Smuggling Jewish Refugees in Key West

How the Caribbean became a stopping point for the American journey of so many Jews

Although smuggling in the Florida Keys in the first half of the 20th century was an open secret, discovering what people did illegally a hundred years ago poses significant challenges. Legitimate aid organizations like Joseph Steinberg’s Centro Maccabeo, and the Industrial Removal Office a generation earlier, left behind voluminous documentation that makes it possible to recreate the flow of migrants and identify the people involved. With the smugglers, much of what we know comes from the Bureau of Investigation reports describing the attempts that were intercepted. None of the smugglers or migrants who came through Key West is still alive to tell their side of the story. Very few of them talked about it when they were alive. “Open” or not, most of the smugglers’ secrets were carried to the grave.

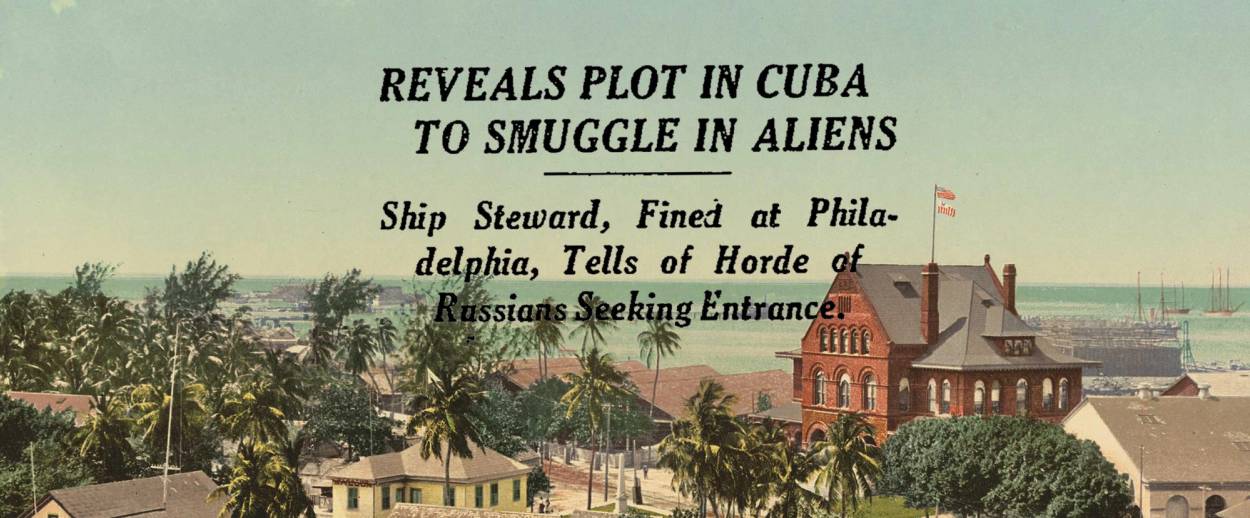

Some of the most specific allegations about Jewish smuggling in Key West came from a member of the Ku Klux Klan who was acting as an informant to the U.S. attorney general. Although it is rarely discussed today, the klan was active in Key West during the 1920s. The violent, racially motivated murder of Manolo Cabeza in 1921, which followed a cross burning on Duval Street and his public abduction and assault, showed that robed and hooded members of the KKK would stop at nothing short of murder to enforce their white supremacist ideal. It also demonstrated how profoundly Key West had changed since the 1890s, when José Martí rallied Jews and others to a colorblind ideal and citizens elected a black man to the sheriff’s office. Local complicity in klan activity explains why the identities of Key West klansmen were kept a mystery until 2012, when an anonymous donor presented the Monroe County Public Library with a startling document. The original 1921 charter of Florida’s klan No. 42, the klan of the Keys, reveals that the Key West klan was in fact founded by some of the island’s most prominent citizens. And it suggests that anti-Semitism was at work in Key West in pernicious ways during the 1920s.

Heading the local klan organization was Exalted Cyclops Joseph Yates Porter, who had a documented history of anti-Semitic behavior. It was Porter, as state health officer, who had complained of the “foreign element” of the Jewish peddlers during the yellow fever epidemic 30 years earlier, while his deputy had slandered Jews as being “naturally suspicious and skeptical.” Second in command was J. Vining Harris, who was positioned to do serious harm to Jewish interests and potentially put local Jewish smugglers behind bars. Harris was an attorney and former Navy intelligence officer, and in 1922 he voluntarily became an informant to the U.S. attorney general, Harry M. Daugherty. Harris filed a report to Daugherty that year with an explosive allegation: Rabbi Lazarus Schulsinger, the chief religious official at Key West’s Congregation B’nai Zion, was part of a vast international conspiracy to smuggle Jewish illegal aliens from Cuba to Key West.

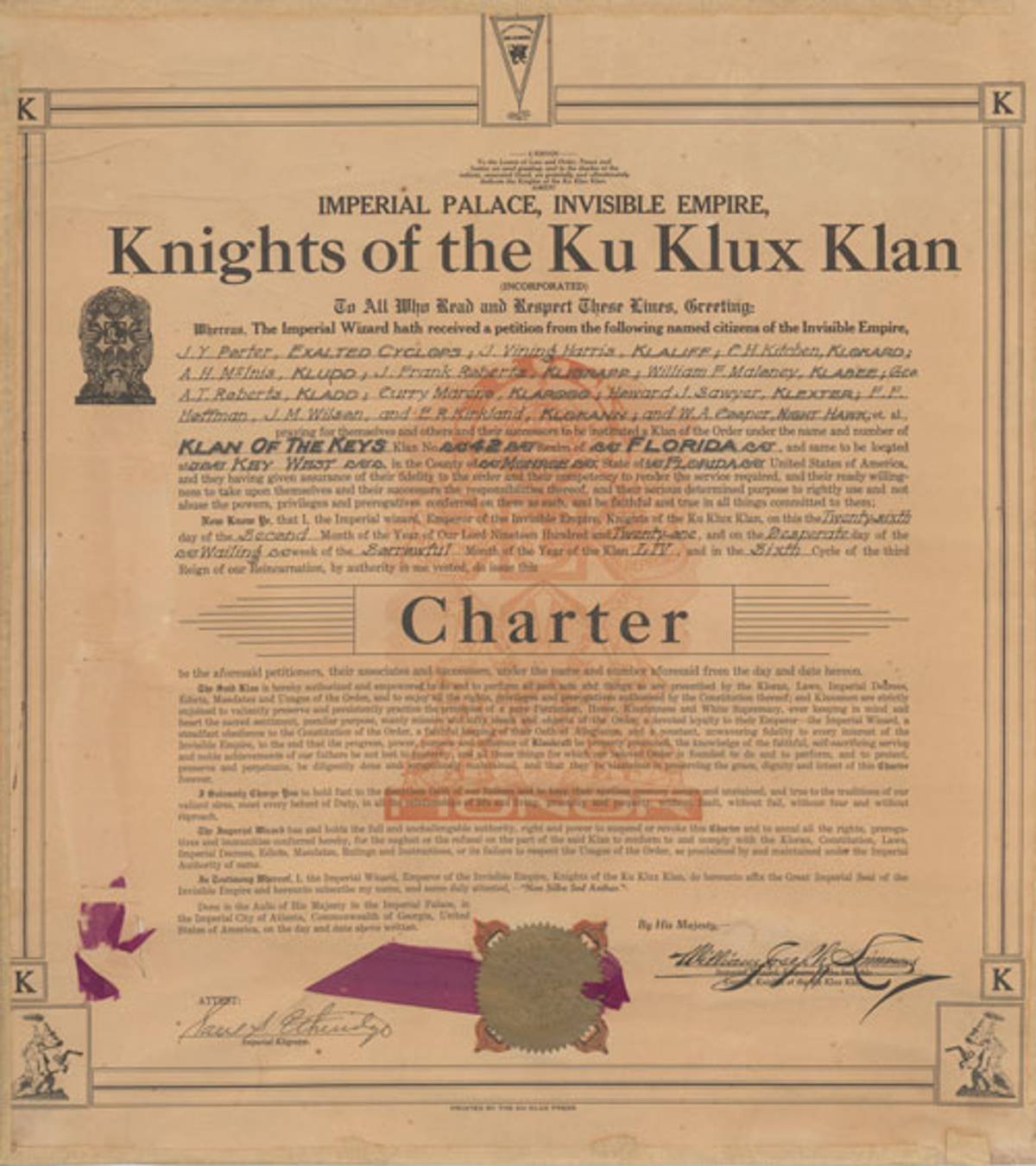

According to Harris, Rabbi Schulsinger’s smuggling operation delivered illegal Jewish and Chinese migrants into Key West with the support of a shadowy trio based in Havana. The Cuban group was made up of “a Jew by the name of ‘Fox,’” “a German by the name of Hans Huspal but better known in Havana as ‘Hans Rosebaum,’” and a Hungarian named Goerlich. In Key West, the rabbi’s network had even infiltrated the Custom House, where chief immigration inspector George Schmucker was an important accomplice.

Smugglers working with Schulsinger had two main ways of getting Jewish aliens to Key West. The first technique employed local captains like De Castro and Cabañas, who smuggled groups as large as 40 people at a time across the Florida Straits during the middle of the night. For the majority of the voyage, migrants were confined to the small cabin spaces of private motorboats like Cabañas’ Edelmiro or Orien Demeritt’s Marenostru. Then, as they approached Key West, smugglers set the weary migrants ashore on one of the hundreds of uninhabited islands in the Keys backcountry. From here, a smaller boat would pick them up and deliver them back to Key West in smaller groups. At this point, accomplices like Abraham Leibovit would take the migrants in and provide them with lodging and food while arranging for travel to their final destination.

Rabbi Schulsinger’s second technique provided an alternative to this dangerous route and was particularly well suited to women and children who hoped to avoid the dangers of an ocean crossing. Exploiting the fact that women were rarely issued the immigration or citizenship documents that men were required to carry, alien women and children boarded daily passenger steamships like the Mascotte in Cuba, escorted by American citizens posing as their husbands and fathers, and traveled to Key West in broad daylight. Schulsinger’s sophisticated network also included counterfeiters who produced fake passport and visa documents, and costume artists who disguised the migrants with hair bleach and other tricks. And their payroll included shipping company officials in Havana, who had agreed to look the other way while Jewish aliens boarded commercial ferries bound for Key West.

Months before Harris’ letter, Rabbi Schulsinger had nearly been exposed. He had arrived in Key West from Cuba aboard the Mascotte with Morris Tennenbaum and four other Jews in May of 1922. The passports carried by the others attracted suspicion from immigration officers, who held them several hours for further questioning. While they waited, telegrams from consular agents in Cuba shared the “very disquieting rumors” that Morris Tennenbaum was deeply involved in smuggling rings and the mastermind behind the widespread forgeries of visas and passports used by Jewish migrants. As a known figure in Key West, Schulsinger avoided suspicion that day. But in a report that he filed to Director William J. Burns of the Bureau of Investigation, Special Inspector William Peters confirmed that Rabbi Schulsinger was “implicated in these irregularities.”

Jewish aliens or their families paid anywhere from $50 for a trip across the Florida Straits to $1,000 (worth about $14,000 in 2017) for safe passage all the way from Europe to their final destination in the United States. According to Harris, Schulsinger handled the money side of the operation, collecting payment directly from the families of migrants, and delivering the funds to his co-conspirators in Cuba. He may have coordinated these activities with David Aronovitz, another prominent Key West Jew who was named by an informant in Miami as an agent for Romanian Jews seeking access to the United States. (Ironically, the Key West federal courthouse where many smuggling cases are tried today is named for Aronovitz’s nephew, Sidney Aronovitz, who later became a prominent federal judge.) During the peak of the refugee crisis in Cuba in 1921 and 1922, Schulsinger traveled back and forth between Key West and Cuba at least once a month to deliver cash and provide other assistance.

Although no charges were ever filed against the rabbi, Harris’ allegations to the attorney general appear to have ended his involvement in the smuggling conspiracy. Schulsinger made only one visit to Cuba after Harris’ report, and he never again resumed his regular monthly schedule.

Luckily for the migrants, Schulsinger’s network had been just one of many, and Jews who were willing to enter the country illegally had numerous options. Refugees in Cuba could visit the official-seeming “Alien Information Bureau,” headed by a Hungarian named Isaac Weinstein, or a similar operation run by Romanian Jews, and easily purchase counterfeit passports and visas. Key West native Jack Einhorn recalls that Jewish families were smuggled by ship inside of railway containers filled with Cuban pineapples and bound for points north via the Overseas Railroad. In perhaps the most unusual smuggling attempt, 13 employees of the Johnny Jones Carnival Co. were arrested in 1928 after a group of Russian, Romanian, and Hungarian aliens was discovered hiding in the traveling carnival’s show cars during a stop in Key West.

Whether or not he continued to be involved in smuggling operations, Rabbi Schulsinger remained sympathetic to the plight of Jewish migrants. According to Einhorn and Milton Appel, another Key West native, a group was intercepted by immigration authorities around 1929 and held in Key West for several weeks. Rabbi Schulsinger and his wife, Ida, made regular visits to the migrants during their incarceration, delivering them kosher food and lobbying the authorities on their behalf.

The ultimate destination for most of the migrants was not Key West. They were trying to get to Chicago, or New York, or some other place where they had family. But you couldn’t easily put 40 migrants on a train car all at once without arousing suspicion, so they often remained at safe houses in Key West for several days or weeks. Here, the local community looked after them and helped make arrangements for the final leg of their voyage.

Evidence that would definitively identify the safe houses used by smugglers here is difficult to come by, but there are a number of likely possibilities. Abraham Leibovit’s property at the corner of William and Southard streets, where he and his family lived and ran a grocery store during the years when he was active in the smuggling operation, was probably used to house migrants as they waited to travel to their final destination. Rabbi Schulsinger’s house on Simonton Street, next door to the old synagogue, where Sarabeth’s restaurant is today, is another strong possibility, as is the large home at 626 William St., where prior rabbis had lived. These three locations are all within one or two blocks of each other, which would have made it relatively easy to coordinate movement from house to house.

One of the most intriguing potential safe houses belonged to Frank Lewinsky, who grew up in the family bar business along with his cousin Herman Wolkowsky, the bumboat captain, and who had flouted temperance laws in 1913. Less than a year after the passage of Prohibition, Lewinsky built a brand new building where his Duval Street saloon had been. To passersby it looked like Lewinsky had left the liquor business for the clothing store he ran there in subsequent years. A more curious passerby might have noticed that the saloon could have easily been converted into a clothing store at much lower expense, and that Lewinsky was taking a major risk in constructing a new building so soon after Prohibition had outlawed the one business he’d always known.

When Lewinsky’s descendants sold this building in 2013, contractors made an amazing discovery. A large underground chamber, sealed off since Lewinsky’s death, lay beneath the footprint of the building. Basements are rare in Key West, and the entrances to this one were completely hidden. The family had no idea it was there. Extending to nearly the edges of the building, the 6-foot-high room provides enough clearance for a person of average height to move around comfortably. There’s no surviving evidence of what it was used for, but it would have been an ideal place to hide bootleg alcohol, for example, or to run a speakeasy, or to provide a safe house for Jewish migrants who had recently arrived by boat from Cuba. A similar chamber was discovered around the same time right across the street. This room lay beneath the former grocery store of Jim Lee, a Chinese immigrant whose business partner Wing Lee had been implicated in the East Asia Company investigation at Willie Fung’s laundry.

Stories are told in Key West about underground tunnels that were used by Cuban rebels to hide weapons during the 1890s and by rumrunners to store bootleg alcohol in the 1920s. Allegedly, these tunnels connected a number of addresses in the vicinity of Solares Hill, the limestone outcrop that forms Key West’s highest ground at roughly 16 feet above sea level, where a natural cavern and freshwater spring had existed prior to development of the area in the middle of the 19th century. Prominent revolutionary Cubans and known smugglers had occupied some of these addresses, and it is thought that the tunnels enabled the secret movement and transportation of contraband from one conspirator’s house to another. This would have allowed smugglers to consolidate their cargoes in a hidden underground location while minimizing the amount of surface-level activity at any one street address. Oral histories describe a particularly well-constructed tunnel network that existed underneath the Weintraub Grocery Store, operated by Berman and Rose Weintraub, Romanian Jews whose wedding had taken place at the headquarters of the Cuban Revolutionary Party in the 1890s. Some say tunnels ran as far as three blocks north to Eaton Street, to the address where a Chinese alien named Wing Lung operated another laundry.

Firsthand evidence of these tunnels has yet to be documented. But tunnels similar to what have been described in Key West were recently unearthed in the town of Moose Jaw, Canada, and it has been found that they were used to hide Chinese migrants who were barred from legal immigration. One theory about Key West’s tunnels is that Berman Weintraub was familiar with the network through his connections with Cuban rebels during the 1890s, and that he decided to purchase this building, just one block from the home of the Cabañas family of smugglers, partly in order to control access to the tunnels that lay beneath it. It seems incredible, yet entirely possible, that Abraham Leibovit’s description of a “Jewish underground” in Key West was more than a figure of speech, and that these tunnels were used as part of the elaborate operations to rescue and resettle Jewish migrants.

The 1920s and 1930s were difficult for Key West’s Jewish community, but Jews in Key West knew how fortunate they were. Many were the first members of their family born in the United States or had themselves been born in Europe, where, as the 1930s ended, Hitler had solidified Nazi control over Germany and begun implementing his Final Solution: mass murder of the Jews of Europe on an unprecedented scale.

The case of the German ocean liner St. Louis is an infamous example of the worldwide indifference to the Nazi genocide in Europe. Jews in Key West saw the St. Louis up close, and poignantly felt the tragedy of its passengers. In May of 1939, nearly 1,000 Jews boarded the St. Louis in Hamburg, Germany, to sail to Havana. They were fleeing from Hitler’s Third Reich, and held the paperwork required by Cuban immigration authorities. Cuba had never been enthusiastic about accepting Jewish refugees, but a mix of humanitarian, political, and financial motivations had compelled them to continue to allow Jewish immigration. Now the anti-Semitism that fueled both Hitler’s rise and the American immigration quotas reached crisis proportions in Cuba as well.

Shortly before the St. Louis departed Hamburg, former Cuban President Grau San Martín organized a huge anti-Semitic demonstration in Havana. Nearly 40,000 people attended the rally, where San Martín’s spokesman urged them “to fight the Jews until the last one is driven out.” Caving to political pressure from these extremists, Cuban President Federico Laredo Brú voided the landing certificates that had recently been issued to Jewish refugees, including nearly all of those who were traveling aboard the St. Louis. Despised in Germany, where they had been stripped of basic rights, the Jewish passengers of the St. Louis were now refused entry by the one country that had seemed willing to grant them refuge.

When the St. Louis arrived in Havana after a two-week voyage, almost no one was permitted to leave the ship. As Jewish relief organizations in Cuba and the United States negotiated for the release of the passengers during the first week of June, the ship held anchor off the Cuban coast, then motored slowly north to Miami before turning south again and steaming toward Key West. Jews here, including Jack Einhorn, recall the heart-rending sight of the large ocean liner, later made famous as the “voyage of the damned.” The enormous ship idled offshore, almost motionless, as Jews in Key West read the news accounts of its ill-fated passengers.

By June of 1939, the immigration quota for German Jews had long since been filled (the waiting list was 10 years long), and port officials in Key West and Miami were powerless to accept the St. Louis passengers without an order from President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Although Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau Jr., the only Jew in Roosevelt’s cabinet, opened a secret channel with the U.S. Coast Guard to track the ship’s whereabouts, the St. Louis and its passengers were ultimately forced to return to Germany. More than half of them were eventually taken to extermination camps. Within a few years, Nazis had killed 254 of the passengers from the ship that had idled that day on the calm Atlantic waters within sight of Key West.

***

Excerpted from The Jews of Key West: Smugglers, Cigar Makers, and Revolutionaries (1823-1969), by Arlo Haskell. Copyright © Arlo Haskell 2017. Reprinted with permission.

Arlo Haskell is the author of, most recently,The Jews of Key West: Smugglers, Cigar Makers, and Revolutionaries (1823-1969).