died when Stern was 3, has previously attempted to explain how “terror had become [her] central preoccupation.” In her 2010 memoir Denial, she revealed that she was raped at gunpoint aged 15, having also been abused by her grandfather as a child. After initially studying chemistry (“I liked that the answers were either right or wrong”), she became “an expert on terrorism.” Her fascination with “the secret motivations of violent men” would lead to a state where “instead of feeling terror,” she “studied it.”

After finishing her second book on the subject, Stern began to contemplate her own experiences and the links between abuse, trauma, and terrorism. In the preface to My War Criminal, she notes that her unawareness of “the sensation of fear” in the presence of armed men, and tendency to transform “almost as if I were one of them” during interviews with violent men, was her “making creative use of the sequelae of childhood trauma.”

Yugoslavia (est. 1918)—a country formed of six constituent republics that collected various peoples of the Balkans, southeast Europe—began to disintegrate in 1991. As mutual fears, tensions, and ambitions escalated, each component began to break away. Slovenia became independent after a 10-day war. Macedonia (now North Macedonia) departed from Yugoslavia peacefully. (The Kosovo question would be activated later.) In the process of forging ethnically homogenous states, killing and expulsion engulfed Orthodox Serbs, Catholic Croats, and Muslim Bosniaks. To refer to these events, “ethnic cleansing,” a term that was apparently originated in Serbo-Croat during the conflicts of World War II, entered official international language through a 1992 U.N. resolution.

In a referendum that was boycotted by ethnic Serbs that same year, 99% of Bosnian Muslims voted to secede from Yugoslavia. Fears of persecution, grounded in the sweltering paranoia of Serbian politics plus superior Serb military means and support from Belgrade, explains the strength of the result. Anti-Muslim propaganda was rampant, encouraging Bosnian Serbs to arm. By the time of the referendum, Serbs had already organized militarily, launching autonomous regions in Croatia and Bosnia.

All three sides were under some degree of threat, and each suffered and committed atrocities. But Serbian aggression was the main driver of death, rape, destruction, and pillage in the Yugoslav conflicts of the early 1990s. After years of inaction and botched action, during which an estimated 100,000 people died, belated Western intervention against the Serbs in 1995 ended the war. Karadžić’s Serb forces committed the single worst massacre of a broader campaign of ethnic cleansing against Bosnian Muslims: the murder of 8,372 Bosniaks at Srebrenica.

Jessica Stern attempts to move beyond history without accepting that she needs first to understand it, since even the most fanciful or psychotic departures are derived from material reality.

Serbian President Slobodan Milosević was charged with war crimes by the International Criminal Tribunal for Yugoslavia in 1999 following NATO bombings, which again targeted Serbian forces (and killed hundreds of civilians). Since then, many important figures from the Yugoslav wars have been prosecuted, including Karadžić. Srebrenica was ruled to be an act of genocide by the ICTY in 2004 and the International Court of Justice in 2007. But as Tim Judah wrote in his powerful history of the period, the fact that most of these international indictments relating to the Yugoslav conflicts were of ethnic Serbs “did not lead the Serbs to the conclusion that their side had committed more crimes but rather reinforced their prejudice that the whole world was against them.”

Serbian nationalist ideology had pre-built capacities for genocide denial. In 1986, a leaked document produced by Serbian intellectuals and artists (and rebuked at the time by Karadžić) stated that there was a “genocide” underway against Serbs, pointing to anti-Serb threats in every corner and dimension of Yugoslavia and advocating unilateral action in case of state collapse.

The Serbian reading of history, while paranoid, was grounded in past atrocities. During WWII, Croat political parties and paramilitary groups, in alliance with the Nazis and with some Bosnian Muslim participation, committed large-scale massacres and expulsions against Serbs. These events were still well within living memory of ethno-national decision-makers in the Balkans during the early 1990s. Tito’s long rule in post-war Yugoslavia was premised more on submerging these crimes than prosecuting them. Yet resentments over past injuries were weaponized by Serbian nationalists in the new context of Yugoslavia’s collapse. As David Rieff wrote in 1995, the fear and aggression expressed by the Serbian intelligentsia exploded into the mass murder he observed as a reporter: “A crucial factor in the success of ethnic cleansing was the prevailing belief among Serbs that they were the injured parties, engaged in a defensive war.”

Stern unsurprisingly finds Karadžić fully unrepentant, marshaling a predictable set of tactics in the service of a grimly familiar set of delusions and lies. But Stern’s psychologizing approach to Karadžić muddies historical understanding while providing little fresh nourishment or stimulation. In subjectifying the facts of the Yugoslav Wars, she has succeeded, even if inadvertently, in giving Karadžić—an elderly, imprisoned man, shunned by the international community—a small victory against his many prosecutors.

The essential focus on him and her—their mutual psyches and their interrelation, and the possessive frame suggested in the title—is the root of this book’s imaginative limitations. Stern attempts to move beyond history without accepting that she needs first to understand it, since even the most fanciful or psychotic departures are derived from material reality.

The issue here is not that Stern sought to embrace “the perpetrator’s subjectivity” as her “process” in following Karadžić’s “moral logic,” as Stern has presented the misunderstanding over her book (and some of her earlier work). The essential question of understanding and perspective in genocide has produced valuable reflections. Primo Levi’s “Vanadium” finds the author working years after the war with one of the chemists who oversaw his captivity at Auschwitz. The German doctor hopes a personal meeting will be “useful” for them both. Levi feels “fear” at the prospect: “I know myself: I do not possess any polemical skill, my opponent distracts me, he interests me more as a man than an opponent, I take pains to listen and run the risk of believing him; indignation and the correct judgment return later. … It was best for me to stick to writing.”

Against the spirit of Levi, Stern became beholden to Karadžić’s perspective, and assumed that merely noticing it happening justified her methods. As Stern told Robert Wright in an interview, the fact that Karadžić disapproved of the book is what made her surprised that his opponents also disliked it.

The book opens with Karadžić, enemy of the United States, putting hands on Stern, a former Clinton administration official, in a small prison room. “You have to concentrate,” he tells her, “very much in control of himself” as he initiates the process of “bioenergetic healing” by rubbing her palms from the side, having moved to stand directly behind her as a guard stood watch. In this scene, Stern’s focus is on scanning her own sensations for information: “He was still looking at me, indicting me with his gaze. It came to me that he wanted me to sense his power, maybe to frighten me.” The 100-page dossier Stern’s students made for her before she first met Karadžić quickly showed its limits.

After Karadžić admonishes her concentration deficit, Stern has the “shame-inducing thought” that she was “stung” by “the first F of [her] life.” Used to being the “teacher, not the student,” now she was “like an obedient child, or a star student.” “Under Karadžić’s gaze,” she writes, “I regressed.” She entertains his hoary psychological drivel, learning of how Karadžić, who had talked his way into the Red Star Belgrade soccer team as a psychologist, told the players to lie down in the dark and imagine they were bees, “flying from flower to flower.” It was innovations like this in “psycho-training” that led Karadžić to claim he could make Red Star, the leading soccer team in Serbia, the “best team in the world.”

Stern’s personal mission to Karadžić is expressed in her scholastic dutifulness: Struggling to grapple with Karadžić as a whole construct, Stern parses his words. She notes that she doesn’t know what Karadžić’s term “metacommunications” means and appears haunted by the possibilities. She does follow up on a few claims that turn out to be lies, though—like his claim that his “mystical practices” were based on Kabbalah, or that he didn’t know about the killings at Srebrenica.

The meta-bizarreness of the enterprise sometimes becomes comical. “I was ready to believe everything he said until now,” Stern says of their first meeting. “But I found it hard to believe that he wouldn’t remember the exact number of lectures he had given during such an exciting sojourn, his first time in California.”

The psychodrama between author and subject constantly shapes this book’s perspective on events that shook and formed the lives of millions. Stern feels bound to him: “Both of us were locked up, working together on the project of my learning about him: we were fellow prisoners,” and becomes bound up in his cause. Stern calls Karadžić—a man who helped make his nation a global pariah—a “genius at establishing an alliance.” He earns that praise for a silly analogy that drew “a moral equivalency between Bosniaks and secessionist slaveholders, and between Serbs and abolitionists,” which worked “in this case with me as an American rather than as a Jew.”

As she gets closer to Karadžić, Stern’s yearning to emerge from the encounter having changed him grows: “The truth is, I didn’t want him to lie to me. I wanted, grandiosely, to be the one person to whom he would tell the truth.” (She later notes that she wants “to believe in the possibility of a transformation from bad to good, for all of us.”) As the dynamic appears to build, she goes out of her way to send him a collection of poems by Czesław Miłosz (“I couldn’t resist. … That was the first time I fell in. It lasted for a while”), which she had previously described to him. Karadžić, for his own part, tells Stern that she reminds him of his wife when they were young; Stern thinks he’s “sincerely expressing regret about his lost youth.”

In several widely circulated passages, Stern appears to describe attraction to her war criminal. While some of these are already infamously awkward (“My research assistant thought he looked a lot like Pierce Brosnan at that age”; “I remember the sensation of taking in his presence. Tall. Polite. That Hair. Striking features. Prominent bone structure”), they are not straightforward declarations, even if critics can easily label them as such. Stern seems to be trying to distance herself from Karadžić’s presence while drawing from it, as a literary device seeking out the role of sexual magnetism in political authority and violence.

Stern’s shame radar is strong, and its scope is wide. It encompasses the nuisance of a security check: “The removal of any jewellery, the sideways, stocking-footed walk of shame through the metal detector.” It feels wrong to her that she is partial to the “strange mournful sound” of the gusle folk instrument, as if it were permanently tainted by her encounter with Serbian nationalism. When she visits Karadžić’s place of birth in Montenegro, “it felt wrong, somehow, to enjoy the stark mountain light.” Speaking backwards in time to the deceased Ivo Andrić—a novelist of Balkan ethnocultural complexity whose statue in a Bosnian village was destroyed on the eve of the war by a Bosniak—she wishes to convey that “sometimes shame augments the transformation of fear into hate.”

Karadžić leaves Stern feeling “invaded” when he cold calls her at home or with her family. Contemplating her entanglement, Stern wonders whether the “shame [she] needed to be protected from was his or mine or both.” The passage is distressingly reminiscent of one from her memoir about her rapist: “That man penetrated me with his shame. Shame, I realize now, is an infectious disease.”

Karadžić seeks to build bridges with Stern as a Jew, achieving it with little effort; she treats generic, hammy pitches seriously. “Historic people like Jews and Serbs don’t think that historical figures lived in a different time from our own,” he puts forth. “Historic peoples believe in the existence of eternity.” Stern says she has “no idea what he meant” by this, but that she “did notice he was finding a way to link Serbs and Jews again.”

“It’s interesting: As a Jew,” she told Wright, “I always find it surprising that any nationalist would think that it makes sense to cozy up to Jews in any way. But it turns out that … Bosniaks also see themselves as Jews. There’s no question that Bosniaks were massively more victimized than Serbs—but yet Serbs wanted to think of themselves, and present themselves as the victim, as the Jew, in that situation.”

Stern states that her “impossible task involved the effort to stay open to Karadžić’s explication of why he behaved as he did, rather than blindly accepting the common narrative—that the Serbs were evil genocidaires and the Muslims guileless victims.” The essential problem of the book, as far as its treatment of the historical events is concerned, is shown in her considering this to be its task, and these her limitations. There’s a helpless sadness, as a reader, in having to accept Stern’s voluntary belief that in writing this book she would “have to surrender to Karadžić’s idea of himself.” Guided by Karadžić and therefore his historical subjectifications, she elevates the lies, delusions, and fragments of Serbian nationalist revisionism.

The crossed wires of shame transfer into her analysis of the Bosniak political approach to security, statehood, and intervention. “Other SDA [the Bosniak political party seeking independence] leaders also admitted that they had actively lobbied the West to recognize Bosnia’s independence in the expectation of help,” she writes in a revealing passage. Note Stern’s usage of “admitted”; “actively” (would “passively” crying out come with less shame?); “expectation of help,” as if the whole global system of states isn’t based on seeking recognition.

Stern notes that “later it would become clear that Sarajevo’s Muslims were being shot at—not only by Serbian snipers, but also occasionally by their own leadership.” But as historian Marko Attila Hoare noted on Twitter, a closer examination of the proportionately tiny section (pp. 1,821-8) from the ICTY proceedings to which she herself alludes makes it clear that presenting these negligible occurrences in the way Stern has is a grotesque distortion of the real events in the context of this passage. Thus, moments of empirical clarity (“It is important to note that of the civilians killed during the war, the vast majority were Muslim”) alternate with relativistic diversions repeatedly.

“Like many people who work on national-security issues,” she writes in an unconsciously partisan book, clouded by its own misdirected quest to transcend partisanship, “I’m not especially partisan.” Stern seeks refuge in convenient generalities: “One discovers, over time, that today’s evil perpetrators were yesterday’s guileless victims—just as is often true in ordinary life. A victimization Olympics comes into play, and the noble-minded humanitarian observers finds herself in a moral muddle, wanting to be objective and fair to all sides.”

One contribution that was, in its own sick way, fair to all sides, was Karadžić’s 1991 speech in the Bosnian parliament, in which he announced the inevitability of the Bosnian Muslim genocide. (Essayist Aleksandar Hemon, who saw the speech live on television, later reflected: “What I didn’t see then is clear to me now: the possibility of war not happening was already completely foreclosed.”) Karadžić tells Stern the speech “was a warning, not a threat.” “In my view,” writes Stern, “it was both.”

When is a threat not also a warning—when part of you might not mean it? With this subtle move, Stern points to Bosniak political agency (a warning is something you are free to respond to) and leaves the door open for Karadžić to find his place in a psychic rather than political narrative. Even after declaring his intention to commit genocide, actually committing it, and gaining additional notoriety after being sentenced for it, Karadžić is still spreading uncertainty about his motives, actions, and significance.

In the summer of 1992, the year Stern completed her doctorate at Harvard, which she notes was on “chemical weapons,” focusing “mainly on the mechanics of violence, with little attention to the human toll,” British-Polish filmmaker Pawel Pawlikowski was witnessing the collapse of Yugoslavia.

His 1992 documentary Serbian Epics is a mesmerizing account of the delirium of Serbian nationalism during the war. Pawlikowski, a British-Polish director who discovered later in life that he was descended from a Jewish woman who died in Auschwitz, captures how the fuel of history gave life to Karadžić’s killers.

In a room with flickering electricity, Karadžić and Ratko Mladić, leader of the Bosnian Serb army, plot the genocide over coffee and spirits, cigarette smoke rising in the competitive tension between them. Karadžić draws new borders on a map, intending, of course, to make the actual terrain around him yield to his clear new lines. “It’s not right,” he states, “that Croatia should have all the coast, and we have none.”

Pawlikowski then documents Karadžić roaming the terrain above Sarajevo to a soundtrack of gusle tributes to Serbian heroism. He informs his soldiers that the era of “domination by Muslims of Serbs” is now over. He’s on a military phone to his wife when someone asks him what breed of dog he’s petting: “Serb.” Speaking to visiting Russian writer Eduard Limonov, he says that the people his men are shelling are merely ethnic Serbs who selfishly converted to Islam and shuns them as “successors” of the centurieslong Turkish occupation. He tells Limonov with a chuckle that he scares himself sometimes contemplating the predictive violence of verses he wrote in his youth. Stern describes her repeated viewing of Pawlikowski’s film as a “confession”: “I find the chanting of the epic poems irresistibly compelling.”

One shot first focuses on Karadžić from behind, waving his arm across Sarajevo as he describes his plans to restore Serbian ownership over it to Limonov, before the camera’s focus changes to the battered cityscape. It is a stunning evocation of the way genocide collapses the separation between the subjective and the objective.