The Jewish People’s School of Montreal

A memoir of one of North America’s first and most enduring day schools, and where those kids ended up

When I was a child, I attended one of North America’s first and most enduring Jewish day schools, the Jewish People’s School of Montreal, affectionately and colloquially known as the Folks Shule (the people’s school). The Jewish People’s School was the product of Jewish reaction to the unique cultural and historical circumstances of the city in which it was founded. Montreal at the beginning of the 20th century was the largest city in Canada and one that was divided between two religious and linguistic groups, who were not particularly friendly to each other: French Canadians who were primarily Catholic, and English Canadians who were primarily Protestant.

In the early 20th century, Jews made up the largest non-Christian minority in the province of Quebec. As the century progressed, their numbers kept rising in response to economic hardship and persecutions in Europe, especially the Holocaust. This meant that until 1976, when the separatist Parti Québécois came to power, fueling a mass exodus of Montreal Jews to Toronto, Montreal had the largest Jewish community in Canada, and Yiddish was the third most commonly spoken language in the city after French and English.

There were no nondenominational public schools in Montreal when I was a child, at least not in the way Americans understand public schools as being open to all, regardless of religion or ethnicity. Like the population itself, the schools were divided into French Catholic and English Protestant and run by two separate school boards. (To further complicate matters there were also French Protestant and English Catholic schools.) Since the Catholic school board wanted nothing to do with Jews, Jewish students, for purposes of education, were designated as Protestants and sent to the Protestant schools, where instruction was in English, thereby ensuring that my generation of Jews would grow up primarily English-speaking. Jewish students who attended these Protestant schools began the school day by reciting “The Lord’s Prayer”; they sang “Onward Christian Soldiers” and took part in Christmas pageants. In my one year at a Protestant public high school, the year after I graduated from Jewish People’s School, we recited the Lord’s Prayer in both English and French every morning, despite the fact that the student body was 97% Jewish. I can still recite it in either language.

We Jews were guests in the Protestant schools, put there on sufferance, tolerated but not loved. In the early decades of the 20th century, Jews could not even teach in these schools, they could not be administrators, nor sit on the school board. These restrictions gradually eased as the century wore on, but they explain why the early leaders of the Montreal Jewish community felt it necessary to establish their own separate schools.

But if the schools were founded as a response to exclusion from the outside, they were also an expression of ideological motivations from within. Crucially, one of these ideological motivations had to do with the preservation of Yiddish. By placing Yiddish at the center of their curriculums, the Jewish People’s School and the Peretz School—the two earliest of Montreal’s Jewish day schools—fostered a long-term commitment to the language in the community and ensured the survival of Yiddish in Montreal long after it had disappeared as a lingua franca for Jews in other parts of North America.

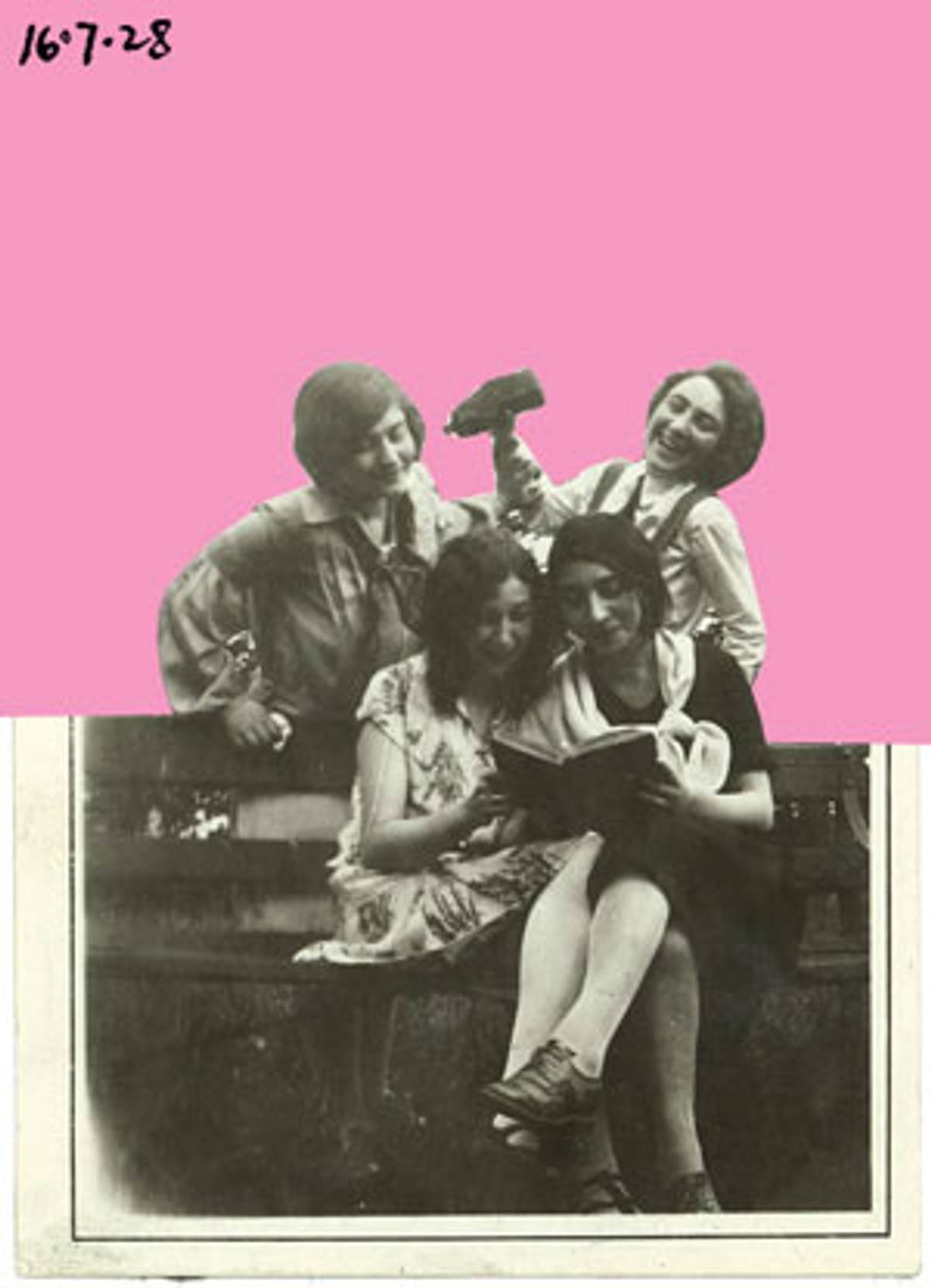

In 1928 the Jewish People’s School became the first all-Jewish day school in Montreal. The ideology of the school was secular and Zionist. By the time I attended in the 1950s, the curriculum for the most part followed that of the Protestant school board, teaching arithmetic, reading, composition, and Canadian history in English. But these courses were crammed into half a day, while the other half was devoted to the study of Jewish subjects, including language instruction in Yiddish and Hebrew, Chumash (taught in Hebrew), Yiddish literature (taught in Yiddish), and Jewish history. Although originally ideologically distinct—the Peretz Shule was more Yiddishist and socialist, the Folks Shule more Zionist and slightly more religious—monetary constraints led the two schools to merge in 1971, so that today the school’s official title is the Jewish People’s and Peretz School (JPPS). A year later they also added a high school named after the Hebrew-Yiddish poet, Chaim Nachman Bialik.

It still amazes me that as children we were expected to learn four languages: Yiddish, Hebrew, English, and French. When my class had a reunion in 2013, one of my former classmates brought the scrapbook that we had compiled for her when her mother’s remarriage forced her to leave Montreal for New York. At the age of 10, we had all written farewell letters and poems to her in English, but we were also required to write another letter in either Yiddish or Hebrew. Most of us wrote in Yiddish, although a few chose Hebrew. It was startling to see how fluent we were in these non-English languages. And what was even more startling to me was how poorly I wrote English when I was 10. My Yiddish letter to my friend was far more eloquent and fluent than my English one. Today, sadly, the reverse is true.

***

I was not particularly happy at this school as a child. My schooling, especially my Jewish schooling, had been a cause of friction between my parents.

Both of my parents were Holocaust survivors who landed in Montreal several months before my birth. Yiddish was the language of my home; English would be the language I learned at school. My father was intent on assimilation—the sooner the better—into the broader culture of Canada. He wanted to forget the past and become a full-blown multilingual Canadian. Despite the fact that I am named in remembrance of my father’s mother, who was murdered at Auschwitz, he insisted on Anglicizing my name, which my birth certificate lists as Goldie and not Golde like my grandmother’s. My father was a Bundist, a socialist, who prided himself on his universalism. A Jewish education was too parochial for his taste. He had also internalized the many years of persecution he had endured in his native Poland and was convinced that a Jewish education would be inferior to anything that was available in the “normal” schools of Montreal. He wanted his children to be accepted and accepting, to be tolerant of the whole world. In my father’s mind anything to do with Jewish tradition went against these ideals.

My mother, on the other hand, was a Yiddish writer who defined herself first and foremost as Jewish, a self-definition that was only strengthened by her experiences during the Holocaust. For her, as for all writers, language was more than just a means of communication—it was the sine qua non of aesthetic expression and literary creativity; it was what defined her to the world and to herself. She could no more abandon Yiddish than she could cut out her own tongue. Yiddish was the means by which she tried to tame the terrifying demons of the past by writing her magnum opus, The Tree of Life—a re-creation in fiction of her experiences during 4 1/2 years of incarceration in the Lodz ghetto. She very much wanted her children to learn Yiddish and to have a Jewish cultural education similar to the one she had had in Poland, where both she and my father had been students at the Yiddish-language Medem School.

Not surprisingly, given their different approaches to dealing with the trauma of the past, my parents could not agree on the status that Yiddish should have in our home. When I was very young my father spoke Yiddish at home, because it was his mother tongue and the language he used to communicate with my mother, my grandmother, my aunt, and all the other members of the Yiddish-speaking Montreal Jewish community. But it was not long before he switched to English and decreed that the language of our home should henceforth be English. He himself stopped speaking Yiddish altogether.

I was the firstborn child, so from the time I was young the issue of my schooling was a matter of intense discussion. My father insisted that I learn English and taught me haphazardly at home. My mother insisted that I expand my knowledge of Yiddish and Yiddishkeit by instruction in a Jewish school. My father was convinced that the Montreal Jewish schools were sectarian and inferior. My mother insisted that I be sent to one of them. In this argument, my mother initially prevailed and, despite the cost, I was sent to the Jewish People’s School. But when my brother was born, several years later, my father insisted that his son was going to a “real” school. We were more prosperous by then, and so my brother was packed off to a nondenominational private school in Westmount, the wealthiest suburb of Montreal, where instruction was in English and there were no Jewish subjects, although many of the students at this school, too, were Jewish. Today my brother cannot speak or read Yiddish; he can only read his mother’s work in translation.

As for me, the pedagogical arguments between my parents made for a divided loyalty to the school. I was aware of my father’s hostility to all things Jewish. I never mastered Hebrew, much to my regret, because this language in particular was the object of my father’s scorn as “useless” in a Canadian context. And I developed an inability to read fluently out loud in Yiddish. When asked to read a passage in class, I stumbled over each word, even though I knew the language well and had no trouble understanding what I was reading. It was my way of acknowledging my father’s resistance as well as fulfilling my mother’s wish. To this day, I am reluctant to speak Yiddish in public for fear of stumbling over the words.

Ironically, the Jewish school in which Yiddish formed such a large part of the curriculum instilled in me a craving to master English. I was ashamed of my mispronunciation of English words, ashamed of my Yiddish accent, which the other children made fun of, ashamed of the many spelling and grammatical mistakes in my English compositions that were red-penciled by my English teachers like so many lashes of a whip. I wanted nothing better than to succeed in English. I may have been a student in a Jewish school, but I emerged from that school an Anglophile.

It was only later in life that I became aware of how much my passion for English had cost me, especially when it came to Yiddish. Not only had my knowledge of Yiddish grown rusty by my late adolescence, but my vocabulary had remained that of the 12-year-old I was when I graduated from the Folks Shule. When I was in my early 20s and a graduate student at Columbia University, I decided to do something about this and took the first steps toward recovering Yiddish by attending a course taught by Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett—another Canadian—on East European Jewish folklore. I also got a job teaching Yiddish in the adult education program at New York University and this helped to reestablish and enhance my knowledge of the language. Sometimes the best way to master a language is to be required to teach it.

My attitude toward the Folks Shule also changed dramatically and the older I got the more grateful I became to the school to which I owe my Jewish education and my sense of myself as a Jew in a non-Jewish world. It is because of this school and its teachers that I have always defined myself first and foremost as Jewish. And it is thanks to this school that I see no discrepancy between being Jewish and being nonreligious.

***

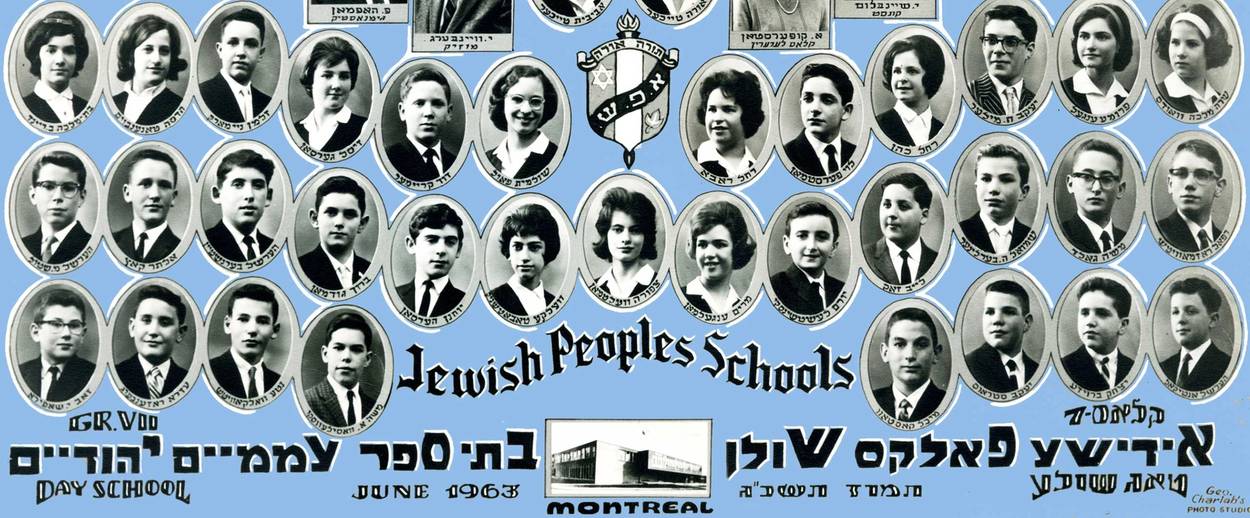

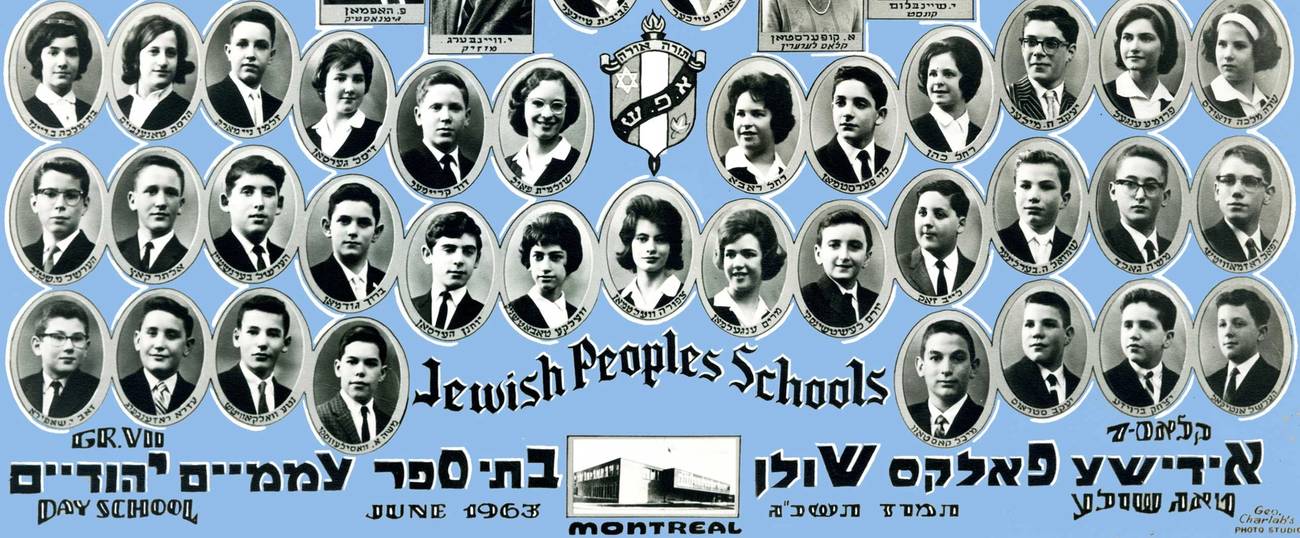

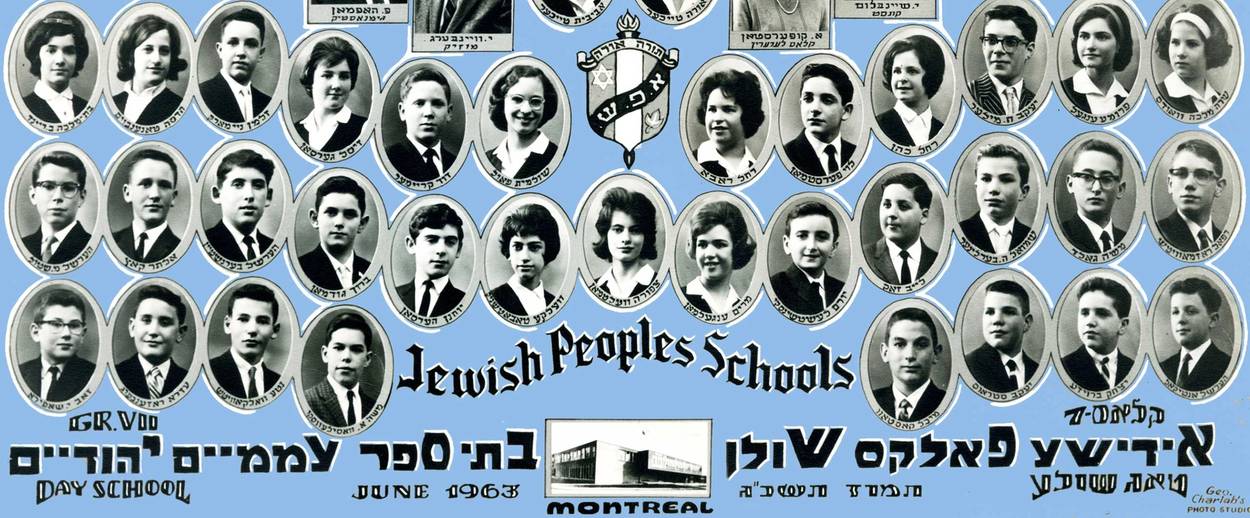

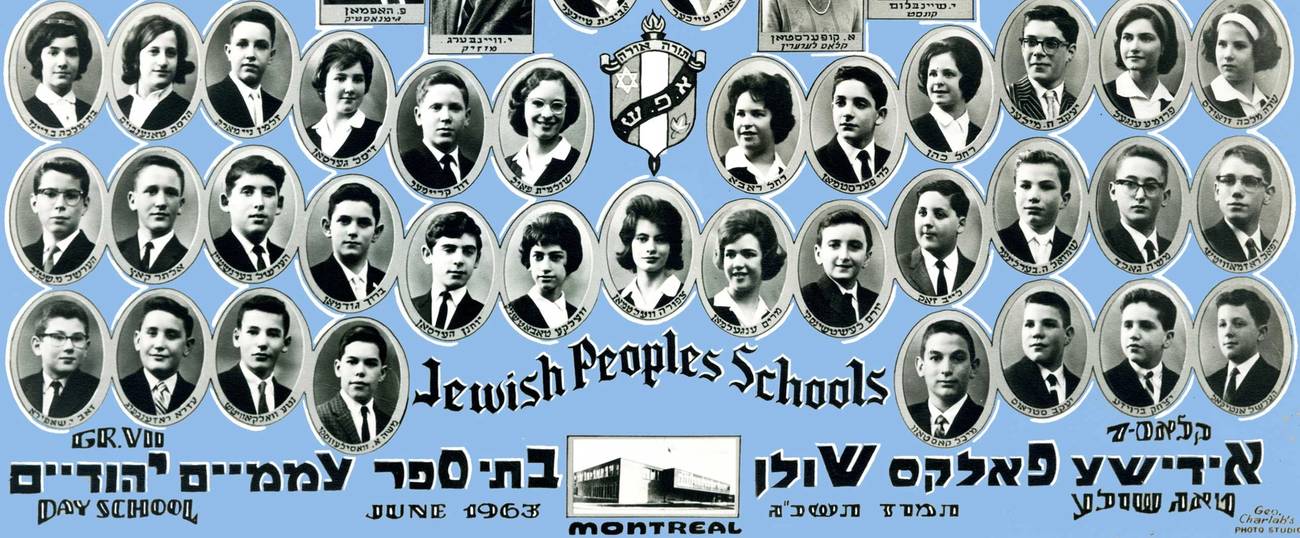

In July 2013 my Folks Shule graduating class held its 50th reunion. When we last saw each other, we were all 12 or 13 years old; in 2013 we were all in our mid-60s. A lifetime had passed. We were no longer children, but rather the same age as our grandparents had been when we were at school; and yet, this school shaped us in quite profound ways despite the fact that we graduated from it so long ago.

My Folks Shule classmates and I were buffeted by the winds of history, especially Jewish history, although as children we could not know this. We started kindergarten scarcely 10 years after the end of World War II. Several of my classmates were the children of parents who had survived the death camps of Europe, or who had been in hiding during the war. Thus, for a substantial number of us, Yiddish was the language of our home and English the language we learned at school. After the Hungarian revolution of 1956, we had a new cohort of classmates whose parents had fled Hungary in the wake of the revolution.

The Holocaust hung over my early schooling as an event both subliminal and omnipresent. Some of our teachers, those who taught Yiddish and Hebrew, were also Holocaust survivors. Some recounted anecdotes of their experiences during the war, but I don’t remember this happening very often. Perhaps I didn’t notice because I heard so much about the Holocaust at home. Still, I think our teachers were aware that we were too young and could not stomach too much horror. 1950s Montreal was home to a large contingent of Holocaust survivors and I believe that we were all more or less aware of what had happened, even when it was not spoken of openly. Once, when I was sick, my Yiddish teacher paid a visit, ostensibly to see how I was doing, but really to talk to my mother. I overheard them discussing their experiences during the war and debating how much of that experience should be conveyed to children. Another time we were handed out small packets of plastic dreidels and Hanukkah gelt to play with for Hanukkah. Almost immediately we were asked to return these, because someone noticed that they had been manufactured in Germany. Anything to do with Germany was anathema.

The school’s animating philosophy was Zionism. We were infused with an appreciation for the heroism of the early settlers of the State of Israel; we sang songs in praise of the bravery and industry of the chalutzim. We collected money for Histadrut and for planting trees in Israel. We knew that the Israelis had made the desert bloom. I had no doubt as a child that Zionism, a country of our own, was the best possible answer to the endless persecution that Jews had endured throughout their history. I still believe this.

Ironically, this Zionist Montreal school achieved a better symbiosis between Yiddish and Hebrew than existed in Israel, where in the early years of the state, anti-Yiddish sentiment had resulted in riots. In our Jewish school in Montreal, Yiddish culture coexisted with Hebrew culture without strain or contradiction. I remember once at assembly we were addressed in Yiddish by Israel Joshua Singer, the author of The Brothers Ashkenazi and elder brother of Isaac Bashevis. Dora Wasserman, the founder of the Yiddish Theatre of Montreal, was a frequent visitor to the school, where she staged plays for us in Yiddish.

The Jewish school was like a cocoon in which the larger non-Jewish world barely existed. It was something of a shock to graduate and go out into a world where Jews were often an unknown quantity; where we were, at best, objects of curiosity; at worst, subjected to stereotyping and the occasional unfriendly remark. My first name, for instance, elicited puzzled queries among my non-Jewish classmates. Was it short for Goldwyn? Was it a nickname? Was I named after a fish? To this day, I am brought up short by how little many non-Jews, even the friendliest, know about Jews.

What had we done with our lives? Were we happy with the way they had turned out? Did our experience at the Jewish school have an impact on us?

This sense of having lived in a privileged Jewish space while at Jewish People’s School was mentioned by several of my former classmates in the biographical essays that we wrote ahead of our reunion. Also mentioned were the larger political and cultural currents that affected our lives after we left the school. One of my former classmates wrote of the difficulties she had accepting that her adult daughter had become ultra-Orthodox. Another regretted that her children had married non-Jews.

All kinds of questions hung in the air, given how much time had passed since our graduation in 1963 and our meeting again 50 years later. Whole lifetimes had gone by while we lived parallel lives largely unknown to one another. We were the baby boom generation that came of age in the 1960s. Several of us admitted to having the “wild” youths that were typical of the ’60s. We all made careers, marriages, divorces—and there had already been a few deaths. A good many in the class were retired. What had we done with our lives? Were we happy with the way they had turned out? Did our experience at the Jewish school have an impact on us?

Most of the 30-odd people who submitted their bios would answer these questions in the affirmative. Many of us were still involved in Jewish community affairs. Several sent their own children to Jewish schools, some even to the Folks Shule. For most of us, clearly, English is our primary language. I would guess that very few in my graduating class of 61 students can still speak Yiddish, and I doubt that more than a handful of us are fluent in Hebrew. But no one regretted being exposed to multiple languages at an early age.

We were the generation of Montreal Jews that had to deal with the aftereffects of the nationalist Parti Québécois coming to power in 1976 that sent many Jewish Montrealers to Toronto and other points west and south. While none of the bios specifically mentioned the turmoil unleashed by the Quebec independence movement as a reason for leaving the province, the fact remains that the majority of my former classmates now live in Toronto or in the United States. Only three live in Israel, an interesting statistic, given that our school was so strongly Zionist in orientation. Of my former classmates who have remained in Montreal, each one begins his or her biography by saying, “I must be the only one still living in Montreal.” In fact, the Montreal contingent was larger than one might expect, given the fear in the Jewish community when French Canadian nationalism became a political force in Quebec.

Those of my classmates who submitted their biographies were clearly content with their lives. Several commented that “it’s been a good life.” This is not surprising, since those who have done well are the most likely to come to a school reunion. Most are now grandparents. Indeed two were prevented from attending the reunion by the imminent arrival of a grandchild. Of those who are retired, the jobs they have left are all white-collar. Several went into law, several into business, many into education and social work. A few of us became university professors, one became a doctor, one a painter based in Israel, one owns a company that supplies special effects to Hollywood movies, one is a former Montreal city councilor, one was a news writer for the major Canadian television networks, one is a world-renowned scientist now based in England. I would have expected more medical doctors, but other than that, I believe we conform to the normal Jewish demographic of chosen professions. Most of my classmates have university degrees, the vast majority—not surprisingly—from McGill.

Many more women than men attended the reunion, even though the ratio of girls to boys in the original class had been almost equal, with girls outnumbering boys, but not by much. (There were 33 girls in my 1963 graduating class and 28 boys.) In another sign of the great changes my generation has lived through, several of the women commented that they were the first women in their law firms, or the first women to be hired by their businesses. All the women who submitted their bios had careers.

Sadly, the Jewish secular schools of Montreal are in trouble. When I was a student there, the Jewish People’s School was in its heyday. Our teachers were people of learning and stature in the Jewish community, such as the school’s principal, Shloyme Wiseman, a respected pedagogue, and its vice principal, the Hebraic scholar Shimson Dunksy. They passed on their love of learning to the next generation of Jewish scholars: Ruth Wisse and David Roskies are alumni of the school. But by the time of our reunion in 2013, enrollment was down and the school was struggling to stem the tide of parents preferring to send their children to public schools in Montreal, where the schools are now divided along linguistic rather than religious lines.

Yet the school was also its own worst enemy. The two organizers of my class reunion met with indifference when they approached the Jewish People’s School with the idea of hosting our reunion. Not only was the school unwilling to capitalize on what would have been great publicity for them, agreeing only to keep the building open on a Sunday so that we might walk through it again, but they were remarkably uninterested in collecting on the financial donation that we voted to contribute in the name of the class of 1963. The lack of interest in supporting students from the past did not augur well for the future, and, sure enough, declining enrollments caused the school in 2016 to sell the building that housed its elementary school and consolidate the elementary and high school divisions in one building in Côte Saint-Luc, one of the most Jewish suburbs of Montreal.

I look back with great affection on the Folks Shule, because it knew me before I knew myself, and shaped so much of what I am today. Whenever I translate from Yiddish into English, whenever I read Peretz, visit Israel, or go to a Jewish play I pay tribute to the education I received there. What more can be said of any school?

Goldie Morgentaler is the translator and editor of Chava Rosenfarb’s collection of short stories, In the Land of the Postscript: The Complete Short Stories of Chava Rosenfarb, published by White Goat Press.